S/2015/852 Security Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Download the COI Focus

OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER GENERAL FOR REFUGEES AND STATELESS PERSONS PERSONS COI Focus IRAQ Security Situation in Central and Southern Iraq 20 March 2020 (update) Cedoca Original language: Dutch DISCLAIMER: This COI-product has been written by Cedoca, the Documentation and Research Department of the CGRS, and it provides information for the processing of applications for international protection. The document does not contain policy guidelines or opinions and does not pass judgment on the merits of the application for international protection. It follows the Common EU Guidelines for processing country of origin information (April 2008) and is written in accordance with the statutory legal provisions. The author has based the text on a wide range of public information selected with care and with a permanent concern for crosschecking sources. Even though the document tries to cover all the relevant aspects of the subject, the text is not necessarily exhaustive. If certain events, people or organizations are not mentioned, this does not mean that they did not exist. All the sources used are briefly mentioned in a footnote and described in detail in a bibliography at the end of the document. Sources which have been consulted but which were not used are listed as consulted sources. In exceptional cases, sources are not mentioned by name. When specific information from this document is used, the user is asked to quote the source mentioned in the bibliography. This document can only be published or distributed with the written consent of the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons. TO A MORE INTEGRATED MIGRATION POLICY, THANKS TO AMIF Rue Ernest Blerot 39, 1070 BRUSSELS T 02 205 51 11 F 02 205 50 01 [email protected] www.cgrs.be IRAQ. -

International Protection Considerations with Regard to People Fleeing the Republic of Iraq

International Protection Considerations with Regard to People Fleeing the Republic of Iraq HCR/PC/ May 2019 HCR/PC/IRQ/2019/05 _Rev.2. INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION CONSIDERATIONS WITH REGARD TO PEOPLE FLEEING THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .......................................................................................... 6 1) Refugee Protection under the 1951 Convention Criteria and Main Categories of Claim .... 6 2) Broader UNHCR Mandate Criteria, Regional Instruments and Complementary Forms of Protection ............................................................................................................................. 7 3) Internal Flight or Relocation Alternative (IFA/IRA) .............................................................. 7 4) Exclusion Considerations .................................................................................................... 8 5) Position on Forced Returns ................................................................................................. 9 II. Main Developments in Iraq since 2017 ............................................................. 9 A. Political Developments ........................................................................................................... 9 1) May 2018 Parliamentary Elections ...................................................................................... 9 2) September 2018 Kurdistan Parliamentary Elections ......................................................... 10 3) October 2017 Independence -

ISIS in Iraq

i n s t i t u t e f o r i n t e g r at e d t r a n s i t i o n s The Limits of Punishment Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism iraq case study Mara Redlich Revkin May, 2018 After the Islamic State: Balancing Accountability and Reconciliation in Iraq About the Author Mara Redlich Revkin is a Ph.D. Candidate in Acknowledgements Political Science at Yale University and an Islamic The author thanks Elisabeth Wood, Oona Law & Civilization Research Fellow at Yale Law Hathaway, Ellen Lust, Jason Lyall, and Kristen School, from which she received her J.D. Her Kao for guidance on field research and survey research examines state-building, lawmaking, implementation; Mark Freeman, Siobhan O’Neil, and governance by armed groups with a current and Cale Salih for comments on an earlier focus on the case of the Islamic State. During draft; and Halan Ibrahim for excellent research the 2017-2018 academic year, she will be col- assistance in Iraq. lecting data for her dissertation in Turkey and Iraq supported by the U.S. Institute for Peace as Cover image a Jennings Randolph Peace Scholar. Mara is a iraq. Baghdad. 2016. The aftermath of an ISIS member of the New York State Bar Association bombing in the predominantly Shia neighborhood and is also working on research projects concern- of Karada in central Baghdad. © Paolo Pellegrin/ ing the legal status of civilians who have lived in Magnum Photos with support from the Pulitzer areas controlled and governed by terrorist groups. -

“Barriers to Post-ISIS Reconciliation in Iraq: Case Study of Tel Afar, Ninewa” by Sarah Sanbar Under the Supervision of Prof

“Barriers to post-ISIS reconciliation in Iraq: Case study of Tel Afar, Ninewa” By Sarah Sanbar Under the supervision of Professor Stéphane Lacroix Sciences Po Spring 2020 This paper has received the Kuwait Program at Sciences Po Student Paper Award The copyright of this paper remains the property of its author. No part of the content may be reproduced, published, distributed, copied or stored for public or private use without written permission of the author. All authorisation requests should be sent to [email protected] BARRIERS TO POST-ISIS RECONCILIATION IN IRAQ Case Study of Tel Afar, Ninewa Instructor: Stéphane LACROIX Final Assignment: The Political Sociology of the State in the Contemporary Arab World Date: 30/04/2020 Sarah Sanbar Sanbar - 1 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Literature Review ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Case Study: Tel Afar, Ninewa .................................................................................................................... 5 Context and Demographics ....................................................................................................................... 5 ISIS Occupation, Displacement, and the Liberation Operation ................................................................ 6 Barriers to Post-ISIS Reconciliation in Tel -

The Islamic State Effect on Minorities in Iraq

Review of Arts and Humanities June 2015, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 7-11 ISSN: 2334-2927 (Print), 2334-2935 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/rah.v4n1a2 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/rah.v4n1a2 The Islamic State Effect on Minorities in Iraq Dr. Shak Hanish1 Abstract Since the control of “the Islamic state in Iraq and Syria” (ISIS) over large parts of Iraq, especially in the north, ethnic and religious minorities living there are facing several problems and challenges, including the issue of survival. In this paper, I will examine the impact of ISIS on these religious and ethnic minorities in Iraq and the problems they encounter. I will suggest some ways to help them withstand pressure and stay in their original homeland of Iraq, especially in Nineveh province, where most of these minorities of Christians, Yazedis, Shabaks, and Turkomans live. Keywords: The Middle East; Ethnic and Minority Issues; Human Rights; Religious Minorities Introduction Iraq is one of the important countries in the Middle East that includes several religious, ethnic, and national minorities that have lived there, some for thousands of years. Many are considered the indigenous people of Mesopotamia. They are the Chaldeans-Assyrians-Syriacs, the Yazidis, the Sabeans Mandaeans, the Shabaks, the Turkomans, and formerly the Jews. Their presence in Iraq dates back hundreds of years, some before the advent of Islam. They live in northern, central, and southern Iraq. Today, most of them live near the Kurdistan region of Iraq (Tayyar, 2014). -

Weekly Explosive Incidents Flash News

iMMAP - Humanitarian Access Response Weekly Explosive Hazard Incidents Flash News (14 - 20 January 2021) 93 139 17 40 1 INCIDENTS PEOPLE KILLED PEOPLE INJURED EXPLOSIONS AIRSTRIKE ANBAR GOVERNORATE ISIS 17/JAN/2021 Detonated an IED killing a civilian and eight soldiers, including an officer in Al-Shara Security Forces 14/JAN/2021 village of Sinjar district. Found and cleared three IEDs in Falluja district. Security Forces 17/JAN/2021 ISIS 15/JAN/2021 Found a mass grave of 14 civilians in Al-Hajir valley. Detonated an IED and injured eight members of the Popular Mobilization Forces near Akashat area of Kaim district. An Armed Group 19/JAN/2021 Iraqi Military Forces 16/JAN/2021 Detonated an IED injuring three civilians in Al-Haj village of Al-Qayyarah sub-district. Launched an airstrike destroying an ISIS hideout and killing two ISIS insurgents in Dhira Dijla area of al-Karma sub-district. Military Intelligence 20/JAN/2021 Found and cleared five IEDs belonging to ISIS in al-Rambusy al-Sharqi area, west ISIS 17/JAN/2021 Ninewa. Killed a civilian and injured another by a landmine explosion in Haditha district. Security Forces 20/JAN/2021 DIYALA GOVERNORATE Found and cleared an ISIS hideout in the western Anbar desert towards the Rutba district. ISIS 15/JAN/2021 Attacked Al-Shahada area in Jalula sub-district of Baqubah district, killing a police Coalition Forces 20/JAN/2021 member and injuring three civilians. Found and cleared two IEDs in Wadi Huran area. Security Forces 18/JAN/2021 Coalition Forces 20/JAN/2021 Found the corpse of a civilian in Baqubah district. -

Iraq: Security and Humanitarian Situation

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Security and humanitarian situation Version 6.0 May 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

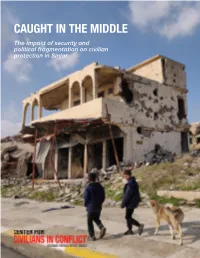

Caught in the Middle: the Impact of Security

CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE The impact of security and political fragmentation on civilian protection in Sinjar civiliansinconflict.org i RECOGNIZE. PREVENT. PROTECT. AMEND. PROTECT. PREVENT. RECOGNIZE. Cover: Children walking among the October 2020 rubble in Sinjar, February 2020. Credit: CIVIC/Paula Garcia T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] civiliansinconflict.org Table of Contents About Center for Civilians in Conflict .................................v Acknowledgments .................................................v Glossary .........................................................vi Executive Summary ................................................1 Recommendations .................................................4 Methodology .................................................... 6 Background .......................................................7 Sinjar’s Demographics ............................................10 Protection Concerns .............................................. 11 Barriers to Return ............................................... 11 Sunni Arabs Prevented from Returning ............................15 Lack of Government Services Impacting Rights ....................18 Security Actors’ Behavior and Impact on Civilians .................22 Civilian Harm from Turkish Airstrikes ............................. 27 Civilian Harm from ERW and IED Contamination ..................28 Delays in Accessing Compensation ..............................31 Reconciliation and Justice Challenges ...........................32 -

February 2019.Pdf

IRAQ PROTECTION UPDATE – FEBRUARY 2019 Affected Highlights Population . Approximately 1,300 families across Iraq departed from camps and 1,100 families arrived in camps in February 2019. 297,595 Refugees and . Eight camps were closed in February resulting in secondary Asylum-Seekers displacement and premature returns. (as of 28 February 2019) . Families with perceived affiliation with extremists continue to face collective punishment in the form of restrictions on their freedom of 1,744,980 Internally movement, denial of return, and refusal of civil documentation. Displaced Persons (IDPs) . UNHCR and partners supported government’s mobile missions to issue marriage and birth certificates to IDPs in East Mosul camps, and 4,211,982 Returnees assisted 593 IDPs in obtaining civil documentation. (as of 28 February 2019) Security Incidents Security incidents and military operations were reported throughout the month in Ninewa, Anbar, Diyala, Kirkuk, and Salah-Al-Din Governorates. In Anbar Governorate, multiple incidents were reported where extremists abducted and killed people who were collecting truffles in the deserts of 62,209 families reached* Haditha, Rutba and Rawa. Collecting truffles has been a main source of income for some returnees due to lack of livelihood opportunities. In Diyala Governorate, several attacks driven by a mix of extremist activities, sectarian violence and local disputes were reported. Insurgent 50,300 53,601 75,305 63,086 *The disaggregated figures indicate the cells launched attacks in the northern areas around Khanaqin and Lake number of households containing Hamrin, targeting civilians and security forces in an ongoing effort to individuals from each age and gender undermine the security situation. -

Weekly Explosive Incidents Flash News (02 - 08 APR 2020)

iMMAP - Humanitarian Access Response Weekly Explosive Incidents Flash News (02 - 08 APR 2020) 100 23 34 16 1 INCIDENTS PEOPLE KILLED PEOPLE INJURED EXPLOSIONS AIRSTRIKE DIYALA GOVERNORATE ISIS 03/APR/2020 Attacked a Military Forces checkpoint and injured two of their members in Rabe'ea Security Forces 02/APR/2020 subdistrict, 135km northwest of Mosul. Found and cleared 10 IEDs and materials for making IEDs inside ISIS hideouts in Mohammed Al-Aziz village and Zoor Al-Asyood village. Iraqi Military Forces 03/APR/2020 Repelled an ISIS attack, killing an ISIS member and arresting three others in Rabe'ea Popular Mobilization Forces 03/APR/2020 subdistrict, 135km northwest of Mosul. Repelled an ISIS attack in the Naft Khana area. ISIS 05/APR/2020 An Armed Group 03/APR/2020 An IED explosion killed a civilian and injured two others in Tal Afar district. A targeted IED explosion struck a Military Forces humvee killing a soldier and injuring two other soldiers and an officer in the outskirts of Al-Maadan village. ISIS 07/APR/2020 Shot and killed a civilian hours after his abduction in Sheikh Ibrahim village in An Armed Group 03/APR/2020 Al-Mahallabiya district, northwest of Mosul. An IED explosion injured two Popular Mobilization Forces members in the Naft Khana area, 89km northeast of Baqubah district. Federal Police Forces 07/APR/2020 Repelled an ISIS attack arresting two insurgents in Al-Namrood subdistrict, 40km An Armed Group 05/APR/2020 southeast of Mosul. An IED explosion injured two children in the Jalwla subdistrict in Khanaqin district. An Armed Group 08/APR/2020 Security Forces 05/APR/2020 An IED explosion struck a Federal Police Forces patrol vehicle injuring two members in Found and cleared a cache containing four IEDs, explosive materials, and AK-47s inside an Qabr Al-Abd village in Al-Shuree subdistrict, 40km south of Mosul. -

Review of the Civil Administration of Mesopotamia

» ipfji|iii|ii; D 3 § ii ' ^ UC-NRLF » !• ^ ^^ MESOPOTAMIA (REVIEW OF THE CIVIL ADMINISTRATION). o E E V I E W OF THE CIVIL ADMINISTRATION OF MESOPOTAMIA NOTE. This paper gives aa account of the civil administration of Mesopotamia during the British military occupation, that is to say, down to the summer of tlie present year, when, a Mandate for Mesopotamia having been accepted by Great Britain, steps were being taken for the early establishment of an Arab Government. His Majesty's Government caU-^d for a report on this difficult period from the Acting Civil Commissioner, who entrusted the preparation of it to Miss Gertrude L. BeU, C.B.E. India Office, 3rd December 1920. JUtttunWO to 6ot]& 3l?ou£irsi of Darliatnent ftp CTominanli of ?&t0 Mnie^tv, LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be pui-chased through any Bookseller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses : Imperial House, Kingsvvay, London, W.C. 2, and 1 28, Abingdon Street, London, S.W. ; Manchester .37, Peteb Street, ; Cardiff 1, St. Andrew's Crescjint, ; Edinburgh 23, Forth Street, ; or from E. PONSONBY, Ltd., 116, Grafton Street, Dublin. 1920. Price 2s. Net. [Cmd. 1061.] 11 ^sc,\\ K^ TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE. Chapter I. — Occupation of the Basrah Wilayat - - - 1 II.—Organisation of the Administration _ _ . 5 III.—The pacification of the Tribes and Relations with the Shi'ah towns up to the fail of Baghdad - - - 20 IV. -Relations with Arab and Kurdish Tribes, and with the Holy Cities after the fall of Baghdad - - - 33 — V.