The Battle for Al Qusayr, Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Syrian Arab Republic News Focus: Syria https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria (OSES) https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/ Syrian Civil Society Voices: A Critical Part of the Political Process (In: Politically Speaking, 29 June 2021): https://bit.ly/3dYGqko Syria: a 10-year crisis in 10 figures (OCHA, 12 March 2021): https://www.unocha.org/story/syria-10-year-crisis-10-figures Secretary-General announces appointments to Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Syria Humanitarian Deconfliction System (SG/SM/20548, 21 January 2021): https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20548.doc.htm Secretary-General establishes board to investigate events in North-West Syria since signing of Russian Federation-Turkey Memorandum on Idlib (SG/SM/19685, 1 August 2019): https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19685.doc.htm Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels V Conference, 29-30 March 2021 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2021/03/29-30/ Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels IV Conference, 30 June 2020: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2020/06/30/ Third Brussels conference “Supporting the future of Syria and the region”, 12-14 March 2019: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2019/03/12-14/ Second Brussels Conference "Supporting the future of Syria and the region", 24-25 April 2018: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2018/04/24-25/ -

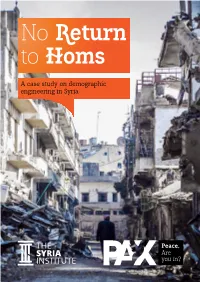

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

The Documentation of the Sectarian Massacre of Talkalakh City in Homs Governorate

SNHR is an independent, non-governmental, nonprofit, human rights organization that was founded in June 2011. SNHR is a Thursday 31 October 2013 certified source for the United Nation in all of its statistics. The Documentation of the Sectarian Massacre of Talkalakh City in Homs Governorate The documenting party: Syrian Network for Human Rights On Thursday 31 October 2013, about 11:00 pm, a group of “local committees” entered the house of an IDPs family in Al Zara village in Talkalakh city and slaugh- tered a woman and her two children with knives. The location on the map: Alaa Mameesh, the eldest son of the family, told SNHR about the slaughtering of his mother and two brothers at the hands of pro-regime forces Al Shabiha: “The family displaced from Al Zara village due to clashes between Free Army and the regime army which consists of 95% Alawites in that area. The family displaced to Talkalakh city which is controlled by the regime hoping the situation would be better there. When Al Shabiha knew that the building contains people from Al Zara village, they stormed the house and without any investigation they killed them all, my mother, my sister and my brother. My father, Fat-hi Mameesh is an officer in the regime army, he fought the Free Army in many battels. Al Shabiha haven’t asked my family about any information. They killed them only because they are IDPs from Al Zara village which is of a Sunni majority. We couldn’t identify anything about their corpses or whether they buried them or not because they banned anyone from Al Zara village to enter Talkalakh city” 1 www.sn4hr.org - [email protected] The victims’ names: The mother, Elham Jardi/ Homs/ Al Zara village/ (Um Alaa) Hanadi Fat-hi Mameesh, 19-year-old/ Homs/ Al Zara village Mohammad Fat-hi Mameesh, 17-year-old/ Al Zara village. -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

The Alawite Dilemma in Homs Survival, Solidarity and the Making of a Community

STUDY The Alawite Dilemma in Homs Survival, Solidarity and the Making of a Community AZIZ NAKKASH March 2013 n There are many ways of understanding Alawite identity in Syria. Geography and regionalism are critical to an individual’s experience of being Alawite. n The notion of an »Alawite community« identified as such by its own members has increased with the crisis which started in March 2011, and the growth of this self- identification has been the result of or in reaction to the conflict. n Using its security apparatus, the regime has implicated the Alawites of Homs in the conflict through aggressive militarization of the community. n The Alawite community from the Homs area does not perceive itself as being well- connected to the regime, but rather fears for its survival. AZIZ NAKKASH | THE ALAWITE DILEMMA IN HOMS Contents 1. Introduction ...........................................................1 2. Army, Paramilitary Forces, and the Alawite Community in Homs ...............3 2.1 Ambitions and Economic Motivations ......................................3 2.2 Vulnerability and Defending the Regime for the Sake of Survival ..................3 2.3 The Alawite Dilemma ..................................................6 2.4 Regime Militias .......................................................8 2.5 From Popular Committees to Paramilitaries ..................................9 2.6 Shabiha Organization ..................................................9 2.7 Shabiha Talk ........................................................10 2.8 The -

Security Council Distr.: General 16 June 2016 English Original: Arabic

United Nations S/2016/534 Security Council Distr.: General 16 June 2016 English Original: Arabic Identical letters dated 13 June 2016 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council On instructions from my Government, I should like to draw your attention to the following information regarding terrorist acts committed by armed terrorist groups active in Syrian territory during the month of May 2016: 3 May • Some 19 people were killed and more than 65 others were injured, including women and children, when armed terrorist groups fired dozens of shells at Dubayt Hospital and other neighbourhoods in the city of Aleppo and its countryside. • A civilian was killed when a mortar shell landed in Khan al-Shaykh in Rif Dimashq. • A mortar shell landed in Dar‘a, injuring a civilian. • A mortar shell landed in the Tahtuh neighbourhood in Dayr al-Zawr, injuring a civilian. 4 May • Four civilians were killed and more than 15 others were injured, including women and children, when dozens of shells fell in several neighbourhoods of the city of Aleppo and its countryside. • The terrorist Nusrah Front organization perpetrated a massacre in the village of Khuwayn in Idlib, killing 15 civilians, including four children. 5 and 6 May • On Thursday, 12 civilians were killed and 40 injured when terrorist explosions occurred in the city of Upper Mukharram in the Homs countryside. • Terrorist groups fired several shells at the Maydan neighbourhood in Aleppo, killing one civilian and injuring another. Material damage was caused. -

Syria Drought Response Plan

SYRIA DROUGHT RESPONSE PLAN A Syrian farmer shows a photo of his tomato-producing field before the drought (June 2009) (Photo Paolo Scaliaroma, WFP / Surendra Beniwal, FAO) UNITED NATIONS SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC - Reference Map Elbistan Silvan Siirt Diyarbakir Batman Adiyaman Sivarek Kahramanmaras Kozan Kadirli TURKEY Viransehir Mardin Sanliurfa Kiziltepe Nusaybin Dayrik Zakhu Osmaniye Ceyhan Gaziantep Adana Al Qamishli Nizip Tarsus Dortyol Midan Ikbis Yahacik Kilis Tall Tamir AL HASAKAH Iskenderun A'zaz Manbij Saluq Afrin Mare Al Hasakah Tall 'Afar Reyhanli Aleppo Al Bab Sinjar Antioch Dayr Hafir Buhayrat AR RAQQA As Safirah al Asad Idlib Ar Raqqah Ash Shaddadah ALEPPO Hamrat Ariha r bu AAbubu a add D Duhuruhur Madinat a LATAKIA IDLIB Ath Thawrah h Resafa K l Ma'arat a Haffe r Ann Nu'man h Latakia a Jableh Dayr az Zawr N El Aatabe Baniyas Hama HAMA Busayrah a e S As Saiamiyah TARTU S Masyaf n DAYR AZ ZAWR a e n Ta rtus Safita a Dablan r r e Tall Kalakh t Homs i Al Hamidiyah d Tadmur E e uphrates Anah M (Palmyra) Tripoli Al Qusayr Abu Kamal Sadad Al Qa’im HOMS LEBANON Al Qaryatayn Hadithah BEYRUT An Nabk Duma Dumayr DAMASCUS Tyre DAMASCUS QQuneitrauneitra Ar Rutbah QUNEITRA Haifa Tiberias AS SUWAIDA IRAQ DAR’A Trebil ISRAELI S R A E L DDarar'a As Suwayda Irbid Jenin Mahattat al Jufur Jarash Nabulus Al Mafraq West JORDAN Bank AMMAN JERUSALEM Bayt Lahm Madaba SAUDI ARABIA Legend Elevation (meters) National capital 5,000 and above First administrative level capital 4,000 - 5,000 Populated place 3,000 - 4,000 International boundary 2,500 - 3,000 First administrative level boundary 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 050100150 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 km 600 - 800 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material 400 - 600 on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal 200 - 400 status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Complaint for of the Estate of MARIE COLVIN, and Extrajudicial Killing, JUSTINE ARAYA-COLVIN, Heir-At-Law and 28 U.S.C

Case 1:16-cv-01423 Document 1 Filed 07/09/16 Page 1 of 33 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CATHLEEN COLVIN, individually and as Civil No. __________________ parent and next friend of minors C.A.C. and L.A.C., heirs-at-law and beneficiaries Complaint For of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, and Extrajudicial Killing, JUSTINE ARAYA-COLVIN, heir-at-law and 28 U.S.C. § 1605A beneficiary of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, c/o Center for Justice & Accountability, One Hallidie Plaza, Suite 406, San Francisco, CA 94102 Plaintiffs, v. SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC, c/o Foreign Minister Walid al-Mualem Ministry of Foreign Affairs Kafar Soussa, Damascus, Syria Defendant. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Cathleen Colvin and Justine Araya-Colvin allege as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. On February 22, 2012, Marie Colvin, an American reporter hailed by many of her peers as the greatest war correspondent of her generation, was assassinated by Syrian government agents as she reported on the suffering of civilians in Homs, Syria—a city beseiged by Syrian military forces. Acting in concert and with premeditation, Syrian officials deliberately killed Marie Colvin by launching a targeted rocket attack against a makeshift broadcast studio in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Case 1:16-cv-01423 Document 1 Filed 07/09/16 Page 2 of 33 Homs where Colvin and other civilian journalists were residing and reporting on the siege. 2. The rocket attack was the object of a conspiracy formed by senior members of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (the “Assad regime”) to surveil, target, and ultimately kill civilian journalists in order to silence local and international media as part of its effort to crush political opposition. -

Exhibition Checklist I. Creating Palmyra's Legacy

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST 1. Caravan en route to Palmyra, anonymous artist after Louis-François Cassas, ca. 1799. Proof-plate etching. 15.5 x 27.3 in. (29.2 x 39.5 cm). The Getty Research Institute, 840011 I. CREATING PALMYRA'S LEGACY Louis-François Cassas Artist and Architect 2. Colonnade Street with Temple of Bel in background, Georges Malbeste and Robert Daudet after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 16.9 x 36.6 in. (43 x 93 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 58. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 1 3. Architectural ornament from Palmyra tomb, Jean-Baptiste Réville and M. A. Benoist after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 18.3 x 11.8 in. (28.5 x 45 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 137. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 4. Louis-François Cassas sketching outside of Homs before his journey to Palmyra (detail), Simon-Charles Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 20. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 5. Louis-François Cassas presenting gifts to Bedouin sheikhs, Simon Charles-Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41 cm). -

The Qusayr Rules: the Syrian Regime's Changing Way of War by Jeffrey White

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2082 The Qusayr Rules: The Syrian Regime's Changing Way of War by Jeffrey White May 31, 2013 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jeffrey White Jeffrey White is an adjunct defense fellow at The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of the Levant and Iran. Brief Analysis Given the regime's renewed offensive capabilities, delaying foreign military assistance any further is a recipe for more rebel defeats. he ongoing battle in and around al-Qusayr city in Syria's Homs province is not just another clash. It is a full- T scale fight with major significance for the war, similar to the battle for Aleppo in summer 2012. Despite determined rebel resistance, this is a battle the regime must win. And given its current advantages, Damascus most likely will win. Al-Qusayr is already testing the regime's developing capabilities and those of its allies, especially Hezbollah. Perhaps more important, Bashar al-Assad's forces seem to be establishing a set of "Qusayr rules" that will shape how they conduct the war in the period ahead. SIGNIFICANCE T he battle for al-Qusayr is important for many reasons. The area dominates the southern route through Homs province to the coast, a stronghold of the regime's Shiite Alawite supporters. It also controls the southern approaches to Homs city, where regime forces continue to struggle. In addition to threatening Shiite villages in the area, rebel control of al-Qusayr hinders regime access to Lebanon's Beqa Valley while facilitating the cross-border movement of arms to rebels in west central Syria.