Communicating Jesus: the Encoding and Decoding Practices of Re-Presenting Jesus for LDS (Mormon) Audiences at a BYU Art Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wise Or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 57 Issue 2 Article 4 2018 Wise or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art Jennifer Champoux Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Champoux, Jennifer (2018) "Wise or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 57 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol57/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Champoux: Wise or Foolish Wise or Foolish Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art Jennifer Champoux isual imagery is an inescapable element of religion. Even those Vgroups that generally avoid figural imagery, such as those in Juda- ism and Islam, have visual objects with religious significance.1 In fact, as David Morgan, professor of religious studies and art history at Duke University, has argued, it is often the religions that avoid figurative imag- ery that end up with the richest material culture.2 To some extent, this is true for Mormonism. Although Mormons believe art can beautify a space, visual art is not tied to actual ritual practice. Chapels, for exam- ple, where the sacrament ordinance is performed, are built with plain walls and simple lines and typically have no paintings or sculptures. Yet, outside chapels, Mormons enjoy a vast culture of art, which includes traditional visual arts, texts, music, finely constructed temples, clothing, historical sites, and even personal devotional objects. -

Mormon Abstract

Abstract http://www.mormonartistsgroup.com/Mormon_Artists_Group/Abstract.html Welcome What's New Works Glimpses Events Freebies About MAG Contact Mormon Abstract by Stephanie K. Northrup January 2010 [i] When you think of Mormons “pushing the envelope,” what comes to mind? Deacons at the door collecting fast offerings? Try Bethanne Andersen’s The Last Supper (Place Setting). Many beautiful renditions of the Last Supper already exist, telling the story through dramatic lighting, facial expressions, and body language. Andersen tries a new perspective. She paints the dishes from which Christ eats His last mortal meal. That’s it. No people. Just us – invited to put ourselves in His shoes. The dishes are painted in soft pastel, as if on the verge of fading. This is a fleeting moment, like mortality, as He sits with His friends before making the ultimate sacrifice. By pushing the envelope, by throwing a new image at us that makes us consider the story in a new way, Andersen invites viewer participation. What a great approach to “likening the scriptures.” While Greg Olsen, Del Parson, and Simon Dewey are household names, ask most Mormons to name an abstract artist in the Church and you’ll probably get blank stares. Do Mormons make abstract art? We do. And we have been for a long time. In 1890, the church sent John Hafen and other “art missionaries” to Paris. Their assignment was to improve their skill so that they could create art for the Salt Lake Temple. What did these artists return with? Impressionism! Bright, thick brush strokes replaced traditional refined detail. -

The Role of Art in Teaching LDS History and Doctrine

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 16 Number 3 Article 5 10-2015 The Role of Art in Teaching LDS History and Doctrine Anthony Sweat Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sweat, Anthony. "The Role of Art in Teaching LDS History and Doctrine." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 16, no. 3 (2015): 40-57. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol16/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Role of Art in Teaching Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine anthony sweat Anthony Sweat ([email protected]) is an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU. This article is an expanded and adapted version from an appendix in the book From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publication of the Book of Mormon, by Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat. How far has Fine Art, in all or any ages of the world, been conducive to the reli- gious life? —John Ruskin, Modern Painters, 1856 1 . © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. © Intellectual Reserve, eing a Brigham Young University religion professor and a part-time pro- Bfessionally trained artist2 is a bit like being a full-time police officer and a weekend race-car driver. At times the two labors are mutually reinforcing, and at others they are completely at odds. -

SEPTEMBER 2003 Liahona

ÅRGÅNG 127 • NUMMER 9 • JESU KRISTI KYRKA AV SISTA DAGARS HELIGA • SEPTEMBER 2003 Liahona Ett bättre förbund, s 2 Ungdomar skapar musik i Manitoba i Canada, s 18 ÅRGÅNG 127 • NUMMER 9 • JESU KRISTI KYRKA AV SISTA DAGARS HELIGA • SEPTEMBER 2003 Liahona ARTIKLAR 2 Budskap från första presidentskapet: Ett bättre förbund James E Faust 10 Undervisa med tro Robert D Hales 25 Besökslärarnas budskap: Förbered dig för att få personlig uppenbarelse 30 Hitta farfar Pablo Raquel Pedraza de Brosio PÅ OMSLAGET Framsidan: Kristus och den 32 Jesu liknelser: Arbetarna Henry F Acebedo samaritiska kvinnan, av Carl Heinrich Bloch, med 36 De forntida apostlarnas ord: Principer för att bygga upp kyrkan tillstånd av Nationalhistoriska Richard J Maynes Muséet vid Frederiksborg i Hillerød, Danmark. Baksidan: 40 Sista dagars heliga berättar Kristus gav oss liknelsen om Min fars tapperhetsmedalj Emmanuel Fleckinger den barmhärtige samariten, Min dotters bön Kari Ann Rasmussen av Robert T Barrett. Finn frid genom förlåtelse Anonym författare En kompass i tjock dimma Lin Tsung-Ting 44 För dessa mina minsta Víctor Guillermo Chauca Rivera 48 Så kan du använda Liahona september 2003 UNGDOMSSIDORNA 7Affisch: Var en stark länk 8 Jag hittade en skatt D Rex Gerratt LILLA STJÄRNAN OMSLAGET 18 Not för not för not Shanna Ghaznavi Illustration Mark W Robison. 22 Med kärlek Stefania Postiglione 24 Råd och förslag: Roliga veckoträffar 26 Håller inte måttet Chad Morris 47 Visste du det här? LILLA STJÄRNAN 2Kom, lyssna till profetens röst: Spår i snön Thomas S Monson 4 Samlingsstunden: -

[email protected] 299 South Main Street, Suite #1375 Salt Lake City, Utah 84111 Phone: 1.888.234.3706

Case 2:19-cv-00554-RJS-DBP Document 85-1 Filed 03/17/21 PageID.1094 Page 1 of 135 Kay Burningham (#4201) [email protected] 299 South Main Street, Suite #1375 Salt Lake City, Utah 84111 Phone: 1.888.234.3706 Attorney for Plaintiff and for the Class UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH LAURA A. GADDY, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, [PROPOSED] SECOND AMENDED CLASS Plaintiffs, ACTION COMPLAINT v. (DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL) CORPORATION of THE PRESIDENT OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST Case Number: 2:19-cv-00554-RJS-DBP OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS, a Utah corporation sole. Presiding Judge: Robert J. Shelby Defendant. Magistrate Judge: Dustin B. Pead I. NATURE OF THE CASE 1. Plaintiff LAURA GADDY (“LAURA”) brings this case on behalf of hundreds of thousands of Mormons who have resigned from the Mormon aka “LDS” Church, against [the] Corporation of the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (“COP”). The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints™ (“COJCOLDS”), is a COP-owned a trademark.1 1 Despite the 2011-2013 “I’m a Mormon” ad campaign, in 2019 LDS President Russell L. Nelson announced it was no longer acceptable to refer to the Church as “Mormon,” its members as Mormons or LDS; the preferred term is now the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Since then, COP has changed its official domain and other identifiers to comply with Nelson’s mandate. For brevity, this complaint will ordinarily use “LDS,” but will use “Mormon” and/or “Mormonism,” when referencing 19th Century Mormon historical events. -

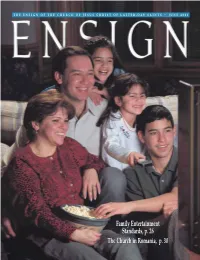

June 2001 Ensign

THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JUNE 2001 FamilyFamily EntertainmentEntertainment Standards,Standards, p.p. 2626 TheThe ChurchChurch inin Romania,Romania, p.p. 3030 Beautiful Nauvoo, by Larry C. Winborg “The name of our city (Nauvoo) is of Hebrew origin, and signifies a beautiful situation, or place, carrying with it, also, the idea of rest; and is truly descriptive of the most delightful location” (“A Proclamation of the First Presidency of the Church to the Saints Scattered Abroad,” 15 Jan. 1841, History of the Church, 4:268). THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JUNE 2001 VOLUME 31 NUMBER 6 2 “BEHOLD YOUR LITTLE ONES” ON THE COVERS: Front: Photo by Steve Bunderson. Back: President Gordon B. Hinckley Photo by Craig Dimond. Inside front: Beautiful Nauvoo, by Larry C. Winborg, oil on canvas, 36” x 48”, 1998. 6MIRACLES Elder Dallin H. Oaks Courtesy of Brynn and Steve Burrows. Inside back: Joseph 18 JUSTIFICATION AND SANCTIFICATION Smith, American Prophet, by Del Parson, oil on canvas, 30” x 24”, 1998. Used by permission of Deseret Book Company. Elder D. Todd Christofferson THE FIRST PRESIDENCY: Gordon B. Hinckley, 26 SETTING FAMILY STANDARDS Thomas S. Monson, James E. Faust FOR ENTERTAINMENT Carla Dalton QUORUM OF THE TWELVE: Boyd K. Packer, L. Tom Perry, David B. Haight, Neal A. Maxwell, Russell M. Nelson, Dallin H. Oaks, 30 THE CHURCH IN ROMANIA M. Russell Ballard, Joseph B. Wirthlin, Richard G. Scott, Robert D. Hales, Jeffrey R. Holland, Henry B. Eyring LaRene Porter Gaunt NSWERS LL ROUND E EDITOR: Dennis B. -

Setting a Standard in LDS Art: Four Illustrators of the Mid- Twentieth Century

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 3 4-1-2005 Setting a Standard in LDS Art: Four Illustrators of the Mid- Twentieth Century Robert T. Barrett Susan Easton Black Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Barrett, Robert T. and Black, Susan Easton (2005) "Setting a Standard in LDS Art: Four Illustrators of the Mid-Twentieth Century," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 44 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Barrett and Black: Setting a Standard in LDS Art: Four Illustrators of the Mid-Twent Harry Anderson, The Second Coming. Although Church members will likely recognize this painting and other works of art discussed in this article, they may not be familiar with the artists who created them. Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2005 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 44, Iss. 2 [2005], Art. 3 Setting a Standard in LDS Art Four Illustrators of the Mid-Twentieth Century Robert T. Barrett and Susan Easton Black rints of paintings of Christ and other people from the scriptures and PChurch history are displayed in Latter-day Saint meetinghouses, visi tors' centers, and temples throughout the world and are used in Church magazines and manuals. Many of these artworks were created in the 1950s and 1960s by American illustrators Arnold Friberg, Harry Anderson, Tom Lovell, and Ken Riley. -

Mormon Experience Scholarship Issues & Art

MORMON EXPERIENCE SCHOLARSHIP ISSUES & ART SEEING JOSEPH SUNSTONESUNSTONE SMITH: THE CHANGING IMAGE OF THE MORMON PROPHET by Robert A. Rees (p.18) TRACKING THE SINCERE BELIEVER Laurie F. Maffly- Kipp examines the obsession with Joseph Smith’s sincerity (p.28) JOSEPH SMITH REVISED AND ENLARGED by Hugo Olaiz (p.70) H. Parker Blount reflects on LDS environmental rhetoric and practices (p.42) A LEAF, A BOWL, AND A PIECE OF JADE, Brown fiction contest winner by Joy Robinson (p.48) UPDATE President Hinckley undergoes surgery; Utah’s “Origins of life” debate; film controversies; and more! (p.74) December 2005—$5.95 UPCOMING SUNSTONE SYMPOSIUMS MAKE PLANS TO ATTEND! MARCH APRIL 18 21-22 SUNSTONE SUNSTONE SOUTHWEST dallas WEST claremont, california 2006 SALT LAKE SUNSTONE SYMPOSIUM CALL FOR PAPERS FORMATS SUBMITTING PROPOSALS DEADLINE Sessions may be scholarly Those interested in being a part In order to receive first-round papers, panel discussions, of the program this year should consideration, PROPOSALS interviews, personal essays, submit a proposal which includes SHOULD BE RECEIVED BY sermons, dramatic performances, a session title, 100-word abstract, 1 MAY 2006. Sessions will be literary readings, debates, comic a separate summary of the topic’s accepted according to standards routines, short films, art displays, relevance and importance to of excellence in scholarship, or musical presentations. We Mormon studies, and the name thought, and expression. All encourage proposals on the and a brief vita for all proposed subjects, ideas, and persons to symposium theme, but as always, presenters. be discussed must be treated with we welcome reflections on any respect and intelligent discourse; topic that intersects with Mormon proposals with a sarcastic or experience. -

Why Does Latter-Day Saint Art Matter? with Jennifer Champoux Released May 8

Latter-day Saint Perspectives Podcast Episode 106: Why Does Latter-day Saint Art Matter? with Jennifer Champoux Released May 8, 2019 This is not a verbatim transcript. Some wording has been modified for clarity. Laura Harris Hales: Hello, this is Laura Harris Hales. I’m here today with Jenny Champoux, who has an interesting background. You have a master’s in art history, but that’s not what you started out studying. Do you want to tell us a little bit about your background? Jennifer Champoux: Sure. Thank you. When I was at Brigham Young University, I got my undergraduate degree in international politics and political science, and I did a minor in art history. I went on an art history study abroad to Europe and then ended up writing an honors thesis paper on a Flemish artist and just fell in love with the research and writing process in art history. I realized that that was really what I love to do. I decided to pursue a master’s degree in art history, and I took some extra art history classes, learned French, and did my graduate work at Boston University studying Dutch art of the Golden Age, Baroque art. Laura Harris Hales: You lecture part-time on art history right now, don’t you? Jennifer Champoux: I do. I’m adjunct faculty at Northeastern University. Laura Harris Hales: Our discussion today is based on your article “Wise or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art,” published in the summer 2018 issue of BYU Studies Quarterly, which is a tough venue. -

Teachings of Presidents of the Church Harold B. L Ee Teachings of Presidents of the Church Harold B

TEACHINGS OF PRESIDENTS OF THE CHURCH HAROLD B. L EE TEACHINGS OF PRESIDENTS OF THE CHURCH HAROLD B. LEE Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Your comments and suggestions about this book would be appreciated. Please submit them to Curriculum Planning, 50 East North Temple Street, Floor 24, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-3200 USA. E-mail: [email protected] Please list your name, address, ward, and stake. Be sure to give the title of the book. Then offer your comments and suggestions about the book’s strengths and areas of potential improvement. © 2000 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 5/00 Contents Title Page Introduction . v Historical Summary . viii The Ministry of Harold B. Lee . xi 1 The Way to Eternal Life . 1 2 Who Am I? . 9 3 The Lamb Slain from the Foundation of the World . 18 4 The First Principles and Ordinances of the Gospel . 27 5 Walking in the Light of Testimony . 37 6 To Hear the Voice of the Lord . 47 7 The Scriptures, “Great Reservoirs of Spiritual Water” . 59 8 Joseph Smith, Prophet of the Living God . 69 9 Heeding the True Messenger of Jesus Christ . 79 10 Loving, Faithful Priesthood Service . 89 11 Priceless Riches of the Holy Temple . 99 12 The Divine Purpose of Marriage . .109 13 Teaching the Gospel in the Home . .119 14 Love at Home . .129 15 The Righteous Influence of Mothers . .138 16 Uniting to Save Souls . -

An Urban Mormon Country by Rebecca

Between Mountain and Lake: An Urban Mormon Country by Rebecca Andersen A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved November 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Susan Gray, Chair Susan Rugh Stephen Pyne ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2015 ABSTRACT In "Between Mountain and Lake: an Urban Mormon Country," I identify a uniquely Mormon urban tradition that transcends simple village agrarianism. This tradition encompasses the distinctive ways in which Mormons have thought about cities, appropriating popular American urban forms to articulate their faith's central beliefs, tenants, and practices, from street layout to home decorating. But if an urban Mormon experience has as much validity as an agrarian one, how have the two traditions articulated themselves over time? What did the city mean for nineteenth-century Mormons? Did these meanings change in the twentieth-century, particularly following World War II when the nation as a whole underwent rapid suburbanization? How did Mormon understandings of the environment effect the placement of their villages and cities? What consequences did these choices have for their children, particularly when these places rapidly suburbanized? Traditionally, Zion has been linked to a particular place. This localized dimension to an otherwise spiritual and utopian ideal introduces environmental negotiation and resource utilization. Mormon urban space is, as French thinker Henri Lefebvre would suggest, culturally constructed, appropriated and consumed. On a fundamental level, Mormon spaces tack between the extremes of theocracy and secularism, communalism and capitalism and have much to reveal about how Mormonism has defined gender roles and established racial hierarchies. -

December 2002 Ensign

THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • DECEMBER 2002 Christmas on Temple Square, p. 34 Hope in Christ, p. 6 The Birth of Jesus, by Del Parson “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6). DECEMBER 2002 • VOLUME 32, NUMBER 12 2 FIRST PRESIDENCY MESSAGE A Testimony of the Son of God President Gordon B. Hinckley 6Finding Hope in Christ Elder Johann A. Wondra 10 A Cloud of Witnesses Stephen K. Iba 14 More Than Lights and Bright Colors Patricia Merlos Finding Hope 16 GOSPEL CLASSICS 6 in Christ The Gifts of Christmas President Howard W. Hunter 20 The Power of Compassion Neil K. and Lloyd D. Newell 26 Little Boy Lost Emmett R. Smith 29 When Children Want to Bear Testimony Elder Carl B. Cook 34 ON SITE In Light of His Birth 42 The Man in the Leather Coat Elder David B. Haight The Power 44 Wanted: Modern Nehemiahs 20 of Compassion Elder Modesto M. Amistad Jr. 47 Ezra Unfolds the Scriptures Brian D. Garner 50 QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Using careful judgment in choosing the music we listen to 52 LATTER-DAY SAINT VOICES 56 Living after the Manner of Happiness Elder Marlin K. Jensen 63 VISITING TEACHING MESSAGE Rejoice in the Blessings of the Temple 64 RANDOM SAMPLER In Light A Cloud 66 NEWS OF THE CHURCH 34 of His Birth of Witnesses 71 ANNUAL INDEX 10 THE FIRST PRESIDENCY: Gordon B.