Particle W. Anthony Davis, Piano with Electronics. Included on Middle Passage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klassisk Sommer På Ramme

4.7 4.7 Birgitta Elisa Klassisk sommer Oftestad på Ramme Music for a While 11.7 11.7 4. juli—15. august 4.7 Audun Sand- vik Sveinung kl. 15:00 Bjelland 18.7 Catherine 4.7 Åpningskonsert med stjerneduo Bullock-Bukkøy i musikk av Schumann og Brahms 18.7 Birgitta Elisa Oftestad, cello / Sveinung Bjelland, piano 18.7 kl. 19:00 Etterspill med Music for a While Sjangeroverskridende, improvisatorisk lekne og tidløse tolkninger av det klassiske sangrepertoaret. Arve Tellefsen Eir Inderhaug Ola B. Johannessen Tora Augestad, vokal / Trygve Brøske, piano / Martin Taxt, tuba / Rolf-Erik Nystrøm, saksofon / Pål Hausken, perkusjon / Kjetil Jens Harald 18.7 25.7 8.8 Stian Carstensen, accordion, pedal-steel & banjo Bjerkestrand Bratlie kl. 15:00 11.7 Brahms’ og Beethovens store kammermusikk Birgitte Stærnes, fiolin / Catherine Bullock-Bukkøy, bratsj / Audun Sandvik, cello / Thormod Rønning Kvam, piano 1.8 15.8 Sonoro Strykekvartett kl. 19:00 8.8 Etterspill med MEER Orkestral pop, klassisk musikk og progressiv rock i ny drakt. Johanne Margrethe Kippersund Nesdal, vokal / Knut Kippersund Nesdal, vokal / Eivind Strømstad, gitar / Åsa Ree, fiolin / Ingvild Nordstoga Eide, bratsj / Ole Gjøstøl, piano / Pierre Duo Volt & Potenza Xhonneux Bukkene Bruse Morten Strypet, bass / Mats Lillehaug, trommer kl. 15:00 kl. 15:00 18.7 Griegs Haugtussa med ny sammensetning 8.8 Sonoro Strykekvartett spiller av Garborgs tekster Grieg, Shaw, Britten & Sæverud Ola B. Johannessen, skuespiller / Eir Inderhaug, sopran / Daniel Goldin, fiolin / Martha-Pil Neumer, fiolin / Thormod Rønning Kvam, piano Tuva Odland, bratsj / Hedda Aadland, cello I samarbeid med Oslo Quartet Series og satsningen Ung Kvartettserie. -

Piano Recital Prize and Arnold Schoenberg

1 Welcome to Summer 2015 at the RNCM As Summer 2015 approaches, the RNCM Our orchestral concerts are some of our most prepares for one of its most monumental concerts colourful ones, and more fairytales come to life to date. This is an historic moment for the College with Kodaly’s Hary Janos and Bartók’s Miraculous and I am honoured and thrilled to be welcoming Mandarin as well as with an RNCM Family Day, Krzysztof Penderecki to conduct the UK première where we join forces with MMU’s Manchester of his magnificent Seven Gates of Jerusalem Children’s Book Festival to bring together a feast at The Bridgewater Hall in June. This will be of music and stories for all ages with puppetry, the apex of our celebration of Polish music, story-telling, live music and more. RNCM Youth very kindly supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Perform is back on stage with Bernstein’s award- Institute, as part of the Polska Music programme. winning musical On the Town, and our Day of Song brings the world of Cabaret to life. In a merging of soundworlds, we create an ever-changing kaleidoscope of performances, We present music from around the world with presenting one of our broadest programmes to Taiko Meantime Drumming, Taraf de Haïdouks, date. Starting with saxophone legend David Tango Siempre, fado singer Gisela João and Sanborn, and entering the world of progressive singer songwriters Eddi Reader, Thea Gilmore, fusion with Polar Bear, the jazz programme at Benjamin Clementine, Raghu Dixit, Emily Portman the RNCM collaborates once more with Serious and Mariana Sadovska (aka ‘The Ukranian as well as with the Manchester Jazz Festival to Bjork’). -

Programme 2009 the Abel Prize Ceremony 19 May 2009 Procession Accompanied by the “Abel Fanfare” Music: Klaus Sandvik

Programme 2009 The Abel Prize Ceremony 19 May 2009 Procession accompanied by the “Abel Fanfare” Music: Klaus Sandvik. Performed by three musicians from the Staff Band of the Norwegian Defence Forces Their Majesties King Harald and Queen Sonja enter the hall Soroban Arve Henriksen (trumpet) (Music: Arve Henriksen) Opening by Øyvind Østerud President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Eg veit i himmerik ei borg Trio Mediæval, Arve Henriksen (Norwegian folk tune from Hallingdal, arr. Linn A. Fuglseth) The Abel Prize Award Ceremony Professor Kristian Seip Chairman of the Abel Committee The Committee’s citation His Majesty King Harald presents the Abel Prize to Mikhail Leonidovich Gromov Acceptance speech by Mikhail Leonidovich Gromov Closing remarks by Professor Øyvind Østerud President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Till, till Tove Trio Mediæval, Arve Henriksen, Birger Mistereggen (percussion) (Norwegian folk tune from Vestfold, arr. Tone Krohn) Their Majesties King Harald and Queen Sonja leave the hall Procession leaves the hall Other guests leave the hall when the procession has left to a skilled mathematics teacher in the upper secondary school is called after Abel’s own Professor Øyvind Østerud teacher, Bernt Michael Holmboe. There is every reason to remember Holmboe, who was President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Abel’s mathematics teacher at Christiania Cathedral School from when Abel was 16. Holmboe discovered Abel’s talent, inspired him, encouraged him, and took the young pupil considerably further than the curriculum demanded. He pointed him to the professional literature, helped Your Majesties, Excellencies, dear friends, him with overseas contacts and stipends and became a lifelong colleague and friend. -

QUASIMODE: Ike QUEBEC

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ QUASIMODE: "Oneself-Likeness" Yusuke Hirado -p,el p; Kazuhiro Sunaga -b; Takashi Okutsu -d; Takahiro Matsuoka -perc; Mamoru Yonemura -ts; Mitshuharu Fukuyama -tp; Yoshio Iwamoto -ts; Tomoyoshi Nakamura -ss; Yoshiyuki Takuma -vib; recorded 2005 to 2006 in Japan 99555 DOWN IN THE VILLAGE 6.30 99556 GIANT BLACK SHADOW 5.39 99557 1000 DAY SPIRIT 7.02 99558 LUCKY LUCIANO 7.15 99559 IPE AMARELO 6.46 99560 SKELETON COAST 6.34 99561 FEELIN' GREEN 5.33 99562 ONESELF-LIKENESS 5.58 99563 GET THE FACT - OUTRO 1.48 ------------------------------------------ Ike QUEBEC: "The Complete Blue Note Forties Recordings (Mosaic 107)" Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded July 18, 1944 in New York 34147 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.35 Blue Note 6507 37805 BLUE HARLEM 4.33 Blue Note 37 37806 INDIANA 3.55 Blue Note 38 39479 SHE'S FUNNY THAT WAY 4.22 --- 39480 INDIANA 3.53 Blue Note 6507 39481 BLUE HARLEM 4.42 Blue Note 544 40053 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.36 Blue Note 37 Jonah Jones -tp; Tyree Glenn -tb; Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Oscar Pettiford -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded September 25, 1944 in New York 37810 IF I HAD YOU 3.21 Blue Note 510 37812 MAD ABOUT YOU 4.11 Blue Note 42 39482 HARD TACK 3.00 Blue Note 510 39483 --- 3.00 prev. unissued 39484 FACIN' THE FACE 3.48 --- 39485 --- 4.08 Blue Note 42 Ike Quebec -ts; Napoleon Allen -g; Dave Rivera -p; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. -

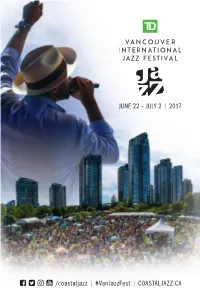

Jazz-Fest-2017-Program-Guide.Pdf

JUNE 22 – JULY 2 | 2017 /coastaljazz | #VanJazzFest | COASTALJAZZ.CA 20TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017 181 CHAN CENTRE PRESENTS SERIES The Blind Boys of Alabama with Ben Heppner I SEP 23 The Gloaming I OCT 15 Zakir Hussain and Dave Holland: Crosscurrents I OCT 28 Ruthie Foster, Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Carrie Rodriguez I NOV 8 The Jazz Epistles: Abdullah Ibrahim and Hugh Masekela I FEB 18 Lila Downs I MAR 10 Daymé Arocena and Roberto Fonseca I APR 15 Circa: Opus I APR 28 BEYOND WORDS SERIES Kate Evans: Threads I SEP 29 Tanya Tagaq and Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory I MAR 16+17 SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE MAY 2 DAYMÉ AROCENA THE BLIND BOYS OF ALABAMA HUGH MASEKELA TANYA TAGAQ chancentre.com Welcome to the 32nd Annual TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival TD is pleased to bring you the 2017 TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival, a widely loved and cherished world-class event celebrating talented and culturally diverse artists from Canada and around the world. In Vancouver, we share a love of music — it is a passion that brings us together and enriches our lives. Music is powerful. It can transport us to faraway places or trigger a pleasant memory. Music is also one of many ways that TD connects with customers and communities across the country. And what better way to come together than to celebrate music at several major music festivals from Victoria to Halifax. ousands of fans across British Columbia — including me — look forward to this event every year. I’m excited to take in the music by local and international talent and enjoy the great celebration this festival has to o er. -

Per Endre Jakobsen.Pdf (526.5Kb)

Masteroppgave i ut¿vende musikk Fakultet for kunstfag H¿gskolen i Agder - Vren 2007 Visuell orientering som metode for gitarspill Per Endre Jakobsen Visuell orientering som metode for gitarspill Innholdsfortegnelse 1.0 Innledning _______________________________________________________1 1.1 Bakgrunn for temavalg ________________________________________________1 1.2 Formål ______________________________________________________________1 1.3 Problemstilling og avgrensninger ________________________________________1 2.0 Valg av metoder og teorier___________________________________________2 3.0 Musikerkoder og fagbegrep__________________________________________3 3.1 Visuell ______________________________________________________________3 3.2 Metode ______________________________________________________________4 3.3 Språk _______________________________________________________________4 3.4 Teori________________________________________________________________4 3.5 Gitar________________________________________________________________4 3.6 Musikk ______________________________________________________________4 3.7 Forskning____________________________________________________________5 4.0 Tonene på gitaren _________________________________________________5 4.1 Oktaver _____________________________________________________________7 4.2 C major _____________________________________________________________9 4.3 D dorisk/ C major_____________________________________________________9 4.4 E frygisk/C major ____________________________________________________10 -

Icp Orkest Beleidsplan 2017

ICP ORKEST BELEIDSPLAN 2017 – 2020 BELEIDSPLAN 2017 - 2020 INHOUD Hoofdstuk 1 Korte typering van het ICP 2 Hoofdstuk 2 Artistieke uitgangspunten, signatuur en beschrijving activiteiten 3 Hoofdstuk 3 Plaats in het veld 9 Hoofdstuk 4 Ondernemerschap 10 Hoofdstuk 5 Spreiding 14 Hoofdstuk 6 Bijdrage talentontwikkeling 15 Hoofdstuk 7 Toelichting op de begroting, dekkingsplan en Kengetallen 17 -1- Hoofdstuk 1 Korte typering van het ICP “(…)The Instant Composers Pool Orchestra, from Amsterdam, mixing swing and bop (…) with conducted improvisations and free jazz (…), has some idiosyncratic and brilliant soloists (…), they are scholars and physical comedians, critics and joy-spreaders.” (Ben Ratliff, New York Times reviewing group’s January 2015 performance) Missie en hoofddoelstelling ICP is de afkorting van de naam Instant Composers Pool, een ensemble dat in 1967 is opgericht door pianist/componist Misha Mengelberg, drummer Han Bennink en klarinettist/saxofonist/componist Willem Breuker. De term ‘instant composing’ is gemunt door Mengelberg en staat voor een specifieke vorm van muzikaal denken en handelen op basis van improvisatie. In instant composing is improviseren een vorm van ter plekke componeren. Dit proces is mede bepalend voor de bijzondere positie van ICP in de eigentijdse muziek. De methode ICP werkt alleen als de musici meester zijn op hun instrument en met elkaar tot in hun diepste wezen verbonden zijn. De huidige bezetting speelt inmiddels bijna 25 jaar in dezelfde samenstelling. Om beurten stelt een van de musici een setlist samen voor aanvang van het concert. (Voorbeeld setlist (handschrift Han Bennink): zie hieronder) Voor de instant composing-methode draagt een aantal orkestleden stukken of thema’s aan, in notenschrift uitgewerkt: soms niet mee dan een paar akkoorden, soms in uitgebreide arrangementen en varianten daartussen, die– op het podium – bedacht en gespeeld worden. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

L'invention Musicale Face À La Nature Dans Grizzly

L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog Vincent Deville To cite this version: Vincent Deville. L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog. Revue musicale OICRM, Observatoire interdisciplinaire de création et de recherche en musique, 2018, 5 (n°1), s.p. hal-02133197v1 HAL Id: hal-02133197 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02133197v1 Submitted on 17 May 2019 (v1), last revised 15 Jul 2019 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog Vincent Deville Résumé Quand le cinéaste allemand Werner Herzog réalise ou produit trois documentaires sur la création et l’enregistrement de la musique de trois de ses films entre 2005 et 2011, il effectue un double geste de révélation et d’incarnation : les notes nous deviennent visibles à travers le corps des musiciens. -

Dossier De Presse

rec tdic iph cseé uqp, luoJ Dossier de presse ieuo e"rn rAMH qka uas iDrs laie stfl eral saS tb cir oJea naev cvta oaei c"nl t,cl éqo ,uma aipv ulae tegc onp bril aeé pgdt tieh isDo sthr érae Fefd oae uvr reYt tcoi hlus West ose rmes lufd http://www.amr-geneve.ch/amr-jazz-festival dseo (itn Compilation des groupes du festival disponible sur demande qcPt uiaB Contact médias: Leïla Kramis [email protected], tél: 022 716 56 37/ 078 793 50 72 aeo tnla AMR / Sud des Alpes rsob 10, rue des Alpes, 1201 Genève iAFa T + 41 22 716 56 30 / F + 41 22 716 56 39 èbrM mdea eosa 35e AMR Jazz Festival – dossier de presse 1 mul oM., nbH Table des matières I. L’AMR EN BREF....................................................................................................................................... 3 II. SURVOL DES CONCERTS..................................................................................................................... 4 III. DOSSIERS ARTISTIQUES..................................................................................................................... 5 PARALOG.............................................................................................................................................. 5 JOE LOVANO QUARTET...................................................................................................................... 7 PLAISTOW........................................................................................................................................... 10 J KLEBA............................................................................................................................................ -

Bjørnsonfestivalen

bjørnsonfestivalen the norwegian festival of international literature Aina Villanger Hennings Bergsvåg Hedvig Rossbach Wist Mette Karlsvik Ann Kavli Moten Strøksnes Alain Mabanckou Teatret Vårt Arnhild Skre Henrik Svensen Morten Harper Hanne Frey husø Thomas Lundbo Bendik Kaltenborn Sara Mats Azmed Rasmussen Hanne Nabintu Herland Per Edgar Kokkvold Nina Witoszek Dechen Pemba Chungdak Koren Khaled Khalifa Tora Augestad Stian Carstensen Mathias Eick Martin Taxt Pål Hausken Ola Kvernberg Paal-Helge Haugen Inger Bråtveit Carl Morten Amundsen Vivi Sunde Jo Inge Nes Øystein Sandbukt Peter Wergeni Audun Skorgen Erik Fostervoll Edvard Hoem Hilde Brunsvik Dag-Filip Roaldset Solveig Slettahjell Morten Qvenild Karen Bit Vejle (Isaksen Tor Ivar Forsland) Jon Severud Tove Nilsen PROGRAM BJØRNSONFESTIVALEN 2012 MOLDE DAG KL PROGRAMPOST MEDVIRKENDE STED bjørnsonfestivalen Onsdag 29.08 15.00 - 15.40 Åpning av festivalen. folketale+kunstneriske innslag+ Sara Mats Azmeh Rasmussen Alexandraparken utdeling av Bjørnsonstipendet 16.00 - 17.00 Om Joseph Conrad og Mørkets hjerte Jeremy Hawthorn Storyville the norwegian festival of international literature 19.00- 20.00 Utenlandsk skjønnliteratur Alain Mabanckou og Marguerite Abouet Storyville 20.00-21.30 Generalprøve “TIL KONGO!” Teatret Vårt Teatret Vårt 20.00 - 21.00 Foredrag om Brecth? Vigdis Hjort ?? Molde Bibliotek VELKOMMEN TIL Alt som er i himmelen Karl Ove Knausgård og Thomas Wågström Teatret Vårt 22.00 Åpning av festivalutstilling. Festivalutstiller, diktopplesing ved Ann Kavli? Plassen kulturelle innslag og bevertning BJØRNSONFESTIVALEN 2012 Torsdag 30.08 08.00 - 08.30 Fole god bok til frokost Erlend Nødtvedt Fole Godt Formiddag Skolebesøk på 5. trinn Marit Nicolaisen Ansvarlig utgiver C. Uspiont elabunc venatus? Nam Formiddag Skolebesøk i videregående Jørn Lier Horst nondiur interei furive, Catus Bjørnsonfestivalen 11.00 - 15.00 Seminar: Totalitære regimer Khaled Khalifa, Srdja Popovic, Lina Ben Mehni, Teatret Vårt vissent erfeciam prox ni faceps, Dechen Pemba, Elizabeth Baumann, Jonas Gahr Støre.