Epitaph for a Musician: Rhoda Coghill As Pianist, Composer and Poet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miscellaneous Collection of the Terrell Family Records

MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTION OF THE TERRELL FAMILY RECORDS Publication No. 194 Compiled by Colonel Lynch Moore Terrell Ca 1910-1924 This publication has been retyped from the Original Terrell Book published ca 1910 and apparently represents a compilation of letters and papers accumulated over the years by two brothers and their cousin. They were: General William Henry Harrison Terrell 1827-1884 Indianapolis, Indiana. (His brother). Colonel Lynch Moore Terrell 1834-1924 Atlanta Georgia. Their cousin. Hon. Robert Williams Carroll 1820-1895 Cincinnati, Ohio. It is presumed that the Contents of this Book were assembled by Col. Lynch Moore Terrell some time between 1910 and 1924; after the death of Lynch’s brother and cousin. There are, among many other items, five interesting letters written to and from another cousin, Edwin Terrell 1848-1910 (Ambassador to Belgium 1889-1893), San Antonio, Texas. During this period when Edwin was Ambassador, Edwin became acquainted with Joseph Henry Terrell b 1863, Keswick, England. Joseph published in 1904 the best Tyrrell book on the English Terrells. It appears that Edwin and Joseph exchanged information on Terrell genealogy for both American and English Terrells. Publication No. 194 Published by the Terrell Society of America, Inc. Cairo GA USA 2001 I N D E X Introductory Note.. 1 Nomenclature-Origin and Personal Characteristics of the Terrells . 3 Physical Types and Personal Characteristics of the Terrells 7 List of Wills proved to the Name of Terrell Tyrrell)-(With its Variations in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury 1383-1700. 9 Extracts from the records of Caroline County and Cedar Creek, Virginia, Meetings, Society of Friends, respecting the Terrell Family . -

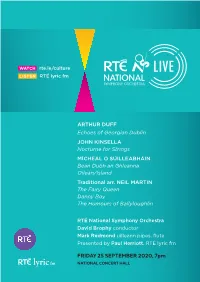

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

Intimations Surnames L

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames L This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames L Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage L’AMY / SCOTT 1863 Sylvester L’Amy, London, to Margaret Sinclair, 2nd daughter of John Scott, Finnart, Greenock, at St George’s, London on 6th May 1863.. see Margaret S. (Greenock Advertiser 9.5.1863) Marriage LACHLAN / 1891 Alexander McLeod to Lizzie, youngest daughter of late MCLEOD James Lachlan, at Arcade Hall, Greenock on 5th February 1891 (Greenock Telegraph 09.02.1891) Marriage LACHLAN / SLATER 1882 Peter, eldest son of John Slater, blacksmith to Mary, youngest daughter of William Lachlan formerly of Port Glasgow at 9 Plantation Place, Port Glasgow on 21.04.1882. (Greenock Telegraph 24.04.1882) see Mary L Death LACZUISKY 1869 Maximillian Maximillian Laczuisky died at 5 Clarence Street, Greenock on 26th December 1869. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

Scotch-Irish"

HON. JOHN C. LINEHAN. THE IRISH SCOTS 'SCOTCH-IRISH" AN HISTORICAL AND ETHNOLOGICAL MONOGRAPH, WITH SOME REFERENCE TO SCOTIA MAJOR AND SCOTIA MINOR TO WHICH IS ADDED A CHAPTER ON "HOW THE IRISH CAME AS BUILDERS OF THE NATION' By Hon. JOHN C LINEHAN State Insurance Commissioner of New Hampshire. Member, the New Hampshire Historical Society. Treasurer-General, American-Irish Historical Society. Late Department Commander, New Hampshire, Grand Army of the Republic. Many Years a Director of the Gettysburg Battlefield Association. CONCORD, N. H. THE AMERICAN-IRISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY 190?,, , , ,,, A WORD AT THE START. This monograph on TJic Irish Scots and The " Scotch- Irish" was originally prepared by me for The Granite Monthly, of Concord, N. H. It was published in that magazine in three successiv'e instalments which appeared, respectively, in the issues of January, February and March, 1888. With the exception of a few minor changes, the monograph is now reproduced as originally written. The paper here presented on How the Irish Came as Builders of The Natioji is based on articles contributed by me to the Boston Pilot in 1 890, and at other periods, and on an article contributed by me to the Boston Sunday Globe oi March 17, 1895. The Supplementary Facts and Comment, forming the conclusion of this publication, will be found of special interest and value in connection with the preceding sections of the work. John C. Linehan. Concord, N. H., July i, 1902. THE IRISH SCOTS AND THE "SCOTCH- IRISH." A STUDY of peculiar interest to all of New Hampshire birth and origin is the early history of those people, who, differing from the settlers around them, were first called Irish by their English neighbors, "Scotch-Irish" by some of their descendants, and later on "Scotch" by writers like Mr. -

Commemorative Program

A PLACE TO REMEMBER A MESSAGE FROM THE TASK FORCE CHAIR WELLAND CANAL FALLEN WORKERS MEMORIAL The Welland Canal is referred to as an engineering marvel that has stood the test of time. The great link between two Great Lakes was built by men who toiled in extreme conditions to connect Canada and the United States to the growing global economy. The Fallen Workers were fathers, brothers, uncles and friends and now, their efforts will never be forgotten. As Chair of the Welland Canal Fallen Workers Memorial, I would like to acknowledge the many people who have come together to build this important monument. Through the efforts and cooperation of various levels of government, labour, the marine and shipping industry, local media and community, and led by campaign chair Greg Wight, the Welland Canal Fallen Workers Memorial is a testament to the dedication of a small group of people who came together to ensure that those lives lost so long ago, finally received their long overdue memorial. Memory slowly fades with time, but now the Fallen Workers of the Fourth Welland Canal will be remembered for generations to come. Walter Sendzik Mayor, St. Catharines Task Force Chair Mayor Walter Sendzik @WSendzik City of St. Catharines @wsendzik /MayorSendzik www.mayorsendzik.ca Welland Canal WELLAND CANAL FALLEN WORKERS MEMORIAL PB 1 Fallen Workers Memorial A PLACE TO REMEMBER MONUMENT DÉDIÉ AUX OUVRIERS DÉCÉDÉS À LA CONSTRUCTION DU CANAL WELLAND Le canal Welland est reconnu comme un chef-d’œuvre d’ingénierie ayant résisté à l’épreuve du temps. Cette connexion a été bâtie par des hommes œuvrant dans des conditions extrêmes dans le but de rapprocher le Canada et les États-Unis de l’économie mondiale en croissance. -

Collections of Musicians' Letters in the UK and Ireland: a Scoping Study

Collections of musicians’ letters in the UK and Ireland: a scoping study Katharine Hogg, Rachel Milestone, Alexis Paterson, Rupert Ridgewell, Susi Woodhouse London December 2011 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all those who gave their time and expertise to make this scoping study possible. They include: the staff of organisations and individuals responding to the survey, staff at the BBC Written Archives, Oxford University Press, the London Symphony Orchestra, Cheltenham Festivals, Royal Festival Hall, Royal Academy of Music, Royal Society of Musicians, and those who kindly agreed to be interviewed on their use and perception of archives of letters. © Music Libraries Trust 2012 2 Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Rationale ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. The resource................................................................................................................................................ 5 2.2. Repositories ................................................................................................................................................ 5 2.3. Resource discovery...................................................................................................................................... 6 2.4. Data integration.......................................................................................................................................... -

2Ltuabus °E . .J2rl~E Com'qec1cions·

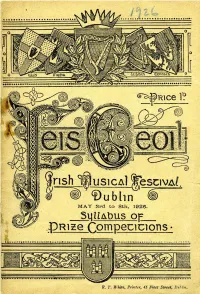

[ Q MAY .3rd to 8th, 1928. 2ltUAbus °E_. _ .J2Rl~e COm'QeC1CIOnS· 8.. 7', White, Printer, 4S Fleet Street, Dul·/:"u. " ( Notice to Competitors. OMPETITORS are requested to be careful that in the Feil Ceoil C Competitions, both Instrumental and Vocal, the specified edition is procured. Arrangements have been made by Mesers. Pigott &. Co., Ltd., THI~TIETH "3 Grafton Street, Dublin, to supply Candidates with the Test Piec~s in the correct editions at the lowe.t possible rates. F EIS C EO I L IRISH MUSICAL FESTIVAL. DUBLIN. MAY 3rd to 8th. 1926. SYLLABUS OF PRIZE COMPETITION S AND REPQRT OF MUSIC EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE. AND ALL THINOS MUSICAL. PIANOS ORGANS PLAYER - PIANOS GRAMOPHONES RECORDS VIOLINS Oreatest Facilities for Selection In Ireland. Service. of Expert Tuner. covera entire Country. Repair. by highly Skilled Craftsmen in the Firm'. Up-to-date Factory. DUBLIN : PUBLISHED BY THE FEIS CEOIL AS SOCIATION. 37 MOLESWORTH ST. 1926. GRAFTON ST. a SUFFOLK ST., DUBLIN. L ADd at CORK .. LIMUIC•• R. T. J-f/'lIite, Printer, 45 Fleet Street, Dtlblin, CONTENTS. ................................................ PAGE. 13 Adjudicators, List of. (1926) 6 It is earne.stiy ~equested that Competitions, Con~ltlons of . NOTICE. Constitution of Fels Ceoll 5 all Competitors should use Committees ... ... ... .. 4 Donors to Prize Fund (1925) ... .., 11 the correct and specified editions as stated Members of Association, List of (1925-26) 41 43 in Syllabus. •• •• :: .• Prize Winners, Calendar of .. Railway Travelling Facilities ... .. 11 Above are obtainable at Messrs. Report of Committee and Balance Sheets for 1925 34-40 McCullough's, 56 Dawson Street, Dublin. TEST PIECES AND PRIZES. -

Papers of Josephine Mcneill P234 Descriptive Catalogue UCD Archives

Papers of Josephine McNeill P234 Descriptive Catalogue UCD Archives archives @ucd.ie www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2009 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History iv CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and content vi System of arrangement vi CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access x Language x Finding Aid x DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note xi iii CONTEXT Biographical History McNEILL, Josephine (1895–1969), diplomat, was born 31 March 1895 in Fermoy, Co. Cork, daughter of James Ahearne, shopkeeper and hotelier, and Ellen Ahearne (née O’Brien). She was educated at Loretto Convent, Fermoy, and UCD (BA, H.Dip.Ed.). With a BA in French and German she began a teaching career, teaching at St Louis’ Convent, Kiltimagh, at the Ursuline Convent, Thurles, and at Scoil Íde, the female counterpart of St Enda’s, established by her friend Louise Gavan Duffy (qv). A fluent Irish-speaker with an interest in Irish language, music, and literature, she took an active part in the cultural side of the Irish independence movement. She was also a member of Cumann na mBan and in 1921 a member of the executive committee of that organisation. She was engaged to Pierce McCann, who died of influenza in Gloucester jail (March 1919). In 1923 she married James McNeill, Irish high commissioner in London 1923–8. Josephine McNeill took reluctantly to diplomatic life, but it never showed in public. Her charm and intelligence were immediately apparent, and in a period when Joseph Walshe (qv), the secretary of the Department of External Affairs, viewed married diplomats and diplomatic wives with disdain, McNeill was a noted hostess, both in London and later in Dublin, where James McNeill was governor general of the Irish Free State (1928–32). -

I Muse and Method in the Songs of Hamilton Harty

Muse and Method in the Songs of Hamilton Harty: Three Early Works, 1895–1913 Judith Carpenter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music The University of Sydney 2017 Sydney, Australia i This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my mother. To an Athlete Dying Young A. E. HOUSMAN The time you won your town the race We chaired you through the market-place; Man and boy stood cheering by, And home we brought you shoulder-high. Today, the road all runners come, Shoulder-high we bring you home, And set you at your threshold down, Townsman of a stiller town. Smart lad, to slip betimes away From fields where glory does not stay, And early though the laurel grows It withers quicker than the rose. Eyes the shady night has shut Cannot see the record cut, And silence sounds no worse than cheers After earth has stopped the ears. Now you will not swell the rout Of lads that wore their honours out, Runners whom renown outran And the name died before the man. So set, before its echoes fade, The fleet foot on the sill of shade, And hold to the low lintel up The still-defended challenge-cup. And round that early-laurelled head Will flock to gaze the strengthless dead, And find unwithered on its curls The garland briefer than a girl’s. ii iii Contents Preface........................................................................................................................... vi Abstract ......................................................................................................................... -

Capitalism and the New River Valley, 1745-1789. B

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Winter 1996 Economic Interdependence Along a Colonial Frontier: Capitalism and the New River Valley, 1745-1789. B. Scott rC awford Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the American Studies Commons, Economic History Commons, and the United States History Commons ECONOMIC INTERDEPENDENCE ALONG A COLONIAL FRONTIER: CAPITALISM AND THE NEW RIVER VALLEY, 1745-1789 by B. Scott Crawford B.S. May 1994, Radford University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY December 1996 Approved by: Jane T. Merritt (Director) J. Lawes (Member) James R Sw Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1383134 Copyright 1997 by Crawford, Benjamin Scott All rights reserved. UMI Microform 1383134 Copyright 1997, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT ECONOMIC INTERDEPENDENCE ALONG A COLONIAL FRONTIER: CAPITALISM AND THE NEW RIVER VALLEY, 1745-1789. B. Scott Crawford Old Dominion University, 1996 Director: Dr. Jane T. Merritt Historians have generally placed the beginning o f capitalism in the United States in the early- to mid-nineteenth century. This assumes that the industrialization of the New England states fostered in a modem economic environment for the country as a whole.