A Validation of Voter's Political Trust in Mokokchung District (Nagaland)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAGALAND Basic Facts

NAGALAND Basic Facts Nagaland-t2\ Basic Facts _ry20t8 CONTENTS GENERAT INFORMATION: 1. Nagaland Profile 6-7 2. Distribution of Population, Sex Ratio, Density, Literacy Rate 8 3. Altitudes of important towns/peaks 8-9 4. lmportant festivals and time of celebrations 9 5. Governors of Nagaland 10 5. Chief Ministers of Nagaland 10-11 7. Chief Secretaries of Nagaland II-12 8. General Election/President's Rule 12-13 9. AdministrativeHeadquartersinNagaland 13-18 10. f mportant routes with distance 18-24 DEPARTMENTS: 1. Agriculture 25-32 2. Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services 32-35 3. Art & Culture 35-38 4. Border Afrairs 39-40 5. Cooperation 40-45 6. Department of Under Developed Areas (DUDA) 45-48 7. Economics & Statistics 49-52 8. Electricallnspectorate 52-53 9. Employment, Skill Development & Entrepren€urship 53-59 10. Environment, Forests & Climate Change 59-57 11. Evalua6on 67 t2. Excise & Prohibition 67-70 13. Finance 70-75 a. Taxes b, Treasuries & Accounts c. Nagaland State Lotteries 3 14. Fisheries 75-79 15. Food & Civil Supplies 79-81 16. Geology & Mining 81-85 17. Health & Family Welfare 85-98 18. Higher & Technical Education 98-106 19. Home 106-117 a, Departments under Commissioner, Nagaland. - District Administration - Village Guards Organisation - Civil Administration Works Division (CAWO) b. Civil Defence & Home Guards c. Fire & Emergency Services c. Nagaland State Disaster Management Authority d. Nagaland State Guest Houses. e. Narcotics f. Police g. Printing & Stationery h. Prisons i. Relief & Rehabilitation j. Sainik Welfare & Resettlement 20. Horticulture tl7-120 21. lndustries & Commerce 120-125 22. lnformation & Public Relations 125-127 23. -

Government of Nagaland

Government of Nagaland Contents MESSAGES i FOREWORD viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT x VISION STATEMENT xiv ACRONYMS xvii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 5 2. AGRICULTURE AND ALLIED SECTORS 12 3. EmPLOYMENT SCENARIO IN NAGALAND 24 4. INDUSTRIES, INDUSTRIALIZATION, TRADE AND COMMERCE 31 5. INFRASTRUCTURE AND CONNECTIVITY 42 6. RURAL AND URBAN PERSPECTIVES 49 7. EDUCATION, HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES 56 8. GENDER MAINSTREAMING 76 9. REGIONAL DISPARITIES 82 10. GOVERNANCE 93 11. FINANCING THE VISION 101 12. CONCLUSION 107 13. APPENDIX 117 RAJ BHAVAN Kohima-797001 December 03,2016 Message I value the efforts of the State Government in bringing out documentation on Nagaland Vision Document 2030. The Vision is a destination in the future and the ability to translate the Vision through Mission, is what matters. With Vision you can plan but with Mission you can implement. You need conviction to translate the steps needed to achieve the Vision. Almost every state or country has a Vision to propel the economy forward. We have seen and felt what it is like to have a big Vision and many in the developing world have been inspired to develop a Vision for their countries and have planned the way forward for their countries to progress. We have to be a vibrant tourist destination with good accommodation and other proper facilities to showcase our beautiful land and cultural richness. We need reformation in our education system, power and energy, roads and communications, etc. Our five Universities have to have dialogue with Trade & Commerce and introduce academic courses to create wealth out of Natural Resources with empowered skill education. -

A REGRESSION ANALYSIS on MARKETED SURPLUS of CABBAGE in MOKOKCHUNG and WOKHA DISTRICTS of NAGALAND Sashimatsung1 and Giribabu M2

Available Online at http://www.recentscientific.com International Journal of Recent Scientific International Journal of Recent Scientific Research Research Vol. 6, Issue, 7, pp.5225-5228, July, 2015 ISSN: 0976-3031 RESEARCH ARTICLE A REGRESSION ANALYSIS ON MARKETED SURPLUS OF CABBAGE IN MOKOKCHUNG AND WOKHA DISTRICTS OF NAGALAND Sashimatsung1 and Giribabu M2 1 2 Doctoral Fellow, Nagaland University, Lumami ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACTAssistant Professor Nagaland University, Lumami Article History: Longkhum and Soku villages under Mokokchung and Wokha districts of Nagaland is purposively selected Received 14th, June, 2015 in the present study to estimate the marketable and marketed surplus of cabbage, and regressed the factors Received in revised form 23th, determining marketed surplus in the two districts of Nagaland. The study found out that average June, 2015 production of cabbage is higher in Longkhum village thus percentage of marketed surplus is 86.38%; while Accepted 13th, July, 2015 the actual quantity marketed in Soku village is concluded to be 66.49% comparatively lower than their Published online 28th, counterpart village. This is mostly due to their high retention purpose and post-harvest loss. Further, July, 2015 regression results with and without dummy variables reveal production the prominent factor for increase marketed surplus in both the districts of Nagaland. Key words: Nagaland, cabbage, marketable surplus, marketed surplus, regression Copyright © Sashimatsung and Giribabu M., This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properlyINTRODUCTION cited. after meeting farms requirement for family consumption, needs for seeds and feeds, payment in kind or gift to labours, artisans, Mokokchung district covers an area of 1,615 sq. -

Text Set Mkg 2040.Cdr

VISION MOKOKCHUNG 2040 A collaboration between the Mokokchung QQC Planning & Organising Committee and the Citizens of Mokokchung. Prepared by; Mayangnokcha Award Trust. Published by Mokokchung District Art & Culture Council (MDACC) On behalf of the people of Mokokchung 300 copies 2019 Printed at Longpok Offset Press, Mokokchung VISION MOKOKCHUNG 2040 Contents Acknowledgements Foreword Preface Executive Summary Introduction …………………………………..………….…………………. 5 Vision Mokokchung 2040 ……………………………………………... 7 Core Values of Vision Mokokchung 2040 ……………………... 8 The Foundation of Vision Mokokchung 2040 ……..…………... 9 Economic Development Model ………………………….…………… 13 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………….. 22 MAT Position Papers. Papers from Resource Persons. Papers from Department & NGOs. Transcribes. VISION MOKOKCHUNG 2040 Acknowledgements Over the years, there have been discussions and isolated papers or documents for Mokokchung in terms of development and related issues. There are also Plan documents for development of various sectors by different Government Departments. We also appreciate that the Concerned Citizens Forum of Mokokchung (CCFM), had earlier brought out documents on their Vision of Mokokchung and its development. But a comprehensive Vision document for Mokokchung in this format is perhaps the first of its kind, and for this, we wish to place on record our appreciation to the Mokokchung QQC Planning and Organising Committee and the District Administration for the initiative and unstinted support. Mokokchung District Art & Culture Council (MDACC), who did all the legwork, liaising and various arrangements. All India Radio (AIR) Mokokchung, for giving wide publicity and producing local programmes on the theme, social media group – I Love Mokokchung (ILM), and many more. Countless individuals have taken the trouble to give their personal views and opinions, well-wishers, and many more others whose contributions havebeen immense. -

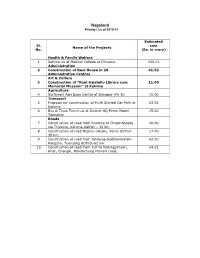

Nagaland Priority List of 2010-11

Nagaland Priority List of 2010-11 Estimated Sl. cost Name of the Projects No. (Rs. in crore) Health & Family Welfare 1 Setting up of Medical College at Dimapur 340.22 Administration 2 Construction of Rest House in 28 41.52 Administrative Centres Art & Culture 3 Construction of “Rani Gaidinliu Library cum 11.00 Memorial Museum” at Kohima Agriculture 4 Northeast Agri Expo Centre at Dimapur (Ph-II) 15.00 Transport 5 Proposal for construction of Multi Storied Car Park at 53.05 Kohima 6 Bus & Truck Terminus at District HQ Peren Model 15.00 Township Roads 7 Construction of road from Rusoma to Chiephobozou 40.00 via Thizama, Kohima district – 32 km 8 Construction of road Hebron-Jalukie, Peren district- 17.00 20 km 9 Construction of road from Jendang-Saddle-Noklak- 62.00 Pangsha, Tuensang district-62 km 10 Construction of road from Tuli to Molungyimsen, 44.01 Khar, Changki, Mokokchung Mariani road, Estimated Sl. cost Name of the Projects No. (Rs. in crore) Mokokchung District 51 km 11 Widening & Improvement of approach road from 10.00 Alongchen, Impur to Khar via Mopungchuket, Mokokchung district – 15 km 12 Construction of road Kohima to Leikie road junction 10.00 to Tepuiki to Barak, Inter-district road-10 km (MDR) Ph-III 13 Construction of road from Lukhami BRO junction to 90.00 Seyochung Tizu bridge on Satoi road, Khuza, Phughe, Chozouba State Highway junction, Inter- district road- 90 km (ODR) 14 Improvement & Upgradation of road from 5.40 Border Road to Changlangshu, Mon District-19 km 15 Construction of road from Pang to Phokphur via 12.44 -

Epiphytic Bryophytes on Thuja Orientalis in Nagaland, North-Eastern India

Bangladesh J. Plant Taxon. 18(2): 163-167, 2011 (December) © 2011 Bangladesh Association of Plant Taxonomists EPIPHYTIC BRYOPHYTES ON THUJA ORIENTALIS IN NAGALAND, NORTH-EASTERN INDIA * 1 POOJA BANSAL, VIRENDRA NATH AND S.K. CHATURVEDI Bryology Laboratory, National Botanical Research Institute, Lucknow 226 001, India Keywords: Epiphytic bryophytes; Thuja orientalis; Nagaland; India. Abstract A survey of bryophyte diversity in district Mokokchung (Nagaland) has brought to light an unexpectedly rich bryophyte flora, including several interesting species to Nagaland. The tree species Thuja orientalis Linn. growing in Nagaland, luxuriantly covered by epiphytic bryophytes with wide range of diversity. The samplings were made from tree base up to canopy as well as abaxial and adaxial side of the tree. Investigation has revealed twelve species of mosses represented to eight families belonging to the genus Brachymenium Schwaegr., Plagiothecium B.S.G., Entodontopsis Broth., Entodon C. Muell., Erythrodontium Hamp., Fabronia Raddi, Regmatodon Brid., Floribundaria Fleisch. and Hyophila Brid., four species of hepatics belonging to two families and two genera Frullania Raddi and Lejeunea Libert compose the corticolous bryophyte vegetation of Thuja orientalis in some of the localities of Nagaland, North-east region of India. The richness and diversity of bryophytes on Thuja tree bark have been assessed for the first time. Introduction Thuja orientalis Linn. is a distinct species of densely branched evergreen coniferous tree in the cypress family Cuprassaceae and is widely distributed in China, Korea, Japan, Iran and India. The trees are conical shaped, slow growing, 5-8 m tall and 3 m wide. Thuja orientalis is widely used as an ornamental tree in homeland, where it is associated with long life and vitality, as well as elsewhere in temperate climates. -

1308 Part a Dchb Longle

A PHOM WARRIOR CONTENTS Pages Foreword 1 Preface 4 Acknowledgements 5 History and scope of the District Census Hand Book 6 Brief history of the district 8 Analytical note i. Physical features of the district 11 ii. Census concepts iii. Non-Census concepts iv. 2011 Census findings v. Brief analysis of PCA data based on inset tables 1-35 vi. Brief analysis of the Village Directory and Town Directory data based on inset tables 36-45 vii. Major social and cultural events viii. Brief description of places of religious importance, places of tourist interest etc ix. Major characteristics of the district x. Scope of Village and Town Directory-column heading wise explanation Section I Village Directory i. List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at census 2011 56 ii. Alphabetical list of villages along with location code 2001 and 2011 57 iii. RD Block Wise Village Directory in prescribed format 59 Appendices to village Directory 78 Appendix-I: Summary showing total number of villages having Educational, Medical and other amenities-RD Block level Appendix-IA: Villages by number of Primary Schools Appendix-IB: Villages by Primary, Middle and Secondary Schools Appendix-IC: Villages with different sources of drinking water facilities available Appendix-II: Villages with 5,000 and above population which do not have one or more amenities available Appendix-III: Land utilisation data in respect of Census Towns Appendix-IV: RD Block wise list of inhabited villages where no amenity other than drinking water facility is available Appendix-V: Summary -

Bamboo Resource Mapping of Six Districts of Nagaland

NESAC-SR-77-2010 BAMBOO RESOURCE MAPPING FOR SIX DISTRICTS OF NAGALAND USING REMOTE SENSING AND GIS Project Report Sponsored by Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Mokokchung, Nagaland Prepared by NORTH EASTERN SPACE APPLICATIONS CENTRE Department of Space, Govt. of India Umiam – 793103, Meghalaya March 2010 NESAC-SR-77-2010 BAMBOO RESOURCE MAPPING FOR SIX DISTRICTS OF NAGALAND USING REMOTE SENSING AND GIS Project Team Project Scientist Ms. K Chakraborty, Scientist, NESAC Smt R Bharali Gogoi, Scientist, NESAC Sri R Pebam, Scientist, NESAC Principal Investigator Dr. K K Sarma, Scientist, NESAC Approved by Dr P P Nageswara Rao, Director, NESAC Sponsored by Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Mokokchung, Nagaland NORTH EASTERN SPACE APPLICATIONS CENTRE Department of Space, Govt. of India Umiam – 793103, Meghalaya March 2010 Acknowledgement The project team is grateful to Sri Rajeev M. K., Dy. General Manager (Engg.) and the Dy. Manager (Forestry), Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Nagaland, for giving us opportunity to conduct the study as well as all the support during the work. Thanks are due to Mr. A. Roy, FDP and Mr. T. Zamir, Supervisor, Forest. Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Nagaland for their support and cooperation during the field work. The team is also thankful to Dr. P P Nageswara Rao, Director, NESAC for his suggestions and encouragements. The project team thanks all the colleagues of NESAC and staff of Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Nagaland, for their help and cooperation in completion of the work. Last but not least, the funding support extended by Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Nagaland, for the work is thankfully acknowledged. -

Naga Community in Nagaland: a Historiography

Suraj Punj Journal For Multidisciplinary Research ISSN NO: 2394-2886 THE SOCIO-CULTURAL ASPECT OF FOLKLORE AND FOLKTALES AMONG AO- NAGA COMMUNITY IN NAGALAND: A HISTORIOGRAPHY Yimsusangla Longkumer, MA Final Year Reg. No 11719105, Department of history, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Jalandhar, Punjab Abstract: There is a long history of folklore and folktales in the human civilization. Through the course of modernization and westernization people usually tend to forget the great tales and stories of one’s own past. But in the late 20th century scholars have now shifted their interest in their culture and social history for the attainment of knowledge and how one own society was depicted by the great men. This research deals with the socio-cultural aspect of folklore and folktales among the Ao-Naga community. It explores the evolution its impact and cultural sustenance among them. Firstly, this article talks about the life and structure of Naga society, its focus on the literacy, education and population. Main focus on this research is to have an overall outlook of Nagaland as a whole but particularly the Ao-Naga community. Secondly, the lore's, tales and the concept of exchanging their knowledge is the main aim of this research. This article dwells with variety of tales, myths of ancestral stories that were passed on among the people with its acceptance of understanding and how it plays an important role in their lives in new time and space. Key words: Folklore, folktales, society, community. Volume 9, Issue 5, 2019 Page No: 70 Suraj Punj Journal For Multidisciplinary Research ISSN NO: 2394-2886 Introduction: Over the decades Naga’s folklore and folktales has become an important source to gain knowledge about their culture and society. -

Provisional Population Totals, Series-13, Nagaland

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 Sl!RIES--13 NAGALAND Paper-I PI~OVISIONAL POI>ULATION TO"I'ALS DANIEL KENT of the Indian Frontier Administrative Service DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, NAGALAND, 1971 CONTENTS PAGE 1. Preface V 2. Figures at a glance VI 3. Introductory Note 1 4. Statement showing a comparative picture of the population of State/Union territories of India 2-3 5. Charts & Maps: (i) Pie-chart showing the comparative Population size of the Districts, Nagaland 7 (ii) Map of Nagaland showing Decennial Population Growth Rates 1961-71 9 (iii) Explanatory note to the map of Nagaland showing Decennial Population Growth Rates 1961-71 11 (iv) Explanatory note to the map of Nagaland showing Density of Population 12 (v) Map of Nagaland showing Density of Population 13 6. Provisoinal Population Tables & Analysis of Figures: (i) TABLE-I Distribution of Population, Sex Ratio, Growth Rates and Density of Population by Districts 16-17 (ii) TABLE-II Decadal Variation in Population since 1901 18 (iii) TABLE-III Rural and Urban composition of Population 19 (iv) TABLE-IV Population of Towns 21 (v) TABLE-V Literacy 22-23 (vi) TABLE-VI Distribution of Population by Workers and Non-Workers 4 (vii) TABLE-VII DistributioB of Working Population by Agricultural & Other Workers 25 PREFACE-- AT A GLANCE as pre<:ented in this P<.Iper-I are some ofth:! basic par.ticulars.of the population of 1\l;:'tg3hnd, the 16th Stat\! of the Indian Union. The figures are still crude -and p~ovisional having "J:lo'('n compiled basing on counts from the records mad::- av'~ bIe by teams of Census workers \,.'llg'ged during the entire operation. -

Traditional Practice of Sustainable Utilisation of Forest Resources Among the Ao-Naga Tribe of Nagaland

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 7, Ver. III (July 2015), PP 01-06 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Traditional Practice of Sustainable Utilisation of Forest Resources among the Ao-Naga Tribe of Nagaland Hormila. G. Zingkhai (Research Scholar, Department of Sociology, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India) Abstract: The present paper focuses on the significance of forest and its resources in the socio-economic life of the Ao-Naga tribe of Nagaland, their traditional knowledge and practices which have aided them in sustainably utilising the forest resources and have thus helped them in conserving the forest. Like most of the other tribal communities, the Ao-Nagas also have an inextricable link with their forest and considers it as one of the most valuable resource as it provides them with all their necessities starting from food, timber, firewood, raw materials for their arts and crafts, fodder for their cattle as well as shelter. Their dependence on the forest and its resources is such that they regard it as the provider, guide, healer and protector and have found ends and means to utilise the resources efficiently. This gave rise to a well structured ecological knowledge and usage that is very much linked to an engaging day- to-day experience and survival needs, thereby, ensuing in a sustainable use and management of the forest and its resources. Keywords: Ao-Naga, Forest Resources, Sustainable Utilisation, Traditional Practice. I. Introduction Forest and its resources form an essential part of the tribal people‟s subsistence strategy as it provides them with a variety of products such as food, medicine, firewood, timber, fodder and materials for all sorts of necessities and they hunt as well as fish in the forest to supplement their needs and earn their livelihood. -

Naga Booklet-E

NAGA A PEOPLE STRUGGLING FOR SELF-DETERMINATION BY SHIMREICHON LUITHUI NAGA ince more than 50 years, an indigenous people Sliving in the mountainous Northeastern corner of the Indian Subcontinent has fought a silent war. Silent because this war has been largely ignored by the world . Ever since the Nagas have been in contact with outside powers they have fiercely resisted any attempt of subjugation. The British colonizers managed to control only parts of the rugged Naga territory, and their administration in many of these areas was only nominal. But the Naga’s struggle for self-determination is still continuing. Divided by the international boundary, they are forced to oppose both the Indian and the Burmese domination. 2 CHINA Nagaland — Nagalim The Nagas occupy a mountainous country of about NEPAL BHUTAN 100,000 square kilometers in the Patkai Range between India and Burma. About two thirds of the INDIA Naga territory is in present day India, divided among the four states Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur BANGLADESH Sydasien and Nagaland. The rest lies in Sagiang and Thangdut states in Burma. It is believed that the ancestors of INDIA MYANMAR today’s Nagas migrated to the Patkai Range from an (Burma) unknown area in Southwestern China thousands of Bay of Bengal years ago. When Nagas refer to Nagaland they mean the entire area inhabited by Nagas which have been partitioned by the British between India and Burma. The Indian Union created a State in 1963, named Nagaland Stereotypes about the Nagas comprising of only one third of the land inhabited by Nagas. Since 1997 Nagas have started using the The stereotype of the Nagas as a fierce people, word „Nagalim“ in place of „Nagaland“.