Twenty Kr Narayanan Orations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Prof. Mrinal Datta Chaudhuri, MDC to All His Students, and Mrinal-Da to His Junior Colleagues and Friends, Was a Legendary Teacher of the Delhi School of Economics

Prof. Mrinal Dutta Chaudhuri Memorial Meeting Tuesday, 21st July, 2015 at DELHI SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS University of Delhi Delhi – 110007 1 1934-2015 2 3 PROGRAMME Prof. Pami Dua, Director, DSE - Opening Remarks (and coordination) Dr. Malay Dutta Chaudhury, Brother of Late Prof. Mrinal Dutta Chaudhuri Prof. Aditya Bhattacharjea, HOD Economics, DSE - Life Sketch Condolence Messages delivered by : Dr. Manmohan Singh, Former Prime Minister of India (read by Prof. Pami Dua) Prof. K.L.Krishna Prof. Badal Mukherji Prof. K. Sundaram Prof. Pulin B. Nayak Prof. Partha Sen Prof. T.C.A. Anant Prof. Kirit Parikh Mr. Nitin Desai Prof. J.P.S. Uberoi Prof. Pranab Bardhan Prof. Andre Beteille, Prof.Amartya Sen (read by Prof. Rohini Somanathan) Prof. Kaushik Basu, Dr. Omkar Goswami (read by Prof. Ashwini Deshpande) Prof. Abhijit Banerjee, Prof. Anjan Mukherji, Dr. Subir Gokaran (read by Prof. Aditya Bhattacharjea) Prof. Prasanta Pattanaik, Prof. Bhaskar Dutta, Prof. Dilip Mookherjee (read by Prof. Sudhir Shah) Dr. Sudipto Mundle Prof. Ranjan Ray, Prof. Vikas Chitre (read by Prof. Aditya Bhattacharjea) Prof. Adi Bhawani Mr. Paranjoy Guha Thakurta Prof. Meenakshi Thapan Prof. B.B.Bhattacharya, Prof. Maitreesh Ghatak, Prof.Gopal Kadekodi, Prof. Shashak Bhide, Prof.V.S.Minocha, Prof.Ranganath Bhardwaj, Ms. Jasleen Kaur (read by Prof. Pami Dua) 4 Prof. Pami Dua, Director, DSE We all miss Professor Mrinal Dutta Chaudhuri deeply and pay our heartfelt and sincere condolences to his family and friends. We thank Dr. Malay Dutta Chaudhuri, Mrinal’s brother for being with us today. We also thank Dr. Rajat Baishya, his close relative for gracing this occasion. -

Management Accountant

7+(0$1$*(0(17 THE MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANT ACCOUNTANT THE MANAGEMENT SEPTEMBER 2016 9 51 NO. VOL. 7+(-2851$/)25&0$V $&&2817$17 ,661 6HSWHPEHU92/123DJHV ÃÌÊ «iÌÌÛiiÃÃ ` 100 «iÝÌÞÊÌÊ v`iVi 7+(,167,787(2)&267$&&2817$1762),1',$ 6WDWXWRU\ERG\XQGHUDQ$FWRI3DUOLDPHQW ZZZLFPDLLQ www.icmai.in September 2016 The Management Accountant 1 2 The Management Accountant September 22016 www.icmai.in The Institute of Cost Accountants of India PRESIDENT THE INSTITUTE OF COST ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA CMA Manas Kumar Thakur (erstwhile The Institute of Cost and Works Accountants [email protected] of India) was first established in 1944 as a registered VICE PRESIDENT CMA Sanjay Gupta company under the Companies Act with the objects of [email protected] promoting, regulating and developing the profession of COUNCIL MEMBERS Cost Accountancy. CMA Amit Anand Apte, CMA Ashok Bhagawandas Nawal, On 28 May 1959, the Institute was established by a CMA Avijit Goswami, CMA Balwinder Singh, special Act of Parliament, namely, the Cost and Works CMA Biswarup Basu, CMA H. Padmanabhan, Accountants Act 1959 as a statutory professional body for CMA Dr. I. Ashok, CMA Niranjan Mishra, CMA Papa Rao Sunkara, CMA P. Raju Iyer, the regulation of the profession of cost and management CMA Dr. P V S Jagan Mohan Rao, accountancy. CMA P. V. Bhattad, CMA Vijender Sharma It has since been continuously contributing to the Shri Ajai Das Mehrotra, Shri K.V.R. Murthy, growth of the industrial and economic climate of the Shri Praveer Kumar, Shri Surender Kumar, country. Shri Sushil Behl The Institute of Cost Accountants of India is the only Secretary recognised statutory professional organisation and CMA Kaushik Banerjee, [email protected] licensing body in India specialising exclusively in Cost Sr. -

SSC JE 2018 General Awareness Paper

QID : 651 - Income and Expenditure Account is ___________. Options: 1) Property account 2) Personal Account 3) Nominal Account 4) Capital Account Correct Answer: Nominal Account QID : 652 - Commodity or product differentiation is found in which market? Options: 1) Perfect Competition Market 2) Monopoly Market 3) Imperfect Competition Market 4) No option is correct Correct Answer: Imperfect Competition Market QID : 653 - The economist who for the first time scientifically determined National Income in India is ___________. Options: 1) Jagdish Bhagwati 2) V.K.R.V. Rao 3) Kaushik Basu 4) Manmohan Singh Correct Answer: V.K.R.V. Rao QID : 654 - Which of the following is not a part of the non-plan expenditure of central government? Options: 1) Interest payment 2) Grants to states 3) Electrification 4) Subsidy Correct Answer: Electrification QID : 655 - The percentage of decadal growth of population of India during 2001-2011 as per census 2011 is ___________. Options: 1) 15.89 2) 17.64 3) 19.21 4) 21.54 Correct Answer: 17.64 QID : 656 - The concept of Constitution first originated in which of the following countries? Options: 1) Italy 2) China 3) Britain 4) France Correct Answer: Britain QID : 657 - The Parliament has been given power to make laws regarding citizenship under which article of the Constitution of India? Options: 1) Article 5 2) Article 7 3) Article 9 4) Article 11 Correct Answer: Article 11 QID : 658 - Which one of the following cannot be the ground for proclamation of Emergency under the Constitution of India? Options: 1) War 2) Armed rebellion 3) External aggression 4) Internal disturbance Correct Answer: Internal disturbance QID : 659 - The 100th amendment in Indian Constitution provides ___________. -

Free Trade: What Now? by Jagdish Bhagwati This Is the Text Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Free Trade: What Now? By Jagdish Bhagwati This is the text of the Keynote Address delivered at the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland, on 25th May 1998, on the occasion of the International Management Symposium at which the 1998 Freedom Prize of the Max Schmidheiny Foundation was awarded. Ever since Adam Smith invented the case for free trade over two centuries ago in The Wealth of Nations, and founded in the same great work the science of Economics as we know it today, international economists have been kept busy defending free trade. A popular children’s story in the United States, by Dr. Seuss, has the refrain “And the cat came back”. The opponents of free trade, ranging from hostile protectionists to the mere skeptics, have kept coming back with ever new objections. The critiques we have had to confront have often come from those who fail to understand the essential insight of Adam Smith: that it pays me to specialize on what I do best compared to you, even though I can do everything better than you do. Economists call this the Law of Comparative Advantage: each nation would profit from noncoercive free trade that would lead to such specialization. When asked by the famous mathematician Ulam: “What is the most counterintuitive result in Economics?”, the Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson chose this Law as his candidate.1 Skeptics within Economics But the most compelling skeptics have come repeatedly from within the discipline of Economics itself. -

HLA MYINT 105 Neoclassical Development Analysis: Its Strengths and Limitations 107 Comment Sir Alec Cairn Cross 137 Comment Gustav Ranis 144

Public Disclosure Authorized pi9neers In Devero ment Public Disclosure Authorized Second Theodore W. Schultz Gottfried Haberler HlaMyint Arnold C. Harberger Ceiso Furtado Public Disclosure Authorized Gerald M. Meier, editor PUBLISHED FOR THE WORLD BANK OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Public Disclosure Authorized Oxford University Press NEW YORK OXFORD LONDON GLASGOW TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON HONG KONG TOKYO KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE JAKARTA DELHI BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI NAIROBI DAR ES SALAAM CAPE TOWN © 1987 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Manufactured in the United States of America. First printing January 1987 The World Bank does not accept responsibility for the views expressed herein, which are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank or to its affiliated organizations. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pioneers in development. Second series. Includes index. 1. Economic development. I. Schultz, Theodore William, 1902 II. Meier, Gerald M. HD74.P56 1987 338.9 86-23511 ISBN 0-19-520542-1 Contents Preface vii Introduction On Getting Policies Right Gerald M. Meier 3 Pioneers THEODORE W. SCHULTZ 15 Tensions between Economics and Politics in Dealing with Agriculture 17 Comment Nurul Islam 39 GOTTFRIED HABERLER 49 Liberal and Illiberal Development Policy 51 Comment Max Corden 84 Comment Ronald Findlay 92 HLA MYINT 105 Neoclassical Development Analysis: Its Strengths and Limitations 107 Comment Sir Alec Cairn cross 137 Comment Gustav Ranis 144 ARNOLD C. -

Magazine Can Be Printed in Whole Or Part Without the Written Permission of the Publisher

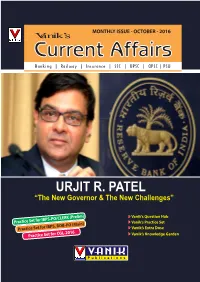

MONTHLY ISSUE - OCTOBER - 2016 CurrVanik’s ent Affairs Banking | Railway | Insurance | SSC | UPSC | OPSC | PSU URJIT R. PATEL “The New Governor & The New Challenges” Vanik’s Question Hub -PO/CLERK (Prelim) Practice Set for IBPS Vanik’s Practice Set -PO (Main) Practice Set for IBPS, BOB Vanik’s Extra Dose GL-2016 Practice Set for C Vanik’s Knowledge Garden P u b l i c a t i o n s VANIK'S PAGE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORTS OF INDIA NAME OF THE AIRPORT CITY STATE Rajiv Gandhi International Airport Hyderabad Telangana Sri Guru Ram Dass Jee International Airport Amristar Punjab Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport Guwaha ti Assam Biju Patnaik International Airport Bhubaneshwar Odisha Gaya Airport Gaya Bihar Indira Gandhi International Airport New Delhi Delhi Andaman and Nicobar Veer Savarkar International Airport Port Blair Islands Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport Ahmedabad Gujarat Kempegowda International Airport Bengaluru Karnatak a Mangalore Airport Mangalore Karnatak a Cochin International Airport Kochi Kerala Calicut International Airport Kozhikode Kerala Trivandrum International Airport Thiruvananthapuram Kerala Raja Bhoj Airport Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Devi Ahilyabai Holkar Airport Indore Madhya Pradesh Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport Mumbai Maharashtr a Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport Nagpur Maharashtr a Pune Airport Pune Maharashtra Zaruki International Airport Shillong Meghalay a Jaipur International Airport Jaipur Rajasthan Chennai International Airport Chennai Tamil Nadu Civil Aerodrome Coimbator e Tamil Nadu Tiruchirapalli International Airport Tiruchirappalli Tamil Nadu Chaudhary Charan Singh Airport Lucknow Uttar Pradesh Lal Bahadur Shastri International Airport Varanasi Uttar Pradesh Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose International Airport Kolkata West Bengal Message from Director Vanik Publications EDITOR Dear Students, Mr. -

Annual Report 2015-2016 Research Themes

Annual Report 2015-2016 Research Themes The research themes of the initiative are explored through public lectures, seminars, conferences, films, research projects, and outreach.� The Initiative currently conducts research on the following themes: 1 Indian Urbanization: Governance, Politics and Political Economy 2 Economic Inequalities and Change 3 Pluralism and Diversities 4 Democracy Above: Engaged audience at Student Fellowship Presentation Front Cover: Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus at Sunset. Mumbai, India. Image: Paul Prescot 1 OP Jindal Distinguished Lecture Series To promote a serious discussion of politics, economics, social and cultural change in modern India, Sajjan and Sangita Jindal have endowed, in perpetuity, the OP Jindal Distinguished Lectures by major scholars and public figures.� Fall 2015 MONTEK SINGH AHLUWALIA and also in books. He co-authored Re-distribution In October 2015, Montek Singh Ahluwalia with Growth: An Approach to Policy (1975). He delivered the OP Jindal Distinguished Lectures. also wrote, “Reforming the Global Financial Ahluwalia has served as a high-level government Architecture”, which was published in 2004 as official in India, as well as with the IMF and the Economic paper No.41 by the Commonwealth World Bank. He has been a key figure in India’s Secretariat, London. Ahluwalia is an honorary economic reforms since the mid-1980s. Most fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford and a member recently, Ahluwalia was Deputy Chairman of the of the Governing Council of the Global Green Planning Commission from July 2004 till May Growth Institute, a new international organization 2014. In addition to this Cabinet level position, based in South Korea. He is a member of the Ahluwalia was a Special Invitee to the Cabinet Alpbach-Laxenburg Group established by the and several Cabinet Committees. -

Rohini Pande

ROHINI PANDE 27 Hillhouse Avenue 203.432.3637(w) PO Box 208269 [email protected] New Haven, CT 06520-8269 https://campuspress.yale.edu/rpande EDUCATION 1999 Ph.D., Economics, London School of Economics 1995 M.Sc. in Economics, London School of Economics (Distinction) 1994 MA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, Oxford University 1992 BA (Hons.) in Economics, St. Stephens College, Delhi University PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2019 – Henry J. Heinz II Professor of Economics, Yale University 2018 – 2019 Rafik Hariri Professor of International Political Economy, Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University 2006 – 2017 Mohammed Kamal Professor of Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University 2005 – 2006 Associate Professor of Economics, Yale University 2003 – 2005 Assistant Professor of Economics, Yale University 1999 – 2003 Assistant Professor of Economics, Columbia University VISITING POSITIONS April 2018 Ta-Chung Liu Distinguished Visitor at Becker Friedman Institute, UChicago Spring 2017 Visiting Professor of Economics, University of Pompeu Fabra and Stanford Fall 2010 Visiting Professor of Economics, London School of Economics Spring 2006 Visiting Associate Professor of Economics, University of California, Berkeley Fall 2005 Visiting Associate Professor of Economics, Columbia University 2002 – 2003 Visiting Assistant Professor of Economics, MIT CURRENT PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES AND SERVICES 2019 – Director, Economic Growth Center Yale University 2019 – Co-editor, American Economic Review: Insights 2014 – IZA -

Annual Report 2016-17

Annual Report 2016-17 National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi 41st ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC FINANCE AND POLICY NEW DELHI Annual Report April 1st, 2016 – March 31st, 2017 Printed and Published by the Secretary, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (An autonomous research Institute under the Ministry of Finance, Government of India) 18/2, Satsang Vihar Marg, Special Institutional Area (Near JNU), New Delhi 110067 Tel. No.: 011 26569303, 26569780, 26569784 Fax: 91-11-26852548 email: [email protected] website: www.nipfp.org.in Edited & Designed by Samreen Badr Printed by: VAP email: [email protected] Tel: 09811285510 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Research Activities 5 2.1 Taxation and Revenue 2.2 Public Expenditure and Fiscal Management 2.3 Macroeconomic Aspects 2.4 Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations 2.5 State Planning and Development 2.6 New projects initiated 3. Workshops, Seminars, Meetings and Conferences 15 4. Training Programmes 17 5. Publications and Communications 19 6. Library and Information Centre 21 7. Highlights of Faculty Activities 25 Annexures I. List of Studies 2016-2017 51 II. NIPFP Working Paper Series 56 III. Internal Seminar Series 58 I V. List of Governing Body Members as on 31.03.2017 60 V. List of Priced Publications 64 VI. Published Material of NIPFP Faculty 68 VII. List of Staff Members as on 31.03.2017 74 VIII. List of Sponsoring, Corporate, Permanent, and Ordinary Members as on 31.03.2017 78 IX. Finance and Accounts 79 1. INTRODUCTION e 41st Annual Report of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi is a reection of the Insti- tute’s work in the nancial year and accountability to the Governing Body and to the public. -

Report on India Banking Conclave

About Us Centre for Economic Policy Research, or CEPR is an in- dependent think tank, which works in macro-economy, politico-economy, public-policy, banking, agriculture, in- frastructure, energy, international trade, manufacturing sectors. CEPR helps government in shaping the policy, via sector reports, stakeholder consultations, policy briefs et al. Along with this, CEPR also helps the organ- isations to understand the public policy and the market scenarios. CEPR fills up gab between the industry and policymakers and strives to make both ends meet. Nationally, CEPR is network of nearly 50 odd profession- als and economists, who are regularly contributing to make the work more meaningful. At present we operate out of two offices, Noida in Delhi NCR and Chandigarh. Centre for Economic Policy Research Plot No. 658, Phase -1, Industrial Area, Chandigarh-160002 201, Vikram Tower, Grihaparvesh, Sector-77, Noida- 201304 Tel : 0120 - 4165609 [email protected] @ceprindia cepr.in IBC Conference Report 23-24 August 2018, ITC Maurya, New Delhi 3 INDIA BANKING CONCLAVE 2018 The noise around NPAs is because of the previous government. Banks were pressurised to give loans to big businessmen; this scam was bigger than commonwealth, 2G or coal scam. The NDA government is taking steps to secure the banks and depositors.” Narendra Modi Prime Minister of India 4 INDIA BANKING CONCLAVE 2018 CONTENT The Future of Indian Banks 8 Objective 13 Session List 14 Day 1 Inaugural Session 16 Session 1: Indian Debt, Indian Problem, Indian Solution 20 Session 2: India and Development Banks 24 Session 3: FinTech for New-India 26 In Conversation: India, Plan 2030 & Banks 28 Day 2 Session 1: Small is Good- Funding The Unfunded 30 Session 2: Biting the Bullet Privatisation Vs Mergers 34 Session 3: New Dawn: Banks of Tomorrow 36 A Master Class with Union Minister Piyush Goyal 38 Valedictory Session: Banks for Rebuilding India 39 6 TEAM Gopal Krishna Agarwal National Spokesperson (Economic Affairs), BJP Independent Director, Bank of Baroda Chief Advisor, India Banking Conclave Dr. -

Annual Report 1 Start

21st Annual Report MADRAS SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Chennai 01. Introduction ……. 01 02. Review of Major Developments ……. 02 03. Research Projects ……. 05 04. Workshops / Training Programmes …….. 08 05. Publications …….. 09 06. Invited Lectures / Seminars …….. 18 07. Cultural Events, Student Activities, Infrastructure Development …….. 20 08. Academic Activities 2012-13 …….. 24 09. Annexures ……... 56 10. Accounts 2012 – 13 ……… 74 MADRAS SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Chennai Introduction TWENTY FIRST ANNUAL REPORT 2013-2014 1. INTRODUCTION With able guidance and leadership of our Chairman Dr. C. Rangarajan and other Board of Governors of Madras School of Economics (MSE), MSE completes its 21 years as on September 23, 2014. During these 21 years, MSE reached many mile stones and emerged as a leading centre of higher learning in Economics. It is the only center in the country offering five specialized Masters Courses in Economics namely M.Sc. General Economics, M.Sc. Financial Economics, M.Sc. Applied Quantitative Finance, M.Sc. Environmental Economics and M.Sc. Actuarial Economics. It also offers a 5 year Integrated M.Sc. Programme in Economics in collaboration with Central University of Tamil Nadu (CUTN). It has been affiliated with University of Madras and Central University of Tamil Nadu for Ph.D. programme. So far twelve Ph.Ds. and 640 M.Sc. students have been awarded. Currently six students are pursuing Ph.D. degree. The core areas of research of MSE are: Macro Econometric Modeling, Public Finance, Trade and Environment, Corporate Finance, Development, Insurance and Industrial Economics. MSE has been conducting research projects sponsored by leading national and international agencies. It has successfully completed more than 110 projects and currently undertakes more than 20 projects.