Annex 2 USAID South Sudan Gender Based Violence Prevention And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Informal Peace Efforts

CMI BRIEF 2018:7 1 NUMBER 7 CMI BRIEF NOVEMBER 2018 Photo courtesy of Isis-WICCE Women’s informal peace efforts: Grassroots activism in South Sudan AUTHORS South Sudanese women have been grossly under-represented Helen Kezie-Nwoha in formal peace negotiations. However, they have been active Juliet Were in informal peacebuilding at the local level where peace means rebuilding society. Such informal peacebuilding is radically different to formal peace negotiations where male warlords and political leaders in new positions of power divide the spoils of war. This brief describes women’s informal peace work in South Sudan, and shows the extensive and valuable, but often unrecognized work that women’s organizations do. We also look at how women’s roles in formal processes are informed by women’s informal work. 2 CMI BRIEF 2018:7 Methodology In this study, we conducted individual and focus groups discussions with women activists from groups located in South Sudan and in Uganda. We completed 21 individual interviews, eight focus group discussions (with a total of 111 women) and two community meetings with 90 women in all. The interviews were conducted between June 2017 and July 2018. Fighting between different warring factions caused delays and made it difficult to access study locations. The long road to peace Women’s role in formal peace processes South Sudan gained independence from Sudan on 9 July 2011. Since then, South Sudan has been marred by internal conflicts. What started as a power struggle Women’s under-representation in peace between President Salva Kiir and his deputy, former negotiations is the norm rather than Vice President Riek Machar, quickly devolved into a war the exception. -

Sudan: the Crisis in Darfur and Status of the North-South Peace Agreement

Sudan: The Crisis in Darfur and Status of the North-South Peace Agreement Ted Dagne Specialist in African Affairs June 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33574 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Sudan: The Crisis in Darfur and Status of the North-South Peace Agreement Summary Sudan, geographically the largest country in Africa, has been ravaged by civil war intermittently for four decades. More than 2 million people have died in Southern Sudan over the past two decades due to war-related causes and famine, and millions have been displaced from their homes. In July 2002, the Sudan government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) signed a peace framework agreement in Kenya. On May 26, 2004, the government of Sudan and the SPLM signed three protocols on Power Sharing, on the Nuba Mountains and Southern Blue Nile, and on the long disputed Abyei area. The signing of these protocols resolved all outstanding issues between the parties. On June 5, 2004, the parties signed “the Nairobi Declaration on the Final Phase of Peace in the Sudan.” On January 9, 2005, the government of Sudan and the SPLM signed the final peace agreement at a ceremony held in Nairobi, Kenya. In April 2010, Sudan held national and regional elections. In January 2011, South Sudan held a referendum to decide on unity or independence. Abyei was also expected to hold a referendum in January 2011 to decide whether to retain the current special administrative status or to be part of South Sudan. -

Building Legitimate and Accountable Government in South Sudan Re

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.5, No.8, 2015 Building Legitimate and Accountable government in South Sudan Re-thinking inclusive governance in the post CPA-2005 Dalmas O. Omia Research fellow, Institute of Anthropology, Gender and African Studies, University of Nairobi, Kenya Email: [email protected] Josephine Anyango Obonyo Ph.D Lecturer Institute of Women Gender and Development Studies, Egerton University, Kenya Email: [email protected] Abstract Inclusive governance is significant to the realisation of democracy and peace dividends in states emerging from conflict. In principle, it offers platform for equitable representation of the ethnic majority, minority, marginalised and indigenous groups in public decision making bodies as well as ensuring that these groups benefit equally from development initiatives. In South Sudan, the exercise of inclusivity has been marred with contradictions between constitutional provisions and extant practices, for example, political parties are found to be the foci for rewarding the ‘warlords’ dubbed as freedom fighters at the expense of participatory civilian structures, the nerves of ethnic factionalism over nationalism, exercise of centralised nomination system, all of which breed disaffection and tensions among the citizenry. Moreover, the observed militarisation of public service, perception of ethnic favouritism in public employment and appointments, the ‘felt’ development marginalisation of regions outside Central Equitoria, and unequal share of national resources comprise practices that violate the foundations of inclusive governance. In effect, these malpractices around inclusivity have fermented call for federalism (return to 23 semi-autonomous colonial districts with federal mandates) as a viable inclusive development platform over the current constitutionally mandated decentralisation (where South Sudan is sub- divided into 10 states). -

Evaluation of Usaid/South Sudan's Democracy And

EVALUATION OF USAID/SOUTH SUDAN’S DEMOCRACY AND GOVERNANCE ACTIVITIES UNDER THE IRI PROJECT — 2012-2014 APRIL 2016 This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by Luis Arturo Sobalvarro and Dr. Raymond Gervais under contract with Management Systems International (MSI). EVALUATION OF USAID/SOUTH SUDAN’S DEMOCRACY AND GOVERNANCE ACTIVITIES UNDER THE IRI PROJECT 2012 – 2014 Management Systems International Corporate Offices 200 12th Street, South Arlington, VA 22202 USA Tel: + 1 703 979 7100 Contracted under Order No. AID-668-I-13-00001 Monitoring and Evaluation Support Project DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. ii CONTENTS ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... II EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 7 Purpose of Evaluation .............................................................................................................................................. -

Oregon Obituaries II

Oregon Obituaries II GFO Members may view this collection in MemberSpace > Digital Collections > Indexed Images > Oregon Obituaries II. Non-members may order a copy at GFO.org > Resources > Indexes > All Indexes > Oregon Obituaries II Newspaper Newspaper Surname Given Name Article Type Comments Scan # Article Date Title City Aaben Alide Funeral notice Aaben Alide 1992 1992 (NG) (NG) Aamodt Edwin D Obituary Clarke M4 (7) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Aasby Jerry G Obituary Clarke M4 (19) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Abacherli Zeno Anton Obituary Clarke M4 (6) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Abell Rowena Marie Obituary Clarke M4 (12) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Absten Leila Heinz Obituary Clarke M4 (17) 1990 Statesman Journal Salem Absten Margaret Middleton Obituary Clarke M4 (9) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Acevedo Pedro Vasquez Obituary Acevedo Pedro 1999 1999 (NG) (NG) Ackerson Jean L Obituary Clarke M4 (14) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Adair Laverne Obituary Clarke M4 (18) 1996 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Anna G Obituary Clarke M4 (4) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Beatrice M Obituary Adams Beatrice 1992 1992 (NG) (NG) Adams Daisy Irene Obituary Clarke M4 (7) 1996 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Edward Obituary Clarke M4 (1) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Ella Lee Obituary Clarke M4 (4) 1995 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Gladys Obituary Clarke M4 (11) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Joseph Z Obituary Adams Joseph 1993 1993 (NG) (NG) Adams Joyce Elaine Obituary Clarke M4 (10) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Juanita V Obituary -

Dear Graduates, Nova Southeastern University Takes

Dear Graduates, Nova Southeastern University takes enormous pride in your success. On behalf of NSU’s faculty, staff, and Board of Trustees, I salute your academic and personal achievement. You have reached this milestone through hard work and intellectual effort, and we are pleased to recognize your dedication with today’s commencement ceremony. Reflect on the gifts of knowledge and support you have received. Celebrate the friendships, skills, and strengths you have forged. Embrace the opportunity to apply these treasures as you start a new chapter in your life, hopefully, following your passion, not your fortune. Our best wishes are with you today and in the future. Congratulations! George L. Hanbury II, Ph.D. NSU President and CEO CEREMONY SCHEDULE May 16, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. Shepard Broad College of Law May 17, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. All Undergraduate Degrees May 17, 2021, at 3:00 p.m. H. Wayne Huizenga College of Business and Entrepreneurship May 18, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. College of Dental Medicine Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine College of Psychology May 18, 2021, at 3:00 p.m. College of Optometry College of Pharmacy Ron and Kathy Assaf College of Nursing May 19, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. Abraham S. Fischler College of Education and School of Criminal Justice Halmos College of Arts and Sciences College of Computing and Engineering May 19, 2021, at 3:00 p.m. Dr. Pallavi Patel College of Health Care Sciences 2 CLASS OF 2021 THE ACADEMIC PROCESSION Grand Marshal Degree Candidates Members of the Faculty Members of the Board of Trustees Distinguished Guests University Officials 3 WELCOME TO THE 2021 COMMENCEMENT CEREMONIES for NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY May 16 to 19, 2021 4 CLASS OF 2021 ORDER OF EXERCISES SHEPARD BROAD COLLEGE OF LAW MAY 16, 2021, AT 9:30 A.M. -

A Strategy for Achieving Gender Equality in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT January 28, 2014 A Strategy for Achieving Gender Equality in South Sudan Jane Kani Edward ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study is a product of the Sudd Institute Gender Fellowship in South Sudan awarded to me to conduct research from June to August 2013. The fellowship was made possible by a generous grant from the United States Institute for Peace (USIP). I am grateful to the Sudd Institute and USIP for making this endeavor possible. Numerous individuals and institutions have made the fellowship and fieldwork particularly successful. I am extremely thankful to government officials, primary school administrators, and members of the faculty of Juba University, who welcomed me to their offices and homes, accepted to be interviewed, and provided important documents used in the analysis of the collected data. Special thanks also to members of Lo’bonog Women Group, Rabita Salam Wa Muhaba, and the Ayiki Farmers Association, who shared their experiences of organizing and the challenges they face. Their participation was critically important in making this study successful. Finally, I would like to thank all the staff of the Sudd Institute in Juba, South Sudan for making my research experience during my visit a success. © The Sudd Institute || SPECIAL REPORT | 2 ABBREVIATIONS AEOs Agricultural Extension Officers CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement ECOSOC Economic and Social Council GAD Gender and Development GBV Gender-Based Violence GOSS Government of Southern -

CUNY Baccalaureate for Unique and Interdisciplinary Studies

Greetings from the President May 30, 2018 Dear Graduates: Congratulations! You have reached a most significant milestone in your life. Your hard work, determination, and commitment to your education have been rewarded, and you and your loved ones should take pride in your accomplishments and successes. Hunter College certainly takes pride in you. ' Your Hunter education has prepared you to meet the challenges of a world that is rapidly changing politically, socially, economically, ~ . technologically. As part of the next generation of thoughtful, responsible, and intelligent leacfets;·: you will make a real difference wherever you apply your knowledge and skills. Endless 'Opportunities await you. As you pursue your goals and move forward with your professional and personal lives., please carry with you Hunter's commitment to community, diversity, and service to others. We look forward to hearing great things about you, and we hope you will stay connected to the exciting activities and developments on campus. Please remember Hunter College and know that you will always be part of our family. Best wishes for continued success. Sincerely, ~vi Jennifer J. Raab President Order ofExercises Presiding Jennifer J. Raab, President Eija Ayravainen, Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean ofStudents Opening Ceremony Michael F. Mazzeo, Macaulay Honors College, Bachelor ofArts '18 Processional President's Party and Members of the Faculty Graduates and Candidates for Graduation National Anthem Joanna Malaszczyk, Master ofArts '18 Bagpiper Ian A. Sherman, Doctor ofNursing Practice '18 Greetings William C. Thompson, Jr., Chair, Board ofTrustees of The City University ofNew York Matthew Sapienza, Senior Vice Chancellor and ChiefFinancial Officer of The City University ofNew York ' Charge to the Graduates and Candidates for Graduation President Jennifer J. -

Spring-2018-Deans-List.Pdf

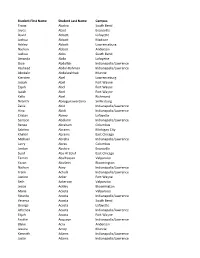

Student First Name Student Last Name Campus Tiwaa Ababio South Bend Joyce Abad Evansville David Abbott Lafayette Joshua Abbott Madison Ashley Abbott Lawrenceburg Nathan Abbott Anderson Joshua Abbs South Bend Amanda Abdo Lafayette Skye Abdullah Indianapolis/Lawrence Rasheed Abdul-Rahman Indianapolis/Lawrence Abobakr Abdulwahhab Muncie Kiersten Abel Lawrenceburg Josiah Abel Fort Wayne Elijah Abel Fort Wayne Isaiah Abel Fort Wayne Kelly Abel Richmond Nilanthi Abeygunawardana Sellersburg Zakia Abid Indianapolis/Lawrence Hina Abidi Indianapolis/Lawrence Cristan Abney Lafayette Samson Abolarin Indianapolis/Lawrence Renee Abraham Columbus Sabrina Abrams Michigan City Khalial Abrams East Chicago Michael Abreha Indianapolis/Lawrence Larry Abreu Columbus Jordan Abshire Evansville Suad Abu Al Zoluf East Chicago Tamim Abulhassan Valparaiso Yazan AbuSeini Bloomington Nathan Acey Indianapolis/Lawrence Frank Achulli Indianapolis/Lawrence Justine Acker Fort Wayne Seth Ackerson Valparaiso Jessie Ackley Bloomington Maria Acosta Valparaiso Ricardo Acosta Indianapolis/Lawrence Yesenia Acosta South Bend George Acosta Lafayette Athenea Acosta Indianapolis/Lawrence Elijah Acosta Fort Wayne Faythe Acquaye Indianapolis/Lawrence Blake Acra Anderson Jessica Acrey Muncie Kenneth Adams Indianapolis/Lawrence Justin Adams Indianapolis/Lawrence Pamela Adams Indianapolis/Lawrence Felicya Adams Indianapolis/Lawrence Hannah Adams Evansville Ariel Adams Bloomington Gunnar Adams Fort Wayne Stevie Adams Terre Haute Cameron Adams Indianapolis/Lawrence Alex Adams South Bend -

Nebraska Education Directory 2008-2009

NEBRASKA EDUCATION DIRECTORY 2008-2009 Roger D. Breed Commissioner of Education Scott Swisher Deputy Commissioner Nebraska Department of Education 301 Centennial Mall South P.O. Box 94987 Lincoln, Nebraska 68509-4987 Phone: (402) 471- 2295 FAX: (402) 471- 0117 WEB SITE: http://www.nde.state.ne.us Ann Ahrens of Minden High School in Minden, NE designed the feature artwork for the 2008-2009 Nebraska Education Directory. Ann is the daughter of Rhonda and Kirk Ahrens. Ann’s artwork is entitled “Step & Spin.” Chris Dolan was Ann’s art teacher. Printed copies are not available for the 2008-2009 Education Directory. The Department of Education will use electronic means whenever possible to publish information to our customers. The Directory is accessible on the Internet through our web site in various formats to view, print, or download. http://ess.nde.state.ne.us This information is current as of January 2009. Any changes after that time will not be reflected here. Go to “DIRECTORY SEARCH” listed under the “A-Z Topic List” at http://www.nde.state.ne.us for the most up-to-date information. 2008-2009 Nebraska Education Directory TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SEARCH THE DIRECTORY ................................................................................. 3 NDE Organizational Structure ............................................................................... 4 Department of Education Staff and Services Directory ......................................... 5 Job Position and Assignment Abbreviations ........................................................ -

Country Gender Profile Republic of South Sudan Final Report

Country Gender Profile Republic of South Sudan Final Report March 2017 Japan International Cooperation Agency(JICA) IC Net Limited EI JR 17-047 Summary Socio-Economic Situation and Gender in South Sudan General Situation of South Sudan/Conflicts in South Sudan The area comprising South Sudan is about 1.7 times the size of Japan with an estimated population of 11.7 million. The majority of which are engaged in nomadic grazing and agriculture. The country has more than 60 ethnic groups and the tensions among them have been a serious issue. The economy depends on its oil reserves. South Sudan achieved its independence in 2011 after two civil wars. However, it is still politically unstable, and this instability has culminated in the political clashes in December 2013 and July 2016. Armed conflicts continue and severely affect the lives of its population. Conflict and Women Conflicts severely affect South Sudanese women socially, economically, physically and psychologically. Sexual violence has been used as a weapon of war during and even after the civil wars, and women continue to suffer. South Sudanese women were also mobilized as soldiers or as supporters during the civil wars. Their involvement in the civil wars has paved the way for their political engagement and the establishment of the Ministry of Gender. Women struggled to play an active role in peace negotiations. They have been successful to some extent and have been able to send some of their own as members of a negotiation team. However, there is a long way to go in order to have women at the official negotiation table. -

Integrating Gender Into the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States

www.cordaid.org POLICY PAPER SEPTEMBER 2012 INTEGRATING GENDER INTO THE NEW DEAL FOR ENGAGEMENT IN FRAGILE STATES The New Deal offers an important opportunity to key recommendations advance women, peace and security issues. This policy paper has identified entry points for integrating a gender ■■ Prioritise women’s voices and strengthen engagement perspective into the various aspects of the New Deal as with civil society around implementation of the well as its implementation in the pilot countries. The case New Deal studies from Afghanistan and South Sudan demonstrate ■■ Link the implementation of the New Deal to existing that much work has already been done by women’s in-country activities around the implementation of organisations to identify, prioritise and advocate around UNSCR 1325, and vice versa key issues of concern, and there is great interest among ■■ Apply a gender perspective to all analytical frameworks civil society to play a more active role in supporting the and approaches used to implement the New Deal implementation of the New Deal. The paper highlights key ■■ Integrate gender issues into fragility assessments recommendations and possible actions that could be taken ■■ Allocate adequate financing to women’s needs and to integrate a gender perspective as the New Deal piloting gender-related priorities continues in the coming months. ■■ Ensure that any indicators developed to monitor the PSGs reflect a gender perspective and are sex- disaggregated ■■ Increase communication and collaboration across government ministries to ensure a more coordinated approach to addressing gender issues in FCAS “Gender equality, and women’s NO PEACE participation, is critical to the WITHOUT WOMEN’S realisation of the central aims LEADERSHIP of the New Deal.” CARE.