RURAL ROADS March 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PASER Manual Asphalt Roads

Pavement Surface Evaluation and Rating PASER ManualAsphalt Roads RATING 10 RATING 7 RATING 4 RATING PASERAsphalt Roads 1 Contents Transportation Pavement Surface Evaluation and Rating (PASER) Manuals Asphalt PASER Manual, 2002, 28 pp. Introduction 2 Information Center Brick and Block PASER Manual, 2001, 8 pp. Asphalt pavement distress 3 Concrete PASER Manual, 2002, 28 pp. Publications Evaluation 4 Gravel PASER Manual, 2002, 20 pp. Surface defects 4 Sealcoat PASER Manual, 2000, 16 pp. Surface deformation 5 Unimproved Roads PASER Manual, 2001, 12 pp. Cracking 7 Drainage Manual Patches and potholes 12 Local Road Assessment and Improvement, 2000, 16 pp. Rating pavement surface condition 14 SAFER Manual Rating system 15 Safety Evaluation for Roadways, 1996, 40 pp. Rating 10 & 9 – Excellent 16 Flagger’s Handbook (pocket-sized guide), 1998, 22 pp. Rating 8 – Very Good 17 Work Zone Safety, Guidelines for Construction, Maintenance, Rating 7 – Good 18 and Utility Operations, (pocket-sized guide), 1999, 55 pp. Rating 6 – Good 19 Wisconsin Transportation Bulletins Rating 5 – Fair 20 #1 Understanding and Using Asphalt Rating 4 – Fair 21 #2 How Vehicle Loads Affect Pavement Performance Rating 3 – Poor 22 #3 LCC—Life Cycle Cost Analysis Rating 2 – Very Poor 23 #4 Road Drainage Rating 1 – Failed 25 #5 Gravel Roads Practical advice on rating roads 26 #6 Using Salt and Sand for Winter Road Maintenance #7 Signing for Local Roads #8 Using Weight Limits to Protect Local Roads #9 Pavement Markings #10 Seal Coating and Other Asphalt Surface Treatments #11 Compaction Improves Pavement Performance #12 Roadway Safety and Guardrail #13 Dust Control on Unpaved Roads #14 Mailbox Safety #15 Culverts-Proper Use and Installation This manual is intended to assist local officials in understanding and #16 Geotextiles in Road Construction/Maintenance and Erosion Control rating the surface condition of asphalt pavement. -

Experimental Study on the Dynamics of Washboard Road on Various Surfaces

Experimental Study on the Dynamics of Washboard Road on Various Surfaces Teeranai SRIMAHACHOTA Candidate for the Degree of Master’s Degree Supervisor: Prof. Shunji KANIE Division of Engineering and Policy for Sustainable Environment Introduction Washboarding is the spontaneous formation of transverse ripple on dirt road. It is usually found on unpaved heavy- traffic road under dry weather condition. Driving over washboard road may increase risk of traffic accident since ripples reduce the contact area of the wheel to the road. Mitigating washboard road has long been a challenge for the road maintenance [1]. In addition, spontaneous formation of ripple pattern similar to washboarding can be found on other physical system; for examples, rail corrugation [2, 3], sand dune [4], lubricated disks [5], and periodic ripples on snow covered road [6]. The mechanism of washboarding was first studied in 1962 Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the experimental apparatus. by Mather [7], and he concluded that it caused by the (a) top view of the self-rotating track showing several ripples bouncing motion of the wheel excided by random formed on the track. (b) diagram of the seesaw-shaped perturbation on road surface. Recent studies have shown that oscillator. washboard road can be formed using rolling wheel [8] and inclined plowed dragged on a granular surface [9, 10]. measure original height of the surface. Then we place the Washboarding can be described by theoretical models which oscillator to touch gently on the flat surface. The oscillator is determine the effect of lift and drag forces to the time in the balance of force so that almost no compression force variation of surface geometry. -

The Road Inventory of Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge Knotts Island, NC

The Road Inventory of Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge Knotts Island, NC Prepared By: Federal Highway Administration Central Federal Lands Highway Division October, 2010 Report Generated: 10/05/2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 - 1 II. SUMMARY INFORMATION Summaries by Condition, Surface Type and Functional Class 2 - 1 III. REFUGE ROUTE LOCATION MAPS 3 - 1 IV. ROUTE IDENTIFICATION LIST 4 - 1 V. ROUTE CONDITION RATING SHEETS 5 - 1 VI. PARKING LOT CONDITION RATING SHEETS 6 - 1 VII. BRIDGE INVENTORY INFORMATION 7 - 1 VIII. PHOTOGRAPHIC SHEETS 8 - 1 IX. ACCIDENT SUMMARY 9 - 1 APPENDIX Funcitonal Classification Table i Description of Rating System ii INTRODUCTION The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (Public Law 105-178) created the Refuge Roads Program. Refuge roads are those public roads that provide access to or within a unit of the National Wildlife Refuge System and for which title and maintenance responsibility is vested in the United States Government. Funds from the Highway Trust Fund are available for refuge roads and can be used by the station to pay the cost of: (a) Maintenance and improvements of refuge roads. (b) Maintenance and improvements of: (1) Adjacent vehicle parking areas (2) Provision for pedestrians and bicycles and (3) Construction and reconstruction of roadside rest areas that are located in or adjacent to wildlife refuges (c) Administrative costs associated with such maintenance and improvements. The funds available for refuge roads are to be disbursed based on the relative needs of the various refuges in the National Wildlife Refuge System, and taking into consideration: (a) The comprehensive conservation plan for each refuge; (b) The need for access as identified through land use planning; and (c) The impact of land use planning on existing transportation facilities. -

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION City of Lubbock Street Department

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction • Brief Summary of the Pavement Preservation Strategy and Assessment of Current Conditions Pavement Preservation Overview • What is Pavement Preservation? iVIaintenance Strategies and Practices • strategies for Asphalt Paving • Strategies for Concrete Paving • Strategies for Brick Paving Test Sections of Streets • List of Test Sections • Test Sections Evaluations PAVER • Overview of MicroPAVER • Sample Inspections Sheets • Sample Report Sheets Pavement Distresses • Paved Asphalt Distresses • Paved Concrete Distresses • Paved Brick Distresses Paver Aids in Implementing GASB 34 • PAVER Aids in Implementing GASB 34 • Current Estimated Value of City of Lubbock Streets • Current Estimated Value of City of Lubbock Streets by Council District • Articles briefly explaining GASB 34 Glossary • Pavement Preservation Glossary of Terms Appendix • November 1983, APWA Reporter Article on PAVER • Asset Management and Innovative Finance Page 1 of 1 Pavement Preservation Strategies Table of Contents INTRODUCTION City of Lubbock street Department August 22, 2003 Brief Summary of the Pavement Preservation Strategy And Assessment of Current Conditions The City of Lubbock has over 2600 lane-miles of paved streets with a replacement value of approximately $250,000,000. Street Department is charged with the responsibility of effectively preserving this extensive portion of the City's infrastructure. Although the overall pavement preservation strategy has many aspects, the following is a brief summary of the typical scenario. A. History: The City of Lubbock since 1984 has been a subscriber to the American Public Works Association (APWA) PAVER Project. This computerized street maintenance program, as well as an associated Microsoft Access database program, provides such information on each block of paved street as; 1. -

Preliminary Design Report

Guemes Island Ferry Replacement Preliminary Design Report PREPARED FOR: BY: Jeffrey M. Rider, PE Skagit County Public Works PROJECT ENGINEER Mount Vernon, Washington CHECKED: William L. Moon III, PE PROJECT MANAGER APPROVED: Matthew S. Miller, PE PRINCIPAL-IN-CHARGE DOC: REV: FILE: DATE: 17097.02-053-02 - 17097.02 12 February 2021 References 1. Guemes Island Ferry Replacement, Concept Design Report, Glosten Inc., Report No. 17097- 053-01, Rev -, 11 December 2017. 2. Guemes Island Ferry Replacement, Vessel Capacity Study, Glosten Inc., Report No. 17097- 000-01, Rev -, 20 October 2017. 3. Guemes Island Ferry Replacement, Transportation System Assessment, Glosten Inc., Report No. 17097-000-02, Rev -, 14 December 2017. 4. Kristensen, H. O. H. "The manoeuvrability of double-ended ferries: design considerations, construction and service experience." Proceedings of the International Conference on Ship Motions & Manoeuvrability, RINA, London, UK, Paper: P1998-5 Proceedings. 1998. 5. Guemes Island Ferry Replacement, Preliminary Vessel Cost Estimate, Glosten Inc., Report No. 17097.02-043-03. 6. Guemes Island Ferry Replacement, Preliminary Vessel Cost Estimate, Glosten Inc., Report No. 17097.02-043-03. 7. Guemes Island Ferry Replacement, Preliminary Shoreside Cost Estimate, Glosten Inc., Report No. 17097.02-043-04. Summary This report describes the preliminary vessel design developed to replace the M/V Guemes, currently operating as a vehicle and passenger ferry between Anacortes and Guemes Island, Washington. The following drawings and reports -

Guidelines for Mine Haul Road Design

GGUUIIDDEELLIINNEESS FFOORR MMIINNEE HHAAUULL RROOAADD DDEESSIIGGNN Dwayne D. Tannant & Bruce Regensburg 2001 Guidelines for Mine Haul Road Design Table of Contents 1 SURVEY OF HAUL TRUCKS & ROADS FOR SURFACE MINES ............................... 1 1.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Haul Trucks and Construction/Maintenance Equipment ................................................. 1 1.3 Haul Road Length ............................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Haul Road Geometry ....................................................................................................... 4 1.5 Haul Road Construction Materials .................................................................................. 6 1.6 Symptoms and Causes of Haul Road Deterioration ........................................................ 6 1.7 Haul Road Maintenance .................................................................................................. 7 1.8 Evolution of Haul Road Design at Syncrude ................................................................... 8 1.8.1 Layer Thickness .................................................................................................................. 9 1.8.2 Haul Road Geometry .......................................................................................................... 9 1.8.3 Construction Techniques ................................................................................................. -

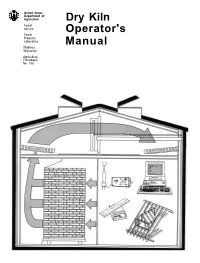

Dry Kiln Operator's Manual

United States Department of Agriculture Dry Kiln Forest Service Operator's Forest Products Laboratory Manual Madison, Wisconsin Agriculture Handbook No. 188 Dry Kiln Operator’s Manual Edited by William T. Simpson, Research Forest Products Technologist United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory 1 Madison, Wisconsin Revised August 1991 Agriculture Handbook 188 1The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION, Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides aand pesticide containers. Preface Acknowledgments The purpose of this manual is to describe both the ba- Many people helped in the revision. We visited many sic and practical aspects of kiln drying lumber. The mills to make sure we understood current and develop- manual is intended for several types of audiences. ing kiln-drying technology as practiced in industry, and First and foremost, it is a practical guide for the kiln we thank all the people who allowed us to visit. Pro- operator-a reference manual to turn to when questions fessor John L. Hill of the University of New Hampshire arise. It is also intended for mill managers, so that they provided the background for the section of chapter 6 can see the importance and complexity of lumber dry- on the statistical basis for kiln samples. -

Residential Concrete Tips

W hy C oncrete? Choosing concrete for driveways, sidewalks and patios enhances the appearance and value of your home and requires very little maintenance. The most common materials used in home exterior flatwork are concrete and asphalt. At first glance, they seem quite similar. Both materials appear to give a smooth, solid finish. The similarities end there. Concrete Asphalt Longer product lifecycle (30+ years) means fewer repairs Requires regular sealing to keep the pavement flexible, or replacement. increasing the overall cost of pavement ownership. Concrete is environmentally friendly. Its production and “Hot mix” asphalt production and placement requires tem- placement are not energy intensive. peratures that exceed 200 – 250 degrees F. Concrete pavements are “cooler”; their light color reduces Darker colored asphalt pavement absorb the heat and pro- heat retention. duce greater surface and ambient temperatures. Lighter colored concrete pavements require less lighting to Darker colored asphalt pavement may require 33% more illuminate a given area. lighting for a given area than concrete. Concrete is considered a “rigid” pavement and can evenly Asphalt is considered a “flexible” pavement and is subject carry heavy loads (trucks, boats, etc.). to defects such as rutting and washboarding under heavy traffic. Resistant to oils and other petroleum-based liquids. Easily deteriorated by gas, oil, anti-freeze and other com- Concrete can easily be constructed in a variety of shapes mon chemicals. and colors. Asphalt does not offer a variety of creative construction RESIDENTIAL options. Architectural Concrete CONCRETE Homeowners also have a variety of color and texture options available to them by staining or stamping concrete. -

Performance of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement on Unpaved Roads (MPC-13-251)

Performance of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement on Unpaved Roads Scott Koch George Huntington, P.E. Khaled Ksaibati, PhD., P.E. Wyoming Technology Transfer Center University of Wyoming Laramie, Wyoming May 2013 Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank all the employees of Laramie, Johnson and Sweetwater counties who assisted with this project. Without their expertise, assistance, and cooperation, this study could not have been conducted. Thanks to the Desert Mountain Corporation for their expertise and assistance on the Sweetwater County sections. We would also like to thank the Wyoming Department of Transportation for their support of this project. Finally, we would like to thank Mary Harman, Bart Evans, Josh Jones, Burt Andreen, Jonathan Zumwalt, and Harry Rocheville for their work on this project. Disclaimer The contents of this report reflect the work of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented. Mention of specific products is for informational purposes only and does not constitute any endorsement. This document does not constitute any policy of or endorsement by the Mountain-Plains Consortium or the University of Wyoming.This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Mountain-Plains Consortium in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. North Dakota State University does not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, gender expression/identity, genetic information, marital status, national origin, public assistance status, sex, sexual orientation, status as a U.S. veteran., race or religion. Direct inquiries to the Vice President for Equity, Diversity and Global Outreach, 205 Old Main, (701) 231-7708. -

Implementing a Pavement Management System PASER Based – City of Omaha, NE Introductions

Implementing a Pavement Management System PASER Based – City of Omaha, NE Introductions JESS HASTINGS, PE TIM O’BRYAN, PE Project Manager Senior Project Manager 10 Years of Experience 30 Years of Experience Introduction Full-Service Consulting Firm • Transportation Focus • Value Engineering and Planning Background • Asset Management Pavement Management Experience • Cities, Counties, DOT’s and Airports • PCI Evaluations • 29 Offices in 16 States • PASER Evaluations • +600 Professionals City of Omaha Case Study City of Omaha Pavement Management Background • No Formal Process • Lack of Documentation • “Worst First” and Complaint Driven Approach • Re-active not Pro-active (No concrete maintenance) • Lane Miles Increase – Budget Stagnate/Decrease What do we do???? Develop a Formal Pavement Management System Why Pavement Management? • Save maintenance and reconstruction costs • Provides systematic method of maintaining network • Increase longevity of pavement • Assists with prioritization of maintenance and repair work • Integrates scheduling and different department efforts • Assist decision-makers with budgets • Improve effectiveness of resources spent on network Why Pavement Management? • Pavement does not deteriorate in a linear fashion Age of Pavement Why Pavement Management? • Increase Pavement Longevity with Routine Maintenance Age of Pavement Why Pavement Management? Step 1 – Define Network City of Omaha, Nebraska • Approximately 4,600 lane miles of roadway Roadway Classification Lane miles • Major and Minor Arterials ---- 1175 • Collector -

Camp Road Maintenance Manual

GRAVEL ROAD MAINTENANCE MANUAL A Guide for Landowners on Camp and Other Gravel Roads Kennebec County Maine Department of Soil and Water Environmental Protection Bureaus of Land Conservation District Resources and Water Quality April 2016 For the purposes of this manual, the terms “gravel road” and “camp road” are used interchangeably and are used to describe private and public roads that are typically narrow and unpaved. - TABLE OF CONTENTS - ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I INTRODUCTION 1 A Little History on Camp Roads 1 Some Questions and Answers 3 TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE 7 Road Surface Problems 7 Culvert Problems 9 Ditch Problems 10 UNDERSTANDING THE BASICS 11 Soil Erosion 11 Factors Linked to Erosion 12 Water and Your Road 13 Surface Water 14 Groundwater 14 Erosion Control Principles 15 Work with Nature 17 Where to Drain to: Vegetated Buffers 17 Types of Buffers 18 How to Have an Effective Buffer 18 Buffers: Cost-Effective, Low Maintenance, and Good for the Lake 19 CAMP ROAD MAINTENANCE 20 Road Surface 20 Road Level 20 Road Materials 21 Road Material Composition 22 Alternative Road Surfacing Materials 24 Geotextiles as Road Base 24 Reclaimed Pavement/Recycled Asphalt (Reclaim) 26 Pavement 27 Other Alternative Surface Materials 27 Grading 28 Crowning and Super-Elevating 30 Alternative Equipment 33 Steel Tine Rake 33 Frontrunner Device 34 Dust Control 35 Winter Maintenance 37 Road Drainage 39 Ditches 39 Ditch Shape 40 Ditch Size and Depth 42 Ditch Erosion and Stabilization 43 Erosion in Ditches 43 Seeding and Mulching 44 Erosion Control Mix 46 Erosion -

Phase II—Demonstration Project

R. J Morgan, V.R. Schaefer, R. S. Sharma Determination and Evaluation of Alternative Methods for Managing and Controlling Highway-Related Dust Phase II—Demonstration Project June 2005 Sponsored by the Iowa Department of Transportation Highway Division and the Iowa Highway Research Board Iowa DOT Project TR-506 Final Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering The opinions, findings and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Iowa Department of Transportation. The sponsor does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade and manufacturers names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of this document. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. IHRB Project TR-506 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Determination and Evaluation of Alternative Methods for Managing and June 2005 Controlling Highway-Related Dust 6. Performing Organization Code Phase II—Demonstration Project 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Ryan J Morgan, Vernon R. Schaefer, Radhey S. Sharma 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering Iowa State University 11. Contract or Grant No. 394 Town Engineering Building Ames, IA 50011-3232 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Iowa Highway Research Board Final Report Iowa Department of Transportation 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 800 Lincoln Way Ames, IA 50010 15. Supplementary Notes Visit www.ccee.iastate.edu for color PDF files of this and other research reports.