Serie Nouă Vol. VIII Nr. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity?

Special Volume 6 (2016): Space and Knowledge. Topoi Research Group Articles, ed. by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, pp. 777–818. Svend Hansen – Jürgen Renn – Florian Klimscha – Jochen Büttner – Barbara Helwing – Sebastian Kruse The Digital Atlas of Innovations: A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity Edited by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, Excellence Cluster Topoi, Berlin eTopoi ISSN 2192-2608 http://journal.topoi.org Except where otherwise noted, content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 Svend Hansen – Jürgen Renn – Florian Klimscha – Jochen Büttner – Barbara Helwing – Sebastian Kruse The Digital Atlas of Innovations: A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity The authors discuss the simultaneous appearance of technological innovations in three key technologies (metallurgy, wheeled vehicles, weighing systems) in the second half of the 4th millennium. This is done from a source-critical perspective because the innova- tions are discussed with the help of dynamic maps from the Topoi project Digital Atlas of Innovations. Besides indications of diffusion gradients influenced by special research conditions, exceptional waves of innovation can be detected for all three technologies in the discussed period. These waves of innovation cannot, however, be generalized but have to be understood on the basis of the respective technology traditions and lines of devel- opment specific to local areas. Monocentric diffusion theories can be clearly disproven, local technology developments and their converging in certain centrally situated regions have to be assumed instead. Similarly, the transfer of objects and their châine opératoire can only be detected rather infrequently, while the adaptation to local socio-economic and environmental factors can be demonstrated. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

Hafting and raw materials from animals. Guide to the identification of hafting traces on stone tools Veerle ROTS Prehistoric Archaeology Unit Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Geo-Institute Celestijnenlaan 200E (Pb: 02409), B-3001 Leuven, Heverlee (Belgique) [email protected] Rots V. 2008. – Hafting and raw materials from animals. Guide to the identification of hafting traces on stone tools. [DVD-ROM]1 . Anthropozoologica 43 (1): 43-66. ABSTRACT Stone tool hafting has been a widely discussed topic, but its identifica- tion on a prehistoric level has long been hampered. Given the organic nature of hafting arrangements, few remains are generally preserved. An overview is presented of animal materials that can be used for haft- ing stone tools, and examples are provided of preserved hafting arrangements made out of animal raw material. Based on the same principles as those determining the formation of use-wear traces on stone tools, it is argued that hafting traces are formed and can be iden- tified. The variables influencing the formation of hafting traces are KEY WORDS discussed. Specific wear patterns and trace attributes are provided for Stone tools, use-wear, different hafting arrangements that use animal raw material. It is hafting, concluded that the provided referential data allow for the identifi- wear pattern, experiments, cation of hafted stone tools on prehistoric sites and the identification animal raw material. of the hafting arrangement used. RÉSUMÉ Emmanchements et matières premières animales. Un guide pour l’identification des traces d’emmanchement sur des outils de pierre. Le sujet des emmanchements des outils de pierre a été largement discuté, mais leurs identifications à un niveau préhistorique ont longtemps été difficiles. -

Morphology of Modern Arrowhead Tips on Human Skin Analog*

J Forensic Sci, January 2018, Vol. 63, No. 1 doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13502 PAPER Available online at: onlinelibrary.wiley.com PATHOLOGY/BIOLOGY LokMan Sung,1,2 M.D.; Kilak Kesha,3 M.D.; Jeffrey Hudson,4,5 M.D.; Kelly Root,1 and Leigh Hlavaty,1,2 M.D. Morphology of Modern Arrowhead Tips on Human Skin Analog* ABSTRACT: Archery has experienced a recent resurgence in participation and has seen increases in archery range attendance and in chil- dren and young adults seeking archery lessons. Popular literature and movies prominently feature protagonists well versed in this form of weap- onry. Periodic homicide cases in the United States involving bows are reported, and despite this and the current interest in the field, there are no manuscripts published on a large series of arrow wounds. This experiment utilizes a broad selection of modern arrowheads to create wounds for comparison. While general appearances mimicked the arrowhead shape, details such as the presence of abrasions were greatly influenced by the design of the arrowhead tip. Additionally, in the absence of projectiles or available history, arrowhead injuries can mimic other instruments causing penetrating wounds. A published resource on arrowhead injuries would allow differentiation of causes of injury by forensic scientists. KEYWORDS: forensic science, forensic pathology, compound bow, arrow, broadhead, morphology Archery, defined as the art, practice, and skill of shooting arrows While investigations into the penetrating ability of arrows with a bow, is indelibly entwined in human history. Accounts of have been published (5), this article is the first large-scale study the bow and arrow can be chronicled throughout human civiliza- evaluating the cutaneous morphology of modern broadhead tion from its origins as a primary hunting tool, migration to utiliza- arrow tip injuries in a controlled environment. -

Questions of Hafting Technology, Use and Adaptation in the Neolithic Lake

Questions of hafting technology, use and adaptation in the Neolithic lake-dwelling sites (a case study of antler sleeves from "Swiss collection"stored in Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia) Madina Galimova∗1 1Institute of Archaeology named after A.Kh. Khalikov of the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences (IA TAS) { Butlerov str.,30, Kazan, 420012, the Republic of Tatarstan, Russian Federation, Russia Abstract "Swiss collection" in National Museum of Tatarstan Republic was probably obtained in 1882 by professor N.F. Vysotsky from lake-dwelling sites revealed on the lake Neuchatel. Collection consists of 94 antler sleeves { connection devices between wooden haft and stone axe, adze or cutting blade as well as many tools made from stone and bone (adzes, chisels etc.). Antler sleeve as intermediate device prevented wooden haft from splitting and valuable stone tool from damage. Experimental and technological research carried by J´'org Schibler (2001) proved the presence of two detachment techniques of red deer antler during the Ne- olithic of Switzerland: by means of indentation technique and string-saw one. The sleeves morphology and use-wear demonstrate high standardization methods applied by the experienced inhabitants of lake-shore settlements. Sleeves under study are characterized with a variety of shapes and types, among them: sleeves of cylindrical shape with hafting and mounting holes (4) or with one mounting hole (88) including the sleeves of 4 types depend- ing on the presence or absence of clear-cut hafting part, functional of nonfunctional ledge, remnant of the burr.A specific technical method applied to sleeves with such a remnant was the drilling of holes for mounting to the sleeve to handle. -

Museum of New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies

MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES THE GLOFUETA PROJECT: TEST EXCAVATIONS AT EIGHT PREHISTORIC SITESBETWEEN GLORIETA AND PECOS, NEW MEXICO Yvonne Roye Oakes with a contribution by James L. Moore Submitted by David A. Phillips, Jr., Ph.D. Principal Investigator ARCHAEOLOGY NOTES NO. 45 SANTA FE 1991 NEW MEXICO ADMINISTRATIVE SUMMARY In 1985 and 1986, the Research Section of the Laboratory of Anthropology, Museum of New Mexico, tested ten sites within the limits of the proposed reconstruction on State Road 50 between Glorieta and Pecos, New Mexico (New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department [NMSHTD] Project No. RS-1416[1]) and one site within the project limits at the Glorieta Interchange (NMSHTD Project No. IR-025-5[63]297). The purpose of the testing program was to evaluate the nature and extent of subsurface and surface remains on the sites and to determine their potential to yield significant information on the prehistory and history of the area. Project sites included two historic residential sites, a Pueblo fieldhouse, three rock shelters, and four lithic or sherd artifact scatters. One historic site, Pigeon’s Ranch (LA 49315), is on the National Register of Historic Places. It was the location of an 1850s stagestop on the Santa Fe Trail, a Civil War battle, and a trading post and tourist stop in the 1920s and 1930s. The other historic structure consists of a portion of a house foundation within the right-of-way. The two historic sites (LA 49265 and LA 49315) will be discussed in another volume. Remains of a small Pueblo IV fieldhouse were uncovered during the testing program. -

Jewellery, Watches, Antiquities and Objects of Vertu 17 March 2020 J15

DIX • NOONAN • WEBB JEWELLERY, WATCHES, ANTIQUITIES AND OBJECTS OF VERTU 17 MARCH 2020 J15 VERTU AND OBJECTS OF ANTIQUITIES WATCHES, WEBB JEWELLERY, • DIX • NOONAN www.dnw.co.uk 16 Bolton Street Mayfair London W1J 8BQ 020 7016 1700 [email protected] Jewellery, Watches, Antiquities and Objects of Vertu Tuesday 17th March 2020 at 1pm BOARD of DIRECTORS Pierce Noonan Chairman and CEO 020 7016 1700 [email protected] Nimrod Dix Deputy Chairman 020 7016 1820 [email protected] Robin Greville Chief Technology Officer 020 7016 1750 [email protected] Christopher Webb Head of Coin Department 020 7016 1801 [email protected] AUCTION and CLIENT SERVICES Philippa Healy Head of Administration (Associate Director) 020 7016 1775 [email protected] Emma Oxley Accounts and Viewing 020 7016 1701 [email protected] Christopher Mellor-Hill Head of Client Liaison (Associate Director) 020 7016 1771 [email protected] Chris Finch Hatton Client Liaison 020 7016 1754 [email protected] James King Head of Shipping and Facilities 020 7016 1833 [email protected] JEWELLERY, WATCHES and OBJECTS of VERTU Frances Noble Head of Department (Associate Director) 020 7016 1781 [email protected] Laura Smith Specialist 020 7016 1782 [email protected] Jessica Edmonds Junior Specialist and Auction Clerk 020 7016 1782 [email protected] COINS, TOKENS and COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS Christopher Webb Head of Department (Director) 020 7016 1801 [email protected] Peter Preston-Morley Specialist (Associate Director) 020 7016 1802 [email protected] Jim Brown Specialist 020 7016 1803 [email protected] Tim Wilkes Specialist -

Ötzi the Iceman Worksheets

From mummies to mitochondria, skeletons to sequencing, Denisovans to DNA, molecules to murder…. Our human Inheritance Understanding our genetic ancestry & what makes us human featuring Ötzi the iceman Look at the mummy! Did you know: The Making of Ötzi’s Replica What type of images were used to make Ötzi’s ancient tattoos were the 3D print of Ötzi? made by making fine cuts in his skin and then rubbing charcoal in the cuts. Where in Italy is the real mummy stored? Ancient Ink Ötzi has 57 visible tattoos in the form of small lines and crosses. (4 cannot be seen.) Fatal Wound FIND and DRAW as many tattoos as you can on the illustration of the iceman’s mummy Evidence suggests that Ötzi was shot by (each line counts as a single tattoo; a cross an arrow, and this caused his death. would count as two). MARK the location of the arrow wound with an “X” on the Ötzi to the right. Damage CIRCLE the area of the mummy that is damaged. Did you know? The arrowhead that caused Ötzi to Did you know: bleed to death wasn’t This damage was caused discovered until 10 years after accidentally by a power tool the mummy was found. during the recovery of the mummy in 1991. Ötzi the iceman Read the panels! Did you know? Did you know? A paper published in 2016 All except one of Ötzi’s shows that Otzi also carried H. fingernails were missing; a pylori, a bacteria associated single detached nail was with stomach ulcers! found by his body! DNA Analysis Scientists identified DNA from different bacteria One of Ötzi’s fingernails had horizontal ridges and other living things. -

Homes for Hunters? Exploring the Concept of Home at Hunter-Gatherer Sites in Upper Paleolithic Europe and Epipaleolithic Southwest Asia

Current Anthropology Volume 60, Number 1, February 2019 91 Homes for Hunters? Exploring the Concept of Home at Hunter-Gatherer Sites in Upper Paleolithic Europe and Epipaleolithic Southwest Asia by Lisa A. Maher and Margaret Conkey In both Southwest Asia and Europe, only a handful of known Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic sites attest to aggregation or gatherings of hunter-gatherer groups, sometimes including evidence of hut structures and highly structured use of space. Interpretation of these structures ranges greatly, from mere ephemeral shelters to places “built” into a landscape with meanings beyond refuge from the elements. One might argue that this ambiguity stems from a largely functional interpretation of shelters that is embodied in the very terminology we use to describe them in comparison to the homes of later farming communities: mobile hunter-gatherers build and occupy huts that can form campsites, whereas sedentary farmers occupy houses or homes that form communities. Here we examine some of the evidence for Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic structures in Europe and Southwest Asia, offering insights into their complex “functions” and examining perceptions of space among hunter-gatherer communities. We do this through examination of two contemporary, yet geographically and culturally distinct, examples: Upper Paleolithic (especially Magdalenian) evidence in Western Europe and the Epipaleolithic record (especially Early and Middle phases) in Southwest Asia. A comparison of recent evidence for hut structures from these regions suggests several similarities in the nature of these structures, their association with activities related to hunter-gatherer aggregation, and their being “homes” imbued with quotidian and symbolic meaning. All of this is my home temporary, yet geographically and culturally distinct, exam- these fjords rivers lakes ples: the EP record (especially Early and Middle phases) in the cold the sunlight the storms Southwest Asia and the UP (especially Magdalenian) evidence The night and day of the fields in Western Europe. -

Prehistoric Artefact Box: Complete Box

PREHISTORIC ARTEFACT BOX PREHISTORIC ARTEFACT BOX: COMPLETE BOX 1 Antler Retoucheur 11 Leather Cup 2 Flint Retoucheur 12 Flint Scrapers [1 large & 4 x small] in pouch 3 Hammer Stone 13 Flint Arrowheads [x2] in box/pouch 4 Comb 14 Bronze Age Flint arrowhead in pouch 5 Needle & Thread 15 Hair Ornaments [x 2] in pouch 6 Slate Arrow 16 Mesolithic Arrow 7 Small Knife 17 Goddess Figurine 8 Resin Stick 18 Antler Tool 9 Bead Necklace 19 Prehistoric Loan Box- Risk Assessment 10 Hand Axe and Leather Covers 20 Artefact Box Booklet-Prehistoric Acknowledgements The artefacts were made by Emma Berry and Andrew Bates of Phenix Studios Ltd of Hexham, Northumberland. http://www.phenixstudios.com/ ARTEFACT BOX: PREHISTORIC Item: 1 Brief Description: Antler Retoucheur Further Information: This tool is made from antler. It was used to retouch flints-that means it was used to sharpen it by carefully chipping away small flakes away from a stone tool’s edge that had become blunt through use. Mesolithic and Neolithic flaked tools were made with a lot of retouching, as they were very small and very fine. Even Palaeolithic tools could be sharpened by retouching. Explore: The periods of prehistory covered in this artefact box are called: the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic Ages (the Old, Middle and New Stone Ages) and the Bronze Age. What “Age” do we live in today? The Steel Age? The Plastic Age? Is everything we use made of this material? To find out more about each of these Stone Age periods follow this link: http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zpny34j#z98q2hv ARTEFACT BOX: PREHISTORIC Item: 2 Brief Description: Flint Retoucheur Further Information: The tip of this tool was made from antler and the handle is lime wood. -

A Native History of Kentucky

A Native History Of Kentucky by A. Gwynn Henderson and David Pollack Selections from Chapter 17: Kentucky in Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia edited by Daniel S. Murphree Volume 1, pages 393-440 Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA. 2012 1 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW As currently understood, American Indian history in Kentucky is over eleven thousand years long. Events that took place before recorded history are lost to time. With the advent of recorded history, some events played out on an international stage, as in the mid-1700s during the war between the French and English for control of the Ohio Valley region. Others took place on a national stage, as during the Removal years of the early 1800s, or during the events surrounding the looting and grave desecration at Slack Farm in Union County in the late 1980s. Over these millennia, a variety of American Indian groups have contributed their stories to Kentucky’s historical narrative. Some names are familiar ones; others are not. Some groups have deep historical roots in the state; others are relative newcomers. All have contributed and are contributing to Kentucky's American Indian history. The bulk of Kentucky’s American Indian history is written within the Commonwealth’s rich archaeological record: thousands of camps, villages, and town sites; caves and rockshelters; and earthen and stone mounds and geometric earthworks. After the mid-eighteenth century arrival of Europeans in the state, part of Kentucky’s American Indian history can be found in the newcomers’ journals, diaries, letters, and maps, although the native voices are more difficult to hear. -

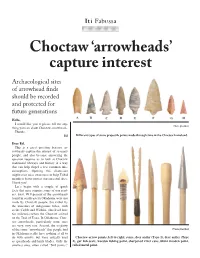

2011.07 Choctaw Arrowheads Capture Interest

Iti Fabussa Choctaw ‘arrowheads’ capture interest Archaeological sites of arrowhead finds should be recorded and protected for future generations Hello, I would like you to please tell me any- Photo provided thing you can about Choctaw arrowheads. Thanks, Ed Different types of stone projectile points made through time in the Choctaw homeland. Dear Ed, This is a great question because ar- rowheads capture the interest of so many people, and also because answering the question requires us to look at Choctaw traditional lifeways and history in a way that can help dispel a few common mis- conceptions. Opening this discussion might even raise awareness to help Tribal members better protect our ancestral sites. Thank you! Let’s begin with a couple of quick facts that may surprise some of our read- ers. First, 99.9 percent of the arrowheads found in southeastern Oklahoma were not made by Choctaw people, but rather by the ancestors of indigenous tribes, such as the Caddo and Wichita, who lived here for millennia before the Choctaw arrived on the Trail of Tears. In Oklahoma, Choc- taw arrowheads, particularly stone ones are very, very rare. Second, the majority of the stone “arrowheads” that people find Photo provided in Oklahoma really have nothing at all to do with arrows, but were actually used Choctaw arrow points, left to right; stone, deer antler (Type 1), deer antler (Type as spearheads and knife blades. Only the 2), gar fish scale, wooden fishing point, sharpened river cane, blunt wooden point, smallest ones, often called “bird points,” rolled metal point. were put on the end of arrows. -

Birch-Bark Hats and Elite Status in Iron Age Europe Cara Melissa Reeves University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2015 Head and Shoulders Above the Rest: Birch-Bark Hats and Elite Status in Iron Age Europe Cara Melissa Reeves University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Reeves, Cara Melissa, "Head and Shoulders Above the Rest: Birch-Bark Hats and Elite Status in Iron Age Europe" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1036. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1036 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HEAD AND SHOULDERS ABOVE THE REST: BIRCH-BARK HATS AND ELITE STATUS IN IRON AGE EUROPE by Cara Reeves A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2015 ABSTRACT HEAD AND SHOULDERS ABOVE THE REST: BIRCH-BARK HATS AND ELITE STATUS IN IRON AGE EUROPE by Cara Reeves The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold As competition between Celtic elites increased in Iron Age continental Europe (c. 800- 25/15 BC), ornamentation of the head figured prominently in status displays across the Celtic world. Mortuary and iconographic contexts reveal that headgear made of both metal and organic materials marked elite status, but materials varied regionally by gender and age throughout the Iron Age.