Baltic Monetary Regimes in the Xxist Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

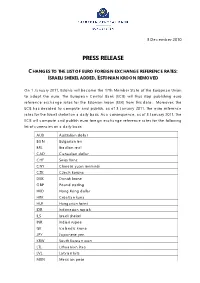

Press Release Changes to the List of Euro Foreign Exchange Reference

3 December 2010 PRESS RELEASE CHANGES TO THE LIST OF EURO FOREIGN EXCHANGE REFERENCE RATES: ISRAELI SHEKEL ADDED, ESTONIAN KROON REMOVED On 1 January 2011, Estonia will become the 17th Member State of the European Union to adopt the euro. The European Central Bank (ECB) will thus stop publishing euro reference exchange rates for the Estonian kroon (EEK) from this date. Moreover, the ECB has decided to compute and publish, as of 3 January 2011, the euro reference rates for the Israeli shekel on a daily basis. As a consequence, as of 3 January 2011, the ECB will compute and publish euro foreign exchange reference rates for the following list of currencies on a daily basis: AUD Australian dollar BGN Bulgarian lev BRL Brazilian real CAD Canadian dollar CHF Swiss franc CNY Chinese yuan renminbi CZK Czech koruna DKK Danish krone GBP Pound sterling HKD Hong Kong dollar HRK Croatian kuna HUF Hungarian forint IDR Indonesian rupiah ILS Israeli shekel INR Indian rupee ISK Icelandic krona JPY Japanese yen KRW South Korean won LTL Lithuanian litas LVL Latvian lats MXN Mexican peso 2 MYR Malaysian ringgit NOK Norwegian krone NZD New Zealand dollar PHP Philippine peso PLN Polish zloty RON New Romanian leu RUB Russian rouble SEK Swedish krona SGD Singapore dollar THB Thai baht TRY New Turkish lira USD US dollar ZAR South African rand The current procedure for the computation and publication of the foreign exchange reference rates will also apply to the currency that is to be added to the list: The reference rates are based on the daily concertation procedure between central banks within and outside the European System of Central Banks, which normally takes place at 2.15 p.m. -

Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: the Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia

ADBI Working Paper Series REGIONAL AND GLOBAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: THE RECENT EUROPEAN EXPERIENCE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL COOPERATION IN ASIA Zsolt Darvas No. 712 April 2017 Asian Development Bank Institute Zsolt Darvas is senior fellow at Bruegel and senior research Fellow at the Corvinus University of Budapest. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Darvas, Z. 2017. Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: The Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia. ADBI Working Paper 712. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/regional-and-global-financial-safety-nets Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected] Paper prepared for the Conference on Global Shocks and the New Global/Regional Financial Architecture, organized by the Asian Development Bank Institute and S. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 23.7.2013 COM(2013)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 23.7.2013 COM(2013) 540 final REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION Twelfth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area EN EN REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS Twelfth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area 1. INTRODUCTION Since the adoption of the euro by Estonia on 1 January 2011, the euro area consists of seventeen EU Member States. Among the remaining eleven Member States, nine Member States are expected to adopt the euro once the necessary conditions are fulfilled. Denmark and the United Kingdom have a special "opt-out"-status and are not committed to adopt the euro. This report assesses the state of play of the practical preparations for introducing the euro in Latvia and evaluates the progress made in preparing the changeover related communication campaign. Following the Council decision from 9 July 2013 concluding that the necessary conditions for euro adoption are fulfilled, Latvia will adopt the euro on 1 January 2014 ("€- day"). The conversion rate between the Latvian lats and the euro has been irrevocably fixed at 0.702804 Latvian lats to one euro. 2. STATE OF PLAY OF THE PREPARATIONS FOR THE CHANGEOVER IN LATVIA Latvia will be the sixth of the group of Member States which joined the EU in 2004 to adopt the euro. Latvia's original target date of 1 January 2008 foreseen in the Action Plan for Implementation of the Single European Currency of 1 November 2005 was subsequently reconsidered. -

Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia

ISSN 1725-3217 Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia EUROPEAN ECONOMY 3|2013 Economic and Financial Affairs The European Economy series contains important reports and communications from the Commission to the Council and the Parliament on the economic situation and developments, such as the European economic forecasts and the Public finances in EMU report. Unless otherwise indicated the texts are published under the responsibility of the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission to which enquiries should be addressed. Legal notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained in this publication, or for any errors which, despite careful preparation and checking, may appear. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN 978-92-79-28535-6 doi: 10.2765/40058 © European Union, 2013 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia EUROPEAN ECONOMY European Economy N° 3/2013 ABBREVIATIONS LV Latvia EA Euro area EU-27 European Union, 27 Member States EU-25 European Union, 25 Member States before 2007 (i.e. EU-27 excl. BG and RO) EU-15 European Union, 15 Member States before 2004 EUR Euro ECU European currency unit LVL Latvian lats USD US dollar SDR Special Drawing Rights AMR Alert Mechanism Report BoL Bank of Latvia BoP Balance of Payments -

Exchange Rate Statistics January 2013

Exchange rate statistics January 2013 Statistical Supplement 5 to the Monthly Report Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics January 2013 2 Deutsche Bundesbank Wilhelm-Epstein-Strasse 14 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 10 06 02 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany The Statistical Supplement Exchange rate statistics is published by the Deutsche Bundes bank, Frankfurt am Tel +49 69 9566-0 Main, by virtue of section 18 of the Bundesbank Act. or +49 69 9566 8604 It is available to interested parties free of charge. Fax +49 69 9566 8606 or 3077 Further statistical data, supplementing the Monthly Report, http://www.bundesbank.de can be found in the follow ing supplements. Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Banking statistics monthly Capital market statistics monthly The German-language version of the Statis tical Supple- Balance of payments statistics monthly ment Exchange rate statistics is published quarterly in Seasonally adjusted printed form. The Deutsche Bundesbank also publishes an business statistics monthly updated monthly edition in German and in English on its website. In cases of doubt, the original German-language Selected updated statistics are also available on the website. version is the sole authoritative text. Additionally, a CD-ROM containing roughly 40,000 pub- lished Bundesbank time series, which is updated monthly, ISSN 2190–8990 (online edition) may be obtained for a fee from the Bundesbank‘s Statistical Information Systems and Mathematical Methods Division Cut-off date: 14 January 2013. or downloaded from the Bundesbank‘s ExtraNet platform. Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics January 2013 3 Contents I Euro-area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1 Euro-area member states and irrevocable euro conversion rates in the third stage of European Economic and Monetary Union ................................................................. -

Revised Dates to Support the Adoption of the Euro in Latvia Suggested Routing: Authorization Contact, Clearing Contact, Principal Contact, Settlement Contact

Revised Dates to Support the Adoption of the Euro in Latvia Suggested routing: Authorization Contact, Clearing Contact, Principal Contact, Settlement contact Topic(s): Currency, Settlement Applies to: P Acquirers P Issuers P Processors Summary: On 9 July 2013, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Latvia announced that the country of Latvia will adopt the euro as its official currency effective 1 January 2014. The Bank of Latvia also announced that all payments and transactions made by financial institutions in Latvia should be conducted in euros beginning at 00:00 local time on 1 January 2014. Action Indicator: M Mandate Effective Date: 1 January 2014 Overview As published in Global Operations Bulletin No. 8, 1 August 2013 and announced by the European Central Bank and the Bank of Latvia on 9 July 2013, the country of Latvia will adopt the euro as its official currency effective 00:00 local Latvian time on 1 January 2014. The European Central Bank announced that the irrevocable fixed exchange rate is set at 0.702804 Latvian lats to the euro. The Bank of Latvia has also announced that upon adoption of the euro, all payments and transactions made by financial institutions in Latvia should be conducted in euros. This article clarifies certain dates regarding support of the euro in Latvia. Customer Impact MasterCard currently supports the euro currency alphanumeric currency code EUR/978. MasterCard will continue to support the Latvian lats—alphanumeric currency code LVL/428—after Latvia adopts the euro for certain financial transactions as noted in the following paragraphs. Revised Dates to Support the Adoption of the Euro in Latvia Global Operations Bulletin No. -

Wiiw Research Report 314: Latvia: Economic Dynamism with Signs Of

Research Reports, No. 314, March 2005 Jari Jumpponen* Latvia: economic dynamism with signs of overheating** In 2004 Latvia joined the EU as well as NATO. The decision to phase out Russian- language high schools in September 2004 resulted in strong protests by Russian speakers. Relations with Russia are not quite relaxed, also on the score of the still unsigned border agreement. Latvia’s GDP grew by 7.8% in real terms in 2004, after 7.5% in 2003. The sectors recording the fastest growth were construction (12% output growth), manufacturing and transport and communications. Growth in gross fixed capital formation accelerated to 15% in 2004, after average annual growth rates of about 10% during the preceding five years. Private consumption has developed dynamically as well. Both investment and consumption have benefited from very low interest rates, which lately have even been slightly negative in real terms: borrowing has been expanding very rapidly. At the turn of the century, Russia started to construct new harbour capacities on the shores of the Baltic Sea (in the Gulf of Finland, close to St. Petersburg). The declared aim of that project was to bypass Latvian territory, with its Soviet-era transit routes for oil and other exports. Recently however some transit traffic business via Latvia has been resuming. Russian oil products transport via the transit pipeline increased by 22% in 2004 and cargo transport by rail rose as well. Cargo routes via Latvia offer a rational alternative, as ports in Latvia are ice-free in winter, unlike in the Gulf of Finland. In the early 2000s inflation had been under control. -

Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: the Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Darvas, Zsolt M. Working Paper Regional and global financial safety nets: The recent European experience and its implications for regional cooperation in Asia ADBI Working Paper, No. 712 Provided in Cooperation with: Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo Suggested Citation: Darvas, Zsolt M. (2017) : Regional and global financial safety nets: The recent European experience and its implications for regional cooperation in Asia, ADBI Working Paper, No. 712, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/163210 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/igo/ www.econstor.eu ADBI Working Paper Series REGIONAL AND GLOBAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: THE RECENT EUROPEAN EXPERIENCE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL COOPERATION IN ASIA Zsolt Darvas No. -

CENTRAL BANK CURRENCY EXCHANGE SWAP TRANSACTIONS in the FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET of LATVIA Gunita Mazure 1, Dr.Oec., Assoc

Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference “ECONOMIC SCIENCE FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT” No 46 Jelgava, LLU ESAF, 27-28 April 2017, pp. 287-294 CENTRAL BANK CURRENCY EXCHANGE SWAP TRANSACTIONS IN THE FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET OF LATVIA Gunita Mazure 1, Dr.oec., assoc. professor, Laura Vebere 2, Bc.oec. 1,2 Faculty of Economics and Social Development, Latvia University of Agriculture Abstract. Intervention by central banks, in terms of buying and selling foreign currency, has been a major activity in recent years. The intervention operations provide an opportunity for the commercial banks of Latvia to use foreign exchange reserves for the internal exchange market regulation, to reduce speculative interests and create confidence on the euro exchange rate stability in the future. In addition, which is very important in the research authors’ opinion, these operations contribute to the further development of interbank market. The present research is aimed to explore the Bank of Latvia currency intervention transactions during the period from 2008 to September 2016, using data research and data processing methods. The results of the study reveal that the political situation in Latvia and throughout the world significantly impacts the intervention transactions implemented by the Bank of Latvia. Any currency intervention, which is related to another EU currency, shall be performed with the main objective – to maintain the price stability. The Eurosystem applies the currency intervention in close cooperation with the relevant non-euro area national banks. The currency exchange transactions allow stabilising prices, since a lower currency valuation may help improve exports and drive economic growth, while a higher currency valuation cause exports to be less competitive. -

Communication from the Commission — Corresponding Values of The

3.12.2011 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 353/1 II (Information) INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION Corresponding values of the thresholds of Directives 2004/17/EC, 2004/18/EC and 2009/81/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (2011/C 353/01) The corresponding values in the national currencies other than euros of the thresholds of Directives 2004/17/EC ( 1 ), 2004/18/EC ( 2) and 2009/81/EC ( 3 ) are the following: EUR 80 000 BGN New Bulgarian lev 156 464 CZK Czech koruna 2 004 240 DKK Danish krone 595 928 GBP Pound sterling 69 574 HUF Hungarian forint 21 824 000 LTL Lithuanian litas 276 224 LVL Latvian lats 56 648 PLN New Polish zloty 321 568 RON New Romanian leu 337 232 SEK Swedish krona 759 016 EUR 130 000 BGN New Bulgarian lev 254 254 CZK Czech koruna 3 256 890 DKK Danish krone 968 383 GBP Pound sterling 113 057 HUF Hungarian forint 35 464 000 LTL Lithuanian litas 448 864 LVL Latvian lats 92 053 PLN New Polish zloty 522 548 ( 1 ) OJ L 134, 30.4.2004, p. 1. ( 2 ) OJ L 134, 30.4.2004, p. 114. ( 3 ) OJ L 216, 20.8.2009, p. 76. C 353/2 EN Official Journal of the European Union 3.12.2011 RON New Romanian leu 548 002 SEK Swedish krona 1 233 401 EUR 200 000 BGN New Bulgarian lev 391 160 CZK Czech koruna 5 010 600 DKK Danish krone 1 489 820 GBP Pound sterling 173 934 HUF Hungarian forint 54 560 000 LTL Lithuanian litas 690 560 LVL Latvian lats 141 620 PLN New Polish zloty 803 920 RON New Romanian leu 843 080 SEK Swedish krona -

Currencies Operating Under New Wire Payment Process

Currencies currently operating under the new wire payment process Curr en cy Bank Name Africa Code Kenyan Shilling KES Stanbic Bank, Nairobi Namibian Dollar NAD Standard Bank Namibia, Ltd, Windhoek South African Rand ZAR Standard Bank of South Africa, Johannesburg Curr en cy Bank Name Asia Code Hong Kong Dollar HKD Standard Chartered Bank, Hong Kong Indian Rupee** INR ICICI Bank, Local Western Union Agent Locations Japanese Yen JPY Standard Chartered Bank, Tokyo Singapore Dollar SGD The Bank of New York Mellon Thai Bhat THB HSBC Bank, Bangkok Curr en cy Australia / Oceania Code Bank Name Australian Dollar AUD HSBC Bank, Sydney Fiji Dollar FJD Westpac Banking Corporation, Suva New Zealand Dollar NZD Westpac Banking Corporation, Wellington Samoan Tala WST Westpac Bank Samoa Limited, Apia Tahitian (Central Polynesian) Franc XPF Banque de Polynesie, Papeete Vanuatu Vatu VUV Westpac Banking Corporation, Port Vila Curr en cy Bank Name Europe Code British Pound GBP HSBC Bank PLC, London Czech Republic Koruna CZK Ceskoslovenska Obchodni Banka Danish Krone DKK Danske Bank, Copenhagen Euro (Main)*** EUR HSBC Bank PLC, London Hungarian Forint HUF HSBC Bank PLC, London Latvian Lats LVL HSBC Bank PLC, London Lithuanian Litas LTL HSBC Bank PLC, London Norwegian Krone NOK Den Norske Bank, Oslo Polish Zloty PLN ING Bank, Poland Swedish Krona SEK Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB), Stockholm Swiss Fran c CHF Credit Suisse, Zurich Curr en cy Bank Name Middle East Code Bahrain Dinar BHD HSBC Bank PLC, London Israeli Shekel ILS HSBC Bank PLC, London Jordanian JOD HSBC Bank PLC, London Dinar Kuwaiti KWD HSBC Bank PLC, London Dinar Omani OMR HSBC Bank PLC, London Rial Qatari Rial QAR HSBC Bank PLC, London Turkish Lira TRY HSBC Bank PLC, London United Arab Emirates Dirham AED HSBC Bank PLC, London Curr en cy Bank Name North America Code Canadian Dollar CAD Royal Bank of Canada, Montreal Mexican Peso MXN HSBC Bank, Mexico United States Dollar (Main) USD Bank of New York Mellon, New York * Students in the Guangdong Province can utlize CITIC Bank in person. -

Euro Crash Risk

No. 524 Roman Kräussl, Thorsten Lehnert, Sigita Senulyte Euro Crash Risk The CFS Working Paper Series presents ongoing research on selected topics in the fields of money, banking and finance. The papers are circulated to encourage discussion and comment. Any opinions expressed in CFS Working Papers are those of the author(s) and not of the CFS. The Center for Financial Studies, located in Goethe University Frankfurt’s House of Finance, conducts independent and internationally oriented research in important areas of Finance. It serves as a forum for dialogue between academia, policy-making institutions and the financial industry. It offers a platform for top-level fundamental research as well as applied research relevant for the financial sector in Europe. CFS is funded by the non-profit-organization Gesellschaft für Kapitalmarktforschung e.V. (GfK). Established in 1967 and closely affiliated with the University of Frankfurt, it provides a strong link between the financial community and academia. GfK members comprise major players in Germany’s financial industry. The funding institutions do not give prior review to CFS publications, nor do they necessarily share the views expressed therein. Euro Crash Risk Roman Krussl, Thorsten Lehnert* and Sigita Senulyt Luxembourg School of Finance, University of Luxembourg August 2015 Abstract We identify crucial events during the European sovereign debt crisis and investigate their impact on the euro currency. In particular, we analyze how specific announcements related to vulnerable Eurozone member states, European Central Bank (ECB) actions, and credit rating downgrades affect the value and the crash risk of the euro. We proxy the value changes of the euro by its abnormal foreign exchange (FX) rate returns with respect to 35 currencies.