The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, Or All Three?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I on an Empty Stomach After Evacuating the Bladder and Bowels

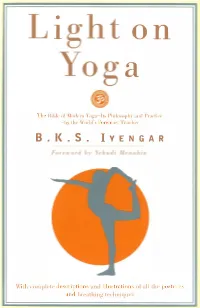

• I on a Tllt' Bi11lr· ol' \lodt•nJ Yoga-It� Philo�opl1� and Prad il't' -hv thr: World" s Fon-·mo �l 'l'r·ar·lwr B • I< . S . IYENGAR \\ it h compldc· dt·!wription� and illustrations of all tlw po �tun·� and bn·athing techniqn··� With More than 600 Photographs Positioned Next to the Exercises "For the serious student of Hatha Yoga, this is as comprehensive a handbook as money can buy." -ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION "The publishers calls this 'the fullest, most practical, and most profusely illustrated book on Yoga ... in English'; it is just that." -CHOICE "This is the best book on Yoga. The introduction to Yoga philosophy alone is worth the price of the book. Anyone wishing to know the techniques of Yoga from a master should study this book." -AST RAL PROJECTION "600 pictures and an incredible amount of detailed descriptive text as well as philosophy .... Fully revised and photographs illustrating the exercises appear right next to the descriptions (in the earlier edition the photographs were appended). We highly recommend this book." -WELLNESS LIGHT ON YOGA § 50 Years of Publishing 1945-1995 Yoga Dipika B. K. S. IYENGAR Foreword by Yehudi Menuhin REVISED EDITION Schocken Books New 1:'0rk First published by Schocken Books 1966 Revised edition published by Schocken Books 1977 Paperback revised edition published by Schocken Books 1979 Copyright© 1966, 1968, 1976 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

Pranayama: Breath of Life

SPECIAL SECTION: PRANAYAMA: BREATH OF LIFE P RANAYAMA : U NIQ U E G IFT OF THE Y O G IC T RADITION By Gary Kraftsow your asana and pranayama Gary Kraftsow asserts that pranayama is among the most uniquely potent parts of Yoga practice. He explains that there’s no other tradition that has the sophistication of the yogic science of breath. In this article, he eloquently explains the ways you can use pranayama to create the effects you want in your practice. He shows how your asana practice can serve your pranayama practice, your pranayama practice can serve your asana practice and both practices together can serve your meditation practice. The Three Stages of Life 1. Asana as preparation for pranayama: Our focus is not about the structural details of the asana—we are Most Yoga practitioners today are in what we would call preparing the body and breath for pranayama. In this the midday stage of life. This is an image used in Viniyoga: breath-centric asana, the emphasis is on controlling and sunrise being the first 25 or 30 years of life, midday being lengthening the inhale and exhale and on the appropriate that long period extending up into the mid-70s and the use of retention of breath after inhalation and suspension sunset stage of life usually comes after the age of 75. In the of breath after exhalation in specific parts of asana practice. sunrise stage of life, the focus of our practice is on asana with a primarily structural orientation. In the midday stage 2. -

A Translation of the Vijñāna-Bhairava-Tantra (Complete but Lacking Commentary) ©2017 by Christopher Wallis Aka Hareesh

A translation of the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra (complete but lacking commentary) ©2017 by Christopher Wallis aka Hareesh Introductory verse (maṅgala-śloka): “Shiva is also known as ‘Bhairava’ because He brings about the [initial awakening that makes us] cry out in fear of remaining in the dreamstate (bhava-bhaya)—and due to that cry of longing he becomes manifest in the radiant domain of the heart, bestowing absence of fear (abhaya) for those who are terrified. He is also known as Bhairava because he is the Lord of those who delight in his awesome roar (bhīrava), which signals the death of Death! Being the Master of that flock of excellent Yogins who tire of fear and seek release, he is Bhairava—the Supreme, whose form is Consciousness (vijñāna). As the giver of nourishment, he extends his Power throughout the universe!” ~ the great master Rājānaka Kṣemarāja, c. 1020 CE Like most Tantrik scriptures, the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra (c. 850 CE) takes the form of a dialogue between Śiva and Śakti, here called Bhairava and Bhairavī. It begins with the Goddess asking Bhairava: śrutaṃ deva mayā sarvaṃ rudra-yāmala-saṃbhavam | trika-bhedam aśeṣeṇa sārāt sāra-vibhāgaśaḥ || 1 || . 1. O Lord, I have heard the entire teaching of the Trika1 that has arisen from our union, in scriptures of ever greater essentiality, 2. but my doubts have not yet dissolved. What is the true nature of Reality, O Lord? Does it consist of the powers of the mystic alphabet (śabda-rāśi)?2 3. Or, amongst the terrifying forms of Bhairava, is it Navātman?3 Or is it the trinity of śaktis (Parā, Parāparā, and Aparā) that [also] constitute the three ‘heads’ of Triśirobhairava? 4. -

An Excursus on the Subtle Body in Tantric Buddhism. Notes

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A. K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS L. M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University of Vienna Patiala, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, fapan Bardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson FJRN->' Volume 6 1983 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES A reconstruction of the Madhyamakdvatdra's Analysis of the Person, by Peter G. Fenner. 7 Cittaprakrti and Ayonisomanaskdra in the Ratnagolravi- bhdga: Precedent for the Hsin-Nien Distinction of The Awakening of Faith, by William Grosnick 35 An Excursus on the Subtle Body in Tantric Buddhism (Notes Contextualizing the Kalacakra)1, by Geshe Lhundup Sopa 48 Socio-Cultural Aspects of Theravada Buddhism in Ne pal, by Ramesh Chandra Tewari 67 The Yuktisas(ikakdrikd of Nagarjuna, by Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti 94 The "Suicide" Problem in the Pali Canon, by Martin G. Wiltshire \ 24 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Buddhist and Western Philosophy, edited by Nathan Katz 141 2. A Meditators Diary, by Jane Hamilton-Merritt 144 3. The Roof Tile ofTempyo, by Yasushi Inoue 146 4. Les royaumes de I'Himalaya, histoire et civilisation: le La- dakh, le Bhoutan, le Sikkirn, le Nepal, under the direc tion of Alexander W. Macdonald 147 5. Wings of the White Crane: Poems of Tskangs dbyangs rgya mtsho (1683-1706), translated by G.W. Houston The Rain of Wisdom, translated by the Nalanda Transla tion Committee under the Direction of Chogyam Trungpa Songs of Spiritual Change, by the Seventh Dalai Lama, Gyalwa Kalzang Gyatso 149 III. -

SWAMI YOGANANDA and the SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP a Successful Hindu Countermission to the West

STATEMENT DS213 SWAMI YOGANANDA AND THE SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP A Successful Hindu Countermission to the West by Elliot Miller The earliest Hindu missionaries to the West were arguably the most impressive. In 1893 Swami Vivekananda (1863 –1902), a young disciple of the celebrated Hindu “avatar” (manifestation of God) Sri Ramakrishna (1836 –1886), spoke at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago and won an enthusiastic American following with his genteel manner and erudite presentation. Over the next few years, he inaugurated the first Eastern religious movement in America: the Vedanta Societies of various cities, independent of one another but under the spiritual leadership of the Ramakrishna Order in India. In 1920 a second Hindu missionary effort was launched in America when a comparably charismatic “neo -Vedanta” swami, Paramahansa Yogananda, was invited to speak at the International Congress of Religious Liberals in Boston, sponsored by the Unitarian Church. After the Congress, Yogananda lectured across the country, spellbinding audiences with his immense charm and powerful presence. In 1925 he established the headquarters for his Self -Realization Fellowship (SRF) in Los Angeles on the site of a former hotel atop Mount Washington. He was the first Eastern guru to take up permanent residence in the United States after creating a following here. NEO-VEDANTA: THE FORCE STRIKES BACK Neo-Vedanta arose partly as a countermissionary movement to Christianity in nineteenth -century India. Having lost a significant minority of Indians (especially among the outcast “Untouchables”) to Christianity under British rule, certain adherents of the ancient Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism retooled their religion to better compete with Christianity for the s ouls not only of Easterners, but of Westerners as well. -

Thriving in Healthcare: How Pranayama, Asana, and Dyana Can Transform Your Practice

Thriving in Healthcare: How pranayama, asana, and dyana can transform your practice Melissa Lea-Foster Rietz, FNP-BC, BC-ADM, RYT-200 Presbyterian Medical Services Farmington, NM [email protected] Professional Disclosure I have no personal or professional affiliation with any of the resources listed in this presentation, and will receive no monetary gain or professional advancement from this lecture. Talk Objectives Provide a VERY brief history of yoga Define three aspects of wellness: mental, physical, and social. Define pranayama, asana, and dyana. Discuss the current evidence demonstrating the impact of pranayama, asana, and dyana on mental, physical, and social wellness. Learn and practice three techniques of pranayama, asana, and dyana that can be used in the clinic setting with patients. Resources to encourage participation from patients and to enhance your own practice. Yoga as Medicine It is estimated that 21 million adults in the United States practice yoga. In the past 15 years the number of practitioners, of all ages, has doubled. It is thought that this increase is related to broader access, a growing body of research on the affects of the practice, and our understanding that ancient practices may hold the key to healing modern chronic diseases. Yoga: A VERY Brief History Yoga originated 5,000 or more years ago with the Indus Civilization Sanskrit is the language used in most Yogic scriptures and it is believed that the principles of the practice were transmitted by word of mouth for generations. Georg Feuerstien divides the history of Yoga into four catagories: Vedic Yoga: connected to ritual life, focus the inner mind in order to transcend the limitations of the ordinary mind Preclassical Yoga: Yogic texts, Upanishads and the Bhagavad-Gita Classical Yoga: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, the eight fold path Postclassical Yoga: Creation of Hatha (willful/forceful) Yoga, incorporation of the body into the practice Modern Yoga Swami (master) Vivekananda speaks at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. -

Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2015 Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks Kimberley J. Pingatore As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Pingatore, Kimberley J., "Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks" (2015). MSU Graduate Theses. 3010. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3010 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, Religious Studies By Kimberley J. Pingatore December 2015 Copyright 2015 by Kimberley Jaqueline Pingatore ii BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS Religious Studies Missouri State University, December 2015 Master of Arts Kimberley J. -

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII. -

Tantra Reborn

The New Yoga TANTRA REBORN On the Sensuality & Sexuality of our immortal Soul Body Peter Wilberg 2007 to my great mother SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special acknowledgements as sources of inspiration, scholarship and citations to: Paul Eduardo Muller-Ortega Mark S.G. Dyczkowski David Peter Lawrence Seth /Jane Roberts Georg Feuerstein Michael Kosok Jaideva Singh Special acknowledgements as sources of spiritual encouragement - and for taking on all the demands of proofing and manuscript preparation - to my loving soulmates - my life partner Karin Heinitz and lifelong fellow traveller Andrew Gara. CONTENTS About Peter Wilberg and The New Yoga .........................................................I Note to the Reader.............................................................................................. V Note by the Author............................................................................................VI CHAPTER 1...................................................................................... 12 Invitation to The New Yoga ............................................................................12 Your Immortal Body .........................................................................................14 What are ‘Yoga’ and ‘Meditation’?...................................................................16 Medotation as Embodied Relating ..................................................................17 What's new about ‘The New Yoga’? ...............................................................19 CHAPTER 2 -

Development and Validation of a Tantric Sex Scale: Sexual-Mindfulness, Spiritual Purpose, and Genital/Orgasm De-Emphasis

DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF A TANTRIC SEX SCALE: SEXUAL- MINDFULNESS, SPIRITUAL PURPOSE, AND GENITAL/ORGASM DE-EMPHASIS Brandon Lee Gordon A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2018 Committee: Joshua Grubbs, Advisor Anne Gordon Kenneth Pargament © 2018 Brandon L. Gordon All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Joshua Grubbs, Advisor Tantra is a religious tradition that holds sex as nourishing to the spiritual life. Within popular culture and scholarly works alike, there are reports claiming that tantric sex results in deepening intimacy, increasing sexual passion, and increasing relational and sexual satisfaction. To date, there is a complete absence of empirical research concerning the purported effects of tantric sex. Given the reported benefits associated with tantric sex, there is a basis for empirical inquiry. This study examined tantra empirically by developing, testing, and validating a brief measure of tantric sexual practice. Additionally, this work demonstrates how this measure of tantric sex might predict relevant outcomes such as relationship and sexual satisfaction. An exploratory factor analysis approach was used with a goal of reducing a large item bank (81 items) to a briefer, 25-item scale. Three subscales emerged: Sexual-mindfulness, Spiritual Purpose, and Genital/orgasm De-emphasis. Further hypothesis testing was conducted using both correlation and regression analyses. Sexual-mindfulness was associated with Relationship and Sexual Satisfaction in correlational and regression analysis. Spiritual Purpose was negatively associated with Relationship Satisfaction in correlational and regression analysis. Genital/orgasm De-emphasis was positively associated with Relationship Satisfaction in correlational and regression analysis.