Integrating Sustainability Into Project Management Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Benchmarking Can Support the Selection, Planning and Delivery of Nuclear Decommissioning Projects

This is a repository copy of How benchmarking can support the selection, planning and delivery of nuclear decommissioning projects. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/117185/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Invernizzi, DC, Locatelli, G orcid.org/0000-0001-9986-2249 and Brookes, NJ (2017) How benchmarking can support the selection, planning and delivery of nuclear decommissioning projects. Progress in Nuclear Energy, 99. pp. 155-164. ISSN 0149-1970 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2017.05.002 (c) 2017, Elsevier Ltd. This manuscript version is made available under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Please cite this as Diletta Colette Invernizzi, Giorgio Locatelli, Naomi J. Brookes, How benchmarking can support the selection, planning and delivery of nuclear decommissioning projects, Progress in Nuclear Energy, Volume 99, August 2017, Pages 155-164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2017.05.002. -

Executive AC Workshop Meeting Summary and Handouts

LOUISIANA STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION PLAN UPDATE EXECUTIVE ADVISORY COUNCIL WORKSHOP SUMMARY March 11, 2014 8:30AM to 5:00PM LA DOTD Headquarters, Baton Rouge, LA Last Name First Name Affiliation Advisory Council Members Accardo, Jr. Joe Ports & Waterways AC Chair (Ports Association of LA) Blackmon Carmack Freight Rail AC Chair (Louisiana Railroads Association) Decker Dennis Regional Planning Officials AC Chair (LA DOTD) Latino Vince State Hwy Operations & Maintenance AC Chair (LA DOTD) Kalivoda (Chair) Eric LA DOTD Bridges Michael LA DOTD Gallien Kirk LA DOTD Jones Phil LA DOTD Picard Toby LA DOTD Reed Kevin LA DOTD Rogers Kent LA DOTD Savoie Richard LA DOTD Williams Janice LA DOTD Other Attendees Gautreaux Cathy [sub for Reggie Dupre, Trucking AC Chair] Slayter David [sub for Heath Allen, Aviation AC Chair] Broussard Dan LA DOTD Romeo Robin LA DOTD Sholmire Dawn LA DOTD Vary (Facilitator) Don CDM Smith Babineaux Butch CDM Smith Goodin Krista CDM Smith Nelson Gordon Fenstermaker Buckner Brandon FHWA Bondzie Chandra FHWA PURPOSE The purpose of this work session was to finalize components of the Statewide Transportation Plan prior to presentation to the Policy Committee. Note: This meeting summary is a compilation of the input received from the Advisory Council members and reflects the views expressed. HANDOUTS Agenda Vision, Goals, Objectives, and Performance Measures Recommendations by Advisory Council Megaprojects Budget Line Items Executive Advisory Council Meeting Summary Page 1 of 2 MEETING SUMMARY Eric Kalivoda, Executive AC Chair, welcomed the group and reminded the members their role on the Executive Advisory Council. He then led a round of introductions. Don Vary with CDM Smith gave a brief presentation summarizing key parts of the Statewide Transportation Plan. -

L'évaluation Des Impacts Sociaux: Vers Un Développement Viable?

L'évaluation des impacts sociaux: vers un développement viable? sous la direction de CHRISTIANE GAGNON Collection développement régional GROUPE DE RECHERCHE ET D'INTERVENTION RÉGIONALES Coordination à l'édition: Suzanne Tremblay Correction linguistique: Nicole Fradette Édition finale: Esther Cloutier Université du Québec à Chicoutimi Dépôt légal — 2e trimestre 1995 Bibliothèque du Canada Bibliothèque du Québec ISBN: 2-920730-32-0 Distribution: GR3K. 555, boul. de l'Université Chicoutimi (Québec) G7H2B1 Tél.: (418)545-5534 TABLE DES MATIERES AVANT-PROPOS, INTRODUCTION: La participation des communautés à l'évaluation des impacts sociaux: une pratique incontournable pour asseoir un développement viable Christiane GAGNON, Université du Québec à Chicouîimi, Québec PARTIE I: HISTORIQUE, DIFFICULTES, RÔLE ET PERSPECTIVES DE L'ÉVALUA- TION DES IMPACTS SOCIAUX In praise of SIA. A personal review of the field of social impact assessment: feasibility, justification, history, methods and issues Kurt FINSTERBUSCH, University of Maryland at College Park, USA 13 PARTIE II: ÉTUDES DE CAS ET CONSIDÉ- RATIONS MÉTHODOLOGIQUES The need for retrospective impact assessment: the megaprojects example Peter BOOTHROYD, Center for Human Settlements, University of British Columbia, British Columbia 43 Evaluation ex post des impacts sociaux du mégaprojet d'aluminerie sur la communauté laterroise Christiane GAGNON, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, Québec 65 Social impact assessment, community and environmental sustainability: a comparative analysis of two australian -

7. Megaprojects

7. Megaprojects The Plan is intended to foster long-term economic growth and enhance the quality of life for Louisiana citizens by identifying efficient and effective investments and policies. As part of this effort, the Plan identifies major transportation improvements or “megaprojects” that have been proposed throughout the state. For the purposes of the Plan, a megaproject is a very expensive or large scale transportation improvement that would have a regional or statewide impact and would require special funding outside of normal DOTD funding mechanisms. A transportation improvement included as a megaproject in the Plan may be eligible for further study and possibly implementation, should additional state or federal funding become available. The list of megaprojects and their prioritization are further described below and included fully in Appendix F. 7.1 Highlights 113 Total Megaprojects • RPOs were presented with 113 megaprojects for Plan consideration. Priority A Megaprojects • Priority A has 20 megaprojects for a total of $4.8 billion ($3.7 billion from DOTD). These can be funded under Scenarios 3 or 4, as outlined in Chapter 5. Priorty B Megaprojects • Priority B has 19 megaprojects for a total of $5.8 billion ($3 billion from DOTD). These can only be funded under Scenario 4, as outlined in Chapter 5. 7.2 Megaproject Development A key component of the Plan is selecting the right mix of projects and project types that best achieve intended outcomes, goals, and objectives. Transportation agencies must balance the requirements of sustaining their existing system pavements and bridges against “modernization” improvements (safety, wider lanes, ITS) versus expansion investments (new construction, additional capacity). -

Qnbfs.Com.Qa [email protected] [email protected]

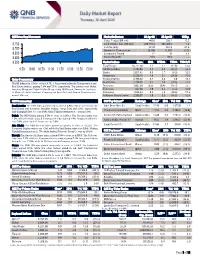

QSE Intra-Day Movement Market Indicators 29 Apr 20 28 Apr 20 %Chg. Value Traded (QR mn) 448.8 396.1 13.3 8,750 Exch. Market Cap. (QR mn) 490,773.4 483,580.5 1.5 Volume (mn) 421.0 251.2 67.6 8,700 Number of Transactions 10,760 11,087 (2.9) 8,650 Companies Traded 47 45 4.4 Market Breadth 37:9 35:9 – 8,600 8,550 Market Indices Close 1D% WTD% YTD% TTM P/E Total Return 16,727.50 1.2 2.7 (12.8) 13.6 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 All Share Index 2,705.06 1.1 2.6 (12.7) 14.2 Banks 3,857.41 0.8 1.7 (8.6) 12.5 Industrials 2,228.16 1.8 3.1 (24.0) 17.6 Qatar Commentary Transportation 2,708.52 3.4 9.3 6.0 13.1 The QE Index rose 1.2% to close at 8,701.1. Gains were led by the Transportation and Real Estate 1,278.39 3.1 7.3 (18.3) 11.2 Real Estate indices, gaining 3.4% and 3.1%, respectively. Top gainers were Qatari Insurance 2,003.50 (0.5) (0.4) (26.7) 33.7 Investors Group and Ezdan Holding Group, rising 10.0% each. Among the top losers, Telecoms 847.48 1.0 4.3 (5.3) 14.0 Al Khaleej Takaful Insurance Company and Qatar National Cement Company were Consumer 7,042.34 0.3 1.9 (18.6) 17.4 down 1.6% each. -

China's 2010 Work Forum on Tibet: a Turn Towards Meeting Basic Human Needs?

CHINA'S 2010 WORK FORUM ON TIBET: A TURN TOWARDS MEETING BASIC HUMAN NEEDS? Gabriel Lafitte February 2010 [email protected] PRELUDE TO A NEW APPROACH: POLICY EXHAUSTION Official Chinese policy on Tibet has long had two strands -on one hand development, on the other stability/security. Few seem to notice they are contradictory, giving with one hand, taking with the other; creating opportunities only to restrict access to them, to those who can be trusted, who in Tibet almost always are Chinese immigrants. The internal contradictions of promoting growth while restricting Tibetan agency inevitably lead to Tibetans feeling excluded, while the promised growth benefits only the Chinese immigrants, from top officials down to Sichuanese expeasant building labourers. This contradiction is at the root of Tibetan frustrations, and is compounded by the internal contradiction of the propaganda work of the new elite in Tibet. The security state China has built in Tibet is run by a new elite class of cadres that peddles a narrative which follows a predictable trajectory, a cycle which repeats over the years. Tibetans and their friends around the world are very familiar with one part of this operatic cycle, in which the splittist Dalai clique is denounced in harsh, lurid language. This never fails to attract more money from Beijing to strengthen the security state. Then the elite gradually shifts to assuring Beijing and anyone else listening, that the Tibetan masses generally are patriotic, and support the party and want nothing to do with the tiny but ever present splittist enemy within. Eventually, through endless repetition the party elite in Tibet and in Beijing come to believe their own propaganda narrative. -

REDESIGNING AREA/COUNTRY STUDIES Hans Kuijper

COMPARATIVE COUNTRY STUDIES REDESIGNING AREA/COUNTRY STUDIES Hans Kuijper Area/country studies like Turkology, Iranology, Indology, Sinology, Koreanol- ogy and Japanology are fundamentally flawed. They have an explanandum, but do not have a distinctive explanans. On the one hand, the practitioners of this kind of study tacitly claim to be knowledgeable about anything concerning the area or country of their interest (after all, Sinology is the study of China, just as sociology is the study of society). On the other hand, they reluctantly admit that it is impossible to be an expert on, say, the economy, polity and society of the country, given the prodigious amount of information available about these domains, the conflicting schools of thought, and the increasing awareness of the complexity of the world. The premises of this paper, meant to be also foun- dational to IR/Global Studies, are: (a) proper understanding of a country is only possible if a truly interdisciplinary approach is taken, and (b) the insights of computer, network and complex systems scientists could be profitably used in doing so. Rethinking area/country studies in a global context, the author concludes that the subject, being of great importance for international peace and security, should be high on the agenda of the higher-education discussion. Keywords: area/country studies, scientific collaboration, computer science, systems science, higher education. Introduction The School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), in London, the Leiden University Institute for Area Studies (LIAS), the National Institute for Oriental Languages and Civilizations (INALCO), in Paris, the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), in Hamburg, the Institute of Oriental Studies (IOS) of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), in Moscow, and the Japan Consortium for Area Studies (JCAS), in Tokyo, are some of the institutions solely devoted to area/country studies. -

Al Rayan Qatar Etf Interim Condensed Financial Statements

Economy & Business Thursday, April 30, 2020 09 Air traffic Qatar’s virus package, mega projects plunges 53% in March, take centre stage in OBG report says IATA AFP PARIS Tourism has been identified as one of the sectors of Qatar’s economy with high-growth potential WORLD air traffic suffered a massive drop of more than TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK covered from the economic half in March compared with DOHA impact of lower oil prices the same period last year in 2014-16 and the ongoing thanks to coronavirus-related Qatar’s bid to continue di- blockade suggest the coun- travel restrictions, the airline versifying its economy, while try is well placed to reach the industry’s trade body said introducing a QR75 billion longer-term goals outlined in Wednesday. ($20.6 billion) stimulus pack- its development plan, the Na- The 52.9 percent drop age to ease the impact of the tional Vision 2030.” when measured by total rev- Covid-19 pandemic, is ex- Jana Treeck, the Group’s enue per passenger kilome- plored in detail in a new report Managing Director for the tres “was the largest decline by the global research and ad- Middle East, agreed that while in recent history, reflecting visory firm Oxford Business the world currently faces un- the impact of government Group (OBG). precedented challenges from actions to slow the spread of The Report: Qatar 2020 the pandemic, Qatar’s efforts COVID-19”, said the Interna- shines a spotlight on the coun- to keep the fiscal balance in tional Air Transport Associa- try’s list of megaprojects, many surplus, while also channel- tion (IATA). -

Linkages in Mozambique

Demand and Opportunity Assessment and Analysis: Linkages in Mozambique Commissioned by Building Markets with ACIS Final Report prepared by Genesis Analytics and ICC Made possible through the generous support of the Skoll Foundation 31 January 2013 I C C Document Reference: Building Markets, Linkages, Final report Date: 31 January 2013 Contact Information Genesis Analytics (Pty) Ltd Office 3, 50 Sixth Road Hyde Park, 2196, Johannesburg South Africa Post to: PO Box 413431, Craighall, 2024 Johannesburg, South Africa Tel: +2711 994 7000 Fax: +2711 994 7099 www.genesis-analytics.com Authors Genesis Analytics ICC Contact Person Caitlin Smit [email protected] ii Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................ 1 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 7 1.1. Background to the study ........................................................................... 7 1.2. Methodology ............................................................................................. 8 1.3. Structure of the report ............................................................................. 10 2. MOZAMBICAN CONTEXT ..................................................................... 10 2.1. Growth profile .......................................................................................... 11 2.2. High priority investments in the extractives sector .................................. 13 2.3. Private sector profile -

Appendix A: Literature Review Summary Report Denali National Park and Preserve Existing Conditions Report Long Range Transportation Plan February 27, 2015

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Denali National Park and Preserve Long-Range Transportation Plan Appendix A: Literature Review Summary Report Denali National Park and Preserve Existing Conditions Report Long Range Transportation Plan February 27, 2015 1. Introduction This baseline conditions report summarizes the findings of a literature review conducted as part of the National Park Service’s (NPS) Denali National Park and Preserve (Denali NP&P) Long Range Transportation Plan (LRTP). This review will be used as the foundation for the LRTP’s baseline conditions chapter and consists of existing policies, guidelines, plans, conditions, and research related to the Denali NP&P’s transportation system. The vision for the Denali NP&P LRTP reflects the values expressed in the Park’s Foundation Statement and input received from Park staff and decision makers. This vision serves as the basis for the LRTP’s goals and objectives. The LRTP’s vision is: Protect intact, the globally significant Denali National Park and Preserve ecosystems, including their cultural, aesthetic, and wilderness values, and ensure appropriate access to opportunities for inspiration, education, research, recreation, and subsistence for this and future generations. 2. Literature Review Composition The literature review included 16 documents as well as notes from preliminary meetings conducted as part of the early stages of the LRTP process. Documents included in the literature review are: • Alaska Federal Lands Long Range Transportation Plan, 2012 • National -

L'évaluation Des Impacts Sociaux: Vers Un Développement Viable?

L'évaluation des impacts sociaux: vers un développement viable? sous la direction de CHRISTIANE GAGNON Collection développement régional GROUPE DE RECHERCHE ET D'INTERVENTION RÉGIONALES Coordination à l'édition: Suzanne Tremblay Correction linguistique: Nicole Fradeîte Édition finale: Esther Cloutier © Université du Québec à Chicoutimi Dépôt légal — 2e trimestre 1995 Bibliothèque du Canada Bibliothèque du Québec ISBN: 2-920730-32-0 Distribution: GRIR 555, boul. de l'Université Chicoutimi (Québec) G7H2B1 Tél.: (418)545-5534 TABLE DES MATIÈRES AVANT-PROPOS. INTRODUCTION: La participation des communautés à l'évaluation des impacts sociaux: une pratique incontournable pour asseoir un développement viable Christiane GAGNON, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, Québec PARTIE I: HISTORIQUE, DIFFICULTES, RÔLE ET PERSPECTIVES DE L'ÉVALUA- TION DES IMPACTS SOCIAUX In praise of SIA. A personal review of the field of social impact assessment: feasibility, justification, history, methods and issues Kurt FINSTERBUSCH, University of Maryland at College Park, US A 13 PARTIE II: ÉTUDES DE CAS ET CONSIDÉ- RATIONS MÉTHODOLOGIQUES The need for retrospective impact assessment: the megaprojects example Peter BOOTHROYD, Center for Human Settlements, University of British Columbia, British Columbia 43 Évaluation ex post des impacts sociaux du mégaprojet d'aluminerie sur la communauté laterroise Christiane GAGNON, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, Québec 65 Social impact assessment, community and environmental sustainability: a comparative analysis of two australian -

Identification of Key Supply Chain Elements for Megaprojects Success. International Research Network on Organizing by Projects (IRNOP) 2017, UTS Epress, Sydney

Published by CONFERENCE PAPER Project Identification of key supply chain elements for Management Research and megaprojects success Practice Mladen Radujković1*, Sandra Mišić2 1 Professor, Alma Mater Europea University, Slovenia. [email protected] 2 PhD candidate, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Economics and Business, Croatia. sandi.mišić@gmail.com *Corresponding author: Mladen Radujković, Europea University. [email protected] Name: International Research Network on Organizing by Projects (IRNOP) 2017 © 2018 by the author(s). This Location: Boston University, United States is an Open Access article Dates: 11-14 June 2017 distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Host Organisation: Metropolitan College at Boston University Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https:// DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/pmrp.irnop2017.5705 creativecommons.org/licenses/ Published: 07/06/2018 by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, Synopsis transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even Each megaproject influences life on the society level, so megaproject success or failure has commercially, provided the original work is properly cited another level dimension. In the past, the research community recognized the vital importance and states its license. of megaprojects for development of a country on the one hand. On the other hand, researched identified strong negative impact that schedule, time and cost overrun (not even mentioning Citation: Radujkovic, M. and Mišić, S. 2017. Identification of deceptions of public) of megaprojects might have for the development of a country. Recent key supply chain elements for studies in project management bring up supply chain conception as fertile component for megaprojects success.