The Pontifical Institute of Oriental Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EPISTLE St

THE EPISTLE St. Philip’s Episcopal Church 342 East Wood Street Palatine, Illinois 60067-5357 (847) 358-0615 www.stphilipspalatine.org http://www.facebook.com/stphilipspalatine The Rev. Jim Stanley, Rector Dear friend in Christ, What does your faith in Jesus mean to you? Has your Christian faith seen you through some tough times? Does the knowledge that you are "sealed by the Holy Spirit in Baptism and marked as Christ's own forever" (BCP p. 308) bring you hope and comfort for your future? Have there been times when a particular passage of Scripture has lifted you? I'm sure most people reading this know exactly what I mean. I don't want us to simply stop with being grateful for our faith. Be thankful, yes; but the same Lord who has so comforted and encouraged us, has also urged us to serve others. Jesus expects us to work for justice and peace. We are to feed the hungry, advocate for the poor, comfort the widow and orphan. May we never lose sight of this Great Commandment to do to others as we would have done to ourselves! In addition to leaving us with a Great Commandment, our Lord also assigned us a Great Commission. Just before He ascended to His Father in Heaven, Jesus told His disciples -- 1 and by extension, all who would come to believe in Him in the future -- to "Go into all the world and proclaim His Good News, making disciples of all nations and baptizing in the Name of the Holy Trinity." Jesus ordered that His message be taken "to the uttermost parts of the earth". -

The Latin Mass Society

Ordo 2010 Compiled by Gordon Dimon Principal Master of Ceremonies assisted by William Tomlinson for the Latin Mass Society © The Latin Mass Society The Latin Mass Society 11–13 Macklin Street, London WC2B 5NH Tel: 020 7404 7284 Fax: 020 7831 5585 Email: [email protected] www.latin-mass-society.org INTRODUCTION +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Omnia autem honeste et secundum ordinem fiant. 1 Cor. 14, 40. This liturgical calendar, together with these introductory notes, has been compiled in accordance with the Motu Proprio Rubricarum Instructum issued by Pope B John XXIII on 25th July 1960, the Roman Breviary of 1961 and the Roman Missal of 1962. For the universal calendar that to be found at the beginning of the Roman Breviary and Missal has been used. For the diocesan calendars no such straightforward procedure is possible. The decree of the Sacred Congregation of Rites of 26th July 1960 at paragraph (6) required all diocesan calendars to conform with the new rubrics and be approved by that Congregation. The diocesan calendars in use on 1st January 1961 (the date set for the new rubrics to come into force) were substantially those previously in use but with varying adjustments and presumably as yet to re-approved. Indeed those calendars in use immediately prior to that date were by no means identical to those previously approved by the Congregation, since there had been various changes to the rubrics made by Pope Pius XII. Hence it is not a simple matter to ascertain in complete and exact detail the classifications and dates of all diocesan feasts as they were, or should have been, observed at 1st January 1961. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

Annual Palm Sunday Seafood Dinner 6:30 P.M

Saint John the Baptist Orthodox Church, Rochester NY Great Lent, Holy Week, PASCHA: 2017 Schedule of Services First Week of Great Lent: Orthodoxy 27 February (Monday) 6:30 p.m. Compline & Canon of St. Andrew of Crete 28 February (Tuesday) 6:30 p.m. Compline & Canon of St. Andrew of Crete 1 March (Wednesday) 7:15 a.m. Daily Lenten Matins 6:30 p.m. Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts 2 March (Thursday) 6:30 p.m. Compline & Canon of St. Andrew of Crete 3 March (Friday) 12:15 p.m. Akathist: To the Divine Passion of Christ 5:15 p.m. Akathist: In Preparation for Holy Communion 4 March (Saturday) 5:00 p.m. Great Vespers; General Confession 5 March (Sunday) 10:00 a.m. Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great 5:00 p.m. Sunday of Orthodoxy Vespers ~ Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church Second Week of Great Lent: Saint Gregory Palamas 8 March (Wednesday) 7:15 a.m. Daily Lenten Matins 6:30 p.m. Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts 10 March (Friday) 12:15 p.m. Akathist: In Preparation for Holy Communion 5:15 p.m. Akathist: To the Divine Passion of Christ 11 March (Saturday) 4:30 p.m. Panikheda (memorial) for the departed 5:00 p.m. Great Vespers; individual confessions 12 March (Sunday) 10:00 a.m. Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great Third Week of Great Lent: The Veneration of the Cross 15 March (Wednesday) 7:15 a.m. Daily Lenten Matins 6:30 p.m. Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts 17 March (Friday) 12:15 p.m. -

Narthex of the Deaconesses in the Hagia Sophia by Neil K. Moran Abstract

Narthex of the Deaconesses in the Hagia Sophia by Neil K. Moran Neil K. Moran received a Dr.phil. from Universität Hamburg, Germany, in 1975, and completed a fellowship at Harvard’s Center for Byzantine Studies in 1978. He also holds a B.Mus. from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and a M.A. from Boston University. He is the author/co-author of six books, and 37 articles and reviews that can be found on academia.edu. Abstract: An investigation of the ceiling rings in the western end of the north aisle in the Hagia Sophia revealed a rectangular space delineated by curtain rings. The SE corner of the church was assigned to forty deaconesses. An analysis of the music sources in which the texts are fully written out suggests that the deaconesses took part in the procession of the Great Entrance ceremony at the beginning of the Mass of the Faithful as well in rituals in front of the ambo. ……………………………………………………………………………………….. Since the turn of the century, a lively discussion has developed about the function and place of deaconesses in the Greek and Russian Orthodox Churches. In her 2002 dissertation on "The Liturgical Participation of Women in the Byzantine Church.”1 Valerie Karras examined the ordination rites for deaconesses preserved in eighth-century to eleventh-century euchologia. In the Novellae Constitutiones added to his code Justinian stipulated that there were to be forty deaconesses assigned to the Hagia Sophia:2 Wherefore We order that not more than sixty priests, a hundred deacons, forty deaconesses, ninety sub-deacons, a hundred and ten readers, or twenty-five choristers, shall be attached to the Most Holy Principal Church, so that the entire number of most reverend ecclesiastics belonging thereto shall not exceed four hundred and twenty in all, without including the hundred other members of the clergy who are called porters. -

Vespers Program Print 31MAR

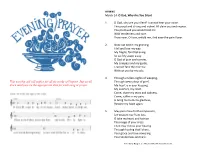

HYMNS March 24: O God, Why Are You Silent 1. O God, why are you silent? I cannot hear your voice. The proud and strong and violent All claim you and rejoice. You promised you would hold me With tenderness and care. Draw near, O Love, enfold me, And ease the pain I bear. 2. Now lost within my grieving, I fall and lose my way. My fragile, faint believing So swiftly swept away. O God of pain and sorrow, My compass and my guide, I cannot face the morrow Without you by my side. 4. Through endless nights of weeping, This worship aid will suffice for all six weeks of Vespers. Just scroll Through weary days of grief, down until you see the appropriate date for each song or prayer. My heart is in your keeping, My comfort, my relief. Come, share my tears and sadness, Come, suffer in my pain; O bring me home to gladness, Restore my hope again. 5. May pain draw forth compassion, Let wisdom rise from loss. O take my heart and fashion The image of your cross. Then may I know your healing Through healing that I share, Your grace and love revealing Your tenderness and care. Text: Marty Haugen, b. 1950, © 2003, GIA Publications, Inc. EVENING THANKSGIVING PSALMS Each night, we begin with Psalm 141, and incense is placed in the censer to suggest our prayers rising to God. At the end of this and each psalm, there is a prayer by the presider. Every night: Psalm 141 Evening Offering March 31: Psalm 23 Shepherd Me, O God READING MAGNIFICAT (next page) INTERCESSIONS THE LORD’S PRAYER CLOSING PRAYER Presider: Our help is in the name of the Lord. -

Quality Silversmiths Since 1939. SPAIN

Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com - ARTIMETAL - PROCESSIONALIA 2014-2015 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN ARTISTIC SILVER INDEXINDEX Presentation ......................................................................................... Pag. 1-12 ARTISTIC SILVER - ARTIMETAL ARTISTICPresentation SILVER & ARTIMETAL Pag. 1-12 ChalicesChalices && CiboriaCiboria ........................................................................... Pag. 13-6713-52 MonstrancesCruet Sets & Ostensoria ...................................................... Pag. 68-7853 TabernaclesJug & Basin,........................................................................................... Buckets Pag. 79-9654 AltarMonstrances accessories & Ostensoria Pag. 55-63 &Professional Bishop’s appointments Crosses ......................................................... Pag. 97-12264 Tabernacles Pag. 65-80 PROCESIONALIAAltar accessories ............................................................................. Pag. 123-128 & Bishop’s appointments Pag. 81-99 General Information ...................................................................... Pag. 129-132 ARTIMETAL Chalices & Ciboria Pag. 101-115 Monstrances Pag. 116-117 Tabernacles Pag. 118-119 Altar accessories Pag. 120-124 PROCESIONALIA Pag. 125-130 General Information Pag. 131-134 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. Justo Dorado, 12 28040 Madrid, Spain Product design: Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. CHALICES & CIBORIA Our silversmiths combine -

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents

Founded 1866 The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Monday: Miraculous Medal Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Therese Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) 8:00 a.m. (Tridentine Latin only during Lent) 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Devotions and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Vespers and Benediction: Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Saturday at 12:35 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. 10:30 a.m. -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

KURIAKOSE ELIAS CHAVARA the Wise Liturgical Reformer of Thomas Christians of Malabar

Theological Studies on Saint Chavara 5 KURIAKOSE ELIAS CHAVARA The Wise Liturgical Reformer of Thomas Christians of Malabar Dharmaram Publications No. 456 Theological Studies on Saint Chavara 5 KURIAKOSE ELIAS CHAVARA The Wise Liturgical Reformer of Thomas Christians of Malabar Francis Kanichikattil CMI 2020 Chavara Central Secretariat Kochi 680 030 Kerala, India & Dharmaram Publications Bangalore 560029 India Kuriakose Elias Chavara: The Wise Liturgical Reformer of Thomas Christians of Malabar Francis Kanichikattil CMI Email: ffkanichikattil @gmail.com © 2020: Saint Chavara’s 150th Death Anniversary Edition Chavara Central Secretariat, Kochi Cover: Thomson P. J. & David, Smriti, Thrissur Image: Dharmaram College Chapel, Bangalore Layout: Chavara Central Secretariat, Kochi Printing: Viani Printers, Kochi ISBN: 978-81-944061-3-6 Price: Rs. 140; US$ 15 Chavara Central Secretariat CMI Prior General’s House Chavara Hills, Kakkanad Post Box 3105, Kochi 682 030 Kerala, India Tel: +91 484 2881802/3 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.chavaralibrary.in/ & Dharmaram Publications Dharmaram College, Bangalore 560029, India Tel: +91-8041116137; 6111 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Web: www.dharmarampublications.com CONTENTS Theological Studies on Saint Chavara vii Preface ix Introduction 1 PART 1 Chapter 1 23 Liturgical Contributions of Saint Kuriakose Elias Chavara Chapter 2 35 Saint Kuriakose Elias Chavara: A Wise Liturgical Reformer of the Thomas Christians of Malabar PART 2 A. Thukasa: ‘Order’ of Eucharistic Liturgy Chapter 3 53 Priest’s Preparation before Celebrating the Holy Kurbana Chapter 4 65 Ceremonies of the Holy Kurbana from the Beginning till the End of Gospel Reading Chapter 5 75 Ceremonies of the Holy Kurbana from Preparation of the Offertory till the Anaphora Prayer Chapter 6 85 Ceremonies of the Holy Kurbana: The Anaphora of Mar Addai and Mari v vi Chavara: The Wise Liturgical Reformer Chapter 7 105 The Consecration of Bread and Wine: Fraction, Consignation, Holy Communion, and Concluding Prayers B. -

The Rites of Holy Week

THE RITES OF HOLY WEEK • CEREMONIES • PREPARATIONS • MUSIC • COMMENTARY By FREDERICK R. McMANUS Priest of the Archdiocese of Boston 1956 SAINT ANTHONY GUILD PRESS PATERSON, NEW JERSEY Copyright, 1956, by Frederick R. McManus Nihil obstat ALFRED R. JULIEN, J.C. D. Censor Lib1·or111n Imprimatur t RICHARD J. CUSHING A1·chbishop of Boston Boston, February 16, 1956 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA INTRODUCTION ANCTITY is the purpose of the "new Holy Week." The news S accounts have been concerned with the radical changes, the upset of traditional practices, and the technical details of the re stored Holy Week services, but the real issue in the reform is the development of true holiness in the members of Christ's Church. This is the expectation of Pope Pius XII, as expressed personally by him. It is insisted upon repeatedly in the official language of the new laws - the goal is simple: that the faithful may take part in the most sacred week of the year "more easily, more devoutly, and more fruitfully." Certainly the changes now commanded ,by the Apostolic See are extraordinary, particularly since they come after nearly four centuries of little liturgical development. This is especially true of the different times set for the principal services. On Holy Thursday the solemn evening Mass now becomes a clearer and more evident memorial of the Last Supper of the Lord on the night before He suffered. On Good Friday, when Holy Mass is not offered, the liturgical service is placed at three o'clock in the afternoon, or later, since three o'clock is the "ninth hour" of the Gospel accounts of our Lord's Crucifixion. -

Imge A&Ea Dem Bepaa® Dbs P&Mareaats Mattaabs' I, Voa Kanflftaaimopat, By3, 37, 1987 (1S88), 417=418

Durham E-Theses Matthew I, Patriarch of Constantinople (1397 - 1410), his life, his patriarchal acts, his written works Kapsalis, Athanasius G. How to cite: Kapsalis, Athanasius G. (1994) Matthew I, Patriarch of Constantinople (1397 - 1410), his life, his patriarchal acts, his written works, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5836/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 MATTHEW I, PATRIARCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE (1397 - 1410), HIS LIFE, HIS PATRIARCHAL ACTS, HIS WRITTEN WORK: The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. MASTER OF ARTS THESIS, SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM 1994 A 4} nov m This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research or private study on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement.' =1= CONTENTS ABSTRACT XV-V LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS VX-VIII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS DC NOTES ON PROPER NAMES X GENERAL INTRODUCTION A brief Historical, Political and Eccle• siastical description of Byzantium during the XTV century and the beginning of the XV.