Man and God at Palmyra: Sacrifice, Lectisternia and Banquets*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria Drought Response Plan

SYRIA DROUGHT RESPONSE PLAN A Syrian farmer shows a photo of his tomato-producing field before the drought (June 2009) (Photo Paolo Scaliaroma, WFP / Surendra Beniwal, FAO) UNITED NATIONS SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC - Reference Map Elbistan Silvan Siirt Diyarbakir Batman Adiyaman Sivarek Kahramanmaras Kozan Kadirli TURKEY Viransehir Mardin Sanliurfa Kiziltepe Nusaybin Dayrik Zakhu Osmaniye Ceyhan Gaziantep Adana Al Qamishli Nizip Tarsus Dortyol Midan Ikbis Yahacik Kilis Tall Tamir AL HASAKAH Iskenderun A'zaz Manbij Saluq Afrin Mare Al Hasakah Tall 'Afar Reyhanli Aleppo Al Bab Sinjar Antioch Dayr Hafir Buhayrat AR RAQQA As Safirah al Asad Idlib Ar Raqqah Ash Shaddadah ALEPPO Hamrat Ariha r bu AAbubu a add D Duhuruhur Madinat a LATAKIA IDLIB Ath Thawrah h Resafa K l Ma'arat a Haffe r Ann Nu'man h Latakia a Jableh Dayr az Zawr N El Aatabe Baniyas Hama HAMA Busayrah a e S As Saiamiyah TARTU S Masyaf n DAYR AZ ZAWR a e n Ta rtus Safita a Dablan r r e Tall Kalakh t Homs i Al Hamidiyah d Tadmur E e uphrates Anah M (Palmyra) Tripoli Al Qusayr Abu Kamal Sadad Al Qa’im HOMS LEBANON Al Qaryatayn Hadithah BEYRUT An Nabk Duma Dumayr DAMASCUS Tyre DAMASCUS QQuneitrauneitra Ar Rutbah QUNEITRA Haifa Tiberias AS SUWAIDA IRAQ DAR’A Trebil ISRAELI S R A E L DDarar'a As Suwayda Irbid Jenin Mahattat al Jufur Jarash Nabulus Al Mafraq West JORDAN Bank AMMAN JERUSALEM Bayt Lahm Madaba SAUDI ARABIA Legend Elevation (meters) National capital 5,000 and above First administrative level capital 4,000 - 5,000 Populated place 3,000 - 4,000 International boundary 2,500 - 3,000 First administrative level boundary 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 050100150 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 km 600 - 800 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material 400 - 600 on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal 200 - 400 status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Exhibition Checklist I. Creating Palmyra's Legacy

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST 1. Caravan en route to Palmyra, anonymous artist after Louis-François Cassas, ca. 1799. Proof-plate etching. 15.5 x 27.3 in. (29.2 x 39.5 cm). The Getty Research Institute, 840011 I. CREATING PALMYRA'S LEGACY Louis-François Cassas Artist and Architect 2. Colonnade Street with Temple of Bel in background, Georges Malbeste and Robert Daudet after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 16.9 x 36.6 in. (43 x 93 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 58. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 1 3. Architectural ornament from Palmyra tomb, Jean-Baptiste Réville and M. A. Benoist after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 18.3 x 11.8 in. (28.5 x 45 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 137. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 4. Louis-François Cassas sketching outside of Homs before his journey to Palmyra (detail), Simon-Charles Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 20. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 5. Louis-François Cassas presenting gifts to Bedouin sheikhs, Simon Charles-Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41 cm). -

ANCIENT NECROPOLIS UNEARTHED Italian Archaeologists Lead Dig Near Palmyra

Home > News in English > News » le news di oggi » le news di ieri » 2008-12-17 12:11 ANCIENT NECROPOLIS UNEARTHED Italian archaeologists lead dig near Palmyra (ANSA) - Udine, December 17 - An Italian-led team of experts has uncovered a vast, ancient necropolis near the Syrian oasis of Palmyra. The team, headed by Daniele Morandi Bonacossi of Udine University, believes the burial site dates from the second half of the third millennium BC. The necropolis comprises around least 30 large burial mounds near Palmyra, some 200km northeast of Damascus. ''This is the first evidence that an area of semi-desert outside the oasis was occupied during the early Bronze Age,'' said Morandi Bonacossi. ''Future excavations of the burial mounds will undoubtedly reveal information of crucial importance''. The team of archaeologists, topographers, physical anthropologists and geophysicists also discovered a stretch of an old Roman road. This once linked Palmyra with western Syria and was marked with at least 11 milestones along the way. The stones all bear Latin inscriptions with the name of the Emperor Aurelius, who quashed a rebellion led by the Palmyran queen Zenobia in AD 272. The archaeologists also unearthed a Roman staging post, or ''mansio''. The ancient building had been perfectly preserved over the course of the centuries by a heavy layer of desert sand. The team from Udine University made their discoveries during their tenth annual excavation in central Syria, which wrapped up at the end of November. The necropolis is the latest in a string of dazzling finds by the team. Efforts have chiefly focused on the ancient Syrian capital of Qatna, northeast of modern-day Homs. -

The Battle for Al Qusayr, Syria

June 2013 The Battle for al Qusayr, Syria TRADOC G-2 Intelligence Support Activity (TRISA) Complex Operational Environment and Threat Integration Directorate (CTID) [Type the author name] United States Army 6/1/2012 Threats Integration Team Threat Report Purpose To inform the Army training community of real world example of Hybrid Threat capabilities in a dynamic operating environment To illustrate current tactics for Hybrid Threat insurgent operations To illustrate Hybrid Threat counterinsurgency operations using a current conflict To provide a short history of the conflict in the al Qusayr and the al Assi basin To describe the importance of the lines of communications from Lebanon to Syria Executive Summary The al Qusayr area of operations is a critical logistics hub for the rebel forces fighting against the Syrian government known as the Free Syrian Army (FSA). A number of external actors and international terror organizations have joined the fight in the al Assi basin on both sides of the conflict. The al Assi basin and the city of al Qusayr can be considered critical terrain and key to the future outcome of the conflict in Syria. Conventional and unconventional as well as irregular forces are all present in this area and are adapting tactics in order to achieve a decisive outcome for their cause. Cover photo: Pro Regime Leaflets Dropped on al Qusayr During the Second Offensive, 21 MAY 2013. 2 UNCLASSIFIED Threats Integration Team Threat Report Map Figure 1. The al Assi River Basin and city of al Qusayr Introduction Al Qusayr, a village in Syria’s Homs district, is a traditional transit point for personnel and goods traveling across the Lebanon/Syria border. -

Terrestrial Forest Management Plan for Palmyra Atoll

Prepared for The Nature Conservancy Palmyra Program Terrestrial Forest Management Plan for Palmyra Atoll Open-File Report 2011–1007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Images showing native species of the terrestrial forest at Palmyra Atoll (on the left from top to bottom: red-footed boobies, an undescribed gecko, and a coconut crab). The forests shown are examples of Pisonia grandis forest on Lost Islet (above) and an example of coconut palm monoculture on Kaula Islet (below) at Palmyra Atoll. (Photographs by Stacie Hathaway, U.S. Geological Survey, 2008.) Terrestrial Forest Management Plan for Palmyra Atoll By Stacie A. Hathaway, Kathryn McEachern, and Robert N. Fisher Prepared for The Nature Conservancy Palmyra Program Open-File Report 2011–1007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Hathaway, S.A., McEachern, K., and Fisher, R.N., 2011, Terrestrial forest management plan for Palmyra Atoll: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011–1007, 78 p. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 25 Putin’s Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket by John W. Parker Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, August, 2012 (Russian Ministry of Defense) Putin's Syrian Gambit Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket By John W. Parker Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 25 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. July 2017 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. -

INA Plc. Exploration and Production Activities in Syria, Successful Achievement of Hydrocarbon Discoveries and Developments

INA Plc. exploration and production activities in Syria, successful achievement of hydrocarbon discoveries and developments T. Malviæ, M. \urekoviæ, . Šikonja, Z. Èogelja, T. Ilijaš, I. Kruljac REVIEW INA-Industry of Oil Plc. (Croatia) has been present in Syria since 1998, working on exploration and development of hydrocarbon fields located in the Hayan Block. Recently, INA Plc. has been preparing the exploration activities in the Aphamia Block as well. All exploration activities are led by INA Branch Office, while development and production (for now exclusively in Hayan Block) is operated by Hayan Petroleum Company, a joint venture between INA and SPC (Syrian Petroleum Company). Since 1998 six commercial discoveries were reported in the Hayan Block, namely Jihar, Al Mahr, Jazal, Palmyra, Mustadira and Mazrur Fields. The largest proven reserves are related to Jihar Field where hydrocarbons were discovered in heterogeneous reservoir sequences, mostly in the fractured Middle Triassic carbonate reservoirs of the Kurrachine Dolomites Formation. Complex reservoir lithology assumed advanced reservoir characterization that included integration of all geologic and engineering data. Such characterization included several or the following models and calculations: (1) estimation OHIP potential scenarios and production foreseeing by dynamical simulations; (2) structural interpretation from 3D seismic data; (3) petrophysical variables estimation based on core analysis, log data and well tests. Moreover, in some reservoirs facies distribution was made using stochastic simulations. Advanced computer modelling of rock fracture geometry had been applied using interpretation of image logs, combined with core data. Two discrete fracture network models were stochastically created, giving fracture’s parameters as input for dynamic simulations, also making to predict more production scenarios as base for the next development stage. -

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq As a Violation Of

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq as a Violation of Human Rights Submission for the United Nations Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights About us RASHID International e.V. is a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts and professionals dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Iraq. We are committed to de eloping the histor! and archaeology of ancient "esopotamian cultures, for we belie e that knowledge of the past is ke! to understanding the present and to building a prosperous future. "uch of Iraq#s heritage is in danger of being lost fore er. "ilitant groups are ra$ing mosques and churches, smashing artifacts, bulldozing archaeological sites and illegall! trafficking antiquities at a rate rarel! seen in histor!. Iraqi cultural heritage is suffering grie ous and in man! cases irre ersible harm. To pre ent this from happening, we collect and share information, research and expert knowledge, work to raise public awareness and both de elop and execute strategies to protect heritage sites and other cultural propert! through international cooperation, advocac! and technical assistance. R&SHID International e.). Postfach ++, Institute for &ncient Near -astern &rcheology Ludwig-Maximilians/Uni ersit! of "unich 0eschwister-Scholl/*lat$ + (/,1234 "unich 0erman! https566www.rashid-international.org [email protected] Copyright This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution .! International license. 8ou are free to copy and redistribute the material in an! medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for an! purpose, e en commerciall!. R&SHI( International e.). cannot re oke these freedoms as long as !ou follow the license terms. -

Bird Sites of the Osme Region 6—Birding the Palmyra Area, Syria DA MURDOCH

Bird Sites of the OSME Region 6—Birding the Palmyra area, Syria DA MURDOCH The oasis of Palmyra (Figure 1) lies in the centre of the Syrian Badia, the northern end of a vast desert that extends continuously through the Arabian peninsula to the Indian ocean. Twice a year, hundreds of millions of migrants pass along the eastern Mediterranean flyway, breeding in eastern Europe and western Asia and wintering in Africa, and these drylands constitute a formidable barrier for them. As a large oasis far into the desert, Palmyra has always attracted migrants, but until recently birders were unable to visit Syria. The situation has now changed and ecotourists are welcome; and even with limited coverage, the desert round Palmyra has emerged as one of the best birding areas in the OSME region. The recognition of Palmyra is closely linked to the discovery of its most famous bird, the Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita. After 1989, when the last birds of the colony at Birecik, Turkey, were taken into captivity (van den Berg 1989), Northern Bald Ibis was believed extinct in the eastern Mediterranean; and in 1994 it was placed on the IUCN Critically Endangered list. But in 1999, a famous local hunter, Adib al-Asaad (AA), shot and ate a large black bird that he did not recognise in the hills near Palmyra (it tasted disgusting). A few years later, by then a passionate conservationist, he leafed through an identification guide belonging to Gianluca Serra (GS) and found an illustration that matched the bird he had shot. There had been no Syrian records for 40 years but he To Jebel Abu Rigmin To Sukhne and Deir Ez-Zor Douara Arak Sed Wadi Abied To Homs Palmyra town Palmyra oasis T3 Maksam Talila Sabkhat Muh Abbaseia 10 km To Damascus Figure 1. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001 Weekly Report 57–58 — September 2-15, 2015 Michael D. Danti, Allison Cuneo, Susan Penacho, Kyra Kaercher, Katherine Burge, Mariana Gabriel, and LeeAnn Barnes Gordon Executive Summary During the reporting period, ASOR CHI documented severe damage to seven of Palmyra’s tower tombs caused by ISIL deliberate destructions using explosives. During this same period, ISIL released information on social media sites and in its magazine Dabiq on its deliberate destructions of several major buidlings at the UNESCO World Heritage Site Ancient City of Palmyra — the Baalshamin Temple and the Temple of Bel — and the Deir Mar Elian (Mar Elian Monastery). The Baalshamin Temple and Temple of Bel destructions have been verified using satellite imagery. ASOR CHI also documented new looting and other damage at the sites of Apamea and Tell Houach in Hama Governorate while under Syrian Regime control. This report also includes a special report from The Day After Protection Initiative on ISIL looting in northern Syria including details on damage to 11 sites in the Membidj area and 5 sites in the Jerablus area in Aleppo Governorate. Map of Palmyra indicating monuments intentionally damaged or destroyed during ISIL occupation (DigitalGlobe annotated by ASOR CHI; September 2, 2015) 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Heritage Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. -

The Decorated Syrian Orthodox Churches of Saddad (Syria)*

ECA 8 (2011), p. 57-82; doi: 10.2143 / ECA.8.0.2961366 The Decorated Syrian Orthodox Churches of Saddad (Syria)* Mat IMMERZEEL INTRODUCTION to investigate the expressions of a communal iden- tity among oriental Christians up till present, so From time immemorial, the mountainous region to that Saddad’s eighteenth-century murals suddenly the north of Damascus known as the Qalamun has became more relevant to my study. Unfortunately, been a bulwark of Syrian Christianity. Whereas my plans to return to the Qalamun for additional most of the Qalamun’s Christian inhabitants were research in 2011 had to be cancelled due to the Melkites, a number of communities supported the persisting unrest in Syria. Rather than delaying the Miaphysite standpoints. The pre-eminent Syrian publication of my study until further notice, Orthodox stronghold in this region was the sparsely I decided to write the present article, which, as the populated region stretching from the north-eastern reader will understand, has a provisional status. Qalamun to Homs, where they had two monaster- ies: Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi in the mountains SOME REMARKS ON SADDAD’S HISTORY east of Nebk, and Deir Mar Elian as-Sharki near Qaryatain1. One of the villages with an enduring At first sight, Saddad seems to be a place in the Miaphysite tradition is Saddad, situated in a desert middle of nowhere. Nevertheless, for centuries it landscape some 60 km to the south of Homs and was an essential stopover for travellers on their way 100 km to the north of Damascus (Pl. 1). Here, to or from Palmyra (Tadmor). -

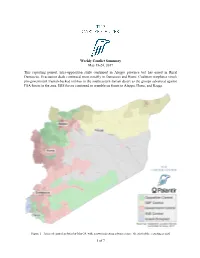

1 of 7 Weekly Conflict Summary May 18-24, 2017 This Reporting Period

Weekly Conflict Summary May 18-24, 2017 This reporting period, intra-opposition strife continued in Aleppo province but has eased in Rural Damascus. Evacuation deals continued, most notably in Damascus and Homs. Coalition warplanes struck pro-government Iranian-backed militias in the southeastern Syrian desert as the groups advanced against FSA forces in the area. ISIS forces continued to crumble on fronts in Aleppo, Homs, and Raqqa. Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by May 24, with arrows indicating advances since the start of the reporting period 1 of 7 Weekly Conflict Summary – May 18-24, 2017 Opposition Strife After weeks of clashes between Jaysh al-Islam and groups aligned with Hai’yat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, formerly al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra) in the opposition-held Eastern Ghouta pocket near Damascus, struggles between opposition forces in the area seem to have calmed down. Jaysh al-Islam fighters returned to fronts against pro-government units in Beit Nayem and launched attacks on al-Rihan neighborhood in Damascus, while Faylaq al-Rahman resumed clashes against pro-government formations in Arbin (see map below). Figure 2 – Map of areas of control around Damascus and the Eastern Ghouta by May 24 Even as Eastern Ghouta fighting quieted, new intra-opposition clashes between Faylak al-Sham against Levantine Front and the Sultan Murad Brigades erupted in the northern Aleppo countryside east of Al-Rai. On May 23, Levantine Front forces attacked and captured Faylaq al-Sham positions in Kafr Ghan, Baraghideh, and Sheikh Rih after accusing them of working with HTS. Levantine Front and Sultan Murad Brigades stated that a portion of Faylak al-Sham’s subunit, Liwa Fursan al-Thawra (formerly part of HTS sub-unit Nour al-Din al-Zenki), was harboring HTS fighters within it.