The Historical and Symbolical Origin of the Chorten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Way of the White Clouds: the Classic Spiritual Travelogue by One of Tibets Best- Known Explorers Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE WAY OF THE WHITE CLOUDS: THE CLASSIC SPIRITUAL TRAVELOGUE BY ONE OF TIBETS BEST- KNOWN EXPLORERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lama Anagarika Govinda | 320 pages | 02 Feb 2006 | Ebury Publishing | 9781846040115 | English | London, United Kingdom The Way of the White Clouds: The Classic Spiritual Travelogue by One of Tibets Best-Known Explorers PDF Book Remove from wishlist failed. This is travel at an extremely difficult level. A fascinating biography of Freda Bedi, an English woman who broke all the rules of gender, race, and religious background to become both a revolutionary in the fight for Indian independence and then a Buddhist icon. SJRod Catalogue Number: Visitors to Milford Sound will not be disappointed - it is truly spectacular. Thank to this book, I found my own way. By: Matthieu Ricard - editor and translator , and others. Classicism Paperback Books. Listeners also enjoyed Though these old, conditioned attempts to control our life may offer fleeting relief, ultimately they leave us feeling isolated and mired in pain. He then leverages his story to explain a frankly metaphysical component of the Tibetan Buddhist worldview. Join Heritage Expeditions, pioneers in authentic small ship expedition cruising, as we explore New Zealand's remote southern Fascinating descriptions of pre invasion Tibet and the esoteric practices of Tibetan Buddhism. Audible Premium Plus. No, I won't be convinced. Discover the Chatham Islands along with the many bird species that call these islands home. Lama Yeshe didn't see a car until he was 15 years old. Contact Us. Govinda describes experiences that he must have known non- Buddhists would be likely to dismiss outright - for example, the lung-gom-pa monks who can cross improbable distances through the mountains while in a trance state - so he backs into wonder. -

Proceedings of Conference on Indian Culture Held in Mumbai University on 16Th – 17Th September 2011

Proceedings of Conference on Indian Culture held in Mumbai University on 16th – 17th September 2011 Organized by Institute of Indo-Aryan Studies in association with Department of Philosophy University of Mumbai PROCEEDINGS OF CONFERENCE ON INDIAN CULTURE Conference held in Mumbai University, Mumbai 16th – 17th September 2011 Organized by Institute of Indo-Aryan Studies in association with Department of Philosophy, University of Mumbai Editors Dr. (Mrs.) Meenal Katarnikar Reader, Department of Philosophy, University of Mumbai Dr. Debesh C. Patra Member, Institute of Indo-Aryan Studies Contact [email protected] [email protected] Website: www.srisrithakuranukulchandra.com Copyright © Institute of Indo-Aryan Studies 2011 Price: Rs. 125/- GUIDE TO THE PROCEEDINGS Editorial Conference on Indian Culture - vii Confluence of Multiple Streams of Research Dr. (Mrs.) Meenal Katarnikar and Dr. Debesh C. Patra Keynote Address 1. Indian Culture – An Integration of Eternity and Science 1 Dr. Tapan Kumar Jena 2. Education and Spirituality 7 Dr. B.S.K. Naidu Theme 1 : Balanced Growth of a Person 3. Accomplishment, Achievement & Success – Do, Be & Get: Theory 13 of Action as Propounded by Sri Sri Thakur Anukul Chandra Dr. Debesh C. Patra 4. Three Pillars of Man Making Mission 29 Dr. Srikumar Mukherjee 5. Marriage and Procreation : Its Cultural Context 37 Dr. Bharat Vachharajani Theme 2 : Social Dynamics on a Spiritual Foundation 6. Hindu Law of Woman’s Property 60 Dr. Anagha Joshi 7. Status of Woman Ascetics in Jaina and Buddhist Tradition 65 Prof. Archana S. Malik-Goure 8. Social Dynamics in Madhvacarya’s Bhagavata Dharma 78 Mrs. Mita M. Shenoy Theme 3 : Comparative Religion 9. -

Chakra 4: Anahata- the Heart Chakra Anahata the 4Th Chakra Is Located at the Centre of Your Chest at the Level of the Heart

Chakra 4: Anahata- The Heart Chakra Anahata the 4th chakra is located at the centre of your chest at the level of the heart. Physically, it controls the lungs, heart, thymus and secondary glands of the chest. Air is the main element. It corresponds with to the subtle energies of our galaxy, It bestows love, affection, selflessness and high aesthetic and intellectual feelings. Anahata shows conscience and compassion when it is balanced. It's all about how you manifest love, forgive others, and your feelings. This is a powerful chakra, as it is the center of the seven. Three above, three below. Matter and spirit are united. This is a very powerful location in the body. It is directly connected to the Third Eye-Ajna 6th and the Crown- Sahasara chakra 7th. Anahata is all about love. We may feel love one day and angry and resentful the next. We may have both some deficient and excessive characteristics (see chart). The important thing is to examine the basic stance we take in life and work to bring that stance into balance whenever we can. The main healing in the 4th chakra is to accept love, give love but most importantly practice self love and acceptance. Perform the asanas that open the chest and bring the universal energies and love into the heart. As Anahata influences the lungs, Pranayama, yogic breathing exercises are another method of bringing in life and energy into the chest chakra. Pranayama is control of Breath. "Prana" is Breath or vital energy in the body. On subtle levels prana represents the pranic energy responsible for life or life force, and "ayama" means control. -

Alexandra David-Neel in Sikkim and the Making of Global Buddhism

Transcultural Studies 2016.1 149 On the Threshold of the “Land of Marvels:” Alexandra David-Neel in Sikkim and the Making of Global Buddhism Samuel Thévoz, Fellow, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation I look around and I see these giant mountains and my hermit hut. All of this is too fantastic to be true. I look into the past and watch things that happened to me and to others; […] I am giving lectures at the Sorbonne, I am an artist, a reporter, a writer; images of backstages, newsrooms, boats, railways unfold like in a movie. […] All of this is a show produced by shallow ghosts, all of this is brought into play by the imagination. There is no “self” or “others,” there is only an eternal dream that goes on, giving birth to transient characters, fictional adventures.1 An icon: Alexandra David-Neel in the global public sphere Alexandra David-Neel (Paris, 1868–Digne-les-bains, 1969)2 certainly ranks among the most celebrated of the Western Buddhist pioneers who popularized the modern perception of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism at large.3 As is well known, it is her illegal trip from Eastern Tibet to Lhasa in 1924 that made her famous. Her global success as an intrepid explorer started with her first published travel narrative, My Journey to Lhasa, which was published in 1927 1 Alexandra David-Néel, Correspondance avec son mari, 1904–1941 (Paris: Plon, 2000), 392. Translations of all quoted letters are mine. 2 This work was supported by the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research under grant PA00P1_145398: http://p3.snf.ch/project-145398. -

Western Buddhist Teachers

Research Article Journal of Global Buddhism 2 (2001): 123 - 138 Western Buddhist Teachers By Andrew Rawlinson formerly Lecturer in Buddhism University of Lancaster, England [email protected] Copyright Notes Digitial copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no charge is made and no alteration ismade to the content. Reproduction in any other format with the exception of a single copy for private study requires the written permission of the author. All enquries to [email protected] http://jgb.la.psu.edu Journal of Global Buddhsim 123 ISSN 1527-6457 R e s e a r c h A r t i c l e Western Buddhist Teachers By Andrew Rawlinson formerly Lecturer in Buddhism University of Lancaster, England [email protected] Introduction The West contains more kinds of Buddhism than has ever existed in any other place. The reason for this is simple: the West discovered Buddhism (and in fact all Eastern traditions) at a time when modern communications and transport effectively made the West a single entity. Previously, Buddhism (and all Eastern traditions) had developed in relative isolation from each other. In principle, there is no reason why we could not find every Buddhist tradition in Tokyo, or Bangkok. But we do not. And again the reason is simple: Eastern Buddhist traditions were not looking outside themselves for a different kind of Buddhism. The West, on the other hand, was prepared to try anything. So the West is the only "open" direction that Eastern traditions can take. But when they do, they are inevitably subjected to the Western way of doing things: crossing boundaries and redefining them. -

The Journal of the International Association for Bon Research

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR BON RESEARCH ✴ LA REVUE DE L’ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE POUR LA RECHERCHE SUR LE BÖN New Horizons in Bon Studies 3 Inaugural Issue Volume 1 – Issue 1 The International Association for Bon Research L’association pour la recherche sur le Bön c/o Dr J.F. Marc des Jardins Department of Religion, Concordia University 1455 de Maisonneuve Ouest, R205 Montreal, Quebec H3G 1M8 Logo: “Gshen rab mi bo descending to Earth as a Coucou bird” by Agnieszka Helman-Wazny Copyright © 2013 The International Association for Bon Research ISSN: 2291-8663 THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR BON RESEARCH – LA REVUE DE L’ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE POUR LA RECHERCHE SUR LE BÖN (JIABR-RAIRB) Inaugural Issue – Première parution December 2013 – Décembre 2013 Chief editor: J.F. Marc des Jardins Editor of this issue: Nathan W. Hill Editorial Board: Samten G. Karmay (CNRS); Nathan Hill (SOAS); Charles Ramble (EPHE, CNRS); Tsering Thar (Minzu University of China); J.F. Marc des Jardins (Concordia). Introduction: The JIABR – RAIBR is the yearly publication of the International Association for Bon Research. The IABR is a non-profit organisation registered under the Federal Canadian Registrar (DATE). IABR - AIRB is an association dedicated to the study and the promotion of research on the Tibetan Bön religion. It is an association of dedicated researchers who engage in the critical analysis and research on Bön according to commonly accepted scientific criteria in scientific institutes. The fields of studies represented by our members encompass the different academic disciplines found in Humanities, Social Sciences and other connected specialities. -

Bhagavad Gita

BHAGAVAD GITA The Global Dharma for the Third Millennium Chapter Eight Translations and commentaries compiled by Parama Karuna Devi Copyright © 2012 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. Title ID:4173071 ISBN-13: 978-1482548471 ISBN-10: 148254847X published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center phone: +91 94373 00906 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com © 2011 PAVAN Chapter 8: Taraka brahma yoga The Yoga of transcendental liberation The 8th chapter of Bhagavad gita, entitled "The Yoga of liberating spiritual consciousness" takes us further into the central part of the discussion, focused on the development of bhakti - love and devotion for God. The topic of devotion is difficult to analyze because it deals with emotions rather than intellect and logic. However, devotion is particularly popular and powerful in changing people's lives, specifically because it works on people's feelings. Feelings and emotions fill up the life of a living being even on the material level and constitute the greatest source of joy and sorrow. All the forms of physical joys and sufferings depend on emotional joy and suffering: a different emotion in the awareness transforms hell into heaven, and heaven into hell. Attraction and attachment (raga) as well as repulsion and aversion (dvesa) are created by emotions, and these two polarities constitute the entire universe of material action and identification. It is impossible for a conditioned soul to ignore feelings or emotions, or to get rid of them. Usually, those who try to deny sentiments and emotions simply repress them, and we know that repressed sentiments and emotions become stronger and take deeper roots, consciously or unconsciously branching into a number of obsessive behaviors causing immense sufferings to the individual and to the people around him/her. -

Clearing & Balancing Anahata Chakra

Living In Love Clearing & Balancing Anahata Chakra Pranayama: Nadi Sodhana a.k.a Alternate Nostril Breathing Also called balancing breath, this is simple form of alternate nostril breathing is suitable for all. Nadi means channel and refers to the energy pathways through which prana flows. Shodhana means cleansing therefore nadi shodhana means channel cleaning. The practice calms the mind, soothes anxiety and stress, balances left and right hemispheres and promotes clear thinking. Sit comfortably on the ground or in a chair. Hold your right hand up and curl your index and middle fingers toward your palm. Place your thumb next to your right nostril and your ring finger and pinky by your left. Close the right nostril with your thumb, and inhale through the left nostril. Breathe slow, steady and full. Now close the left nostril by pressing gently against it with your ring finger and pinky, and open your right nostril by relaxing your thumb. Exhale fully with a slow and steady breath out the right side. Inhale again through the right nostril, close it, and then exhale through the left side. That's one complete round. To summarize: ! *Inhale through the left !*Exhale through the right !*Inhale through the right nostril !!*Exhale through the left Begin with 5-10 rounds and add more as you feel ready. Remember to keep your breathing slow, easy and full. You can do this just about any time and anywhere. Try it as a mental warm-up before meditation to help calm the mind. You can also do it as part of your centering before practicing asana. -

Theosophist V7 N76 January 1886

THE THEOSOPHIST. • " ' >' ' ' i ' ■ ~ •' -// ' 1 ’ ; Opinions of the Press. ; I T loots elegant in its new shape and may iu appearance compare favourably with the British Magazines. Thero is much variety irt the matter too, We wish our metamorphosed Cou* temporary a long and .prosperous career .-^Tribune (Lahore). The new size is that of the generality of Reviews and Magazines, and is certainly more agreeable to the Bight, as also tnore handy for use than the old one. The joanml with this (Ootober) number enters upon its seventh year. Its prosperity is increasing with the spread of Theosophy. We wish the magazine continued sucoess —Mahratia. THE It appears in a new and more handy form, which is a decided improvement on the preceding numbers, and contains some purely literary articles that will well repay perusal. Besides these there is the usual number of contributions on the mybtic sciences and Other cognate subjects. —Statesman, ' ' THEOSOPHIST The proprietors of the Theosophint have adopted a new and convenient size for their magazine. No. 73, Vol. VII contains fourteen articles, some of them being very useful and well written, besides correspondence and reviews ou various subjects, aud essays. It is altogether a very A MAGAZINE OF : useful publication,—Nydya Sudha, ORIENTAL PHILOSOPHY, ART, LITERATURE AND OCCULTISM. We are glad to see our frieud the Theosophist appearing in a moro handy and attractive garb. The new size will be found acceptable to all readers. The contents of the last issue also C o n d u c t e d b y H . P . B l a v a t s k t . -

Hinduism's Treatment of Untouchables

Introduction India is one of the world's great civilizations. An ancient land, vast and complex, with a full and diverse cultural heritage that has enriched the world. Extending back to the time of the world's earliest civilizations in an unbroken tradition, Indian history has seen the mingling of numerous peoples, the founding of great religions and the flourishing of science and philosophy under the patronage of grand empires. With a great reluctance to abandon traditions, India has grown a culture that is vast and rich, with an enormous body of history, legend, theology, and philosophy. With such breadth, India offers a multitude of adventuring options. Many settings are available such as the high fantasy Hindu epics or the refined British Empire in India. In these settings India allows many genres. Espionage is an example, chasing stolen nuclear material in modern India or foiling Russian imperialism in the 19th century. War is an option; one could play a soldier in the army of Alexander the Great or a proud Rajput knight willing to die before surrender. Or horror in a dangerous and alien land with ancient multi-armed gods and bloodthirsty Tantric sorcerers. Also, many styles are available, from high intrigue in the court of the Mogul Emperors to earnest quests for spiritual purity to the silliness of Mumbai "masala" movies. GURPS India presents India in all its glory. It covers the whole of Indian history, with particular emphasis on the Gupta Empire, the Moghul Empire, and the British Empire. It also details Indian mythology and the Hindu epics allowing for authentic Indian fantasy to be played. -

The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, Or All Three?

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 4-20-2020 The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, or All Three? Kathryn Heislup Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Heislup, Kathryn, "The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, or All Three?" (2020). Student Research Submissions. 325. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/325 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, or All Three? A Look Into the Subtle Physiology of Traditional and Modern Forms of Yoga Kathryn E. Heislup RELG 401: Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Major in Religion University of Mary Washington April 20, 2020 2 Notions of subtle body systems have migrated and changed throughout India and Tibet over many years with much controversy; the movement of these ideas to the West follows a similar controversial path, and these developments in both Asia and the West exemplify how one cannot identify a singular, legitimate, “subtle body”. Asserting that there is only one legitimate teaching, practice, and system of the subtle body is problematic and inappropriate. The subtle body refers to assumed energy points within the human body that cannot be viewed by the naked eye, but is believed by several traditions to be part of our physical existence. Indo-Tibetan notions of a subtle body do include many references to similar ideas when it comes to this type of physiology, but there has never been one sole agreement on a legitimate identification or intended use. -

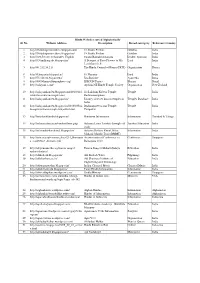

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore