Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

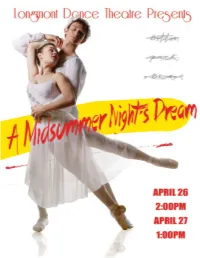

A Midsummer Night's Dream

EDUCATION RESOURCE Education rnzb.org.nz facebook.com/nzballet THE VODAFONE SEASON OF NATIONAL SPONSOR SUPPORTED BY MAJOR SUPPORTER SUPPORTING EDUCATION CONTENTS Curriculum 3 Ballet based on Shakespeare’s play 4 A Midsummer Night’s Dream ‘Shakespeare’s comic (world premiere) 5 The story of A Midsummer Night’s Dream 7 masterpiece of love, A brief synopsis for the classroom 7 Mendelssohn’s music for A Midsummer mistaken identities Night’s Dream 8 and magical mayhem A new score for a new ballet 9 A Midsummer Night’s Dream set and has been the source of costumes 11 Q & A with set and costume designer inspiration for artists of Tracy Grant Lord 13 Introducing lighting designer Kendall Smith 15 all genres for centuries. Origin of the fairies 16 My aim is to create A Midsummer Night’s Dream word puzzle 17 Identify the characters with their something fresh and emotions 18 Ballet timeline 20 vibrant, bubbling with all Let’s dance! 21 Identifying the two groups of characters the delight and humour through movement 23 that Shakespeare offers Answers 24 us through the wonderful array of characters he conjured up. As with any great story I want to take my audience on a journey so that every individual can have their own Midsummer Night’s Dream.” LIAM SCARLETT 2 CURRICULUM In this unit you and your students will: LEARNING OBJectives FOR • Learn about the elements that come Levels 7 & 8 together to create a theatrical ballet experience. Level 7 students will learn how to: • Identify the processes involved in making a • Understand dance in context – Investigate theatre production. -

Matt Doeden THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Matt Doeden

DOEDEN Matt Doeden THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Matt Doeden Lerner Publications Minneapolis Content consultant: Eric Juhnke, Professor of History, Briar Cliff University Copyright © 2018 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise— without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Lerner Publications Company A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Doeden, Matt, author. Title: World War II resistance fighters / by Matt Doeden. Description: Minneapolis : Lerner Publications, [2018] | Series: Heroes of World War II | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Grades 4–6. | Audience: Ages 8–12. Identifiers: LCCN 2017010790 (print) | LCCN 2017011941 (ebook) | ISBN 9781512498196 (eb pdf) | ISBN 9781512486414 (lb : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Anti-Nazi movement—History—20th century—Juvenile literature. | Anti-Nazi movement—Europe—Biography—Juvenile literature. | Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Juvenile literature. | Germany— History—1933–1945—Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC DD256.3 (ebook) | LCC DD256.3 .D58 2018 (print) | DDC 940.53/1—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010790 Manufactured in the United States of America 1-43465-33205-6/14/2017 CONTENTS Introduction Teenage Terror 4 Chapter 1 Acts of Sabotage 8 Chapter 2 Knowledge Is Power 14 Chapter 3 Rescue Operations 18 Chapter 4 Rising Up 22 Timeline 28 Source Note 30 Glossary 30 Further Information 31 Index 32 INTRODUCTION TEENAGE TERROR Eighteen-year-old Si mone Se gouin stayed low. -

AMND-Program-Final.Pdf

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR KRISTIN KINGSLEY Story & Selected Lyrics from WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Music by FELIX MENDELSSOHN Ballet Mistress STEPHANIE TULEY Music Director/Conductor BRANDON MATTHEWS Production Design SEAN COCHRAN Technical Director ISAIAH BOOTHBY Lighting Design DAVID DENMAN Costume Design NAOMI PRENDERGAST, SUSIE FAHRING, ANN MARCECA, & WANDA RICE WITH STRACCI FOR DANCE NIWOT HIGH SCHOOL AUDITORIUM APRIL 26 2:00PM APRIL 27 1:00PM Longmont Dance Theatre Our mission is simply stated but it is not simple to achieve: we strive to enliven and elevate the human spirit by means of dance, specifically the perfect form of dance known as ballet. A technique of movement that was born in the courts of kings and queens, ballet has survived to this day to become one of the most elegant, most adaptable and most powerful means of human communication. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR BALLET MISTRESS Kristin Kingsley Stephanie Tuley LDT BOARD OF DIRECTORS RESIDENT OPERATION PERSONNEL President Susan Burton Production & Design Vice President Dolores Kingsley Lighting Designer/ David Denman Secretary Marcella Cox Production Stage Manager Members Sean Cochran, Jeanine Hedstrom, Eileen Hickey, Stage Manager Jenn Zavattaro David Kingsley, & Moriah Sullivan Technical Dir./Master Carpenter Isaiah Boothby Ballet Guild Liason Cathy McGovern Scenic Design & Fabrication Sean Cochran with Enigma Concepts and Designs Properties Coordinator Lisa Taft House Manager Marcella Cox RESIDENT COMPANY MANAGEMENT Auditorium Manager Jason Watkins (Niwot HS Auditorium) Willow McGinty Office -

Johnny Hallyday 1 Johnny Hallyday

Johnny Hallyday 1 Johnny Hallyday Johnny Hallyday Johnny Hallyday au festival de Cannes 2009. Données clés Nom Jean-Philippe Smet Naissance 15 juin 1943 Paris Pays d'origine France Activité principale Chanteur Activités annexes Acteur Genre musical RockBluesBalladeRock 'n' rollVariété françaiseRhythm and bluesPopCountry Instruments Guitare Années d'activité Depuis 1960 Labels Vogue Philips-Phonogram-Mercury-Universal Warner [1] Site officiel www.johnnyhallyday.com Johnny Hallyday 2 Composition du groupe Entourage Læticia Hallyday David Hallyday Laura Smet Eddy Mitchell Sylvie Vartan Nathalie Baye Johnny Hallyday, né Jean-Philippe Smet le 15 juin 1943 à Paris, est un chanteur, compositeur et acteur français. Avec plus de cinquante ans de carrière, Johnny Hallyday est l'un des plus célèbres chanteurs francophones et l'une des personnalités les plus présentes dans le paysage médiatique français, où plus de 2100 couvertures de magazines lui ont été consacrées[2]. Si Johnny Hallyday n'est pas le premier à chanter du rock 'n' roll en France[3], il est le premier à populariser cette musique dans l'Hexagone[4],[5]. Après le rock, il lance le twist en 1961 et l'année suivante le mashed potato (en)[6] et s'il lui fut parfois reproché de céder aux modes musicales[7], il les a toutefois précédées plus souvent que suivies. Les différents courants musicaux auxquels il s'est adonné, rock 'n' roll, rhythm and blues, soul, rock psychédélique, pop puisent tous leurs origines dans le blues. Johnny est également l'interprète de nombreuses chansons de variété, de ballades, de country, mais le rock reste sa principale référence[6]. -

Country Christmas ...2 Rhythm

1 Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 10. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 10th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 10. Janu ar 2005 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. day 10th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken wir uns für die gute mers for their co-opera ti on in 2004. It has been a Zu sam men ar beit im ver gan ge nen Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY CHRISTMAS ..........2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................86 COUNTRY .........................8 SURF .............................92 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............25 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............93 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......25 PSYCHOBILLY ......................97 WESTERN..........................31 BRITISH R&R ........................98 WESTERN SWING....................32 SKIFFLE ...........................100 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................32 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............100 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................33 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........33 POP.............................102 COUNTRY CANADA..................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................108 COUNTRY -

Sommaire Catalogue National Octobre 2011

SOMMAIRE CATALOGUE NATIONAL OCTOBRE 2011 Page COMPACT DISCS Répertoire National ............................................................ 01 SUPPORTS VINYLES Répertoire National ............................................................. 89 DVD / HDDVD / BLU-RAY DVD Répertoire National .................................................... 96 L'astérisque * indique les Disques, DVD, CD audio, à paraître à partir de la parution de ce bon de commande, sous réserve des autorisations légales et contractuelles. Certains produits existant dans ce listing peuvent être supprimés en cours d'année, quel qu'en soit le motif. Ces articles apparaîtront de ce fait comme "supprimés" sur nos documents de livraison. NATIONAL 1 ABD AL MALIK Salvatore ADAMO (Suite) Château Rouge Master Serie(MASTER SERIE) 26/11/2010 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 20/08/2009 POLYDOR / POLYDOR (557)CD (899)CD #:GACFCH=ZX]\[V: #:GAAHFD=V^[U[^: Dante Zanzibar + La Part De L'Ange(2 FOR 1) 03/11/2008 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 19/07/2010 POLYDOR / POLYDOR (561)CD (928)2CD #:GAAHFD=VW]\XW: #:GAAHFD=W]ZWYY: Isabelle ADJANI Château Rouge Pull marine(L'ORIGINAL) 14/02/2011 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 08/04/1991 MERCURY / MERCURY (561)CD (949)CD #:GACFCH=[WUZ[Z: #:AECCIE=]Y]ZW\: ADMIRAL T Gibraltar Instinct Admiral 12/06/2006 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 19/04/2010 AZ / AZ (899)CD (557)CD #:GACEJI=X\^UW]: #:GAAHFD=W[ZZW^: Le face à face des coeurs Instinct Admiral(ECOPAK) 02/03/2004 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 20/09/2010 AZ / AZ (606)CD (543)CD #:GACEJI=VX\]^Z: #:GAAHFD=W^XXY]: ADAM & EVE Adam & Eve La Seconde Chance Toucher l'horizon -

TONYPAT... Co,Ltd

Fév 2018 N°12 Journal mensuel gratuit www.pattaya-journal.com TONYPAT... Co,ltd Depuis 2007 NOUVEAU ! Motorbike à louer YAMAHA avec assurance AÉROX 155CC NMAX - PCX & TOUT MODÈLE Des tarifs pour tous Livraison gratuite à partir les budgets d’une semaine de location Ouverture de 10h à 19h30, 7 jours sur 7 Tony Leroy Tonypat... Réservation par internet 085 288 6719 FR - 038 410 598 Thaï www.motorbike-for-rent.com [email protected] | Soi Bongkoch 3 Potage et Salade Bar Compris avec tous les plats - Tous les jours : Moules Frites 269฿ • Air climatisé - Internet • TV Led 32” Cablée ifféren d te • Réfrigérateur 0 s • Coffre-fort 2 b i s èr e es belg Chang RESTAURANT - BAR - GUESTHOUSE Pression Cuisine Thaïe Cuisine Internationale 352/555-557 Moo 12 Phratamnak Rd. Soi 4 Pattaya Tel : 038 250508 email: [email protected] www.lotusbar-pattaya.com Pizzas EDITO LA FÊTE DES AMOUREUX Le petit ange Cupidon armé d’un arc, un carquois et une fleur est de retour ce mois-ci. Il va décocher ses flèches d’argent en pagaille et faire encore des victimes de l’amour. Oui car selon la mythologie, quiconque est touché par les flèches de Cupidon tombe amoureux de la personne qu’il voit à ce moment-là. Moi par exemple... Je m’baladais sur l’avenue, le cœur ouvert à l’inconnu, j’avais envie de dire bonjour à n’importe qui, n’importe qui et ce fut toi, je t’ai dit n’importe quoi, il suffisait de te parler, pour t’apprivoiser.. -

American Airmen Shot Down Over Europe Had a Sophisticated Web Of

USAF photo emember: Do Nothing. Say Nothing. Write Nothing Which “ Could Betray Our Friends.” This notice, posted for American airmen shot down over aircrew during World War II, Rreminded them of a reassuring secret: Europe had a sophisticated web of If they were shot down over France, Resistance networks were ready and eager supporters for attempts to avoid the to hide them from the Germans. Nazis and reach freedom. There was good reason to be optimistic. The Resistance enabled more than 3,000 Allied airmen to disguise their identities and walk out of German-occupied Western Europe. Airmen shot down in France and Belgium had especially good chances of making it out. Future American ace and test pilot legend Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager was shot down by Focke-Wulf 190s on a mission over France on March 5, 1944. “Before I had gone 200 feet, half a dozen Frenchmen ran up to me,” Yeager later reported. They brought him a change of clothes and hid him in a barn. Under the care of the Resistance, Yeager was transported to southern France, hiked into Spain on March 28, reached the British fortress at Gibraltar on May 15, and was in England by May 21, 1944. Yeager’s speedy trip was made possible by years of effort to build networks for moving airmen from the moment they landed in their parachutes to the moment they reached friendly or neutral territory. The evading airman’s journey always began with immediate concealment. Then they sheltered with families, often in several locations. Next they traveled in cars and trucks, bicycled, and even rode A B-24 crash-lands near Eindhoven, Holland. -

Ce Document Est Extrait De La Base De Données Textuelles Frantext Réalisée Par L'institut National De La Langue Française (Inalf)

Ce document est extrait de la base de données textuelles Frantext réalisée par l'Institut National de la Langue Française (InaLF) [La] tentation de Saint-Antoine [Document électronique] : [version de 1849] / Gustave Flaubert I p205 Messieurs les démons, laissez-moi donc ! Messieurs les démons, laissez-moi donc ! mai 1848. -septembre 1849. G Flaubert. Sur une montagne. à l' horizon, le désert ; à droite, la cabane de saint Antoine, avec un banc devant sa porte ; à gauche, une petite chapelle de forme ovale. Une lampe est accrochée au-dessus d' une image de la sainte vierge ; par terre, devant la cabane, corbeilles en feuilles de palmiers. Dans une crevasse de la roche, le cochon de l' ermite dort à l' ombre. Antoine est seul, assis sur le banc, occupé à faire ses paniers ; il lève la tête et regarde vaguement le soleil qui se couche. Antoine. Assez travaillé comme cela. Prions ! Il se dirige vers la chapelle. Tout à l' heure ces lianes tranchantes m' ont coupé les mains... p206 quand' ombre de la croix aura atteint cette pierre, j' allumerai la lampe et je commencerai mes oraisons. Il se promène de long en large, doucement, les bras pendants. Le cel est rouge, le gypaète tournoie, les palmiers Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. frissonnent ; sur la crotte de porc voilà les scarabées qui se traînent ; l' ibis a fermé son bec pointu et la cigogne blanche, au sommet des obélisques, commence à s' endormir la tête passée sous son aile ; la lune va se lever. -

1815, WW1 and WW2

Episode 2 : 1815, WW1 and WW2 ‘The Cockpit of Europe’ is how Belgium has understatement is an inalienable national often been described - the stage upon which characteristic, and fame is by no means a other competing nations have come to fight reliable measure of bravery. out their differences. A crossroads and Here we look at more than 50 such heroes trading hub falling between power blocks, from Brussels and Wallonia, where the Battle Belgium has been the scene of countless of Waterloo took place, and the scene of colossal clashes - Ramillies, Oudenarde, some of the most bitter fighting in the two Jemappes, Waterloo, Ypres, to name but a World Wars - and of some of Belgium’s most few. Ruled successively by the Romans, heroic acts of resistance. Franks, French, Holy Roman Empire, Burgundians, Spanish, Austrians and Dutch, Waterloo, 1815 the idea of an independent Belgium nation only floated into view in the 18th century. The concept of an independent Belgian nation, in the shape that we know it today, It is easy to forget that Belgian people have had little meaning until the 18th century. been living in these lands all the while. The However, the high-handed rule of the Austrian name goes back at least 2,000 years, when Empire provoked a rebellion called the the Belgae people inspired the name of the Brabant Revolution in 1789–90, in which Roman province Gallia Belgica. Julius Caesar independence was proclaimed. It was brutally was in no doubt about their bravery: ‘Of all crushed, and quickly overtaken by events in these people [the Gauls],’ he wrote, ‘the the wake of the French Revolution of 1789. -

Escape and Evasion Society 1990 1991 Winter Communications I

TI{E AIR FORCES ESCAPE AND EVASION SOCIETY 1990 1991 WINTER COMMUNICATIONS I A.F.E.E.S. REUNION ! MAY 1ST, 2ND, 3RD, 4TH, & 5TH, 1gg0 ]HIYATT ]R]EG]ENCY IHIOT]E]L (Formerly Irvine Hilton Hotel and Towers) ]I]R\T]tNtr,, CA]LN]FO]RN]I^A, IU.S"A. Page 2 THE PRIESIIDENT'S N/flESSAGE Onct again members of AFEES have enjoyed the warm hospitality of our WWII AFEES history. helpers. Elsewhere in this issue you Irvine, California in May' RALPH PATTON of Communications you will See all in read about our activities on ffi this outstanding visit to NilE,R.E'S WNil^A,]I YOTJ CAN DO I Holland, France, Belgium and Andorra. But I waut to point out some of the true friends of AFEES who made our visit so memorable. We owe a vote of thanks to Leslie Atkinson' Dr & Mrs Gabriel Nahas, Nel Lin4 Joke Folmer, Peter vatr den Hurk, Nadine Antoine Dumon aud Raymond Etterbeek plus many others who made sign- IT'S YOI]R RESPONSIBILITY! HELP TO DOCUMENT AND PERPETUATE THIS GREAT HISTORY OF THE ESCAPE AND EUASION SOCIETY its famous submarine pens and other points of interest in Brittany' A]R FORCES -Stilt SincerelY, Herb and Milficent are hard at work planning our 1991 an' R*t"r.fu "CArPn K. PATToN' em*ryent F'R.ONf CN.AYTON DAVND January is fast ou that the or dues for'1991 sh e before the additi:oiflaooluonar uit.iafter JuouuwJanuary l, 1991' It is very expensive toiay lhe .*f"or., that aiways occur at r-eunibn time' Therefore ?"v.".di: itil""i-o"""ti"ns oi tunos are alwaye welcome, p-articularly at this t.uoioo in kvine where we expect over 400 members and a lot of them*W. -

Battle of Le Boulou Paulilles to Banyuls-Sur-Mer

P-OP-O Life LifeLife inin thethe Pyrénées-Orientales Pyrénées Orientales Out for the Day Battle of Le Boulou Walk The Region Paulilles to Banyuls-sur-Mer AMÉLIOREZ VOTRE ANGLAIS Autumn 2012 AND TEST YOUR FRENCH FREE / GRATUIT Nº 37 Your English Speaking Services Directory www.anglophone-direct.com Fond perdu 31/10/11 9:11 Page 1 Edito... Don’t batten down those hatches yet ‚ summer Register for our is most definitely not over here in the P-O and free weekly newsletter, we have many more long sunny days ahead. Lazy and stay up to date with WINDOWS, DOORS, SHUTTERS & CONSERVATORIES walks on deserted golden beaches, meanderings life in the Pyrénées-Orientales. www.anglophone -direct.com through endless hills, orchards and vines against a background of cloudless blue sky, that incredible Installing the very best since 1980 melange of every shade of green, red, brown and gold to delight Call or visit our showroom to talk the heart of artist and photographer, lift the spirits and warm the soul. with our English speaking experts. We also design Yes, autumn is absolutely my favourite time of the year with its dry warm days and and install beautiful cooler nights and a few drops of rain after such a dry summer will be very welcome! Unrivalled 30 year guarantee conservatories. We have dedicated a large part of this autumn P-O Life to remembrance, lest we ever forget the struggles and lost lives of the past which allow No obligation free quotation – Finance available subject to status us to sit on shady terraces in the present, tasting and toasting the toils of a land which has seen its fair share of blood, sweat and tears.