The Discovery of the Iceman and a Series of Theories: a Review of the Literature Sara Tufts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity?

Special Volume 6 (2016): Space and Knowledge. Topoi Research Group Articles, ed. by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, pp. 777–818. Svend Hansen – Jürgen Renn – Florian Klimscha – Jochen Büttner – Barbara Helwing – Sebastian Kruse The Digital Atlas of Innovations: A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity Edited by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, Excellence Cluster Topoi, Berlin eTopoi ISSN 2192-2608 http://journal.topoi.org Except where otherwise noted, content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 Svend Hansen – Jürgen Renn – Florian Klimscha – Jochen Büttner – Barbara Helwing – Sebastian Kruse The Digital Atlas of Innovations: A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity The authors discuss the simultaneous appearance of technological innovations in three key technologies (metallurgy, wheeled vehicles, weighing systems) in the second half of the 4th millennium. This is done from a source-critical perspective because the innova- tions are discussed with the help of dynamic maps from the Topoi project Digital Atlas of Innovations. Besides indications of diffusion gradients influenced by special research conditions, exceptional waves of innovation can be detected for all three technologies in the discussed period. These waves of innovation cannot, however, be generalized but have to be understood on the basis of the respective technology traditions and lines of devel- opment specific to local areas. Monocentric diffusion theories can be clearly disproven, local technology developments and their converging in certain centrally situated regions have to be assumed instead. Similarly, the transfer of objects and their châine opératoire can only be detected rather infrequently, while the adaptation to local socio-economic and environmental factors can be demonstrated. -

Morphology of Modern Arrowhead Tips on Human Skin Analog*

J Forensic Sci, January 2018, Vol. 63, No. 1 doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13502 PAPER Available online at: onlinelibrary.wiley.com PATHOLOGY/BIOLOGY LokMan Sung,1,2 M.D.; Kilak Kesha,3 M.D.; Jeffrey Hudson,4,5 M.D.; Kelly Root,1 and Leigh Hlavaty,1,2 M.D. Morphology of Modern Arrowhead Tips on Human Skin Analog* ABSTRACT: Archery has experienced a recent resurgence in participation and has seen increases in archery range attendance and in chil- dren and young adults seeking archery lessons. Popular literature and movies prominently feature protagonists well versed in this form of weap- onry. Periodic homicide cases in the United States involving bows are reported, and despite this and the current interest in the field, there are no manuscripts published on a large series of arrow wounds. This experiment utilizes a broad selection of modern arrowheads to create wounds for comparison. While general appearances mimicked the arrowhead shape, details such as the presence of abrasions were greatly influenced by the design of the arrowhead tip. Additionally, in the absence of projectiles or available history, arrowhead injuries can mimic other instruments causing penetrating wounds. A published resource on arrowhead injuries would allow differentiation of causes of injury by forensic scientists. KEYWORDS: forensic science, forensic pathology, compound bow, arrow, broadhead, morphology Archery, defined as the art, practice, and skill of shooting arrows While investigations into the penetrating ability of arrows with a bow, is indelibly entwined in human history. Accounts of have been published (5), this article is the first large-scale study the bow and arrow can be chronicled throughout human civiliza- evaluating the cutaneous morphology of modern broadhead tion from its origins as a primary hunting tool, migration to utiliza- arrow tip injuries in a controlled environment. -

Museum of New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies

MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES THE GLOFUETA PROJECT: TEST EXCAVATIONS AT EIGHT PREHISTORIC SITESBETWEEN GLORIETA AND PECOS, NEW MEXICO Yvonne Roye Oakes with a contribution by James L. Moore Submitted by David A. Phillips, Jr., Ph.D. Principal Investigator ARCHAEOLOGY NOTES NO. 45 SANTA FE 1991 NEW MEXICO ADMINISTRATIVE SUMMARY In 1985 and 1986, the Research Section of the Laboratory of Anthropology, Museum of New Mexico, tested ten sites within the limits of the proposed reconstruction on State Road 50 between Glorieta and Pecos, New Mexico (New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department [NMSHTD] Project No. RS-1416[1]) and one site within the project limits at the Glorieta Interchange (NMSHTD Project No. IR-025-5[63]297). The purpose of the testing program was to evaluate the nature and extent of subsurface and surface remains on the sites and to determine their potential to yield significant information on the prehistory and history of the area. Project sites included two historic residential sites, a Pueblo fieldhouse, three rock shelters, and four lithic or sherd artifact scatters. One historic site, Pigeon’s Ranch (LA 49315), is on the National Register of Historic Places. It was the location of an 1850s stagestop on the Santa Fe Trail, a Civil War battle, and a trading post and tourist stop in the 1920s and 1930s. The other historic structure consists of a portion of a house foundation within the right-of-way. The two historic sites (LA 49265 and LA 49315) will be discussed in another volume. Remains of a small Pueblo IV fieldhouse were uncovered during the testing program. -

Jewellery, Watches, Antiquities and Objects of Vertu 17 March 2020 J15

DIX • NOONAN • WEBB JEWELLERY, WATCHES, ANTIQUITIES AND OBJECTS OF VERTU 17 MARCH 2020 J15 VERTU AND OBJECTS OF ANTIQUITIES WATCHES, WEBB JEWELLERY, • DIX • NOONAN www.dnw.co.uk 16 Bolton Street Mayfair London W1J 8BQ 020 7016 1700 [email protected] Jewellery, Watches, Antiquities and Objects of Vertu Tuesday 17th March 2020 at 1pm BOARD of DIRECTORS Pierce Noonan Chairman and CEO 020 7016 1700 [email protected] Nimrod Dix Deputy Chairman 020 7016 1820 [email protected] Robin Greville Chief Technology Officer 020 7016 1750 [email protected] Christopher Webb Head of Coin Department 020 7016 1801 [email protected] AUCTION and CLIENT SERVICES Philippa Healy Head of Administration (Associate Director) 020 7016 1775 [email protected] Emma Oxley Accounts and Viewing 020 7016 1701 [email protected] Christopher Mellor-Hill Head of Client Liaison (Associate Director) 020 7016 1771 [email protected] Chris Finch Hatton Client Liaison 020 7016 1754 [email protected] James King Head of Shipping and Facilities 020 7016 1833 [email protected] JEWELLERY, WATCHES and OBJECTS of VERTU Frances Noble Head of Department (Associate Director) 020 7016 1781 [email protected] Laura Smith Specialist 020 7016 1782 [email protected] Jessica Edmonds Junior Specialist and Auction Clerk 020 7016 1782 [email protected] COINS, TOKENS and COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS Christopher Webb Head of Department (Director) 020 7016 1801 [email protected] Peter Preston-Morley Specialist (Associate Director) 020 7016 1802 [email protected] Jim Brown Specialist 020 7016 1803 [email protected] Tim Wilkes Specialist -

Ötzi the Iceman Worksheets

From mummies to mitochondria, skeletons to sequencing, Denisovans to DNA, molecules to murder…. Our human Inheritance Understanding our genetic ancestry & what makes us human featuring Ötzi the iceman Look at the mummy! Did you know: The Making of Ötzi’s Replica What type of images were used to make Ötzi’s ancient tattoos were the 3D print of Ötzi? made by making fine cuts in his skin and then rubbing charcoal in the cuts. Where in Italy is the real mummy stored? Ancient Ink Ötzi has 57 visible tattoos in the form of small lines and crosses. (4 cannot be seen.) Fatal Wound FIND and DRAW as many tattoos as you can on the illustration of the iceman’s mummy Evidence suggests that Ötzi was shot by (each line counts as a single tattoo; a cross an arrow, and this caused his death. would count as two). MARK the location of the arrow wound with an “X” on the Ötzi to the right. Damage CIRCLE the area of the mummy that is damaged. Did you know? The arrowhead that caused Ötzi to Did you know: bleed to death wasn’t This damage was caused discovered until 10 years after accidentally by a power tool the mummy was found. during the recovery of the mummy in 1991. Ötzi the iceman Read the panels! Did you know? Did you know? A paper published in 2016 All except one of Ötzi’s shows that Otzi also carried H. fingernails were missing; a pylori, a bacteria associated single detached nail was with stomach ulcers! found by his body! DNA Analysis Scientists identified DNA from different bacteria One of Ötzi’s fingernails had horizontal ridges and other living things. -

Prehistoric Artefact Box: Complete Box

PREHISTORIC ARTEFACT BOX PREHISTORIC ARTEFACT BOX: COMPLETE BOX 1 Antler Retoucheur 11 Leather Cup 2 Flint Retoucheur 12 Flint Scrapers [1 large & 4 x small] in pouch 3 Hammer Stone 13 Flint Arrowheads [x2] in box/pouch 4 Comb 14 Bronze Age Flint arrowhead in pouch 5 Needle & Thread 15 Hair Ornaments [x 2] in pouch 6 Slate Arrow 16 Mesolithic Arrow 7 Small Knife 17 Goddess Figurine 8 Resin Stick 18 Antler Tool 9 Bead Necklace 19 Prehistoric Loan Box- Risk Assessment 10 Hand Axe and Leather Covers 20 Artefact Box Booklet-Prehistoric Acknowledgements The artefacts were made by Emma Berry and Andrew Bates of Phenix Studios Ltd of Hexham, Northumberland. http://www.phenixstudios.com/ ARTEFACT BOX: PREHISTORIC Item: 1 Brief Description: Antler Retoucheur Further Information: This tool is made from antler. It was used to retouch flints-that means it was used to sharpen it by carefully chipping away small flakes away from a stone tool’s edge that had become blunt through use. Mesolithic and Neolithic flaked tools were made with a lot of retouching, as they were very small and very fine. Even Palaeolithic tools could be sharpened by retouching. Explore: The periods of prehistory covered in this artefact box are called: the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic Ages (the Old, Middle and New Stone Ages) and the Bronze Age. What “Age” do we live in today? The Steel Age? The Plastic Age? Is everything we use made of this material? To find out more about each of these Stone Age periods follow this link: http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zpny34j#z98q2hv ARTEFACT BOX: PREHISTORIC Item: 2 Brief Description: Flint Retoucheur Further Information: The tip of this tool was made from antler and the handle is lime wood. -

A Native History of Kentucky

A Native History Of Kentucky by A. Gwynn Henderson and David Pollack Selections from Chapter 17: Kentucky in Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia edited by Daniel S. Murphree Volume 1, pages 393-440 Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA. 2012 1 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW As currently understood, American Indian history in Kentucky is over eleven thousand years long. Events that took place before recorded history are lost to time. With the advent of recorded history, some events played out on an international stage, as in the mid-1700s during the war between the French and English for control of the Ohio Valley region. Others took place on a national stage, as during the Removal years of the early 1800s, or during the events surrounding the looting and grave desecration at Slack Farm in Union County in the late 1980s. Over these millennia, a variety of American Indian groups have contributed their stories to Kentucky’s historical narrative. Some names are familiar ones; others are not. Some groups have deep historical roots in the state; others are relative newcomers. All have contributed and are contributing to Kentucky's American Indian history. The bulk of Kentucky’s American Indian history is written within the Commonwealth’s rich archaeological record: thousands of camps, villages, and town sites; caves and rockshelters; and earthen and stone mounds and geometric earthworks. After the mid-eighteenth century arrival of Europeans in the state, part of Kentucky’s American Indian history can be found in the newcomers’ journals, diaries, letters, and maps, although the native voices are more difficult to hear. -

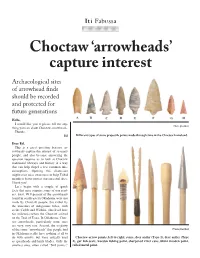

2011.07 Choctaw Arrowheads Capture Interest

Iti Fabussa Choctaw ‘arrowheads’ capture interest Archaeological sites of arrowhead finds should be recorded and protected for future generations Hello, I would like you to please tell me any- Photo provided thing you can about Choctaw arrowheads. Thanks, Ed Different types of stone projectile points made through time in the Choctaw homeland. Dear Ed, This is a great question because ar- rowheads capture the interest of so many people, and also because answering the question requires us to look at Choctaw traditional lifeways and history in a way that can help dispel a few common mis- conceptions. Opening this discussion might even raise awareness to help Tribal members better protect our ancestral sites. Thank you! Let’s begin with a couple of quick facts that may surprise some of our read- ers. First, 99.9 percent of the arrowheads found in southeastern Oklahoma were not made by Choctaw people, but rather by the ancestors of indigenous tribes, such as the Caddo and Wichita, who lived here for millennia before the Choctaw arrived on the Trail of Tears. In Oklahoma, Choc- taw arrowheads, particularly stone ones are very, very rare. Second, the majority of the stone “arrowheads” that people find Photo provided in Oklahoma really have nothing at all to do with arrows, but were actually used Choctaw arrow points, left to right; stone, deer antler (Type 1), deer antler (Type as spearheads and knife blades. Only the 2), gar fish scale, wooden fishing point, sharpened river cane, blunt wooden point, smallest ones, often called “bird points,” rolled metal point. were put on the end of arrows. -

Groundwater Quality in the Bear Valley and Lake Arrowhead Watershed, California

U.S. Geological Survey and the California State Water Resources Control Board Groundwater Quality in the Bear Valley and Lake Arrowhead Watershed, California Groundwater provides more than 40 percent of California’s drinking water. To protect this vital resource, the State of California created the Groundwater Ambient Monitoring and Assessment (GAMA) Program. The Priority Basin Project of the GAMA Program provides a comprehensive assessment of the State’s groundwater quality and increases public access to groundwater-quality information. The Bear Valley and Lake Arrowhead Watershed study areas in southern California compose one of the study units being evaluated. The Bear Valley and Lake Arrowhead Watershed Overview of Water Quality Study Unit Inorganic Organic constituents constituents The Bear Valley and Lake Arrowhead Watershed study unit covers about 112 square 1 8 miles (290 square kilometers) in the San Bernardino Mountains of southern California. The 9 13 Bear Bear Valley study area is an alluvium-filled valley surrounding Big Bear and Baldwin Lakes 78 Valley and corresponds to the Bear Valley groundwater basin (California Department of Water 91 Resources, 2003). The Lake Arrowhead Watershed study area consists primarily of granitic 8 Lake bedrock and includes parts of six watersheds around Lake Arrowhead (Mathany and Burton, 34 25 2017). Arrowhead 41 Watershed 92 117°15' 117° 116°45' California e r ve Riv Bear Valley Aqueduct ja CONSTITUENT CONCENTRATIONS o study area M Baldwin High Moderate Low or not detected Big Lake (dry) Bear EXPLANATION Silverwood Lake Lake Values indicate percentages of the area of the ground- 34° Lake Arrowhead Lithology water resources used for public drinking water with 15' ek concentrations in the specified categories. -

Example of a Doctor of Philosophy Title Page

The Acquisition of Skill in Early Flaked Stone Technologies: An Experimental Study Submitted by Nada Nazem Khreisheh to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology In November 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract This thesis describes the experimental work carried out as part of the Learning to be Human Project, investigating skill and learning in early flaked stone technologies. A group of 16 volunteers were studied as they learnt skills in Oldowan style flaking, Acheulean handaxe technology and Levallois preferential flake technologies. Aptitude, practice hours and hours spent in taught sessions were recorded and skill in each of these technologies was assessed at regular intervals. This information was used to answer questions concerning the acquisition of high level skill in these technologies, the role of practice, teaching and aptitude in determining skill in terms of connaissance and savoir-faire and the archaeological visibility of skill. At a more in depth level the significance of these findings for cognitive capacities of early hominins and the evolution of modern human brains and intelligence was assessed. The results of these experiments allowed the identification of the greater impact of teaching on Acheulean handaxe and Levallois technology compared to Oldowan style flaking. -

Medieval Arrowheads from Oxfordshire

Medieval Arrowheads from Oxfordshire Richard Wadge SUMMARY The main evidence for civilian archery in medieval England is documentary, but this can be supplemented by the physical evidence of arrowheads. These are found in most large collections of artefacts in England, and, although they are catalogued and described, their contribution to an account of how archery was practised by English people in the Middle Ages is rarely analysed. This article examines the medieval arrowheads held by the Oxfordshire County Museums Service to see what can be learnt about the practice of archery in the county. The practical experience of modern archers using the traditional English longbow is brought to bear on the discussion. he story of archery in medieval England is often recounted in terms of outlaws, such as Robin THood, and military successes in great battles, such as Crécy and Agincourt. The skills of the English (and Welsh) military archers had great significance in the history of Western Europe for about two and a half centuries. Such archers became an established part of a mythical history of England: for example, the Arthur Machen story ‘The Bowmen’, published in September 1914, in which longbowmen help soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force, or the propaganda elements in Laurence Olivier’s film of Henry V, released in 1944. These military skills depended on and grew out of the practice of archery by the people of England and Wales in the Middle Ages. The importance of archery skills to the national security of medieval England is demonstrated in a series of royal proclamations and statutes. -

A Comparison of Penetration and Damage Caused by Different Types of Arrowheads on Loose and Tight Fit Clothing

Accepted Manuscript A comparison of penetration and damage caused by different types of arrowheads on loose and tight fit clothing Nichole MacPhee, Anne Savage, Nikolas Noton, Eilidh Beattie, Louise Milne, Joanna Fraser PII: S1355-0306(17)30137-5 DOI: doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2017.11.005 Reference: SCIJUS 704 To appear in: Science & Justice Received date: 16 January 2017 Revised date: 16 November 2017 Accepted date: 21 November 2017 Please cite this article as: Nichole MacPhee, Anne Savage, Nikolas Noton, Eilidh Beattie, Louise Milne, Joanna Fraser , A comparison of penetration and damage caused by different types of arrowheads on loose and tight fit clothing. The address for the corresponding author was captured as affiliation for all authors. Please check if appropriate. Scijus(2017), doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2017.11.005 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. This accepted manuscript is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribuiton- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT A comparison of penetration and damage caused by different types of arrowheads on loose and tight fit clothing Nichole