That Damn Borderline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gösta Neuwirth (*1937)

© Lothar Knessl GÖSTA NEUWIRTH (*1937) Streichquartett 1976 1 Satz I 3:13 2 Satz II 4:36 3 Satz III 4:56 4 Satz IV 4:19 Sieben Stücke für Streichquartett (2008) für Ernst Steinkellner 5 d’accord 1:15 6 pensif 1:22 7 le fils de la fadeur 1:15 8 à trois 1:31 9 objet en ombre 1:06 1 0 un rêve solutréen 0:55 11 l’oubli bouilli 1:28 1 2 L’oubli bouilli (2008) 30:29 TT: 56:25 1 - 4 Annette Bik violin • Gunde Jäch-Micko violin, viola Dimitrios Polisoidis viola • Andreas Lindenbaum violoncello 5 - 11 Sophie Schafleitner violin • Gunde Jäch-Micko violin Dimitrios Polisoidis viola • Andreas Lindenbaum violoncello 5 - 12 Donatienne Michel-Dansac voice Klangforum Wien • Etienne Siebens conductor 5 - 12 Erste Bank Kompositionsauftrag 2 Klangforum Wien Klangforum Wien Vera Fischer Flöte Markus Deuter Oboe Bernhard Zachhuber, Olivier Vivarès Klarinette Gerald Preinfalk Saxophon Edurne Santos Fagott Christoph Walder Horn Anders Nyqvist Trompete Andreas Eberle Posaune Annette Bik, Sophie Schafleitner Violine Dimitrios Polisoidis, Andrew Jezek Viola Benedikt Leitner, Andreas Lindenbaum Violoncello Alexandra Dienz Kontrabass Nathalie Cornevin Harfe Krassimir Sterev Akkordeon Florian Müller Klavier, Keyboards Hsin-Huei Huang Klavier Adam Weisman, Berndt Thurner Schlagwerk Peter Böhm, Florian Bogner Klangregie und Spatialisation 3 Gösta Neuwirths Kopfwelten fehlenden Teile eins und drei lieferte. Lothar Knessl Bildlos sachliche Auskünfte zum Werk bleiben außerhalb der Schublade des Einführungszwan- L’oubli bouilli - Vanish… Ein Titel, der die Frage ges. TEIL I also, zehn Minuten: Primär linear dis- aufwirft: Wohin führen „gekochtes Vergessen und poniertes Gebilde, überwiegend dicht gewebt, Verschwinden“? Sollte sich Vergessen prozessual hie und da solistisch. -

Pierluigi Billone (*1960)

© Benjamin Chelly PIERLUIGI BILLONE (*1960) 1 ITI KE MI for solo viola (1995) 33:11 2 Equilibrio. Cerchio for solo violin (2014) 33:45 TT 67:01 Marco Fusi violin – viola 2 Commissioned by Südwestrundfunk Recording venue: BlowOutStudio (TV-Italy), www.blowoutstudio.it Recording date: 21–22 December 2016 Recording engineer: Luca Piovesan Mixing & Mastering: Luca Piovesan (BlowOutStudio) Graphic Design: Alexander Kremmers (paladino media), cover based on artwork by Erwin Bohatsch 2 3 THE INTERPRETER’S TASK: paths and find something different to do with my life. need to serve as my code of ethics, my armor. In order Beginning the learning process of a difficult new A PERCUSSIONIST’S WITNESSING Upon arriving in Germany, I met a sage who gave to to move forward, I would need to mitigate cognitive piece is comparable to opening the first page of a by Jonathan Hepfer me two pieces of crucial advice: dissonances between my praxis as an artist and the daunting tome. Since it is impossible to divine what person I was in everyday life. This meant undergoing its pages might contain, one must possess a sense of • Slow down my artistic metabolism. a period of dedicated self-cultivation and learning faith in the author of the work that the experience ly- 1. Ethos • Don’t grow my garden wider, but rather, deeper. to choose future repertoire judiciously. Through my ing ahead will be worth one’s time and concentration. work as an interpreter, I would come to know myself. This trust is by necessity based upon intuition. “The wandering, the peregrination toward that which is Not long after consulting this oracle, I attended the Questioning would become homecoming. -

© S Ie G Rid a B Lin G

© Siegrid Ablinger PETER ABLINGER (*1959) Voices and Piano (since 1998) for piano and loudspeaker 1 Bertolt Brecht 2:33 12 Heimito von Doderer 3:09 2 Gertrude Stein 3:44 13 Orson Welles 2:51 3 Lech Walesa 3:01 14 Agnes Gonxha Bojaxiu 1:34 4 Morton Feldman 5:10 (Mother Theresa) 5 Hanna Schygulla 2:37 15 Rolf Dieter Brinkmann 3:39 6 Mao Tse-Tung 6:38 16 Hanns Eisler 3:20 7 Guillaume Apollinaire 3:19 17 Ezra Pound 4:10 8 Bonnie Barnett 3:02 18 Ilya Prigogine 7:34 9 Jean-Paul Sartre 5:41 19 Pier Paolo Pasolini 4:04 10 Martin Heidegger 4:36 11 Marcel Duchamp 4:50 TT: 75:50 Nicolas Hodges piano Recorded: 28-31 March 2005 Thanks to: at ORF Landesstudio Steiermark Deutsches Rundfunk-Archiv, BBC London, Final Mastering: Peter Ablinger Universal Edition London, Arnold Schönberg Center Recording supervisor: Heinz-Dieter Sibitz Wien, IEM Graz, Hanna Schygulla, Nicolas Hodges, Sound technician: Christian Michl Bonnie Barnett, Dr. Jürgen Schebera, Software development: Thomas Musil, Prof. Robert Höldrich, Ursula Block, Thomas Musil, Robert Höldrich, IEM Graz Prof. Ilya Prigogine, Mary de Rachewiltz, Producers: Barbara Fränzen, Peter Oswald Marita Emigholz, Eric Wubbels, Martín Bauer, Artwork: Jakob Gasteiger Mila Haugová, Libgart Schwarz, Michael Pisaro, Graphic Design: Gabi Hauser Franz Reichle, Albert Müller, Mary Lance, Carmen Publisher: Zeitvertrieb Wien Berlin Baliero, Humberto Maturana, among others. C & P 2009 KAIROS Music Production www.kairos-music.com 2 Voices and Piano Peter Ablinger Information IST Redundanz: „Die Tautologie sagt laut Wittgenstein nichts aus über die Welt und hält keinerlei Bezie- hung zu ihr (Tractatus). -

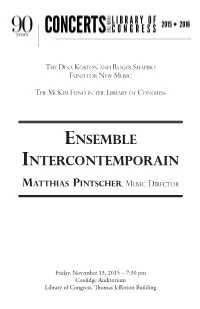

Ensemble Intercontemporain Matthias Pintscher, Music Director

Friday, November 6, 2015, 8pm Hertz Hall Ensemble intercontemporain Matthias Pintscher, Music Director PROGRAM Marco Stroppa (b. 1959) gla-dya. Études sur les rayonnements jumeaux (2006–2007) 1. Languido, lascivo (langoureux, lascif) 2. Vispo (guilleret) 3. Come una tenzone (comme un combat) 4. Lunare, umido (lunaire, humide) 5. Scottante (brûlant) Jens McManama, horn Jean-Christophe Vervoitte, horn Frank Bedrossian (b. 1971) We met as Sparks (2015) United States première Emmanuelle Ophèle, bass flute Alain Billard, contrabass clarinet Odile Auboin, viola Éric-Maria Couturier, cello 19 PROGRAM Beat Furrer (b. 1954) linea dell’orizzonte (2012) INTERMISSION Kurt Hentschläger (b. 1960)* Cluster.X (2015) Edmund Campion (b. 1957) United States première Kurt Hentschläger, electronic surround soundtrack and video Edmund Campion, instrumental score and live processing Jeff Lubow, software (CNMAT) * Audiovisual artist Kurt Hentschläger in collaboration with composer Edmund Campion. Ensemble intercontemporain’s U.S. tour is sponsored by the City of Paris and the French Institute. Additional support is provided by the FACE Foundation Contemporary Music Fund. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsor Ross Armstrong, in memory of Jonas (Jay) Stern. Hamburg Steinway piano provided by Steinway & Sons of San Francisco. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PLAYBILL ORCHESTRA ROSTER ENSEMBLE INTERCONTEMPORAIN Emmanuelle Ophèle flute, bass flute Didier Pateau oboe Philippe Grauvogel oboe Jérôme Comte clarinet Alain -

LUIGI NONO La Lontananza Nostalgica Utopica Futura

LUIGI NONO La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura Marco Fusi Pierluigi Billone © Grazia Lissi Luigi Nono (1924 – 1990) La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura (1988/89) Madrigale per più “caminantes” con Gidon Kremer, violino solo, 8 nastri magnetici, da 8 a 10 leggii 1 Leggio I 09:26 2 Leggio II 12:23 3 Leggio III 10:11 4 Leggio IV 07:36 5 Leggio V 11:19 6 Leggio VI 10:13 TT 61:12 Marco Fusi, violin Pierluigi Billone, sound direction 3 Proximity, Distance our interpretative approach to Luigi Nono’s La Lontananza Nostalgica Utopica Futura The violin my eyes, Nono acknowledged these Playing La lontananza nostalgica sounds, giving them a right to exist, to utopica futura has been a goal of mine be perceived and celebrated in their for several years. Deeply fascinated fragile beauty. Through our training, vi- by the openness of this work and the olin players learn how important these astonishing range of possibilities con- small sounds are, accentuating, hid- tained within the performing materials, ing or playing with them, crafting and the violin manuscript feels charged developing our personal instrumental with an incredibly physical and tactile colour, through a combination of au- description of sonic states. Nono per- ral and tactile connections with the sistently demands an almost inaudible instrument. Every performance on a sound creation, echoing an unstable violin implies an active and highly re- inner voice, clearly indicating an in- fined motoric control of the instrument, strumental approach focused towards where the fingertips of both hands are the “interior identity” of the instru- in dialogue with the materiality of the ment, towards a personal exploration strings and bow. -

Enno Poppe JACK Quartet Yarn / Wire

Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season Composer Portraits Enno Poppe JACK Quartet Yarn / Wire Saturday, February 23, 8:00 p.m. Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season Composer Portraits En n o Po p p e JACK Quartet Yarn / Wire Saturday, February 23, 8:00 p.m. Rad (2003) Enno Poppe (b. 1969) for two keyboards Laura Barger and Ning Yu, keyboards Schweiss (2010) for cello and electric organ Kevin McFarland, cello Laura Barger, keyboard Tier (2002) for string quartet JACK Quartet INTERMISSION Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season On-stage discussion with Enno Poppe and Kevin McFarland Tonband (2008/2012) world premiere Wolfgang Heiniger / Poppe for two keyboards, two percussionists, and live electronics Yarn / Wire This program runs approximately one hour and 45 minutes, including a brief intermission. Major support for Composer Portraits is provided by the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. Composer Portraits is presented with the friendly support of Please note that photography and the use of recording devices are not permitted. Remember to turn off all cellular phones and pagers before tonight’s performance begins. Miller Theatre is wheelchair accessible. Large print programs are available upon request. For more information or to arrange accommodations, please call 212-854-7799. About the Program Introduction Born in the small town of Hemer in western Germany in 1969, Poppe writes music that is at once natural and weird (as perhaps nature is). A piece by him will generally start out from a very small idea, or perhaps more than one, which will then be progressively varied, extended, and repeated, following rules of change similar to those by which, say, a fern frond unfurls and grows. -

Clara Iannotta

Clara Iannotta MOULT Clara Iannotta 1 Clara Iannotta: MOULT 1. MOULT (2018 –19) 17:03 5 for chamber orchestra WDR Sinfonieorchester, conducted by Michael Wendeberg 2. paw-marks in wet cement (ii) (2015–18) 14:23 for piano, two percussionists and amplifi ed ensemble L’Instant Donné, Wilhem Latchoumia, conducted by Aurélien Azan-Zielinski 3. Troglodyte Angels Clank By (2015) 11:4 4 for amplifi ed ensemble Klangforum Wien, conducted by Enno Poppe 4. dead wasps in the jam-jar (ii) (2016) 14:44 for string orchestra, objects and sine waves Münchener Kammerorchester, conducted by Clemens Schuldt Total length: 58:32 Refl ecting Rooms 6 ‘Six Memos for the Next Millennium’ (Lezioni americane: Sei proposte per il prossimo millennio) is how Italo Calvino named his discourses for the Charles Elliot Norton Lectures at Harvard University, in which he wanted to defi ne the outlines of a possible poetics of literature. Condensing each to a single keyword, they promote lightness, quickness, visibility, exactitude and multiplicity as characteristics of art. Calvino’s sudden death left them unfi nished and simmering. However, this did not reduce their infl uence, which reached far beyond the world of literature: for example, Clara Iannotta references the signifi cance that Calvino’s concisely formulated thoughts have for her own artistic thinking. They are a stimulus and a challenge to her in equal measure. Her creativity is not based on a discursive order, on the provision of a narrative thread or the linear development of characters and fi gures. Clara Iannotta’s compositions do not tell a story, but rather develop a physiognomy. -

© Jin O H a Si

© Jin Ohasi DAI FUJIKURA (*1977) www.daifujikura.com ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble) 1 Sparks (2011) 1:25 4 Abandoned Time (2004–06) 8:57 Erik Carlson violin 2 for solo guitar for solo electric guitar and ensembles David Bowlin violin 4 Wendy Richman viola 2 2 ice (2009–10) 21:17 5 I dreamed on singing flowers (2012) 4:22 Maiya Papach viola 4 for ensemble for prerecorded electronics Kivie Cahn-Lipman cello 2 Katinka Kleijn cello 4 3 Phantom Splinter (2009) 22:53 6 Sparking Orbit (2013) 17:18 Randall Zigler double bass 2 4 for ensemble and live electronics for solo electric guitar and live electronics Claire Chase flute/alto flute/bass flute 2 flute 4 Eric Lamb flute/alto flute/piccolo 2 solo guitar International Contemporary Ensemble · Daniel Lippel TT: 1:16:12 Nicholas Masterson oboe 2 3 Jayce Ogren · Matthew Ward Rebekah Heller bassoon 2 3 Joshua Rubin clarinet 2 3 1 2 Recording: Ryan Streber, Daniel Lippel; Ryan Streber, Jacob Greenberg, Dai Fujikura; Daniel Lippel guitar 1 2 · electric guitar 4 6 3 4 Joachim Haas, Thomas Hummel, Teresa Carasco; Ryan Streber Cory Smythe piano 4 5 Dai Fujikura; 6 Michael Acker, Dai Fujikura Nathan Davis percussion Recording venues: 1 2 Oktaven Audio, Yonkers, New York, USA; 3 6 SWR, Freiburg, Germany David Schotzko percussion 4 (EXPERIMENTALSTUDIO of the SWR); 4 Sweeney Auditorium, Smith College, Northampton, Ryan Streber engineer, digital editor, post-production Massachusetts, USA Jacob Greenberg producer Recording dates: 1 17 March 2013; 2 8 June 2012; 3 16–17 March 2011; 4 26 August 2007; -

REBECCA SAUNDERS — Solo

REBECCA SAUNDERS Solo Klangforum Wien © Astrid Ackermann Rebecca Saunders (*1967 ) 1 Shadow ( 2013 ) study for piano 11:42 2 Dust ( 2017/18 ) for percussion solo 07:37 3 Solitude ( 2013 ) for solo violoncello 19:00 4 Flesh ( 2018 ) Solo for accordion with recitation 09:28 5 Hauch ( 2018 ) for violin solo 08:09 6 to an utterance – study ( 2020 ) for solo piano 11:16 Commissioned by Klangforum Wien and funded by the Ernst von Siemens Musikstiftung 1 Florian Müller, piano 2 Björn Wilker, percussion 3 Andreas Lindenbaum, violoncello 4 Krassimir Sterev, accordion 5 Sophie Schafleitner,violin TT 67:16 6 Joonas Ahonen, piano 3 “Everything is already here. I simply provide a frame, a context. The world is so saturated with noise. To filter out the nuances, or to exclude certain fragments, stands at the beginning of my work process. But it’s not the beginning of a piece.” Rebecca Saunders Solo pieces occupy an important place in Rebecca Saunders’ oeu- vre, since at least during the prepara- tion period, the composer’s solitude is transformed into a dialogue with the soloists with whom she seeks a close collaboration; the sheer physicali- ty of their playing providing a source of lasting inspiration to the composer. She deeply explores the world of the sounds, offering a declaration of love to the respective instrument, soloist or to music in general. Dust is a solo for two, a homage to both Christian Dierstein and Dirk Rothbrust, because each of them has created his own version of this piece with and by Rebecca Saunders. -

0013152KAI.Pdf

FRIEDRICH CERHA (*1926) 1 Bruchstück, geträumt (2009) 18:41 11 - 12 Instants (2006/07) 33:50 for ensemble for orchestra commissioned by Wittener Tage für neue Kammermusik commissioned by WDR 2 - 10 Neun Bagatellen (2008) 14:16 11. Teil I 15:32 for string trio 12. Teil II 18:18 commissioned by WDR 2. adirato, marcato 0:42 TT: 66:47 3. Malinconia I 2:34 4. senza titolo 0:58 Klangforum Wien 5. senza titolo 1:11 Sylvain Cambreling conductor 6. capriccioso 1:02 Zebra Trio 7. Malinconia II 3:01 WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln 8. molto leggiero 1:18 Peter Rundel conductor 9. molto calmo 1:55 10. con ostinatezza 1:35 Recording venues: 1 Konzerthaus Wien, Mozart-Saal, 2 - 10 ORF Steiermark, Studio 3, 11 - 12 Kölner Philharmonie Recording dates: 1 18.6.2010, 2 - 10 8.8.2010, 11 - 12 14.11.2009 Recording producers: 1 Florian Rosensteiner, 2 - 10 Heinz Dieter Sibitz, 11 - 12 Christian Schmitt Digital mastering and mixing: 1 Peter Böhm, Florian Bogner Recording engineers: 1 Robert Pavlecka, 2 - 10 Gerhard Hüttl, 11 - 12 Christoph Gronarz Recording assistants: 1 Christian Gorz, 11 - 12 Renate Reuter Final mastering: Christoph Amann Executive producers: Harry Vogt, Barbara Fränzen, Peter Oswald Cover-Artwork: Karl Prantl, „Stein für Friederich Cerha“ 1984-1987 Krastaler Marmor 130 x 190 x 870 cm, Standort: Pötschinger Feld Photography: Lukas Dostal, www.lukasdostal.at C & P 2011 KAIROS Production www.kairos-music.com 2 Klangforum Wien Christoph Walder horn Reinhard Zmölnig horn Andreas Eberle trombone Sophie Schafleitner violine Annette Bik violine Annelie -

Program Booklet

THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC THE MCKIM fUND IN THE LIBRARY oF CONGRESS ENSEMBLE INTERCONTEMPORAIN MATTHIAS PINTSCHER, MUSIC DIRECTOR Friday, November 13, 2015 ~ 7:30 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports the commissioning and performance of contemporary music. The MCKIM FUND in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson; the fund supports the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. Harpsichord by Thomas and Barbara Wolf, 1991, after Pascal Taskin, 1770 Special thanks to "The President's Own" United States Marine Band for the loan of several musical instruments A live recording of the premiere performances of the Library's commissioned works by Hannah Lash and Matthias Pintscher will be available at q2music.org/libraryofcongress, as part of the ongoing collaboration between the Library of Congress and Q2 Music. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. -

CV Apr 2018 EN Foto

DR. MARK BARDEN SONNENALLEE 97, 12045 BERLIN [email protected] • +49 1522 3000 562 www.mark-barden.com EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy Composition, 2011–17 Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Roger Redgate, Advisor 1 Diplom Künstlerische Ausbildung Composition, 2007–10 (German equivalent to US Master's Degree) Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, Germany Mathias Spahlinger & Jörg Widmann, Teachers Private Lessons Composition, 2005–07 Rebecca Saunders, Teacher Bachelor of Music Composition & Piano Performance, 1998–2003 Oberlin Conservatory of Music, USA Lewis Nielson & Monique Duphil, Teachers COMMISSIONS (SELECTION) 2019 Witten Festival, Ensemblekollektiv Berlin 2018 Arditti Quartet, Solistenensemble Kaleidoskop 2017 Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts (for Séverine Ballon & Ashot Sarkissjan) 2016 Éclat Stuttgart (für Nicolas Hodges), Ensemble Aventure 2015 Donaueschingen Festival, Goethe Institute Chicago, Acht Brücken Festival 2014 Radio France (Présences Festival, Paris), Munich Biennale (Klangspuren) 2013 Ensemble Intercontemporain (Paris), Wien Modern (Vienna) 2012 Donaueschingen Festival, Darmstadt Summer Courses, Witten Festival 2011 Academy of the Arts Berlin, poesiefestival berlin 2010 Ensemble Recherche, Freiburg Baroque Orchestra FELLOWSHIPS & AWARDS (SELECTION) 2017 Academy of the Arts Berlin, Studio for Electronic Music: Composer Residency 2016 Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts: Composition Commission Prize 2016 Berlin Senate: Composer Residency at the German Studies Center in Venice 2015 Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation: Composer's