Are the New Member States on the Fast Track to the EMU?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scandinavian Argument for Multi-Level Economic and Monetary Union (EMU)

Running head: THE SCANDINAVIAN ARGUMENT FOR MULTI-LEVEL EMU Looking North: The Scandinavian Argument for Multi-Level Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) Malcolm Thomson University of Victoria Paper Submitted for the “Claremont-UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union” Scripps College, Claremont, California April 5-6, 2018 THE SCANDINAVIAN ARGUMENT FOR MULTI-LEVEL EMU 1 The European Union (EU) is undergoing a significant period in its existence marked by various crises at both member state and supranational levels. While previous literature has stated, “it is difficult to remember a time when the EU or its predecessors were not facing a crisis of one sort or another” (Hodson & Puetter, 2016, p. 365), it can be argued that the various crises that the European Union has faced over the past fifteen years have shifted the collectively-held conception of an integrated and cooperative European Union into a splintered and divided institution. The global financial crisis, the subsequent sovereign debt crisis, and the migrant crisis are causing member states to re-evaluate their position within the EU (Verdun, 2016). This re- evaluation is taking form in multiple iterations and at various levels of intensities, and is forcing the EU to look at ways in which it can adapt and evolve in order better accommodate the quickly changing needs of the elements that compose it. One of the most visible occurrences of this evolution in European integration is seen within the EU’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). EMU played a large role in the sovereign debt crisis, as its “incomplete” structure not only helped to create the crisis, but also prevented quicker action from being taken in order to help those most affected (Verdun, 2016, p. -

Introduction of the Euro at the Bratislava Stock Exchange: the Most Frequently Asked Questions

Introduction of the Euro at the Bratislava Stock Exchange: The Most Frequently Asked Questions Starting from the day of the euro introduction, asset values denominated in the Slovak currency are regarded as asset values denominated in the euro currency. How is this stipulation reflected in the conversion of nominal value of shares that form registered capital as well as other securities? Similar to asset values in general, the nominal values of shares that form registered capital and other securities denominated in the Slovak currency are, starting from 1 January 2009, regarded as the nominal values and securities denominated in the euro, based on a conversion and rounding of their nominal values according to a conversion rate and other rules applying to the euro changeover. This condition, however, does not affect the obligation of legal entities to ensure and perform a change, conversion and rounding of the nominal value of shares that form registered capital as well as other securities from the Slovak currency to the euro, in a manner according to the Act on the Euro Currency Introduction in the Slovak Republic and separate legislation. What method is used to convert the nominal value of securities from the Slovak currency to the euro currency? Every issuer of securities denominated in the Slovak currency is obligated to perform the change, conversion and rounding of the nominal value of securities from the Slovak koruna to the euro currency. In the case of equity securities, the conversion of their asset value must be performed simultaneously with the conversion of registered capital. The statutory body of a relevant legal entity is entitled to adopt and carry out the decision on such conversion. -

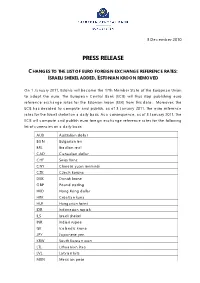

Press Release Changes to the List of Euro Foreign Exchange Reference

3 December 2010 PRESS RELEASE CHANGES TO THE LIST OF EURO FOREIGN EXCHANGE REFERENCE RATES: ISRAELI SHEKEL ADDED, ESTONIAN KROON REMOVED On 1 January 2011, Estonia will become the 17th Member State of the European Union to adopt the euro. The European Central Bank (ECB) will thus stop publishing euro reference exchange rates for the Estonian kroon (EEK) from this date. Moreover, the ECB has decided to compute and publish, as of 3 January 2011, the euro reference rates for the Israeli shekel on a daily basis. As a consequence, as of 3 January 2011, the ECB will compute and publish euro foreign exchange reference rates for the following list of currencies on a daily basis: AUD Australian dollar BGN Bulgarian lev BRL Brazilian real CAD Canadian dollar CHF Swiss franc CNY Chinese yuan renminbi CZK Czech koruna DKK Danish krone GBP Pound sterling HKD Hong Kong dollar HRK Croatian kuna HUF Hungarian forint IDR Indonesian rupiah ILS Israeli shekel INR Indian rupee ISK Icelandic krona JPY Japanese yen KRW South Korean won LTL Lithuanian litas LVL Latvian lats MXN Mexican peso 2 MYR Malaysian ringgit NOK Norwegian krone NZD New Zealand dollar PHP Philippine peso PLN Polish zloty RON New Romanian leu RUB Russian rouble SEK Swedish krona SGD Singapore dollar THB Thai baht TRY New Turkish lira USD US dollar ZAR South African rand The current procedure for the computation and publication of the foreign exchange reference rates will also apply to the currency that is to be added to the list: The reference rates are based on the daily concertation procedure between central banks within and outside the European System of Central Banks, which normally takes place at 2.15 p.m. -

THE IMPACT of the EURO ADOPTION on SLOVAKIA Thesis

THE IMPACT OF THE EURO ADOPTION ON SLOVAKIA Thesis by Anna Gajdošová Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Business Administration State University of New York Empire State College 2019 Reader: Tanweer Ali Statutory Declaration / Čestné prohlášení I, Anna Gajdošová, declare that the paper entitled: The Impact of the Euro Adoption on Slovakia was written by myself independently, using the sources and information listed in the list of references. I am aware that my work will be published in accordance with § 47b of Act No. 111/1998 Coll., On Higher Education Institutions, as amended, and in accordance with the valid publication guidelines for university graduate theses. Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. Jsem vědoma, že moje práce bude zveřejněna v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb., o vysokých školách ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a v souladu s platnou Směrnicí o zveřejňování vysokoškolských závěrečných prací. In Prague, 06.08.2019 Anna Gajdošová Acknowledgement I would like to express my special thanks to my mentor, Prof. Tanweer Ali, for his useful advice, constructive feedback, and patience through the whole process of writing my senior project. I would also like to thank my family for supporting me during this whole journey of my studies. Table of Contents Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 8 1. Historical Overview -

Introduction of the Euro in Slovakia Summary

The Gallup Organization Flash EB No 187 – 2006 Innobarometer on Clusters Flash Eurobarometer European Commission Introduction of the euro in Slovakia Summary Fieldwork: September 2008 Report: November 2008 The Gallup The Organization This survey was requested by Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs and coordinated by Directorate General Communication This document does not represent the point of view of the European Commission.Analytical Report, page 1 Flash Eurobarometer 249 – 249 Eurobarometer Flash The interpretations and opinions contained in it are solely those of the authors. Flash EB Series #249 Introduction of the euro in Slovakia Survey conducted by The Gallup Organization, Hungary upon the request of the European Commission, Directorate-General “Economic and Financial Affairs” Coordinated by Directorate-General Communication This document does not represent the point of view of the European Commission. The interpretations and opinions contained in it are solely those of the authors. THE GALLUP ORGANIZATION Summary Flash EB No 249 – Introduction of the euro in Slovakia Introduction The EU’s new Member States1 can adopt the common currency, the euro, once they have fulfilled the criteria defined in the Maastricht Treaty. All of those Member States are expected to join the euro area in the coming years. Slovenia, Cyprus and Malta have already joined the euro area in 2007 and 2008 respectively, while Slovakia is currently preparing to changeover from the Slovak koruna, its national currency, to the euro in January 2009. Concerning the introduction of the euro in the new EU Member States, the European Commission is keeping track of general opinions, the levels of knowledge and information and the familiarity with the single currency among citizens of the respective countries. -

Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: the Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia

ADBI Working Paper Series REGIONAL AND GLOBAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: THE RECENT EUROPEAN EXPERIENCE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL COOPERATION IN ASIA Zsolt Darvas No. 712 April 2017 Asian Development Bank Institute Zsolt Darvas is senior fellow at Bruegel and senior research Fellow at the Corvinus University of Budapest. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Darvas, Z. 2017. Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: The Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia. ADBI Working Paper 712. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/regional-and-global-financial-safety-nets Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected] Paper prepared for the Conference on Global Shocks and the New Global/Regional Financial Architecture, organized by the Asian Development Bank Institute and S. -

Baltic Monetary Regimes in the Xxist Century

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Viksnins, George J. Article — Digitized Version Baltic monetary regimes in the XXIst century Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Viksnins, George J. (2000) : Baltic monetary regimes in the XXIst century, Intereconomics, ISSN 0020-5346, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 35, Iss. 5, pp. 213-218 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/40777 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu EU ENLARGEMENT member states, the candidates should expect the dangers of inaction are even greater because the enlargement to be in a state of fluidity. existing member states may use their veto on • Second, the fact that uncertainty cannot be accession of new members to protect their broader interests. -

The Quest for Monetary Integration – the Hungarian Experience

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The quest for monetary integration – the Hungarian experience Zoican, Marius Andrei University of Reading, Henley Business School 5 April 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/17286/ MPRA Paper No. 17286, posted 14 Sep 2009 23:56 UTC The Quest for Monetary Integration – the Hungarian Experience Working paper Marius Andrei Zoican visiting student, University of Reading Abstract From 1990 onwards, Eastern European countries have had as a primary economic goal the convergence with the traditionally capitalist states in Western Europe. The usage of various exchange rate regimes to accomplish the convergence of inflation and interest rates, in order to create a fully functional macroeconomic environment has been one of the fundamental characteristics of states in Eastern Europe for the past 20 years. Among these countries, Hungary stands out as having tried a number of exchange rate regimes – from the adjustable peg in 1994‐1995 to free float since 2008. In the first part, this paper analyses the macroeconomic performance of Hungary during the past 15 years as a function of the exchange rate regime used. I also compare this performance, where applicable, with two similar countries which have used the most extreme form of exchange rate regime: Estonia (with a currency board) and Romania, who never officialy pegged its currency and used a managed float even since 1992. The second part of this paper analyzes the overall Hungarian performance from the perspective of the Optimal Currency Area theory, therefore trying to establish if, after 20 years of capitalism, and a large variety of monetary policies, Hungary is indeed prepared to join the European Monetary Union. -

What Happened in Cyprus?

What Happened in Cyprus? Alexander Michaelides1 Imperial College Business School, University of Cyprus, CEPR, CFS and NETSPAR 15 March 2014 Abstract This is a case study of how a country nearly reached bankruptcy in March 2013, within five years from entering the Eurozone. The magnitude of the requested assistance is extremely large relative to GDP (100%) and studying this event provides useful lessons for avoiding such crises in the future. The crisis resulted from a worsening European economic environment (especially in Greece), bad choices with regards to public finances, weak corporate governance within the local banking sector, inadequate and/or difficult regulation of cross-border banking, worsening competitiveness, and bad political decisions at the European and, especially, the local (Cypriot) level. Local politics, reflected in short term political calculations and/or inadequate understanding of the magnitude of the crisis, delayed corrective action for 18 months until election time, making a bad situation almost impossible to deal with. Overconfidence can be one behavioural explanation for why local politicians ignored the dramatic costs of inaction. 1 Imperial College London Business School, South Kensington Campus, London, SW7 2AZ: [email protected]. I would like to thank Dimitris Georgiou for excellent research assistance, three anonymous referees and the editor (Nicola Fuchs-Schundeln) for very useful comments. I served as a non- executive member of the Board of Directors of the Central Bank of Cyprus between May 28th 2013 and November 28th 2013. The analysis and opinions herein are not necessarily shared by the Central Bank of Cyprus or the Eurosystem more broadly. -

3 Issuing Activity and Currency Circulation

CHAPTER 3 3 ISSUING ACTIVITY AND CURRENCY CIRCULATION 3.1 CUMULATIVE NET ISSUANCE Euro banknotes accounted for almost the en- tire value of the CNI (98.5%), but only for 19% of The cumulative net issuance (CNI)10 of euro the CNI in terms of volume. Euro coins (includ- banknotes and coins in Slovakia had a total ing euro collector coins) made up the remaining value of €11.02 billion as at 31 December 2016, 81%. with euro banknotes accounting for €10.9 billion of that amount. The CNI increased in The cumulative net issuance as at 31 Decem- 2016 by 7.9% year on year (by €807.2 million), ber 2016 comprised almost 157.2 million euro which represented a slight acceleration com- banknotes and approximately 654 million euro pared with the previous year. The value of the coins, including collector coins. For the first item currency in circulation, corresponding to time, the €100 denomination had the largest Národná banka Slovenska’s allocated share in share of the total number of banknotes includ- the Eurosystem’s production of euro banknotes ed in the CNI, at 24%. The €50 denomination, (Banknote Allocation Key), amounted to around which had held that position in all the previ- €11.4 billion as at 31 December 2016.11 The dif- ous years following Slovakia’s adoption of the ference in value between the euro banknotes euro, saw its share drop to 23%. The coins is- issued in Slovakia and the currency in circulation sued in the highest volumes are the two low- item was €515 million. -

The History of the Romanian Monetary System in a European Context

Mugur Isărescu: The history of the Romanian monetary system in a European context Opening speech by Mr Mugur Isărescu, Governor of the National Bank of Romania, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Euro Exhibition at Banca Naţională a României, Bucharest, 10 March 2011. * * * Dear Mr González-Páramo, Your Excellencies, Distinguished guests, It is an honour for us and we are glad to welcome you today, at the opening of an exhibition not only educational and attractive, but also relevant considering Romania’s euro adoption. We do hope the Euro Exhibition that the National Bank of Romania is hosting, on behalf of Romania, will prove successful all the more so as our country is destination No. 10 of the European Central Bank’s travelling exhibition. Let me thank Mr. José Manuel González-Páramo for accepting to jointly launch the Euro Exhibition today in Bucharest where it will be open for about three months, here, in the old financial centre of Bucharest where the Romanian leu was born. The leu-euro relation is thus acquiring a symbolical dimension with a certain meaning in the current European context. The reference to the European context is neither conventional nor formal. It reveals that the Romanian leu is one of the strong historical bonds that put our country on the European map. Its roots in the olden leeuwendaalder or the Dutch lion-thaler show not only its descent from the former Dutch coin (and therefore its being related to the US dollar), but also its European dimension as ever since its birth, shortly after the creation of the modern Romanian state, our leu currency was French. -

Zimra Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for the Period 08 to 14 July

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 08 TO 14 JULY 2021 USD BASE CURRENCY - USD DOLLAR CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 650.4178 0.0015 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 4.1598 0.2404 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 95.9150 0.0104 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 42.8000 0.0234 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 1.3329 0.7503 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 8.9490 0.1117 AUSTRIA EUR 0.8454 1.1829 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 63.9250 0.0156 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.3760 2.6596 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 14.3346 0.0698 BELGIUM EUR 0.8454 1.1829 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.8454 1.1829 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 10.9709 0.0912 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 1.4232 0.7027 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 5.1970 0.1924 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 410.9200 0.0024 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.7241 1.3810 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 900.0228 0.0011 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 1983.5620 0.0005 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 8.7064 0.1149 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 1.2459 0.8026 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.3845 2.6008 CHINESE RENMINBI YUAN CNY 6.4690 0.1546 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 158.3558 0.0063 CUBAN PESO CUP 24.0957 0.0415 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 3.8154 0.2621 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 PORTUGAL EUR 0.8454 1.1829 CZECH KORUNA CZK 21.6920 0.0461 QATARI RIYAL QAR 3.6400 0.2747 DANISH KRONER DKK 6.2866 0.1591 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 74.2305 0.0135 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 15.6900 0.0637 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 1001.5019 0.0010 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 43.9164 0.0228 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 3.7500 0.2667 EURO EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 1.3478 0.7419 FINLAND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SPAIN EUR 0.8454 1.1829 FRANCE EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 14.3346 0.0698 GERMANY