Trends and Issues in Tax Policy and Reform in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Annual Report 1 Start

21st Annual Report MADRAS SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Chennai 01. Introduction ……. 01 02. Review of Major Developments ……. 02 03. Research Projects ……. 05 04. Workshops / Training Programmes …….. 08 05. Publications …….. 09 06. Invited Lectures / Seminars …….. 18 07. Cultural Events, Student Activities, Infrastructure Development …….. 20 08. Academic Activities 2012-13 …….. 24 09. Annexures ……... 56 10. Accounts 2012 – 13 ……… 74 MADRAS SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Chennai Introduction TWENTY FIRST ANNUAL REPORT 2013-2014 1. INTRODUCTION With able guidance and leadership of our Chairman Dr. C. Rangarajan and other Board of Governors of Madras School of Economics (MSE), MSE completes its 21 years as on September 23, 2014. During these 21 years, MSE reached many mile stones and emerged as a leading centre of higher learning in Economics. It is the only center in the country offering five specialized Masters Courses in Economics namely M.Sc. General Economics, M.Sc. Financial Economics, M.Sc. Applied Quantitative Finance, M.Sc. Environmental Economics and M.Sc. Actuarial Economics. It also offers a 5 year Integrated M.Sc. Programme in Economics in collaboration with Central University of Tamil Nadu (CUTN). It has been affiliated with University of Madras and Central University of Tamil Nadu for Ph.D. programme. So far twelve Ph.Ds. and 640 M.Sc. students have been awarded. Currently six students are pursuing Ph.D. degree. The core areas of research of MSE are: Macro Econometric Modeling, Public Finance, Trade and Environment, Corporate Finance, Development, Insurance and Industrial Economics. MSE has been conducting research projects sponsored by leading national and international agencies. It has successfully completed more than 110 projects and currently undertakes more than 20 projects. -

Monday, July 12, 2021 Tuesday, July 13, 2021

JULY 12-15, 2021 On Zoom every day during 6:30 to 9:30 pm IST and at equivalent times in other zones (time clock) Participation in the India Policy Forum 2021 is by invitation. Invitations are non-transferable. Click here for Biosketches of the participants MONDAY, JULY 12, 2021 All times are IST 6:30–8:00 pm Welcome Remarks Surjit S Bhalla, Executive Director IMF & Governing Body Member, NCAER Introduction to the 18th India Policy Forum Poonam Gupta, NCAER; Barry Bosworth, Brookings Institution; Karthik Muralidharan, University of California, San Diego & NCAER The 3rd T.N. Srinivasan Memorial Lecture “Responding to COVID-19 amidst Market and Government Failures” Speaker: Shanta Devarajan, Georgetown University & NCAER Chair: Rukmini Banerji, Pratham Education Foundation 8:00–9:30 pm Big, Open Data for Development: A Vision for India [Paper] Sam Asher, Johns Hopkins; Aditi Bhowmick, Development Data Lab; Alison Campion, Development Data Lab; Tobias Lunt, Development Data Lab; Paul Novosad, Dartmouth College, Development Data Lab Chair: Suman Bery, Bruegel & former Director General, NCAER Discussants: Robert J. Cull, World Bank Ashwini Deshpande, Ashoka University TUESDAY, JULY 13, 2021 All times are IST Welcome to the 2nd day of the IPF 2021 & general instructions 6:30–8:00 pm Analysing India's Exchange Rate Regime [Paper] Rajeswari Sengupta, IGIDR; Ila Patnaik, NIPFP Chair: Raghuram Rajan, University of Chicago & former RBI Governor Discussants: Poonam Gupta, NCAER Prakash Loungani, IMF 8:00–9:30 pm IPF POLICY ROUNDTABLE ONE The future of economic reforms: 30 years after “बता तेरी रजा �ा है? (What’s your wish?)” Looking Back to Look Ahead Conversations with four Finance Secretaries on the next round of reforms Moderator: K.P. -

Annual Report 2006-2007

Annual Report 2006-2007 National Institute of Public Finance & Policy New Delhi National Institute of Public Finance and Policy 18/2 Satsang Vihar Marg Special Institutional Area (Near JNU) New Delhi 1100 67. Website: www.nipfp.org.in 1 Overview The year 2006-07 marks the completion of 31 years in the life of National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP). Like in the past, the Institute has continued to make significant contribution to policy research, contemporary policy debate and advocacy, and capacity building. In fulfilling its objectives, NIPFP has continued to assist and guide various central and state governments and expert committees and commissions in analysing and evaluating the existing policies and exploring reform options. The faculty of the Institute has contributed to the work of various policy advisory and expert bodies. The Institute has also undertaken a number of national and international training programmes for government officials and university teachers. An important development during the year was the appointment of a Peer Review Committee by the Ministry of Finance to evaluate the work of the Institute. This was the first review in 30 years and in the report submitted to Ministry of Finance, the Committee states, “…Over the years, NIPFP has established a reputation for research in public economics and fiscal policy.” (Para. 18), “…The research output of the Institute enjoys credibility not only within the policy makers in the Government but also with academia, donor institutions and corporate sector.” (para. 19), “… the Institute has established a reputation for its work in the area of public finance and fiscal policy. -

Tax Planning for Individuals

January 2019 Dear Reader, “Taxes, after all, are dues that we pay for the privileges of membership in an organized society.” These words from Franklin D. Roosevelt capture the essence of tax so well. A tax (from the Latin taxo) is a mandatory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed upon a taxpayer (an individual or other legal entity) by a governmental organization to fund various public expenditures. A failure to pay, along with evasion of or resistance to taxation, is punishable by law. As a responsible citizen, it is very important that we pay our tax dues on time to help our country and economy grow. It is equally important to understand the various avenues readily available to individuals to save tax. With the start of the new financial year around the corner, this issue of ‘The Financial Kaleidoscope’ aims to demystify tax planning for individuals. It is a how-to guide that covers some practices for managing tax liability and the essentials of filing income tax returns. We hope this issue will aid you to invest wisely to embark on a journey of being a financially prudent and socially responsible tax paying citizen. As always, your feedback and comments are welcome. Regards NSDL 1 Basics of Income Tax Planning Definition of ‘Income’ For the purposes of Income Tax, any inflow of money (cash and kind) that a person receives is considered ‘Income’. The Income Tax Act classifies it under five heads: Salaries: All forms of payments received from an employer, such as salary, allowances, perquisites, bonuses as well as pension. -

Curriculum Vitae Sacchidananda Mukherjee

Curriculum Vitae Sacchidananda Mukherjee PRESENT ADDRESS Consultant, Tax Research Unit National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) 18/2, Satsang Vihar Marg, Special Institutional Area (Near JNU) New Delhi – 110067, INDIA. Mobile: +91 9868421239 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION October 2002 – May 2008 (Submitted) Ph.D. in Economics, Madras School of Economics, University of Madras, Chennai. Thesis Topic : Economics of Agricultural Nonpoint Source Water Pollution: A Case Study of Groundwater Nitrate Pollution in the Lower Bhavani River Basin, Tamilnadu. (Environmental Economics) Supervisor : Prof. Paul. P. Appasamy, Vice Chancellor, Karunya University, Coimbatore. July 2001 – September 2002 M. Phil. (Economics) Completed Course Work Only Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. August 1998 – May 2000 M.A. (Economics) Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. July 1995 – August 1998 B.Sc. in Economics (Honours), University of Calcutta. AWARDS, FELLOWSHIPS & GRANTS 2006 : International Water Management Institute (IWMI) – Tata Water Policy Research Program’s the best “Young Scientist Award for the Year 2006” 2006 : Contingency Grant-in-Aid, Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi 2006 : Consulting Grant, International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Colombo, Sri Lanka. 2002 – 2007 : Doctoral Fellowship, Madras School of Economics, Chennai, India. 1994 – 1998 : Student Merit Fellowship (National Scholarship), Ministry of Human Resources Development, Government of India, New Delhi. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCES March 2009 – Present: Consultant , National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), New Delhi (Full Time) September 2008 – February 2009 : Senior Manager - Water Resources and Policy , World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)-India, New Delhi (Full Time) October 2007 – August 2008 : Senior Scientific Officer , International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Hyderabad, India (Full Time). -

Taxation in India Taxation Is an Integral Part of Any Business Structure

DEVISING STRATEGY Taxation in India Taxation is an integral part of any business structure. For successful operation of any business, tax strategy adopted by the ma- nagement plays a significant role. Optimisation of tax strategies would help in enhancing growth and tapping success opportunities in timely manner. Rödl & Partner DEVISING STRATEGY Taxation in India Content We in India 5 How taxes influence businesses? 6 Taxation in India 6 Income Tax Regulations 7 Transfer Pricing Regulations 8 Customs Regulations 9 Goods and Services Tax Regulations 9 Recent Developments under Taxation in India 10 Our Taxation Services 11 Tax Optimisation Advisory 11 Transaction Support Services 12 Cross Border Advisory 13 Compliances and Audits 15 Litigation Support and Representation Services 16 Our Services 20 Our Profile 21 Your Specialists in Germany and India 22 Your Contact in India 23 We in India In 2007 Rödl & Partner opened the first office in India. The most populous democracy in the world remains one of the key growth engines for internationally operating companies. For much needed infrastructure improvements there are interesting entry opportunities but also for the traditional industrial sector, like spectacular large-scale projects of the German economy have recently proven. At our main offices in Delhi, Mumbai and Pune as well as in Chennai, Bangalore, Ahmedabad and in our own India team in Germany, multilingual specialists for foreign investments in India work together to provide holistic advice on all issues of law, taxation, BPO and auditing. The Government of India has declared that the external boundaries of India as depicted in these maps are neither correct nor authentic. -

Working Paper No. 92 India's Fiscal Situation: Is a Crisis Ahead?

CENTER FOR RESEARCH ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND POLICY REFORM Working Paper No. 92 India’s Fiscal Situation: Is a Crisis Ahead? by T. N. Srinivasan* February 2001 Stanford University John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Building 366 Galvez Street | Stanford, CA | 94305-6015 * Samuel C. Park, Jr. Professor of Economics, Yale University 2 INDIA’S FISCAL SITUATION: IS A CRISIS AHEAD? T. N. Srinivasan* Samuel C. Park, Jr. Professor of Economics Yale University September 20, 2000—2 Paper presented at the Center for Research on Economic Development and Policy Reform Conference on Indian Economic Prospects: Advancing Policy Reform Abstract Although, on the surface, the achievements of the Indian economy during the past two decades paint a comforting macroeconomic picture, the accompanying rapid expansion in fiscal deficits is unsustainable. The current fiscal problems existing in the states can be attributed to the increasing subsidies on publicly supplied goods and services, inter-state competition in attracting investment through tax incentives, and overstaffing of administrations and public enterprises. The federal structure of India’s fiscal system also implies difficulties in improving the states’ finances. After discussing ways to reform taxes and expenditure, this paper identifies high explicit and implicit subsidies as a major cause of the fiscal problems at the central and state level. Reducing these subsidies requires far-reaching changes in the domestic political economy. The paper also analyzes the fiscal impact of disinvestment. To achieve the goals of development, fiscal sustainability is indispensable. Although there are some positive signs, a political consensus on and commitment to fiscal reform are yet to emerge. -

Roaring Tiger Or Lumbering Elephant?

aUGUST 2006 ANALYSIS MARK THIRLWELL Roaring tiger or Program Director International Economy lumbering elephant? Tel. +61 2 8238 9060 [email protected] Assessing the performance, prospects and problems of India’s development model.1 In the past, there has been plenty of scepticism about India’s economic prospects: for many, Charles De Gaulle’s aphorism regarding Brazil, that it was a country with enormous potential, and always would be, seemed to apply equally well to the South Asian economy. While the ‘tiger’ economies of East Asia were enjoying economic take-off on the back of investment- and export-led growth, the lumbering Indian elephant seemed set to be a perpetual also-ran in the growth stakes. Yet following a series of reform efforts, first tentatively in the 1980s, and then with much more conviction in the 1990s, the Indian economic model has been transformed, and so too India’s growth prospects. High profile successes in the new economy sectors of information technology (IT) and business process outsourcing (BPO), along with faster economic growth, triggered a widespread rethink regarding India’s economic prospects, and a wave of foreign portfolio investment flowed into Indian markets. Perhaps India was set to be a tiger after all. Yet this new-found optimism received a setback in May and June of this year, when there were sharp falls in Indian stock markets. Had the optimism been overdone, and was another re-rating of India’s economic prospects on the cards? Perhaps India was only a lumbering elephant after all? This paper takes a closer look at the new Indian development model. -

Tax System Reform in India M

Initiative for Policy Dialogue Working Paper Series October 2009 Tax System Reform in India M. Govinda Rao and R. Kavita Rao Tax No part of this working paper may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the Initiative for Policy Dialogue. Tax System Reform in India M. Govinda Rao R. Kavita Rao1 National Institute of Public Finance and Policy Many developing countries have embarked on tax reforms in recent years. Such reforms were motivated both by local factors as well as by rapid internationalization of economic activities. The need to correct fiscal imbalances and the transition from a centralized plan to a market economy were the important local factors hastening tax reforms. Difficulties in compressing expenditures necessitated that tax system reform take an important role in fiscal adjustment strategy. The transition from plan to market required the substitution of administered prices with market determined prices, the replacement of physical controls with financial controls, and the substitution of public enterprise profits with tax revenues. Likewise, tax reforms become imperative in a globalizing environment. Enhancing competitiveness and attracting foreign investment require minimizing both efficiency and compliance costs of the tax system. Globalization also involves loss of revenue from customs, which needs to be replaced with domestic taxes. The Indian tax system too had to be reformed in response to changes in development strategy. In the initial years, tax policy was used as an instrument to achieve a variety of diverse goals which included increasing the level of saving and correcting for inequalities arising from an oligopolistic market structure created by a centralized planning regime, including a licensing system, exchange control, and administered prices (Bagchi and Nayak 1994). -

General Knowledge Objective Quiz

Brilliant Public School , Sitamarhi General Knowledge Objective Quiz Session : 2012-13 Rajopatti,Dumra Road,Sitamarhi(Bihar),Pin-843301 Ph.06226-252314,Mobile:9431636758 BRILLIANT PUBLIC SCHOOL,SITAMARHI General Knowledge Objective Quiz SESSION:2012-13 Current Affairs Physics History Art and Culture Science and Technology Chemistry Indian Constitution Agriculture Games and Sports Biology Geography Marketing Aptitude Computer Commerce and Industries Political Science Miscellaneous Current Affairs Q. Out of the following artists, who has written the book "The Science of Bharat Natyam"? 1 Geeta Chandran 2 Raja Reddy 3 Saroja Vaidyanathan 4 Yamini Krishnamurthy Q. Cricket team of which of the following countries has not got the status of "Test" 1 Kenya 2 England 3 Bangladesh 4 Zimbabwe Q. The first Secretary General of the United Nation was 1 Dag Hammarskjoeld 2 U. Thant 3 Dr. Kurt Waldheim 4 Trygve Lie Q. Who has written "Two Lives"? 1 Kiran Desai 2 Khushwant Singh 3 Vikram Seth 4 Amitabh Gosh Q. The Headquarters of World Bank is situated at 1 New York 2 Manila 3 Washington D. C. 4 Geneva Q. Green Revolution in India is also known as 1 Seed, Fertiliser and irrigation revolution 2 Agricultural Revolution 3 Food Security Revolution 4 Multi Crop Revolution Q. The announcement by the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited Chairmen that India is ready to sell Pressurised 1 54th Conference 2 53rd Conference 3 51st Conference 4 50th Conference Q. A pension scheme for workers in the unorganized sector, launched recently by the Union Finance Ministry, has been named 1 Adhaar 2 Avalamb 3 Swavalamban 4 Prayas Q. -

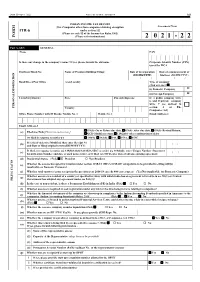

ITR-6 Notified Form AY 2021-22 0.Pdf

[भाग II—ख赍ड 3(i)] भारतकाराजपत्र:असाधारण 343 INDIAN INCOME TAX RETURN [For Companies other than companies claiming exemption Assessment Year ITR-6 under section 11] (Please see rule 12 of the Income-tax Rules,1962) FORM (Please refer instructions) 2 0 2 1 - 2 2 Part A-GEN GENERAL Name PAN Is there any change in the company’s name? If yes, please furnish the old name Corporate Identity Number (CIN) issued by MCA Flat/Door/Block No Name of Premises/Building/Village Date of incorporation Date of commencement of (DD/MM/YYYY) business (DD/MM/YYYY) / / / / Road/Street/Post Office Area/Locality Type of company (Tick any one) (i) Domestic Company (ii) Foreign Company Town/City/District State Pin code/Zip code If a public company write 6, and if private company write 7 (as defined in PERSONAL INFORMATION PERSONAL Country section 3 of The Companies Act) Office Phone Number with STD code/ Mobile No. 1 Mobile No. 2 Email Address-1 Email Address-2 139(1)- On or Before due date, 139(4)- After due date, 139(5)- Revised Return, (a) Filed u/s (Tick)[Please see instruction ] 92CD-Modified return, 119(2)(b)- after condonation of delay Or filed in response to notice u/s 139(9), 142(1), 148, 153A, 153C If revised/ defective/Modified, then enter Receipt No (b) ___ /___/____ and Date of filing original return (DD/MM/YYYY) If filed, in response to notice u/s 139(9)/142(1)/148/153A/153C or order u/s 119(2)(b), enter Unique Number /Document (c) / / Identification Number and date of such notice/order, or if filed u/s 92CD enter date of advance pricing