Who's Afraid of Human Rights? the Judge's Dilemma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnic Diversity in Politics and Public Life

BRIEFING PAPER CBP 01156, 22 October 2020 By Elise Uberoi and Ethnic diversity in politics Rebecca Lees and public life Contents: 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 2. Parliament 3. The Government and Cabinet 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 5. Public sector organisations www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Ethnic diversity in politics and public life Contents Summary 3 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 6 1.1 Categorising ethnicity 6 1.2 The population of the United Kingdom 7 2. Parliament 8 2.1 The House of Commons 8 Since the 1980s 9 Ethnic minority women in the House of Commons 13 2.2 The House of Lords 14 2.3 International comparisons 16 3. The Government and Cabinet 17 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 19 4.1 Devolved legislatures 19 4.2 Local government and the Greater London Authority 19 5. Public sector organisations 21 5.1 Armed forces 21 5.2 Civil Service 23 5.3 National Health Service 24 5.4 Police 26 5.4 Justice 27 5.5 Prison officers 28 5.6 Teachers 29 5.7 Fire and Rescue Service 30 5.8 Social workers 31 5.9 Ministerial and public appointments 33 Annex 1: Standard ethnic classifications used in the UK 34 Cover page image copyright UK Youth Parliament 2015 by UK Parliament. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 / image cropped 3 Commons Library Briefing, 22 October 2020 Summary This report focuses on the proportion of people from ethnic minority backgrounds in a range of public positions across the UK. -

The Making of 100 Great Black Britons Patrick Vernon

The Making of 100 Great Black Britons Patrick Vernon OBE BBC Great Britons Campaign 2001-2002 100 Great Black Britons campaign 2003-2004 Results and Impact of Campaign 2004-2019 2013 Mary Seacole vs Michael Gove • 16 Years new achievers • More historical research and publications • Windrush scandal and Brexit raising issues of identity of britishness and Black British Identity • Opportunity to publish book and board game as education resource and family learning 2019 Campaign Nominate www.100greatblackbritons.co.uk 2020 100 Great Black Britons Dr Maggie Aderin- Pocock Space scientist, science communicator and presenter of the BBC’s The Sky at Night. She completed a PhD in the Department of Mechanical Engineering in 1994, after an undergraduate degree in Physics also at Imperial. She is Managing Director of Science Innovation Ltd, through which she organises public engagement activities which show school children and adults the wonders of space. DAME ELIZABETH ANIONWU Nurse and transform care for people with sickle cell disease Dr Aggrey Burke British retired psychiatrist and academic who spent the majority of his medical career at St George's Hospital in London, UK, specialising in transcultural psychiatry and writing literature on changing attitudes towards black people and mental health. He has carried out extensive research on racism and mental illness and is the first black consultant psychiatrist appointed by Britain's National Health Service (NHS). • Alongside careers in research, science, technology and Sir Geoff teaching, brewing science pioneer Professor Sir Geoff Palmer has contributed greatly to civil society and has a keen interest Palmer in Scottish-Caribbean historical connections. -

Teachers. Understanding Slavery Initiative

Understanding Slavery Initiative Teachers Primary Resources Please visit the Primary Teachers page for full details on the resources available to assist teaching about transatlantic slavery at a Primary level. Teaching Slavery FAQs The FAQs offer guidance to those who wish to engage younger children with the history of transatlantic slavery and its legacies Breakfast Exploring where your breakfast comes from… EYFS KS1 KS2 My Name Where does your name come from? EYFS KS1 KS2 Treasure What does Treasure mean to you? EYFS KS1 KS2 Carnival Learn about, plan and stage your own carnival… EYFS KS1 KS2 Secondary Resources Please visit the Secondary Teachers page for full details on the resources available to assist teaching about transatlantic slavery at a Secondary level. Activities A selection of theme related activities Books Books A selection of added reading materials PDFs All content available to download as PDFs Sound files Sound files including accounts by Olaudah Equiano USI Resources Approach to the history and legacies of transatlantic slavery Video Training Using artefacts to teach Transatlantic slavery Maps A selection of maps Timeline A timeline Case Studies Case Studies Sensitivities Teaching Transatlantic Slavery in a thoughtful and sensitive way Use of Language How best to use language associated with the history Glossary of terms Historical and contemporary terms and their meanings Help from the historians Help from the historians Other Resources Third party external resources Third party external Collections resources The Atlantic -

Black History Month with a Programme of Free Events and Tours

September 2015 IWM marks Black History Month with a programme of Free Events and Tours Visitors to the Imperial War Museums this October can discover more about the role of the black community at home and on the fighting front, from the First World War through to the present day. A special screening will be held at IWM London (Sun 25 Oct) of two documentary films held in our collections telling the stories of African and Caribbean men who fought in the Second World War. Each will be introduced by their Directors. Discover the story of Eddie Noble a Jamaican born London resident who served in the RAF in the Second World War – who inspired Andrea Levy’s best-seller Small Island. Find out about the 100,000 African soldiers who fought in Burma and their story of courage and survival in the documentary Burma Boy (1 – 2.30pm). Visitors can see our new display at IWM North −Mixing It: The Changing Faces of Wartime Britain and find out about Peter Thomas, the first Nigerian pilot to serve with the RAF. Join us for a series of interactive talks at IWM London where expert historians will reveal through the moving personal accounts held in IWM’s collections what it was like for black servicemen to serve during the First and Second World Wars. Historian Stephen Bourne’s talk Black Poppies (31 October, 1pm) will be accompanied by a free display telling stories of Britain’s Black Community during the First World War. Hear the voices and stories of those who served in the West India Regiment in Palestine during the First World War in historian Tony Warner’s talk (1 November, 11.30am) and in the afternoon (2.30pm) Warner will reveal the experiences of black pilots and troops who fought in the Second World War. -

Hidden Stories of the Slave Trade

Hidden Stories of the Slave Trade Through the initiatives of per- that died of a consumption; and being dead, he sistent campaigners and the estab- caused him to be dried in an Oven, and lies there lishment of websites such as 100 entire in a box'. Great Black Britons and The Black Abolitionists made use of the trade in children to Presence in Britain, the names of highlight the evils of slavery. The historical figures such as Mary Society for the Purpose of Seacole, John Archer and William Effecting the Abolition of the Cuffay are becoming more familiar African Slave Trade gathered in the UK's schools. In addition, evidence such as the case of commemoration of the bicentenary George Dale who was kidnapped and transported of the act to abolish the trade in from Africa aged about 11. He arrived in Scotland slaves, has brought to the forefront figures such as after working as a plantation cook and then as a Ignatius Sancho, Ottobah Cuguano and Mary crewman on a fighting ship. Prince, highlighting their contribution to the move- ment to abolish the trade. Loyal and not so loyal service A little digging, though, uncovers a wealth of Two Black servants accompanied their master on other, hidden stories - tales of hypocrisy, appalling Captain Cook's first voyage round the world in cruelty, guile, bravery and sheer determination that 1768. Together with a can have relevance to geography, citizenship, reli- white seaman, they gious education and law as well as history. climbed a mountain to gather rare plants for To have and to own scientific purposes. -

Mack, S. 2010.Pdf

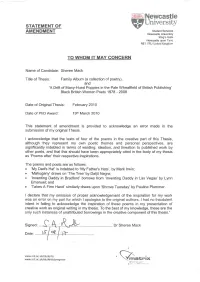

Family Album (a collection of poetry), and lA Drift of Many-Hued Poppies in the Pale Wheatfield of British Publishing': Black British Women Poets 1978 - 2008 Sheree Mack A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Newcastle University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2010 NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ---------------------------- 208 30279 h Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Family Album, a collection of poetry 1 The Voice of the Draft 49 Dissertation: 'A Drift of Many-Hued Poppies in the Pale Wheatfield of 54 British Publishing': Black British Women Poets 1978 - 2008 Introduction 55 Linking Piece: 'she tries her tongue' 1 72 Chapter One: Introducing Black Women Writers to Britain 76 Linking Piece: 'she tries her tongue' 2 102 Chapter Two: Black Women Insist On Their Own Space 105 Linking Piece: 'she tries her tongue' 3 148 Chapter Three: Medusa Black, Red, White and Blue 151 The Voice of the Tradition 183 Chapter Four: Conclusion 189 Linking Piece: 'she tries her tongue' 4 194 Select Bibliography 197 Abstract The thesis comprises a collection of poems, a dissertation and a series of linking pieces. Family Album is a portfolio of poems concerning the themes of genealogy, history and family. It also explores the use of devices such as voice, the visual, the body and place as an exploration of identity. Family Album includes family elegies, narrative poems and commissioned work. The dissertation represents the first study of length about black women's poetry in Britain. Dealing with a historical tradition dating back to the eighteenth century, this thesis focuses on a recent selection of black women poets since the late 1970s. -

How the Caribbean Intellectuals 1777 1788 1800’S 1845 1869 1887 1901 1902 1911 1915 1942

How the Caribbean Intellectuals 1777 1788 1800’s 1845 1869 1887 1901 1902 1911 1915 1942 Maria Jones JJ Thomas Philip Douglin Sylvester Williams Marcus Mosiah Garvey CLR James George Padmore Eric Williams Walter Rodney (c.1777) (c.1850) (1845-1902) (1869-1911) (1887-1940) (1901-1989) (1902-1959) (1911- ) (1942-1980) Born in West Africa Maria Jones Writer on Intellectual Pioneer Pan African Pioneer Father of West Indian Literary Giant Father of Pan African Politician and Theorist of book Maria Jones: her history in Emancipation Nationalism Independence Polemicist Underdevelopment Caribbean In his varied life Philip Douglin Born in Trinidad, Sylvester Born in Trinidad James was a Africa and in the West Indies may qualified for Holy Orders in the Williams help to organise the first committed activist and Marxist. be one of the first narratives by Thomas was born the son of a Marcus Garvey is a hero to many George Padmore (pictured below) Eric Williams was the first prime Born in Grenada, Walter Rodney Anglican Church. Born in Barbados Pan African congress in London He worked alongside other giants African woman. Her work had free slave. Proficient in a number across the world. Born in Jamaica, helped form the International minister of newly independent (pictured below) was a political he went to West Africa as a in 1900.The Pan African movment like George Padmore and Eric an important influence on later of languages he later became a he spent most of his life in America African Service Bureau in 1937, Trinidad (see Trinidad timeline activist who died in Guyana. -

Legacies and Links

MAKINGMAKING emancipationFREEDOM1838 © emancipationFREEDOM1838 © WINDRUSH FOUNDATION EDUCATION PACK SESSION TITLE Legacies and Links: SESSION NUMBER: 5 Key Stage 2 MAKING emancipationFREEDOM1838 © WINDRUSH FOUNDATION EDUCATION PACK Key Stage 2 Session 5: Legacies and Links Henry Sylvester Williams (c.1869-1911) Henry Sylvester Williams was born in Trinidad After the conference Henry Sylvester Williams in the 1860s. Some historians say his birth year travelled to Jamaica, Trinidad and the USA was 1867, but other records say it was 1869. to set up branches of the international Pan Although his family were not very wealthy African Association. He also launched a he was able to have a good education and journal in 1901 called The Pan African. In qualified as a school teacher in 1886. He 1902 he qualified as a barrister and worked was also very interested in politics and the in Britain, South Africa and Trinidad. He died law and helped to set up the first Elementary in Trinidad in 1911. Teachers’ Union in Trinidad. During the 1890s he travelled to the USA, Canada and England to study law. In 1897 he set up an African Association in England and campaigned to improve the welfare of African and Caribbean people in colonies throughout the British Empire. He also started to plan an important international conference where famous political campaigners and writers could meet to discuss ways to improve African people’s lives around the world. In 1900 the first Pan-African Conference was held in London at Westminster Town Hall. 2 MAKING emancipationFREEDOM1838 © WINDRUSH FOUNDATION EDUCATION PACK Key Stage 2 Session 5: Legacies and Links THINGS TO DO: • Find out more information about Henry Sylvester Williams and create a storyboard about his life. -

HISU9S3: Reputations in History | University of Stirling

10/01/21 HISU9S3: Reputations in History | University of Stirling HISU9S3: Reputations in History View Online Alastair Mann 100 Great Black Britons - Mary Seacole (no date). Available at: http://www.100greatblackbritons.com/bios/mary_seacole.html. Adair, D. (no date) Fame and the founding fathers. Adams, R. G. (1922) Political ideas of the American Revolution: Britannic-American contributions to the problem of Imperial Organization 1765 to 1775. Durham, North Carolina: Trinity College Press. Adams, R. G. (1958) ‘John Adams as a Britannic statesman’, in Political ideas of the American Revolution: Britannic-American contributions to the problem of imperial organization, 1765 to 1775. 3rd edn. New York: Barnes & Noble, pp. 107–127. Available at: https://contentstore.cla.co.uk/secure/link?id=893e0606-7c55-e611-80c6-005056af4099. A. Lang (1905) John Knox and the reformation. London: Longmans, Green & Co. Available at: http://archive.org/details/johnknoxreformat00lang. Aldred, Guy Alfred (1940) John Maclean. Glasgow: Strickland Press; Bakunin Press. Available at: http://www.stir.ac.uk/is/staff/forms/request/. Alldridge, L. (1885) Florence Nightingale, Frances Ridley Havergal, Catherine Marsh, Mrs. Ranyard. Available at: https://archive.org/details/florencenighting00alld. Amy Robinson (1994) ‘Authority and the Public Display of Identity: “Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands”’, Feminist Studies, 20(3), pp. 537–557. Available at: http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.stir.ac.uk/stable/3178185. An Autobiographical Note by Nelson Mandela, 1964 | South African History Online (no date). Available at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/articles/autobiographical-note-nelson-mandela-1964. Anderson, D. (1998) ‘Extinguishing the lamp: the crisis in nursing, IN: Come back Miss Nightingale: trends in professions today’, in Come back Miss Nightingale: trends in professions today. -

BLACK HISTORY MONTH Beyond a Month

BLACK HISTORY MONTH Beyond a month PROGRAMME 2016 Welcome from Professor Anne-Marie Kilday Pro Vice-Chancellor (Staff Experience), Chair of Brookes Race Equality Action Group and Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences I am delighted that Oxford Brookes is taking an active part in marking Black History Month this year, and invite all members of Oxford Brookes and the wider local community to join us. We aim to raise awareness across the university and beyond of the past, present and future contribution of Black communities to our social, economic, political, cultural and intellectual life in the UK. Brookes’ first programme for Black History Month goes “Beyond a Month…..” to link with our wider race equality agenda, connect with the development of our Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Staff Network, and give increased positive profile and visibility to the experience of our BME staff and students. Black History Month especially promotes knowledge and awareness across all communities of the experience and contribution of Black people of African and African Caribbean heritage to British and global society. Join us as we look back at the history as well as looking forward to the future in creating a society that works for all. This guide lists events which will be happening here at Oxford Brookes University and across the city, and includes a range of information, profiles and links to other resources. We hope you find this useful and welcome future contributions and ideas for developing our work for Black History Month: Beyond -

Pioneers & Champions

WINDRUSH PIONEERS & CHAMPIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS WINDRUSH PIONEERS Windrush Foundation is very grateful for the contributions Preface 4 David Dabydeen, Professor 82 to this publication of the following individuals: Aldwyn Roberts (Lord Kitchener) 8 David Lammy MP 84 Alford Gardner 10 David Pitt, Lord 86 Dr Angelina Osborne Allan Charles Wilmot 12 Diana Abbott MP 88 Constance Winifred Mark 14 Doreen Lawrence OBE, Baroness 90 Angela Cobbinah Cecil Holness 16 Edna Chavannes 92 Cyril Ewart Lionel Grant 18 Floella Benjamin OBE, Baroness 94 Arthur Torrington Edwin Ho 20 Geoff Palmer OBE, Professor Sir 96 Mervyn Weir Emanuel Alexis Elden 22 Heidi Safia Mirza, Professor 98 Euton Christian 24 Herman Ouseley, Lord 100 Marge Lowhar Gladstone Gardner 26 James Berry OBE 102 Harold Phillips (Lord Woodbine) 28 Jessica Huntley & Eric Huntley 104 Roxanne Gleave Harold Sinson 30 Jocelyn Barrow DBE, Dame 106 David Gleave Harold Wilmot 32 John Agard 108 John Dinsdale Hazel 34 John LaRose 110 Michael Williams John Richards 36 Len Garrison 112 Laurent Lloyd Phillpotts 38 Lenny Henry CBE, Sir 114 Bill Hern Mona Baptiste 40 Linton Kwesi Johnson 116 42 Cindy Soso Nadia Evadne Cattouse Mike Phillips OBE 118 Norma Best 44 Neville Lawrence OBE 120 Dione McDonald Oswald Denniston 46 Patricia Scotland QC, Baroness 122 Rudolph Alphonso Collins 48 Paul Gilroy, Professor 124 Verona Feurtado Samuel Beaver King MBE 50 Ron Ramdin, Dr 126 Thomas Montique Douce 52 Rosalind Howells OBE, Baroness 128 Vincent Albert Reid 54 Rudolph Walker OBE 130 Wilmoth George Brown 56 -

September 2020 PRESS RELEASE

September 2020 PRESS RELEASE Racing Green Pictures announces sponsorship of 100 Great Black Britons Young People’s Competition as part of Black History Month and will invite winners to the film set to meet cast London, September 2020: Last week saw the release of the long-overdue book, 100 Great Black Britons written by Patrick Vernon OBE and Dr Angelina Osborne. The authors launched their ground-breaking 100 Great Black Britons campaign in 2003, which invited the public to vote for the Black Briton they most admired and the full list comes to fruition in the book. Voted No.1 Greatest Black Briton by public Internet vote was the little-known Jamaican nurse, Mary Seacole; a statue of Mary was then commissioned and erected in the St Thomas’ Hospital garden in Westminster in 2004. Racing Green Pictures is to sponsor the 100 Great Black Britons Young People 16-25-year-old category and donate the winning prizes of laptops, school vouchers and books to the winners and runners up. The top prize will be an experiential one, an exciting opportunity for the winners to visit the ‘Seacole’ film set, the edit suite and to meet members of the cast. Billy Peterson, CEO Racing Green Pictures says, “I am thrilled that the 100 Black Britons is finally released, and that Mary Seacole is No. 1.The story of her life, ‘Seacole’ is a true, socially impactful, humanitarian film about a strong woman of colour persevering against all odds is exactly what today’s audiences are thirsting for. Racing Green plans to invite the winners of the competition to the film set so they can learn through experience how her story will be told.