Toby W. Clyman State University of New York at Albany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musorgsky's Boris Godunov

22 JANUARY 2019 Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov PROFESSOR MARINA FROLOVA-WALKER Today we are going to look at what is possibly the most famous of Russian operas – Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Its route to international celebrity is very clear – the great impresario Serge Diaghilev staged it in Paris in 1908, with the star bass Fyodor Chaliapin in the main role. The opera the Parisians saw would have taken Musorgsky by surprise. First, it was staged in a heavily reworked edition made by Rimsky-Korsakov after Musorgsky’s death, where only about 20% of the bars in the original were left unchanged. But that was still a modest affair compared to the steps Diaghilev took on his own initiative. The production had a Russian cast singing the opera in Russian, and Diaghilev was worried that the Parisians would lose patience with scenes that were more wordy, since they would follow none of it, so he decided simply to cut these scenes, even though this meant that some crucial turning points in the drama were lost altogether. He then reordered the remaining scenes to heighten contrasts, jumbling the chronology. In effect, the opera had become a series of striking tableaux rather than a drama with a coherent plot. But as pure spectacle, it was indeed impressive, with astonishing sets provided by the painter Golovin and with the excitement generated by Chaliapin as Boris. For all its shortcomings, it was this production that brought Musorgsky’s masterwork to the world’s attention. 1908, the year of the Paris production was nearly thirty years after Musorgsky’s death, and nearly and forty years after the opera was completed. -

Boris Godunov

Boris Godunov and Little Tragedies Alexander Pushkin Translated by Roger Clarke FE<NFIC; :C8JJ@:J ONEWORLD CLASSICS LTD London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.oneworldclassics.com Boris Godunov first published in Russian in 1831 The Mean-Spirited Knight first published in Russian in 1836 Mozart and Salieri first published in Russian in 1831 The Stone Guest first published in Russian in 1839 A Feast during the Plague first published in Russian in 1832 This translation first published by Oneworld Classics Limited in 2010 English translations, introductions, notes, extra material and appendices © Roger Clarke, 2010 Front cover image © Catriona Gray Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall ISBN: 978-1-84749-147-3 All the material in this volume is reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge the copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Boris Godunov 1 Introduction by Roger Clarke 3 Boris Godunov 9 Little Tragedies 105 Introduction by Roger Clarke 107 The Mean-Spirited Knight 109 Mozart and Salieri 131 The Stone Guest 143 A Feast during the Plague 181 Notes on Boris Godunov 193 Notes on Little Tragedies 224 Extra Material 241 Alexander Pushkin’s Life 243 Boris Godunov 251 Little Tragedies 262 Translator’s Note 280 Select Bibliography 282 Appendices 285 1. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, Ed

Rude and Barbarous Kingdom: Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, ed. Lloyd E. Berry and Robert O. Crummey, Madison, Milwaukee and London: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968. xxiii, 391 pp. $7.50. This attractively-presented volume is yet another instance of the work of publishers in making available in a more accessible form primary sources which it was hitherto necessary to seek among dusty collections of the Hakluyt Society publications. Here we have in a single volume accounts of the travels of Richard Chancellor, Anthony Jenkinson and Thomas Randolph, together with the better-known and more extensive narrative contained in Giles Fletcher's Of the Russe Commonwealth and Sir Jerome Horsey's Travels. The most entertaining component of this volume is certainly the series of descriptions culled from George Turberville's Tragicall Tales, all written to various friends in rhyming couplets. This was apparently the sixteenth-century equivalent of the picture postcard, through apparently Turberville was not having a wonderful time! English merchants evidently enjoyed high favour at the court of Ivan IV, but Horsey's account reflects the change of policy brought about by the accession to power of Boris Godunov. Although the English travellers were very astute observers, naturally there are many inaccuracies in their accounts. Horsey, for instance, mistook the Volkhov for the Volga, and most of these good Anglicans came away from Russia with weird ideas about the Orthodox Church. The editors have, by their introductions and footnotes, provided an invaluable service. However, in the introduction to the text of Chancellor's account it is stated that his observation of the practice of debt-bondage is interesting in that "the practice of bondage by loan contract did not reach its full development until the economic collapse at the end of the century and the civil wars that followed". -

The End of Boris. Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation

The end of Boris. ConTriBuTion To an aesTheTiCs of disorienTaTion by reuven Tsur The Emergence of the Opera–An Outline Boris Godunov was tsar of russia in the years 1598–1605. he came to power after fyodor, the son of ivan the terrible, died without heirs. Boris was fyodor's brother-in-law, and in fact, even during fyodor's life he was the omnipotent ruler of russia. ivan the Terrible had had his eldest son executed, whereas his youngest son, dmitri, had been murdered in unclear circumstances. in the 16–17th centuries, as well as among the 19th-century authors the prevalent view was that it was Boris who ordered dmitri's murder (some present-day historians believe that dmitri's murder too was ordered by ivan the Terrible). in time, two pretenders appeared, one after the other, who claimed the throne, purporting to be dmitri, saved miraculously. Boris' story got told in many versions, in history books and on the stage. Most recently, on 12 July 2005 The New York Times reported the 295-year-late premiere of the opera Boris Goudenow, or The Throne Attained Through Cunning, or Honor Joined Happily With Affection by the German Baroque composer Johann Mattheson. Boris' story prevailed in three genres: history, tragedy, and opera. in the nineteenth century, the three genres culminated in n. M. Karamzin's monumental History of the Russian State, in alexander Pushkin's tragedy Boris Godunov, and in Modest Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov. each later author in this list liberally drew upon his predecessors. in her erudite and brilliant 397 reuven tsur the end of boris book, Caryl emerson (1986) compared these three versions in a Pimen interprets as an expression of the latter's ambition. -

Boris Godunov

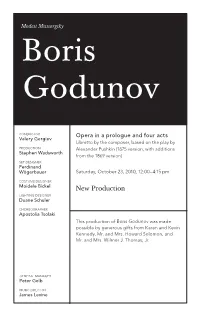

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Freedom from Violence and Lies Essays on Russian Poetry and Music by Simon Karlinsky

Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky simon Karlinsky, early 1970s Photograph by Joseph Zimbrolt Ars Rossica Series Editor — David M. Bethea (University of Wisconsin-Madison) Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky edited by robert P. Hughes, Thomas a. Koster, richard Taruskin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-158-6 On the cover: Heinrich Campendonk (1889–1957), Bayerische Landschaft mit Fuhrwerk (ca. 1918). Oil on panel. In Simon Karlinsky’s collection, 1946–2009. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

BORIS GODUNOV Modest Mussorgsky Prologue: at the Instigation of the Boyars, Headed by Shuisky, Russian Peasants Are Forced by P

BORIS GODUNOV Modest Mussorgsky Prologue: At the instigation of the Boyars, headed by Shuisky, Russian peasants are forced by police into demonstrating for Boris Godunov's ascension to the vacant throne of Russia. Shchelkalov, Secretary of the Duma (Council of Boyars), appears at the monastery doorway to announce that Boris still refuses and that Russia is doomed. A procession of pilgrims passes, praying to God for help. Amidst cheering crowds, the great bells of Moscow herald the coronation of Boris. As the procession leaves the cathedral, Boris appears in triumph. Haunted by a strange foreboding, he prays for God's blessing. Addressing his people, he invites them all to the feast, as the crowd resumes rejoicing. ACT I: The old monk Pimen is finishing a history of Russia. Young Grigory, a novice, awakes and describes to Pimen his nightmare in which he climbed a lofty tower and viewed the swarming multitude of Muscovites below who mocked him until he stumbled and fell. Pimen tells Grigory that fasting and prayer bring peace of mind, and compares the quiet solitude of the cloister to the outside world of sin and idle pleasure. Grigory questions Pimen about the dead Tsarevich Dimitri, legal heir to the Russian throne; Pimen recounts how Boris ordered the boy's murder. Left alone, Grigory condemns Boris and his crime and decides to leave the cloister. Three guests interrupt the innkeeper's ballad: two drunken monks-Varlaam and Missail-and the disguised Grigory, who is being pursued by the police for escaping from the monastery. Now considering it his mission to expose Boris, Grigory is attempting flight to Lithuania, where he will assemble forces and, proclaiming himself the Tsarevich Dimitri, claim the Russian throne. -

'Pushkin Was a Live Volcano . . .'

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 8, Number 3, Fall 1999 ‘Pushkin Was a Live Volcano...’ The Poet, As Seen by His Contemporaries by E.S. Lebedeva Pushkin was a live volcano, whose collaboration, chance meetings on inner life burst from him like the post roads, or in some Cos- a column of fire. sack settlement, or on the Geor- —F. Glinka (I, 245)1 gian Military Highway. People of different levels of culture gave Poetry is the exclusive passion of those testimony about him, and there is few, who are born poets. a great range of variety in how —A.S. Pushkin they perceived the personality of the poet: from tender solicitude at ushkin lived his life in a big the sight of a missing button on and noisy crowd—not in his jacket, to amazement at the Pisolation, but surrounded by scope of the phenomenon that many people who had the opportu- was Pushkin. nity to see him. We can hear the All social layers are represent- chorus of his contemporaries, with ed on the list of people who have its great range of voices, in their said what they had to say about reminiscences about him. the poet—from the Emperor to These memoirs have a certain the serf, from the fashionable for- peculiar feature. The people closest tune-teller to the old Cossack to the poet found it difficult to Manuscript sketch, 1820, self-portrait (lower left) woman, who remembered speak, and they did not do so right with members of the Rayevsky family. -

Review of Pushkinskaia Entsiklopediia “Mikhailovskoe”

This document is an electronic post-print of a book review published in Slavic & East European Information Resources: Giullian, Jon. Book Review. Pushkinskaia Entsiklopediia “Mikhailovskoe” (Pushkin Encyclopedia “Mikhailovskoe”). Edited by e. B. Egorova. Mikhailovskoe: Gos. Muzei-zapovednik A.S. Pushkina „Mikhailovskoe,” 2003. v. 1. Slavic & East European Information Resources, 7.4 (2006): 146-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J167v07n04_12. Typographical errors have been corrected in this version. NOTE: Cites to this article should be made to the version published in SEEIR. Egorova, E. B, ed. Pushkinskaia Entsiklopediia “Mikhailovskoe” (Pushkin Encyclopedia “Mikhailovskoe”). Mikhailovskoe: Gos. Muzei-zapovednik A.S. Pushkina „Mikhailovskoe,” 2003. v. 1. 447p. ISBN: 5945950269. Jon C. Giullian1 The encyclopedia represents the collaborative work of academicians and associates of the State Memorial Museum-Preserve of A. S. Pushkin, “Mikhailovskoye” (Госурдарственный мемориальный музей-заповедник А.С. Пушкина «Михайловское»). The official name of the museum preserve in English is the State Memorial Historical-Literary and Natural-Landscape Museum Preserve of A.S. Pushkin “Mikhailovskoye” (Государственный мемориальный историко-литературный и природно-ландшафтный музей-заповедник А.С.Пушкина "Михайловское"). For the sake of ease and brevity, the museum will heretofore be referred to as the “Pushkin museum-preserve.” 1 Jon C. Giullian, MA, MLS, is Slavic Librarian, University of Kansas, 519 Watson Library, 1425 Jayhawk Blvd., Lawrence, KS 66045 (E-mail: [email protected]). Review: Pushkinskaia Entsiklopediia “Mikhailovskoe,” Page 2 of 6 Paraphrasing the editor’s summary, the work sets out to be a type of systematic guide to information about the realities of A. S. Pushkin’s life in the Pskov region. -

All the Same the Words Don't Go Away

All the Same The Words Dont Go Away Essays on Authors, Heroes, Aesthetics, and Stage Adaptations from the Russian Tradition Caryl Emerson Caryl Emerson STUDIES IN RUSSIAN AND SLAVIC ARS ROSSIKA LITERATURES, CULTURES AND HISTORY Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman Series Editor: David Bethea (Stanford Universtity) (University of Wisconsin — Madison and Oxford University) All the Same The Words Dont Go Away Essays on Authors, Heroes, Aesthetics, and Stage Adaptations from the Russian Tradition Caryl Emerson Caryl Emerson Boston 2011 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Emerson, Caryl. All the same the words don’t go away : essays on authors, heroes, aesthetics, and stage adaptations from the Russian tradition / Caryl Emerson. p. cm. -- (Studies in Russian and Slavic literatures, cultures and history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-934843-81-9 (hardback) 1. Russian literature--History and criticism. 2. Russian literature--Adaptations--History and criticism. I. Title. PG2951.E46 2011 891.709--dc22 2010047494 Copyright © 2011 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved Effective May 23, 2016, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. ISBN 978-1-934843-81-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-618111-28-9 (electronic) Book design by Ivan Grave On the cover: Saskia Ozols Eubanks, St. Isaac’s Cathedral After the Storm. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 7131

ALEXANDER PUSHKIN THE QUEEN OE SPADES AND SELECTED WORKS Translated from the Russian by Anthony Briggs Pushkin Press LONDON The Queen of Spades [Pikovaya dama) CONTENTS originally published in Russian in 1834 The Stationmaster {Stanisionnyy smotritel’) originally published in Introduction Russian in The Tales of the Late Ivan Petrovich Belkin {Povestipokoynogo Ivana Petrovicha Belkina) in 1830 The Queen of Spades The Stationmaster All English language translations in this volume Extract from the Blank-Verse © A.D.P. Briggs, 2012 Tragedy Boris Godunov This edition first published in 2012 by Mozart and Salieri Pushkin Press The Bronze Horseman 71-75 Shelton Street Tsar Nikita and His Forty Daughters . London WC2H9JQ, Extract from Tevgeny Onegin The Prophet ISBN 978 1 908968 03 6 To Anna Kern All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Winter Evening reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any The Upas Tree form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, Man Found Drowned recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing ‘Winter. What Shall We Do?’ from Pushkin Press ‘When I Stroll Down a Busy Street’ ‘Oh, I Have Loved You’ Frontispiece: Portrait of Alexander Pushkin ‘No, Not for Me the Stormiest by Vasili Andreevich Tropinin, © State Russian Museum, Pleasures of the Senses’ St Petersburg/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library ‘When I Reach Over to Enfold You’ Set in 10 on 13 Monotype Baskerville ‘The Time Has Gome, Dear Friend’ by Tetragon, London Autumn (A Fragment) and printed in Great Britain on Munken Premium White 90 gsm Elegy by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall Remembrance ‘I Have My Monument’ www.pushkinpress.com Ignore them, please.