RIMYI Certification Course Guidlines Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prescribing Yoga to Supplement and Support Psychotherapy

12350-11_CH10-rev.qxd 1/11/11 11:55 AM Page 251 10 PRESCRIBING YOGA TO SUPPLEMENT AND SUPPORT PSYCHOTHERAPY VINCENT G. VALENTE AND ANTONIO MAROTTA As the flame of light in a windless place remains tranquil and free from agitation, likewise, the heart of the seeker of Self-Consciousness, attuned in Yoga, remains free from restlessness and tranquil. —The Bhagavad Gita The philosophy of yoga has been used for millennia to experience, examine, and explain the intricacies of the mind and the essence of the human psyche. The sage Patanjali, who compiled and codified the yoga teachings up to his time (500–200 BCE) in his epic work Yoga Darsana, defined yoga as a method used to still the fluctuations of the mind to reach the central reality of the true self (Iyengar, 1966). Patanjali’s teachings encour- age an intentional lifestyle of moderation and harmony by offering guidelines that involve moral and ethical standards of living, postural and breathing exercises, and various meditative modalities all used to cultivate spiritual growth and the evolution of consciousness. In the modern era, the ancient yoga philosophy has been revitalized and applied to enrich the quality of everyday life and has more recently been applied as a therapeutic intervention to bring relief to those experiencing Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for further distribution. physical and mental afflictions. For example, empirical research has demon- strated the benefits of yogic interventions in the treatment of depression and anxiety (Khumar, Kaur, & Kaur, 1993; Shapiro et al., 2007; Vinod, Vinod, & Khire, 1991; Woolery, Myers, Sternlieb, & Zeltzer, 2004), schizophrenia (Duraiswamy, Thirthalli, Nagendra, & Gangadhar, 2007), and alcohol depen- dence (Raina, Chakraborty, Basit, Samarth, & Singh, 2001). -

Yoga Federation of India (Regd

YOGA FEDERATION OF INDIA (REGD. UNDER THE SOCIETIES REGISTRATION ACT. XXI OF 1860 REGD. NO.1195 DATED 14.02.90) RECOGNIZED BY INDIAN OLYMPIC ASSOCIATION - OCTOBER, 1998 TO FEBRUARY, 2011 Affiliated to Asian Yoga Federation, International Yoga Sports Federation & International Yoga Federation REGD. OFFICE: FLAT NO.501, GHS-93, SECTOR-20, PANCHKULA- 134116 (HARYANA), INDIA e-mail:[email protected], Mobile No.+91-94174-14741, Website:- www.yogafederationofindia.com SYLLABUS AND GUIDELINES FOR NATIONAL/ZONAL/STATE/DISTRICT YOGASANA COMPETITION SENIOR GROUP-A (18-21 YEARS MEN AND WOMEN) 1. TRIVIKRAMASANA 2. PURNA CHAKRASANA 3. UTHITA PASCHIMOTTASANA 4. KOUNDINYASANA 5. PARIVARTITA PARSVAKONASANA 1. TRIVIKRAMASANA 6. OMKARASANA 1. Leg on the ground to be straight. 7. PURNA MATSYENDRASANA 2. Gripping of toe of other leg with palm. 8. KARAN PITTHASANA 3. The stretched leg should be straight. 4. Both elbows in alignment, gaze in 9. PURNA DHANURASANA front. 10. SIRSHASANA 2. PURNA CHAKRASANA 3. UTTHITA PASCHIMOTTANASANA 4. KOUNDINYASANA 1. Balance on Buttocks. 1. Gap in two legs approx ½ feet. 1. Both legs in straight line. 2. Both Legs straight with toes pointing 2. Both palms on the ground with 2. Gripping of ankles with hands. upward. fingers & thumb together. 3. Toes parallel to each other. 3. Palms holding the heels with heels and 3. Both forearms parallel to each other, toes together. perpendicular to the ground. 4. Head placed in between arms with 4. Back maximum stretched with abdomen, 4. Back maximum stretched, parallel to chest and forehead touching the legs. ear touching the arms (biceps). the ground, Gaze forward. 4. -

Levels 8 & 9 – Advanced & Master

TEACHER TRAINING with Master Teacher Nicky Knoff CAIRNS, Queensland Levels 8 & 9 – Advanced & Master Monday 2nd – Friday 27th August 2021 5:45 am - 4:00 pm Non-residential VENUE The Yoga School Suite 14, 159-161 Pease St (Piccones Village) Edge Hill, CAIRNS PO Box 975, Edge Hill, 4870, QLD CONTACT James E. Bryan (ERYT500) - Program Director Mobile 0415 362 534 Email: [email protected] Website: www.knoffyoga.com Levels 8 & 9 – Advanced & Master THE HISTORY In 1994, Nicky Knoff and James Bryan took a sabbatical to the Mount Quincan Crater Retreat, just outside of Yungaburra in the Atherton Tablelands behind Cairns, Far North Queensland, Australia. The goal was to create a comprehensive and complete new program, which incorporated the anatomical alignment and progression of Asanas in Iyengar Yoga, and combine it with the energetic aspects of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga viz. Bandhas, Drishti, Ujjayi Pranayama and Vinyasa. We learned in Iyengar Yoga how to progressively practice postures. For example with Backbends, you perform an easy pose to warm up, a stronger pose to work more deeply, and then the strongest pose of the session – challenging yourself in a safe and methodical manner. This safe and methodical approach – carefully easing deeper into postures, was not a concept we found in Ashtanga Yoga. In fact, as we progressed through the Series (1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th) we could not discern any logical sequencing. It was as if someone had written down the various yoga poses on pieces of paper, thrown them into a hat, and pulled them out at random. With traditional Ashtanga, you only progress if you can do the postures in the Series order and if not, you stay stuck on the particular challenging pose, until you can. -

Ashtanga Yoga As Taught by Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Copyright ©2000 by Larry Schultz

y Ashtanga Yoga as taught by Shri K. Pattabhi Jois y Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Do your practice and all is coming (Guruji) To my guru and my inspiration I dedicate this book. Larry Schultz San Francisco, Califórnia, 1999 Ashtanga Ashtanga Yoga as taught by shri k. pattabhi jois Copyright ©2000 By Larry Schultz All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reprinted without the written permission of the author. Published by Nauli Press San Francisco, CA Cover and graphic design: Maurício Wolff graphics by: Maurício Wolff & Karin Heuser Photos by: Ro Reitz, Camila Reitz Asanas: Pedro Kupfer, Karin Heuser, Larry Schultz y I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead. His faithful support and teachings helped make this manual possible. forward wenty years ago Ashtanga yoga was very much a fringe the past 5,000 years Ashtanga yoga has existed as an oral tradition, activity. Our small, dedicated group of students in so when beginning students asked for a practice guide we would TEncinitas, California were mostly young, hippie types hand them a piece of paper with stick figures of the first series with little money and few material possessions. We did have one postures. Larry gave Bob Weir such a sheet of paper a couple of precious thing – Ashtanga practice, which we all knew was very years ago, to which Bob responded, “You’ve got to be kidding. I powerful and deeply transformative. Practicing together created a need a manual.” unique and magical bond, a real sense of family. -

Level 1 Asanas

LEVEL 1 ASANAS Standing Poses Tadasana (Mountain Pose) Vrksasana (Tree Pose) Virabhadrasana II (Warrior Pose 2) Utthita Parsvakonasana (Extended Lateral Flank Stretch) Utthita Trikonasana (Extended Triangle Pose) Virabhadrasasana (Warrior Pose 1) Uttanasana (Standing Forward Bend) Prasarita Padottanasana (Extended Leg Stretch) Parsvottanasana (Intense Side Stretch) Seated Poses Vajasana (Thunderbolt Pose) Virasana (Hero Pose) Sukhasana (Comfortable Seated Pose) Dandasana (Staff Pose) Upavista Konasana (Seated Angle Pose) Baddha Konasana (Bound Angle Pose) Forward Bends Paschimottanasa (Intense Seated Back Stretch) Supta Padangusthasana (Reclining Leg Stretch) Twists Sukhasana Twist (Easy Cross Leg Twists) Bharadvasjasana (Chair Twist) Bharadvasjasana I (Seated Twist) Jathara Parivartanasana ( Supine Adominal Twists) Crocodile Twists Maricyasana III LEVEL 1 ASANAS Hip Openers Supta Padangusthasana II (Reclining Leg Stretch 2) Judith’s Hip Opener Gomukhasana (Face of the Cow Pose) Arm Work Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward Facing Dog Pose) Plank Pose Chaturanga Dandasana (Four Point Staff Pose) Half Handstand Simple Backbends Passive Chest Opener (Lie over a rolled up blanket) Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Bridge Pose) Ustrasana (Camel Pose) Restorative Poses Supported Uttanasana (Forward bend with head on block - or buttocks on wall) Supported Adho Mukha Svanesana (Dog Pose with head support) Supported Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Bridge Pose with block under sacrum) Supta Virasana (Reclining Bound Pose) Supta Baddha Konasana (Reclining Bound Angle Pose) Viparita Karani (Two blankets under hips- legs up wall) Savasana (Corpse Pose). -

COMMENT TROUVER Les POSTURES Dans Les LIVRES IYENGAR ?

COMMENT TROUVER les POSTURES dans les LIVRES IYENGAR ? - « Lumière sur le Yoga » de B.K.S Iyengar (édition Buchet Chastel) = LSY et sa version format poche « Bible du Yoga » (édition J’ai Lu) = Bible - « Yoga, Joyau de la Femme » (édition Buchet Chastel) = Yoga Femme et « Cour d’Initiation» de Geeta Iyengar (édition AFYI) = Cours Initiation Noms des postures n° n° n° n° n° n° POSTURE PAGE PAGE POSTURE PAGE PAGE LSY- Bible LSY Bible Yoga, Yoga, Cours B.K.S. B.K.S. B.K.S. Femme Femme Initiation Iyengar Iyengar Iyengar Geeta Geeta Geeta Adho Mukha Svanasana 33 85 130 14 123 49 Adho Mukha Vrksasana 132 213 310 Akarna Dhanurasana 73 133 199 Anantasana 109 183 269 Anuloma Pranayama 214 340 487 Ardha Baddha Padma Paschimottanasana 61 117 177 17 129 Ardha Baddha Padmottanasana 22 74 115 Ardha Chandrasana 10 60 95 8 112 32 Ardha Halasana 83 Ardha Matsyendrasana I 116 191 281 67 228 Ardha Matsyendrasana II 120 200 292 Ardha Matsyendrasana III 121 201 294 Ardha Navasana 36 87 133 Ashtavakrasana 123 204 299 Baddha Hasta Sirsasana 78 146 218 Baddha Konasana 44 99 151 23 139 54 Baddha Konasana en Sirsasana 44 179 Baddha Padmasana 55 110 168 35 161 Bakasana 152 233 339 Bhairavasana 139 220 321 Brahmari Pranayama 208 335 478 Bhastrika Pranayama 206 334 476 Bhekasana 43 98 149 Bharadvajasana I 112 186 274 64 223 72 Bharadvajasana II 113 187 275 65 226 74 Bharadvajasana + chaise 75 Bhujangasana I 31 83 128 74 251 Bhujangasana II 189 292 416 Bhujapidasana 126 207 303 Buddhasana 137 218 319 Chakorasana 141 221 322 1 Noms des postures n° n° n° n° n° n° POSTURE PAGE PAGE POSTURE PAGE PAGE LSY- Bible LSY Bible Yoga, Yoga, Cours B.K.S. -

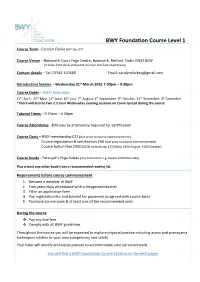

BWY Foundation Course Level 1

BWY Foundation Course Level 1 Course Tutor - Carolyn Clarke BWY Dip: DCT Course Venue – Babworth Court Yoga Centre, Babworth, Retford, Notts DN22 8EW (2 miles from A1 & accessible on main line East coast trains) Contact details – Tel: 07561 107660 Email: [email protected] Introductory Session – Wednesday 31st March 2021 7.00pm – 9.30pm Course Dates – 2021- Saturdays 17th April: 22nd May: 12th June: 10th July: 7th August: 4th September: 9th October: 13th November: 4th December *There will also be two 2.5 hour Wednesday evening sessions on Zoom spread during the course Tutorial Times – 9.45am – 4.30pm Course Attendance - 80% course attendance required for certification Course Costs – BWY membership £37 (due prior to course commencement) Course registration & certification £60 (due prior to course commencement) Course tuition fees £500 (£100 on booking: £150 May: £150 August: £100 October) Course books - Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (any translation e.g. Swami Satchidananda) Plus a least one other book from a recommended reading list Requirements before course commencement 1. Become a member of BWY 2. Two years class attendance with a recognised teacher 3. Fill in an application form 4. Pay registration fee and tutorial fee payments as agreed with course tutor 5. Purchase course book & at least one of the recommended ones During the course v Pay any due fees v Comply with all BWY guidelines Throughout the course you will be expected to explore physical practice including asana and pranayama techniques relative to your own competency and safety. Your tutor will modify and adjust posture to accommodate your personal needs. You will find a BWY Foundation Course Syllabus on the next pages BRITISH WHEEL OF YOGA SYLLABUS - FOUNDATION COURSE 1 The British Wheel of Yoga Foundation Course 1 focuses on basic practical techniques and personal development taught in the context of the philosophy that underpins Yoga. -

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

Yoga Anatomy / Leslie Kaminoff, Amy Matthews ; Illustrated by Sharon Ellis

Y O G A ANATOMY second edItIon leslie kaminoff amy matthews Illustrated by sharon ellis Human kinetics Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaminoff, Leslie, 1958- Yoga anatomy / Leslie Kaminoff, Amy Matthews ; Illustrated by Sharon Ellis. -- 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-4504-0024-4 (soft cover) ISBN-10: 1-4504-0024-8 (soft cover) 1. Hatha yoga. 2. Human anatomy. I. Matthews, Amy. II. Title. RA781.7.K356 2011 613.7’046--dc23 2011027333 ISBN-10: 1-4504-0024-8 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-4504-0024-4 (print) Copyright © 2012, 2007 by The Breathe Trust All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, and recording, and in any information storage and retrieval system, is forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. This publication is written and published to provide accurate and authoritative information relevant to the subject matter presented. It is published and sold with the understanding that the author and publisher are not engaged in rendering legal, medical, or other professional services by reason of their authorship or publication of this work. If medical or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. The web addresses cited in this text were current as of August 2011, unless otherwise noted. Managing Editor: Laura Podeschi; Assistant Editors: Claire Marty and Tyler Wolpert; Copyeditor: Joanna Hatzopoulos Portman; Graphic Designer: Joe Buck; Graphic Artist: Tara Welsch; Original Cover Designer and Photographer (for illustration references): Lydia Mann; Photo Production Manager: Jason Allen; Art Manager: Kelly Hendren; Associate Art Manager: Alan L. -

Exercise Yogasan

EXERCISE YOGASAN YOGA The word meaning of “Yoga” is an intimate union of human soul with God. Yoga is an art and takes into purview the mind, the body and the soul of the man in its aim of reaching Divinity. The body must be purified and strengthened through Ashtanga Yogas-Yama, Niyama, Asanas and Pranayama. The mind must be cleansed from all gross through Prathyaharam, Dharana, Dhyanam and Samadhi. Thus, the soul should turn inwards if a man should become a yogic adept. Knowledge purifies the mind and surrender takes the soul towards God. TYPE OF ASANAS The asanas are poses mainly for health and strength. There are innumerable asanas, but not all of them are really necessary, I shall deal with only such asanas as are useful in curing ailments and maintaining good health. ARDHA CHAKRSANA (HALF WHEEL POSTURE) This posture resembles half wheel in final position, so it’s called Ardha Chakrasana or half wheel posture. TADASANA (PALM TREE POSE) In Sanskrit ‘Tada’ means palm tree. In the final position of this posture, the body is steady like a Palm tree, so this posture called as ‘Tadasana’. BHUJANGAASANA The final position of this posture emulates the action of cobra raising itself just prior to striking at its prey, so it’s called cobra posture or Bhujangasan. PADMASANA ‘Padma’ means lotus, the final position of this posture looks like lotus, so it is called Padmasana. It is an ancient asana in yoga and is widely used for meditation. DHANURASANA (BOW POSTURE) Dhanur means ‘bow’, in the final position of this posture the body resembles a bow, so this posture called Dhanurasana or Bow posture. -

Yoga Federation of India ( Regd

YOGA FEDERATION OF INDIA ( REGD. UNDER THE SOCIETIES REGISTRATION ACT. XXI OF 1860 REGD. NO.1195 DATED 14.02.90) RECOGNIZED BY INDIAN OLYMPIC ASSOCIATION - OCTOBER, 1998 TO FEBRUARY, 2011 Affiliated to Asian Yoga Federation, International Yoga Sports Federation & International Yoga Federation REGD. OFFICE: FLAT NO.501, GHS-93, SECTOR-20, PANCHKULA- 134116 (HARYANA), INDIA e-mail:[email protected], Mobile No.+91-94174-14741, Website:- www.yogafederationofindia.com SYLLABUS AND GUIDELINES FOR NATIONAL/ZONAL/STATE/DISTRICT YOGASANA COMPETITION SUB JUNIOR GROUP–A (8-1110 YEARS, BOYS & GIRLS) 1. VRIKSHASANA 2. PADAHASTASANA 3. SASANGASANA 4. USHTRASANA 5. AKARNA DHANURASANA 6. GARABHASANA 1. VRIKSHASANA 7. EKA PADA SIKANDHASANA 1. Back maximum stretched. 2. Arms touching the ear. 8. CHAKRASANA 3. Both hands folded above the 9. SARVANGASANA shoulders. 10. DHANURASANA 4. Gaze in front. 2. PADAHASTASANA 3. SASANGASANA 4. USHTRASANA 1. Hands on the side of feet 1. Thighs perpendicular to the ground 1. Thighs perpendicular to the ground 2. Legs should be straight 2. Forehead touching knees 2. Palms on the heels 3. Back maximum stretched 3. Palms on the heels from the side 3. Knees, heels and toes together 4. Chest & forehead touching the legs 4. Toes, heels and knees together 4. Ankles touching the ground 5. AKARNA DHANURASANA 6. GARABHASANA 7. EKA PADA SIKANDHASANA 1. One Leg stretch with toe pointing upwards, gripping of toe with thumb and 1. Both arms in between thigh and calf. 1. Back, neck and head to be maximum index finger. 2. Ears to be covered by palms. straight. 2. Gripping of toe of other leg with thumb, 2. -

Yoga Asana Pictures

! ! Padmasana – Lotus Pose Sukhasana – Easy Pose ! ! Ardha Padmasana – Half Lotus Pose Siddhasana – Sage or Accomplished Pose ! ! Vajrasana –Thunderbolt Pose Virasana – Hero Pose ! ! Supta Padangusthasana – Reclining Big Toe Pose Parsva supta padangusthasana – Side Reclining Big Toe Pose ! ! Parrivrtta supta padangusthasana – Twisting Reclining Big Toe Pose Jathara parivartanasana – Stomach Turning Pose ! ! Savasana – Corpse Pose Supta virasana – Reclining Hero Pose ! ! ! Tadasana – Mountain Pose Urdhva Hastasana – Upward Hands Pose Uttanasana – Intense Stretch or Standing Forward Fold ! ! Vanarasana – Lunge or Monkey Pose Adho mukha dandasana – Downward Facing Staff Pose ! ! Ashtanga namaskar – 8 Limbs Touching the Earth Chaturanga dandasana – Four Limb Staff Pose ! ! Bhujangasana – Cobra Pose Urdvha mukha svanasana – Upward Facing Dog Pose ! ! Adho mukha svanasana - Downward Facing Dog Pose Trikonasana – Triangle Pose ! ! Virabhadrasana II – Warrior II Pose Utthita parsvakonasana – Extended Lateral Angle (Side Flank) ! ! Parivrtta parsvakonasana – Twisting Extended Lateral Angle (Side Flank) Ardha chandrasana – Half Moon Pose ! ! ! Vrksasana – Tree Pose Virabhadrasana I – Warrior I Pose Virabhadrasana III – Warrior III Pose ! ! Prasarita Paddottasana – Expanded/Spread/Extended Foot Intense Stretch Pose Parsvottanasana – Side Intense Stretch Pose ! ! ! Utkatasana– Powerful/Fierce Pose or Chair Pose Uttitha hasta padangustasana – Extended Hand Big Toe Pose Natarajasana – Dancer’s Pose ! ! Parivrtta trikonasana- Twisting Triangle Pose Eka