What Happened in Cyprus?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zimra Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for the Period 08 to 14 July

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 08 TO 14 JULY 2021 USD BASE CURRENCY - USD DOLLAR CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 650.4178 0.0015 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 4.1598 0.2404 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 95.9150 0.0104 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 42.8000 0.0234 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 1.3329 0.7503 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 8.9490 0.1117 AUSTRIA EUR 0.8454 1.1829 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 63.9250 0.0156 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.3760 2.6596 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 14.3346 0.0698 BELGIUM EUR 0.8454 1.1829 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.8454 1.1829 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 10.9709 0.0912 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 1.4232 0.7027 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 5.1970 0.1924 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 410.9200 0.0024 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.7241 1.3810 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 900.0228 0.0011 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 1983.5620 0.0005 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 8.7064 0.1149 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 1.2459 0.8026 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.3845 2.6008 CHINESE RENMINBI YUAN CNY 6.4690 0.1546 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 158.3558 0.0063 CUBAN PESO CUP 24.0957 0.0415 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 3.8154 0.2621 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 PORTUGAL EUR 0.8454 1.1829 CZECH KORUNA CZK 21.6920 0.0461 QATARI RIYAL QAR 3.6400 0.2747 DANISH KRONER DKK 6.2866 0.1591 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 74.2305 0.0135 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 15.6900 0.0637 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 1001.5019 0.0010 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 43.9164 0.0228 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 3.7500 0.2667 EURO EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 1.3478 0.7419 FINLAND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SPAIN EUR 0.8454 1.1829 FRANCE EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 14.3346 0.0698 GERMANY -

Currency Conversions” Also Apply

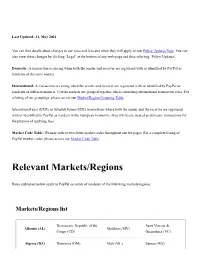

Last Updated: 31, May 2021 You can find details about changes to our rates and fees and when they will apply on our Policy Updates Page. You can also view these changes by clicking ‘Legal’ at the bottom of any web-page and then selecting ‘Policy Updates’. Domestic: A transaction occurring when both the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of the same market. International: A transaction occurring when the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of different markets. Certain markets are grouped together when calculating international transaction rates. For a listing of our groupings, please access our Market/Region Grouping Table. International euro (EUR) or Swedish krona (SEK) transactions where both the sender and the receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as resident in the European Economic Area (EEA) are treated as domestic transactions for the purpose of applying fees. Market Code Table: We may refer to two-letter market codes throughout our fee pages. For a complete listing of PayPal market codes, please access our Market Code Table. Relevant Markets/Regions Rates published below apply to PayPal accounts of residents of the following markets/regions: Markets/Regions list Democratic Republic of the Saint Vincent & Albania (AL) Maldives (MV) Congo (CD) Grenadines (VC) Algeria (DZ) Dominica (DM) Mali (ML) Samoa (WS) Marshall Islands Sao Tome & Principe Andorra (AD) Djibouti (DJ) (MH) (ST) Angola (AO) Dominican Republic (DO) Monaco (MC) Saudi Arabia -

Information Guide Economic and Monetary Union

Information Guide Economic and Monetary Union A guide to the European Union’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), with hyperlinks to sources of information within European Sources Online and on external websites Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................... 2 Background .......................................................................................................... 2 Legal basis ........................................................................................................... 2 Historical development of EMU ................................................................................ 4 EMU - Stage One ................................................................................................... 6 EMU - Stage Two ................................................................................................... 6 EMU - Stage Three: The euro .................................................................................. 6 Enlargement and future prospects ........................................................................... 9 Practical preparations ............................................................................................11 Global economic crisis ...........................................................................................12 Information sources in the ESO database ................................................................19 Further information sources on the internet .............................................................19 -

Accession to EMU - Lessons to Learn for Romania

Bulletin UASVM Horticulture, 69(2)/2012 Print ISSN 1843-5254; Electronic ISSN 1843-5394 Accession to EMU - Lessons to Learn for Romania Roxana BADIRCEA1) 1) Faculty of Economic and Business Administration, University of Craiova, A.I.Cuza, no.13; [email protected]. Abstract. Among the countries that became UE members in 2004, five of them, namely: Cyprus, Malta, Slovenia, Slovakia and Estonia also adopted Euro. The paper analyses the way these states accomplished the convergence criteria in order to emphasize the difficulties they encountered and how they solved all these problems, lessons to learn for Romania in the EMU integration process. Keywords: EMU, accession, convergence criteria, inflation, budget deficit, long-term interest rates, gross public debt INTRODUCTION After their accession to the EU in 2004, the new ten member states intensified their efforts to enter the Exchange Rate Mechanism II – regarded as a “waiting room” of the euro area that offers at best little value-added and may even entail certain risks (Backé, P. et all., 2004). During this time, the economic, financial and institutional differences between those countries and those belonging to the euro area were significant, and consequently, the efforts to achieve the convergence increased, but many times, implying high costs. The fundamental characteristic of the ten countries that joined the EU in 2004, compared to the twelve states, already part of the Economic and Monetary Union, was the high difference between the levels of development measured through the GDP/capita. In addition to the fact that certain sectors of the economy of these countries had not gotten completely past the transition process to the market economy, there was the danger that once the convergence process had accelerated, the level of volatility of the economic growth would increase. -

Understanding of the Financial Crisis in Cyprus, Its Effects and the Post Crisis Strategy

Understanding of the Financial Crisis in Cyprus, Its Effects and the Post Crisis Strategy Master Thesis For the Degree of Politics & Economics of Contemporary Eastern and South-eastern Europe By Eirini Kouloudi Under the Guidance of Professor Fwtios Siokis Department of Balkan, Slavic and Oriental Studies. Submitted to: University of Macedonia October, 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that this very thesis is a work of my own and all the references used while gathering of relevant data have been properly indicated. I am well aware that a false declaration may have serious consequences. Date: ---------------------------------------- (Signature) Cypriot Financial Crisis Page 1 Abstract This paper focuses on Cypriot economy with a special emphasis on the effects and aftermath of the financial crisis that it has gone through. An overview of the island’s economy and its key elements will help to get the thorough understanding of what had gone behind the screen. Cypriot banking system in general and the situation around the globe that helped shape the crisis will form part of the project. Situation around Europe, Admittance into EU and ultimately Euro played an equally important part in the financial crisis history of the country. Banking operations and especially the expansion program devised by the biggest banks will be criticised. Early symptoms and Cypriot entry into the financial difficulty will be highlighted along with all the other factors that contributed to the ultimate demise of the huge banking empire. The crisis period will form a part of the paper with all the relevant factors be considered. European Union’s part and other unfortunate events will be analysed throughout in the later area of this paper. -

The Effect of the Pricing Policy of the Cypriot Banks Upon Accession to the Euro Area As at 31/12/2007

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Middlesex University Research Repository The Effect of the Pricing Policy of the Cypriot Banks Upon Accession to the Euro Area as at 31/12/2007 Marios Soupashis DPROF 2010 The Effect of the Pricing Policy of the Cypriot Banks Upon Accession to the Euro Area as at 31/12/2007 A project submitted to Middlesex University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Professional Studies Marios Soupashis National Center for Work Based Learning Partnerships Middlesex University May 2010 MAY 2010 2 Declaration I hereby declare that this research project has been conducted by myself. Except where reference is made in the text of the research project, this research project contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a research project by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the research project. This work is a record written by myself. This research project has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in the any other tertiary institution. Some of the results obtained in this research project have been presented as follows: meeting, report content and newspaper article publication. Marios Soupashis MAY 2010 3 Acknowledgement I would like to express my gratitude to all those who gave me the possibility to complete this thesis. I want to thank the Bank of Cyprus Group and especially Mr. -

Emu and the Introduction of the Euro: Macroeconomic Implications for the Cypriot Economy

EMU AND THE INTRODUCTION OF THE EURO: MACROECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS FOR THE CYPRIOT ECONOMY by George Kyriacou and George Syrichas* 1. INTRODUCTION The third and final stage of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was successfully launched on January 1, 1999. This monumental development, which has no parallel in history, builds upon the already achieved progress in strengthening political, economic, and monetary ties within the European Union and provides, among other things, for unified monetary and exchange rate policies and for the replacement of national currencies with a single common currency, the euro. Certainly, the impact of this momentous change is not confined within the Union. The consequences for the international monetary system as a whole as well as for individual countries or regions inside and outside the European Union are expected to be significant. In particular, potential EU members like Cyprus, are affected by EMU not only in terms of experiencing a direct economic impact through economic linkages, but also in terms of having to reform and adjust their structural and macroeconomic policies, with the ultimate goal of meeting the Maastricht criteria. This paper aims at examining the historic developments taking place in Europe and assess their macroeconomic impact on the economy of Cyprus. The structure of the paper is as follows: In section 2, the impact of EMU and the introduction of the euro on the EMU participants, that is the countries of the so called euro area or euro zone, is examined. In section 3, the global impact of EMU is described, while in section 4 an analysis of the macroeconomic effects of EMU on the economy of Cyprus is undertaken. -

The Palestine Currency Board Its History and Currency

SAE./No.184/June 2021 Studies in Applied Economics THE PALESTINE CURRENCY BOARD ITS HISTORY AND CURRENCY Howard M. Berlin Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise The Palestine Currency Board: Its History and Currency By Howard M. Berlin About the Series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the direction of Prof. Steve H. Hanke, Founder and Co-Director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise ([email protected]). This working paper is one in a series on currency boards. The currency board working papers fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of the subject. About the Author Dr. Howard M. Berlin ([email protected]) received BEE and BA degrees from the University of Delaware, an MS degree in electrical engineering from Washington University, and an MEd degree in computer science education as well as a doctorate in educational statistics from Widener University. He had been elected as a Senior Member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), and elected to RESA, Sigma Xi, and Phi Theta Kappa honor societies. Dr. Berlin had been an electrical engineer with the U.S. Department of Defense for 13 years, during which time he was awarded three U.S. patents. He then retired after 22 years from the Electronic/Electrical Engineering Technology faculty at the Stanton Campus of Delaware Technical Community College. Dr. Berlin has also taught undergraduate and graduate courses at several universities as well as short courses at conferences. He is the author of many magazine articles, journal articles, and editorials, in addition to over 30 books, that cover diverse areas of electronic circuit design, financial markets, numismatics, and the cinema. -

Currencies of the World

The World Trade Press Guide to Currencies of the World Currency, Sub-Currency & Symbol Tables by Country, Currency, ISO Alpha Code, and ISO Numeric Code € € € € ¥ ¥ ¥ ¥ $ $ $ $ £ £ £ £ Professional Industry Report 2 World Trade Press Currencies and Sub-Currencies Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies of the World of the World World Trade Press Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s 800 Lindberg Lane, Suite 190 Petaluma, California 94952 USA Tel: +1 (707) 778-1124 x 3 Introduction . 3 Fax: +1 (707) 778-1329 Currencies of the World www.WorldTradePress.com BY COUNTRY . 4 [email protected] Currencies of the World Copyright Notice BY CURRENCY . 12 World Trade Press Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies Currencies of the World of the World © Copyright 2000-2008 by World Trade Press. BY ISO ALPHA CODE . 20 All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the express written permission of the Currencies of the World copyright holder is unlawful. Requests for permissions and/or BY ISO NUMERIC CODE . 28 translation or electronic rights should be addressed to “Pub- lisher” at the above address. Additional Copyright Notice(s) All illustrations in this guide were custom developed by, and are proprietary to, World Trade Press. World Trade Press Web URLs www.WorldTradePress.com (main Website: world-class books, maps, reports, and e-con- tent for international trade and logistics) www.BestCountryReports.com (world’s most comprehensive downloadable reports on cul- ture, communications, travel, business, trade, marketing, -

Euro Ordinance 2007.Indd

Ordinance 18 of 2007 Published in Gazette No. 1470 of 14th August 2007 EURO ORDINANCE 2007 An Ordinance to provide for the adoption of the euro as legal tender in the Sovereign Base Areas and for related matters R. H. LACEY 7th August 2007. ADMINISTRATOR BE it enacted by the Administrator of the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia as follows:— Part 1 PRELIMINARY PROVISIONS 1. Short title This Ordinance may be cited as the Euro Ordinance 2007. 2. Interpretation. In this Ordinance - “adoption date” means 1st January 2008 which is the date on which the euro becomes legal tender in the Republic; “bank” has the meaning assigned to this term under the Banking Activities Law 1997 of the Republic (Law No. 66(I)1997) as such Law may be amended from time to time; “Central Bank” means the Central Bank of Cyprus; “Code of Fair Pricing” means a code issued by the Chief Officer in accordance with section 25(3); “Companies Law” means the Companies Law of the Republic, as given effect to in the Areas in accordance with the Companies Ordinance 2007(a); “conversion rate” means the irrevocable conversion rate adopted for the pound by the Council of the European Union on 10th July 2007, namely €1 = £0.585274, and as referred to in the corresponding Law; “cooperative credit institution” means a cooperative society as defined under the Cooperative Societies Ordinance(b); 157 “corresponding law” means the Euro Law 2007 of the Republic (Law 33(I)/2007) as such law may be amended from time to time; “dual display of prices” means the dual display of -

Exchange Form

EXCHANGE FORM BANKNOTES (A) To exchange your foreign currency and coins, fill out this exchange form and send it, along with your banknotes and coins to our address: Currency Name amount L.O.C. - 3rd Floor - 207 Regent Street - London W1B 3HH - United Kingdom American Dollar USD Fill in part A to exchange banknotes and part C for coins. Write down the amount per currency Australian Dollar AUD submitted for exchange. Fill in your personal details, and preferred payment currency and method Austrian Schilling ATS in part B and sign and date the declaration in part D. When the exchange form is filled out completely and signed, send it along with your banknotes and coins to our address. Upon receipt Belgian Franc BFR of your consignment, we will send you a confirmation email and a link to our feedback form. A few Brunei Dollar BND working days later you will receive the exchange value for your submitted notes and coins. Canadian Dollar CAD Croatian Kuna HRK Cypriot Pound CYP PAYMENT DETAILS AND PREFERENCES (B) Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK first name + name Deutsche Mark DEM house number + street Dutch Guilder NLG postcode + city Egyptian Pound EGP Estonian Kroon EEK county/state/province Euro EUR country Finnish Markkaa FIM e-mail address * French Franc FRF ( ) Greek Drachma GRD IBAN code (**) Hong Kong Dollar HKD (or sort code Hungarian Forint HUF Indian Rupee INR + account number) Irish Pound IEP account holder (**) Israeli Shekel ILS preferred payment method Paypal Cheque Italian Lira ITL Japanese Yen JPY Bank Transfer Charity (***) Luxembourgish Franc LUF preferred payout currency Pounds Euros Maltese Lira MTL US Dollars Moroccan Dirham MAD New Zealand Dollar NZD (*) e-mail address to which we will send the confirmation email. -

Pound”? Find 29 Synonyms and 30 Related Words for “Pound” in This Overview

Need another word that means the same as “pound”? Find 29 synonyms and 30 related words for “pound” in this overview. Table Of Contents: Pound as a Noun Definitions of "Pound" as a noun Synonyms of "Pound" as a noun (20 Words) Usage Examples of "Pound" as a noun Pound as a Verb Definitions of "Pound" as a verb Synonyms of "Pound" as a verb (9 Words) Usage Examples of "Pound" as a verb Associations of "Pound" (30 Words) The synonyms of “Pound” are: cypriot pound, pound sign, hammer, hammering, pounding, dog pound, syrian pound, lbf., british pound, british pound sterling, pound sterling, quid, irish pound, irish punt, punt, lb, sudanese pound, egyptian pound, ezra loomis pound, ezra pound, lumber, pound off, poke, thump, beat, pound up, impound, ram, ram down Pound as a Noun Definitions of "Pound" as a noun According to the Oxford Dictionary of English, “pound” as a noun can have the following definitions: United States writer who lived in Europe; strongly influenced the development of modern literature (1885-1972. A public enclosure for stray or unlicensed dogs. The basic unit of money in Syria; equal to 100 piasters. The basic unit of money in Lebanon; equal to 100 piasters. 16 ounces avoirdupois. GrammarTOP.com The basic unit of money in Great Britain and Northern Ireland; equal to 100 pence. Formerly the basic unit of money in Ireland; equal to 100 pence. The basic monetary unit of the UK, equal to 100 pence. The basic unit of money in the Sudan; equal to 100 piasters. A unit of weight equal to 16 oz.