Program Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mercredi 25 Avril 2012 Nora Gubisch | Ensemble Intercontemporain | Alain Altinoglu

Roch-Olivier Maistre, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Mercredi 25 avril 2012 avril 25 Mercredi | Mercredi 25 avril 2012 Nora Gubisch | Ensemble intercontemporain | Alain Altinoglu Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.citedelamusique.fr Altinoglu | Alain Gubisch | Ensemble intercontemporain Nora 2 MERCREDI 25 AVRIL – 20H Salle des concerts Lu Wang Siren Song Igor Stravinski Huit Miniatures instrumentales Concertino pour douze instruments Maurice Ravel Trois Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé entracte Marc-André Dalbavie Palimpseste Luciano Berio Folk Songs Nora Gubisch, mezzo-soprano Ensemble intercontemporain Alain Altinoglu, direction Diffusé en direct sur les sites Internet www.citedelamusiquelive.tv et www.arteliveweb.com, ce concert restera disponible gratuitement pendant trois mois. Il est également retransmis en direct sur France Musique. Coproduction Cité de la musique, Ensemble intercontemporain. Fin du concert vers 22h15. 3 Lu Wang (1982) Siren Song Composition : 2008. Création : 5 avril 2008 à New York, Merkin Concert Hall, par l’International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), sous la direction de Matt Ward. Effectif : flûte / flûte piccolo, clarinette en si bémol / clarinette en mi bémol / clarinette basse – cor, trompette – piano – harpe – percussions – violon, alto, violoncelle. Éditeur : inédit. Durée : environ 7 minutes. Cette pièce peut être vue comme un court opéra. Elle utilise la translittération d’un ancien dialecte de Xi’an, ma ville natale, extrêmement puissant et musical qui, dans le parlé/chanté, se déploie en intervalles démesurés et en glissandi. J’avais été particulièrement fascinée par une voix que j’entendis chez un conteur qui chantait dans ce dialecte : c’était la voix sèche, comme affolée et pourtant très séduisante d’un vieil eunuque. -

Orchestre De Paris Asume El Papel De Asesor Artístico En 2020/2021 Y Será Su Próximo Director Musical a Partir De Septiembre De 2022

70 Festival de Granada Biografías Klaus Mäkelä Klaus Mäkelä es director principal y asesor artístico de la Filarmónica de Oslo. Con la Orchestre de Paris asume el papel de asesor artístico en 2020/2021 y será su próximo director musical a partir de septiembre de 2022. Es, además, director invitado principal de la Orquesta Sinfónica de la Radio Sueca y director artístico del Festival de Música de Turku. Como artista exclusivo de Decca Classics, Klaus Mäkelä ha grabado el ciclo completo de sinfonías de Sibelius con la Filarmónica de Oslo como primer proyecto con el sello, que será editado en la primavera de 2022. Klaus Mäkelä inaugura la temporada 2021/2022 de la Filarmónica de Oslo este mes de agosto con un concierto especial interpretando el Divertimento de Bartók, el Concierto para piano nº 1 con Yuja Wang como solista, dos obras de estreno del compositor noruego Mette Henriette y Lemminkäinen de Sibelius. Ofrecerá un repertorio de similar amplitud durante su segunda temporada en Oslo., incluyendo las grandes obras corales de J. S Bach, Mozart y William Walton, la Sinfonía nº 3 de Mahler y las nº 10 y 14 de Shostakóvich con los solistas Mika Kares y Asmik Grigorian. Entre las obras contemporáneas y de estreno se incluyen composiciones de Sally Beamish, Unsuk Chin, Jimmy Lopez, Andrew Norman y Kaija Saariaho. En la primavera de 2022, Klaus Mäkelä y la Filarmónica de Oslo interpretarán las sinfonías completas de Sibelius en la Wiener Konzerthaus y la Elbphilharmonie de Hamburgo, y en gira por Francia y el Reino Unido. Con la Orchestre de Paris, visitará los festivales de verano de Granada y Aix-en- Provence. -

Karl Schuricht Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op

Karl Schuricht Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre Country: France Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1276 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1586 mb WMA version RAR size: 1954 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 930 Other Formats: XM AA APE FLAC AIFF ASF WAV Tracklist Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre A1 Allegro Non Troppo (Cadence De Kreisler) B1 Adagio Allegro Giocoso, Ma Non Troppo Vivace (Cadence De B2 Kreisler) Companies, etc. Printed By – Dehon & Cie Imp. Paris Credits Liner Notes – Claude Rostand Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: DP Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Johannes Brahms, Johannes Brahms, Christian Ferras, Christian Ferras, Wiener Philharmoniker, LXT 2949 Wiener Carl Schuricht - Decca LXT 2949 UK Unknown Philharmoniker, Carl Concerto In D Major For Schuricht Violin And Orchestra Opus 77 (LP, Album) Carl Schuricht - Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Christian Ferras - 6.42142 Johannes Brahms - 6.42142 Johannes Brahms - Decca Germany Unknown AF Wiener Philharmoniker - AF Wiener Violinkonzert D-Dur (LP, Philharmoniker Album) Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Carl Schuricht - Johannes Brahms - Christian Ferras - Wiener Philharmoniker - LXT 2949 Johannes Brahms - Decca LXT 2949 Spain 1958 Concierto En "Re" Wiener Mayor Para Violín y Philharmoniker Orquesta Opus 71 (LP, Album, Mono) Johannes Brahms, Christian Ferras, Vienna Johannes Brahms, Philharmonic Christian Ferras, Orchestra*, Carl B 19018 Vienna Philharmonic Richmond B 19018 Mexico Unknown Schuricht - Concerto In Orchestra*, Carl D Major For Violin And Schuricht Orchestra Opus 77 (LP, Album) Carl Schuricht - Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Christian Ferras - LW 50095 Johannes Brahms - Johannes Brahms - Decca LW 50095 Germany Unknown Wiener Wiener Philharmoniker - Philharmoniker Violinkonzert D-Dur (LP) Related Music albums to Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. -

6 Program Notes

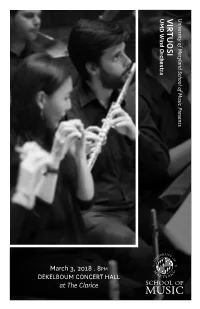

UMD Wind OrchestraUMD VIRTUOSI University Maryland of School Music of Presents March 3, 2018 . 8PM DEKELBOUM CONCERT HALL at The Clarice University of Maryland School of Music presents VIRTUOSI University of Maryland Wind Orchestra PROGRAM Michael Votta Jr., music director James Stern, violin Audrey Andrist, piano Kammerkonzert .........................................................................................................................Alban Berg I. Thema scherzoso con variazioni II. Adagio III. Rondo ritmico con introduzione James Stern, violin Audrey Andrist, piano INTERMISSION Serenade for Brass, Harp,Piano, ........................................................Willem van Otterloo Celesta, and Percussion I. Marsch II. Nocturne III. Scherzo IV. Hymne Danse Funambulesque .....................................................................................................Jules Strens I wander the world in a ..................................................................... Christopher Theofanidis dream of my own making 2 MICHAEL VOTTA, JR. has been hailed by critics as “a conductor with ABOUT THE ARTISTS the drive and ability to fully relay artistic thoughts” and praised for his “interpretations of definition, precision and most importantly, unmitigated joy.” Ensembles under his direction have received critical acclaim in the United States, Europe and Asia for their “exceptional spirit, verve and precision,” their “sterling examples of innovative programming” and “the kind of artistry that is often thought to be the exclusive -

Digibooklet Antonio Janigro

ANTONIO JANIGRO & ZAGREG SOLOISTS Berlin, 1957-1966 ARCANGELO CORELLI (1653-1713) Concerto grosso in D major, Op. 6/4 I. Adagio – Allegro 2:32 II. Adagio 2:03 SOLOISTS III. Vivace 1:09 IV. Allegro – 1:58 V. Allegro 0:41 Gunhild Stappenbeck, Cembalo Continuo recording: 14-01-1957 GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792-1868) Sonata for Strings No. 6 in D major I. Allegro spiritoso 6:32 II. Andante assai 2:39 ZAGREG III. Tempesta. Allegro 5:12 recording: 19-04-1964 & PAUL HINDEMITH (1895-1963) Trauermusik (Funeral Music) for Solo Viola and Strings I. Langsam 4:28 II. Ruhig bewegt 1:25 III. Lebhaft 1:32 IV. Choral „Für deinen Thron“ 2:24 Stefano Passaggio, solo viola recording: 12-03-1958 JANIGRO DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Octet for Strings, Op. 11 II. Scherzo recording: 17-04-1964 SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) Adagio for Strings recording: 19-04-1964 ANTONIO ANTONIO MILKO KELEMEN (*1924) Concertante Improvisations for Strings I. Allegretto 2:20 II. Andante sostenuto – Allegro giusto 2:05 SOLOISTS III. Allegro scherzando 1:15 IV. Molto vivace quasi presto 2:05 recording: 12-03-1958 MAX REGER (1873-1916) Lyric Andante for String Orchestra5:18 recording: 16-03-1966 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Divertimento in B-flat major, K. 137 ZAGREG I. Andante 4:10 II. Allegro di molto 2:44 & III. Allegro assai 2:17 recording: 19-03-1961 ROMAN HOFFSTETTER (1742-1815), former attrib. to JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809) Serenade in C major (from Op. 3/5) recording: 11-11-1958 ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Concerto in D major, RV 230 (Cello Version) JANIGRO I. -

Isang Yun World Premiere: 06 Nov 1983 Trossingen, Germany Hugo Noth, Accordion; Joachim-Quartett

9790202514955 Accordion, String Quartet Isang Yun World Premiere: 06 Nov 1983 Trossingen, Germany Hugo Noth, accordion; Joachim-Quartett Contemplation 1988 11 min for two violas 9790202516089 2 Violas Isang Yun photo © Booseyprints World Premiere: 09 Oct 1988 Philharmonie, Kammermusiksaal, Berlin, Germany Eckart Schloifer & Brett Dean ENSEMBLE AND CHAMBER WITHOUT VOICE(S) Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Bläseroktett Distanzen 1993 18 min 1988 16 min for wind octet with double bass ad lib. for wind quintet and string quintet 2ob.2cl.2bn-2hn-db(ad lib) 9790202516409 (Full score) 9790202518427 (Full score) World Premiere: 09 Oct 1988 World Premiere: 19 Feb 1995 Philharmonie, Kammermusiksaal, Berlin, Germany Stuttgart, Germany Scharoun Ensemble Stuttgarter Bläserakademie Conductor: Heinz Holliger Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Bläserquintett Duo for cello and harp 1991 16 min 1984 13 min for wind quintet (or cello and piano) fl.ob.cl.bn-hn 9790202514986 Cello, Harp 9790202580790 Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Bassoon, Horn (score & parts) 9790202580806 Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Horn, Bassoon (Full Score) World Premiere: 27 May 1984 Ingelheim, Germany Ulrich Heinen, cello / Gerda Ockers, harp World Premiere: 06 Aug 1991 Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival, Altenhof bei Kiel, Germany Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Albert Schweitzer Quintett Espace II Concertino 1993 13 min 1983 17 min for cello, harp and oboe (ad lib.) for accordion and string quartet 9790202517475 Cello, Harp, (optional Oboe) 9790202518700 Accordion, String Quartet (string parts) World Premiere: 17 Sep 1993 St. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

Pianist MARINO FORMENTI to Perform Solo Recital LISZT INSPECTIONS Music by Franz Liszt Juxtaposed with Works by Modern and Contemporary Masters

Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] National Press Representative: Julia Kirchhausen (917) 453-8386; [email protected] Lincoln Center Contact: Eileen McMahon (212) 875 -5391; [email protected] JUNE 4, 2014, AT LINCOLN CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS IN THE STANLEY H. KAPLAN PENTHOUSE: Pianist MARINO FORMENTI To Perform Solo Recital LISZT INSPECTIONS Music by Franz Liszt Juxtaposed with Works by Modern and Contemporary Masters As part of the NY PHIL BIENNIAL, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts will present an intimate concert featuring Italian pianist Marino Formenti, June 4, 2014, at Lincoln Center’s Stanley H. Kaplan Penthouse, on its Great Performers series. The solo recital, Liszt Inspections, will provide a fresh look at the work of Franz Liszt (Hungary, 1811–86) and his sonic legacy by juxtaposing performances of his compositions with those of modern and contemporary masters. Complimentary wine will be served. Marino Formenti said: “This program explores the astonishing and prophetic aspects in the music of Liszt, who foresaw not only atonality, but also dodecaphony, spatial music, music without development, concept music, and minimalist music. By joining works of the 19th-century Hungarian Liszt with 20th-century mavericks, I have attempted to inspect, examine, and reveal multifarious and enlightening relationships and show how beautiful and timeless modern music can be. I am honored to contribute to the first-ever NY PHIL BIENNIAL.” The program will feature Liszt’s Hungarian Folksong No. 5, Piano Piece No. 2 in A-flat major, Bagatelle without tonality, Michael Mosonyi, Funérailles, Au lac de Wallenstadt, Lullaby, and Resignation. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Piano Tamara Stefanovich, Piano

Thursday, March 12, 2015, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano Tamara Stefanovich, piano The Piano Music of Pierre Boulez PROGRAM Pierre Boulez (b. 1925) Notations (1945) I. Fantastique — Modéré II. Très vif III. Assez lent IV. Rythmique V. Doux et improvisé VI. Rapide VII. Hiératique VIII. Modéré jusqu'à très vif IX. Lointain — Calme X. Mécanique et très sec XI. Scintillant XII. Lent — Puissant et âpre Boulez Sonata No. 1 (1946) I. Lent — Beaucoup plus allant II. Assez large — Rapide Boulez Sonata No. 2 (1947–1948) I. Extrêmement rapide II. Lent III. Modéré, presque vif IV. Vif INTERMISSION PLAYBILL PROGRAM Boulez Sonata No. 3 (1955–1957; 1963) Formant 3 Constellation-Miroir Formant 2 Trope Boulez Incises (1994; 2001) Boulez Une page d’éphéméride (2005) Boulez Structures, Deuxième livre (1961) for two pianos, four hands Chapitre I Chapitre II (Pièces 1–2, Encarts 1–4, Textes 1–6) Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ – Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsor Françoise Stone. Hamburg Steinway piano provided by Steinway & Sons, San Francisco. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES PROGRAM NOTES THE PROGRAM AT A GLANCE the radical break with tradition that his music supposedly embodies. If Boulez belongs to an Tonight’s program includes the complete avant-garde, it is to a French avant-garde tra - piano music of Pierre Boulez, as well as a per - dition dating back two centuries to Berlioz formance of the second book of Structures for and Delacroix, and his attitudes are deeply two pianos. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Chamber Music Handbook 2019–20 2 Office Staff

INSTRUMENTAL CHAMBER MUSIC HANDBOOK 2019–20 2 OFFICE STAFF David Geber, Artistic Advisor to Chamber Music Katharine Dryden, Managing Director of Instrumental Ensembles [email protected] 917 493-4547 Office: Room 211 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 Who is required to take chamber music? 5 Semester overview 6 Chamber music class policies 7 Beginning-of-semester checklist 9 End-of-semester checklist 10 How to make future group requests 11 Chamber music competitions at MSM 13 Chamber music calendar for 2019-20 14 Chamber music faculty 17 Table of chamber music credit requirements 18 3 INTRODUCTION Chamber music is a vital part of study and performance at Manhattan School of Music. Almost every classical instrumentalist is required to take part in chamber music at some point in each degree program. Over 100 chamber ensembles of varying size and instrumentation are formed each semester. The chamber music faculty includes many of the School’s most experienced chamber musicians, including current or former members of the American, Brentano, Juilliard, Mendelssohn, Orion and Tokyo string quartets, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, and Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, among others. Our resident ensembles, American String Quartet and Windscape, also coach and give seasonal performances. Masterclasses given by distinguished artists are available to chamber groups by audition or nomination from the chamber music faculty. In addition to more traditional ensembles, Baroque Aria Ensemble is offered in fulfillment of one semester of instrumental chamber music. Pianists may earn chamber music credit from participation in standard chamber groups or two-piano teams. Other options for pianists include participation in the following chamber music classes: the Instrumental Accompanying Class (IAC), vocal accompanying classes including Russian Romances and Ballads and Songs of the Romantic Period, and Approaches to Chamber Music for Piano and Strings.