Satellite Investigation of Tropical Cirrus Lifecycle and Relation to Water Vapor and Deep Convection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contrail-Cirrus and Their Potential for Regional Climate Change

Contrail-Cirrus and Their Potential for Regional Climate Change Kenneth Sassen Department of Meteorology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah ABSTRACT After reviewing the indirect evidence for the regional climatic impact of contrail-generated cirrus clouds (contrail- cirrus), the author presents a variety of new measurements indicating the nature and scope of the problem. The assess- ment concentrates on polarization lidar and radiometric observations of persisting contrails from Salt Lake City, Utah, where an extended Project First ISCCP (International Satellite Cloud Climatology Program) Regional Experiment (FIRE) cirrus cloud dataset from the Facility for Atmospheric Remote Sensing has captured new information in a geographical area previously identified as being affected by relatively heavy air traffic. The following contrail properties are consid- ered: hourly and monthly frequency of occurrence; height, temperature, and relative humidity statistics; visible and in- frared radiative impacts; and microphysical content evaluated from in situ data and contrail optical phenomenon such as halos and coronas. Also presented are high-resolution lidar images of contrails from the recent SUCCESS experiment, and the results of an initial attempt to numerically simulate the radiative effects of an observed contrail. The evidence indicates that the direct radiative effects of contrails display the potential for regional climate change at many midlati- tude locations, even though the sign of the climatic impact may be uncertain. However, new information suggests that the unusually small particles typical of many persisting contrails may favor the albedo cooling over the greenhouse warming effect, depending on such factors as the geographic distribution and patterns in day versus night aircraft usage. -

Direccion De Personal Aeronautico Dpto. De

DIRECCION DE PERSONAL AERONAUTICO 26/09/2021 MTC DPTO. DE INSTRUCCION OGMS/DINF PREGUNTAS Y OPCIONES POR TEMA 14:03 Pag: 1 TEMA: 0626 ATP-RTC - Meteorology and Weather Services - Chap.8 COD_PREG: PREGUNTA: RPTA: PREG20098166 What is indicated on the Weather Depiction Chart by a continuous smooth C (9299) line enclosing a hatched geographic area? OPCION A: The entire area has ceilings less than 1,000 feet and/or visibility less than 3 miles OPCION B: More than 50 percent of the area enclosed by the smooth line is predicted to have IFR conditions OPCION C: Reporting stations within the enclosed area are all showing IFR conditions at the time of the report OPCION D: PREG20098167 The horizontal wind shear, critical for turbulence (moderate or greater) per B (9701) 150 miles is OPCION A: 18 knots or less OPCION B: greater than 18 knots OPCION C: not a factor, only vertical shear is a factor OPCION D: PREG20098168 A severe thunderstorm is one in which he surface wind is A (9706) OPCION A: 50 knots or greater and/or surface hail is 3/4 inch or more in diameter. OPCION B: 55 knots or greater and/or surface hail is 1/2 inch or more in diameter. OPCION C: 45 knots or greater and/or surface hail is 1 inch or more in diameter. OPCION D: PREG20098169 A squall is a sudden increase of at least 16 knots in average wind speed to a B (9708) sustained speed of OPCION A: 24 knots or more for at least 1 minute OPCION B: 22 knots or more for at least 1 minute OPCION C: 20 knots or more for at least 1 minute OPCION D: PREG20098170 A calm wind that is forecast, in the international Terminal Aerodrome B (9709) Forecast (TAF) is encoded as OPCION A: VRB00KT OPCION B: 00000KT OPCION C: 00003KT OPCION D: PREG20098171 In the International Terminal Aerodrome Forecast (TAF), a variable wind C (9710) direction is noted by "VRB" where the three digit direction usually appears. -

International Atlas of Clouds and of States of the Sky

INTERNATIONAL METEOROLOGICAL COMMITTEE COMMISSION FOR THE STUDY OF CLOUDS International Atlas of Clouds and of States of the Sky ABRIDGED EDITION FOR THE USE OF OBSERVERS PARIS Office National Meteorologique, Rue de I'Universite, 176 193O International Atlas of Clouds and of States of the Sky THIS WORK FOR THE USE OF OBSERVERS CONSISTS OF : 1. This volume of text. 2. An album of 41 plates. It is an abreviation of the complete work : The International Atlas of Clouds and of States of the Sky. It is published thanks to the generosity of The Paxtot Institute of Catalonia. INTERNATIONAL METEOROLOGICAL COMMITTEE COMMISSION FOR THE STUDY OF CLOUDS International Atlas of Clouds and of States of the Sky ABRIDGED EDITION FOR THE USE OF OBSERVERS Kon. Nad. Metoor. Intl. De Bilt PARIS Office National Meteorologique. Rue de I'Universite. 176 193O In memory of our Friend A. DE QUERVAIN Member of the International Commluion for the Study of Cloudt INTRODUCTION Since 1922 the International Commission for the Study of Clouds has been engaged in studying the classification of clouds for a new International Atlas. The complete work will appear shortly, and in it will be found a history of the undertaking. This atlas is only a summary of the complete work, and is intended for the use of observers. The necessity for it was realised by the Inter- national Conference of Directors, in order to elucidate the new inter- national cloud code; this is based on the idea of the state of the sky, but observers should be able to use it without difficulty for the separate analysis of low, middle, and high clouds. -

Regional Codes and National Coding Practices, Volume II

Manual on Codes Regional Codes and National Coding Practices Volume II 2011 edition Updated in 2018 WEATHER CLIMATE WATER CLIMATE WEATHER WMO-No. 306 Manual on Codes Regional Codes and National Coding Practices Volume II 2011 edition Updated in 2018 WEATHER CLIMATE WATER CLIMATE WEATHER WMO-No. 306 WMO-No. 306 © World Meteorological Organization, 2011 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chair, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 81 17 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Email: [email protected] ISBN 978-92-63-10306-2 NOTE The designations employed in WMO publications and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the WMO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WMO in preference to others of a similar nature which are not mentioned or advertised. PUBLICATION REVISION TRACK RECORD Purpose of Date Part/chapter/section -

Guide to Surface Weather Observations

Antigua and Barbuda Meteorological Services Guide to Surface Weather Observations First Edition August 2018 First Edition, August 2018 Forward The contents of this guide prescribes the standard procedures of the Antigua and Barbuda Meteorological Services (ABMS) for observing, recording and reporting weather conditions. It has been prepared in accordance with internationally recommended procedures as established by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). The practices and procedures in this document apply to all ABMS observering personnel who provide weather observation services. Weather observer personnel are required to apply the provision of this guide as it pertains to their observational responsibilities. Observers are expected to exercise experienced judgment when encountering situations not covered by this guide. This is a living document and will be revised at intervals to take account of changes in regulations, feedback from the industry and recognised best practices. Inquiries on the content of this guide should be directed to the management of the ABMS through appropriate channels. Guide to Surface Weather Observations Page | 1 First Edition, August 2018 Record of Revisions Section Revision description Guide to Surface Weather Observations Page | 2 First Edition, August 2018 Record of Amendments This document will be kept under continual review to ensure its relevance to the Quality Management System Amendments No. Date Entered Entered by Approved August 2018, initial -

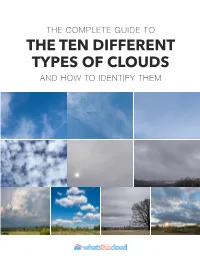

The Ten Different Types of Clouds

THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE TEN DIFFERENT TYPES OF CLOUDS AND HOW TO IDENTIFY THEM Dedicated to those who are passionately curious, keep their heads in the clouds, and keep their eyes on the skies. And to Luke Howard, the father of cloud classification. 4 Infographic 5 Introduction 12 Cirrus 18 Cirrocumulus 25 Cirrostratus 31 Altocumulus 38 Altostratus 45 Nimbostratus TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 51 Cumulonimbus 57 Cumulus 64 Stratus 71 Stratocumulus 79 Our Mission 80 Extras Cloud Types: An Infographic 4 An Introduction to the 10 Different An Introduction to the 10 Different Types of Clouds Types of Clouds ⛅ Clouds are the equivalent of an ever-evolving painting in the sky. They have the ability to make for magnificent sunrises and spectacular sunsets. We’re surrounded by clouds almost every day of our lives. Let’s take the time and learn a little bit more about them! The following information is presented to you as a comprehensive guide to the ten different types of clouds and how to idenify them. Let’s just say it’s an instruction manual to the sky. Here you’ll learn about the ten different cloud types: their characteristics, how they differentiate from the other cloud types, and much more. So three cheers to you for starting on your cloud identification journey. Happy cloudspotting, friends! The Three High Level Clouds Cirrus (Ci) Cirrocumulus (Cc) Cirrostratus (Cs) High, wispy streaks High-altitude cloudlets Pale, veil-like layer High-altitude, thin, and wispy cloud High-altitude, thin, and wispy cloud streaks made of ice crystals streaks -

Observation of Clouds

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00556-3 - Physics and Dynamics of Clouds and Precipitation Pao K. Wang Excerpt More information 1 Observation of clouds 1.1 Water vapor in the atmosphere The clouds in our atmosphere are a condensed form of water (water droplets and ice particles) suspended in air. Such a system is called an aerosol. Naturally, the necessary constituent in air for forming clouds is water vapor. Thus it is important for us to understand the general situation of water vapor in our atmosphere. Water vapor is so pervasive in our daily life that many do not know that its concentration is actually quite small. Table 1.1 lists the five major gaseous consti- tuents and their volume concentrations in the Earth’s atmosphere. Water vapor ranks fourth after N2,O2, and Ar. Water vapor is also different from the other four gases in another important aspect: whereas the concentrations of N2,O2, Ar, and CO2 remain fairly constant from place to place, the concentration of H2O is highly variable. The layer imme- diately above the warm tropical ocean surface is literally steaming with water vapor; the highest value is ~ 4% (tropical Indian Ocean), whereas the surface layer over the Sahara Desert in North Africa or the Taklimakan Desert in western China is close to 0%. Thus, even though the water vapor concentration in the whole atmosphere is more than that of CO2, as shown in Table 1.1, there are places in the world where its concentration is less than that of CO2. Water vapor concentration also varies with height. -

High-Altitude Cirrus Clouds and Climate

GENERAL I ARTICLE High-Altitude Cirrus Clouds and Climate S Veerabuthiran Introduction Clouds are aesthetically appealing. Without them, there would be no rain or snow, thunder or lightning, rainbows or halos. A cloud is a visible aggregate of tiny water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air. Most clouds result from cooling due to lifting of moisture containing air. Those associated with strong rising air currents have vertical development and a puffy appear ance, whereas those resulting from gentler lifting or other meth ods of cooling tend to spread out into layers. Although their method of formation is largely responsible for their appearance, S Veerabuthiran is a clouds are classified primarily on the basis of their altitude, research fellow in Space Physics Laboratory, shape, color, and transmission or reflection of light. Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, Trivandrum. His Classification of Clouds research involves the study of aerosols, dusts The French naturalist Lamarck (1744-1829) proposed a system and clouds in the lower for classifying clouds in 1802. This work however, did not atmosphere and tempera receive wide acclaim. One year later Luke Howard, an English ture structure in the upper naturalist, developed a clouds classification system that found atmosphere. general acceptance. He named sheet-like clouds as stratus (Latin for layers); puffy clouds as cumulus (heap); wispy clouds as cirrus (curl of hair); and rain clouds as nimbus (violent rain). These are the four basic forms of clouds. Other clouds can be described by combination of these basic types. For example, nimbostratus is a rain cloud that shows layering, whereas cumulonimbus is a rain cloud having pronounced vertical development. -

Water in the Atmosphere 97

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Caption goes here © Jonesand can & several Bartlett lines Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOTlong FOR as shownSALE here. OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Caption goes here and can several lines long as shown here. Caption goes here and can several lines long as shown here. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC 4NOT FOR SALEWater OR DISTRIBUTION in the AtmosphereNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHHAPTTEER OUUTLLININE INTRODUCTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOTEVAPORATION: FOR SALE OR THE DISTRIBUTION SOURCE OF ATMOSPHERICNOT WATER FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION MEASURING WATER VAPOR IN THE AIR ■ Mixing Ratio ■ Vapor Pressure © Jones & Bartlett■ Relative Learning, Humidity LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE■ ORDew DISTRIBUTION Point/Frost Point NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CONDENSATION AND DEPOSITION: CLOUD FORMATION ■ Solute and Curvature -

The Kiwi Kids Cloud Identification Guide

Droplets The Kiwi Kids Cloud Identification Guide Written by Paula McKean Droplets The Kiwi Kids Cloud Identification Guide ISBN 1-877264-27-X Paula McKean MEd Hons (Science Ed), BEd, DipTchg 2009 © Crown Copyright 2009 Contents 1. Cloud Classification 2. How Clouds are formed 3. The Water Cycle 4. Cumulus Altitudes 5. Stratus Altitudes 6. Precipitating Cloud Altitudes 7. Cirrus Cloud Altitudes 8. Cumulus 10. Altocumulus 12. Cirrocumulus 14. Stratus 16. Stratocumulus 18. Altostratus 20. Cirrostratus 22. Nimbostratus 24. Cumulus Congestus 26. Cumulonimbus 28. Cirrus 30. Contrails 32. References 33. Acknowledgements Cloud Classification Since Luke Howard developed the first cloud classification system in 1802, clouds have been classified according to the altitude of the cloud base and the shape of the cloud. There are three main categories: Low level- Clouds that form below 2000 m: Cumulus, Stratocumulus, Stratus (including Fog, Haze and Mist), Nimbostratus and Cumulonimbus. Mid level - Clouds that form between 2000 m and 7000 m: Altocumulus and Altostratus. High level - Clouds that form above 5000 m: Cirrus, Cirrocumulus, Cirrostratus and Contrails. In this guide cloud types have been organised by their characteristics so it is easier to distinguish between clouds that appear to be similar and to help determine the cloud type when the altitude can’t be determined. Clouds have been grouped into four categories: • Cumulus (heaped, puffy appearing clouds). • Stratus (flat clouds that extend over large sections of sky). • Precipitating (clouds that can produce rain, hail or snow). • Cirrus (wispy high altitude clouds). By using a combination of the altitude system and characteristic based system used in this guide, cloud identification will be easier and more accurate. -

Water in the Atmosphere

10892_04_ch4_p82-125.qxd 2/3/06 1:43 PM Page 82 CHAPTER 4 Water in the Atmosphere Evaporation: The Source of Atmospheric Water Measuring Water Vapor in the Air Mixing Ratio Vapor Pressure Relative Humidity Box 4.1: Atmospheric Moisture and Your Health Dew Point/Frost Point Condensation and Deposition: Cloud Formation Solute and Curvature Effects Nucleation Cloud Particle Growth by Condensation and Deposition Fog Formation Lifting Mechanisms That Form Clouds Static Stability and Cloud Development The Saturated Adiabatic Lapse Rate Conditionally Unstable Environments Cloud Classification Low Clouds Precipitating Clouds Middle Clouds High Clouds Clouds and the Greenhouse Effect Cloud Composition Precipitation Precipitation Growth in Warm Clouds Box 4.2: Controlling the Weather Collision-Coalescence Precipitation Growth in Cold Clouds Precipitation Types Clouds, Lapse Rates, and Precipitation Near Mountains 10892_04_ch4_p82-125.qxd 2/3/06 1:43 PM Page 83 After completing this chapter, you should be able to: • Define saturation and its importance in the atmosphere • Explain why there can be more water vapor in warm air than cold air and how this affects the atmosphere • Describe how clouds and precipitation form • Identify the major cloud and precipitation types and explain the significant differences among them Introduction In early January 1998, the Canadian province of Quebec was literally crushed by water falling from the sky. For a solid week, water vapor slid upward over the northeastern United States and central and eastern Canada. The vapor turned to clouds (yellow and orange areas in satellite pic- ture), and precipitation dropped out of the clouds. Rain fell on Quebec, but the temperatures at the ground were cold enough for the rain to freeze on contact with roofs, roads, trees, and towers. -

On the Regional Climatic Impact of Contrails: Microphysical and Radiative Properties of Contrails and Natural Cirrus Clouds B

Ann. Geophysicae 15, 1457±1467 (1997) Ó EGS ± Springer-Verlag 1997 On the regional climatic impact of contrails: microphysical and radiative properties of contrails and natural cirrus clouds B. Strauss1, R. Meerkoetter 1, B. Wissinger1, P. Wendling1, M. Hess2 1Deutsche Forschungsanstalt fuer Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR), Institut fuer Physik der Atmosphaere, Oberpfaenhofen, D-82234 Wessling, Germany 2Meteorologisches Institut der Universitaet Muenchen, Muenchen, Germany Received: 17 November 1995 / Revised: 12 May 1997 / Accepted: 6 June 1997 Abstract. The impact of contrail-induced cirrus clouds Therefore, the impact of contrails, or better `air-trac- on regional climate is estimated for mean atmospheric induced cirrus clouds' was discussed recently within the conditions of southern Germany in the months of July scope of air trac and climate in general (Schumann, and October. This is done by use of a regionalized one- 1994). Liou et al. (1990) studied the global in¯uence of dimensional radiative convective model (RCM). The contrails within a case-study, using a two-dimensional in¯uence of an increased ice cloud cover is studied by climate model. They found an increase in surface comparing RCM results representing climatological temperature of 1 K in the case of an increase in cloud values with a modi®ed case. In order to study the cover by 5% between 20 and 70N. Ponater et al. sensitivity of this eect on the radiative characteristics of (1996) studied the in¯uence of an increase in water the ice cloud, two types of additional ice clouds were vapour and in cirrus cloud cover induced by air trac modelled: cirrus and contrails, the latter cloud type using a three-dimensional GCM.