White Appropriation and Exploitation of Black Appearance and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete?

Fordham Law Review Volume 86 Issue 6 Article 12 2018 Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete? Kevin Brown Indiana University Maurer School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Brown, Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete?, 86 Fordham L. Rev. 2773 (2018). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol86/iss6/12 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLUTION OF THE RACIAL IDENTITY OF CHILDREN OF LOVING: HAS OUR THINKING ABOUT RACE AND RACIAL ISSUES BECOME OBSOLETE? Kevin Brown* It is a special honor for me to have this opportunity to discuss the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion in Loving v. Virginia1 at a Symposium held in honor of its fiftieth anniversary. I served on the panel entitled “The Children of Loving,”2 which for me has two connotations. First, as an African American who married a white woman twenty years after the decision, I am a child of Loving in the sense that I was in an interracial marriage. But as a father of two black-white biracial children, I am also a father of two Loving children. -

Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology Versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 21:31 Atlantis Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice Études critiques sur le genre, la culture, et la justice Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta Volume 39, numéro 2, 2018 Résumé de l'article This article explores how race and gender become distinguished from each URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1064075ar other in contemporary scholarly and activist debates on the comparison DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1064075ar between transracialism and transgender identities. The article argues that transracial-transgender distinctions often reinforce divides between Aller au sommaire du numéro autological (self-determined) and genealogical (inherited) aspects of subjectivity and obscure the constitution of this division through modern technologies of power. Éditeur(s) Mount Saint Vincent University ISSN 1715-0698 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Dutta, A. (2018). Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism. Atlantis, 39(2), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064075ar All Rights Reserved © Mount Saint Vincent University, 2018 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Special Section: Research Allegories ofGender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta is an Assistant Professor in the de- Introduction: Two Scenes ofTransgender partments of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies Recognition and Asian and Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Iowa. -

TDS-MAP58: Identidades Mal Entendidas. Raza Y Clase En El

traficantes de sueños Traficantes de Sueños no es una casa editorial, ni si- quiera una editorial independiente que contempla la publicación de una colección variable de textos crí- ticos. Es, por el contrario, un proyecto, en el sentido estricto de «apuesta», que se dirige a cartografiar las líneas constituyentes de otras formas de vida. La cons- trucción teórica y práctica de la caja de herramientas que, con palabras propias, puede componer el ciclo de luchas de las próximas décadas. Sin complacencias con la arcaica sacralidad del libro, sin concesiones con el narcisismo literario, sin lealtad alguna a los usurpadores del saber, TdS adopta sin ambages la libertad de acceso al conocimiento. Queda, por tanto, permitida y abierta la reproducción total o parcial de los textos publicados, en cualquier formato imaginable, salvo por explícita voluntad del autor o de la autora y sólo en el caso de las ediciones con ánimo de lucro. Omnia sunt communia! mapas 58 Mapas. Cartas para orientarse en la geografía variable de la nueva composición del trabajo, de la movilidad entre fron- teras, de las transformaciones urbanas. Mutaciones veloces que exigen la introducción de líneas de fuerza a través de las discusiones de mayor potencia en el horizonte global. Mapas recoge y traduce algunos ensayos, que con lucidez y una gran fuerza expresiva han sabido reconocer las posibili- dades políticas contenidas en el relieve sinuoso y controver- tido de los nuevos planos de la existencia. © 2018, Asad Haider © 2020, de esta edición, Traficantes de Sueños creative cc commons Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 3.0 España (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) Usted es libre de: * Compartir - copiar, distribuir, ejecutar y comunicar públicamente la obra Bajo las condiciones siguientes: * Reconocimiento — Debe reconocer los créditos de la obra de la manera especificada por el autor o el licenciante (pero no de una manera que sugiera que tiene su apoyo o que apoyan el uso que hace de su obra). -

The Rhetoric of Cool: Computers, Cultural Studies, and Composition

THE RHETORIC OF COOL: COMPUTERS, CULTURAL STUDIES, AND COMPOSITION By JEFFREY RICE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Eage ABSTRACT iv 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1963 12 Baudrillard 19 Cultural Studies 33 Technology 44 McLuhan’s Cool Media as Computer Text 50 Cyberculture 53 Writing 57 2 LITERATURE 61 Birmingham and Baraka 67 The Role of Literature 69 The Beats 71 Burroughs 80 Practicing a Burroughs Cultural Jamming 91 Eating Texts 96 Kerouac and Nostalgia 100 History VS Nostalgia 104 Noir 109 Noir Means Black 115 The Signifyin(g) Detective 124 3 FILM AND MUSIC 129 The Apparatus 135 The Absence of Narrative 139 Hollywood VS The Underground 143 Flaming Creatures 147 The Deviant Grammar 151 Hollywood VS The Underground 143 Scorpio Rising 154 Music: Blue Note Records 163 Hip Hop - Samplin’ and Skratchin’ 170 The Breaks 174 ii 1 Be the Machine 178 Musical Production 181 The Return of Nostalgia 187 4 COMPOSITION 195 Composition Studies 200 Creating a Composition Theory 208 Research 217 Writing With(out) a Purpose 221 The Intellectual Institution 229 Challenging the Institution 233 Technology and the Institution 238 Cool: Computing as Writing 243 Cool Syntax 248 The Writer as Hypertext 25 Conclusion: Living in Cooltown 255 5 REFERENCES 258 6 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH ...280 iii Abstract of Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE RHETORIC OF COOL: COMPUTERS, CULTURAL STUDIES, AND COMPOSITION By Jeffrey Rice December 2002 Chairman: Gregory Ulmer Major Department: English This dissertation addresses English studies’ concerns regarding the integration of technology into the teaching of writing. -

An Aesthetic of the Cool: West Africa

An Aesthetic of the Cool Author(s): Robert Farris Thompson Source: African Arts, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973), pp. 40-43+64-67+89-91 Published by: UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3334749 . Accessed: 19/10/2014 02:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center and Regents of the University of California are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to African Arts. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Sun, 19 Oct 2014 02:46:11 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions An Aesthetic of the Cool ROBERTFARRIS THOMPSON T he aim of this study is to deepen the understandingof a of elements serious and pleasurable, of responsibility and of basic West African/Afro-American metaphor of moral play. aesthetic accomplishment, the concept cool. The primary Manifest within this philosophy of the cool is the belief metaphorical extension of this term in most of these cultures that the purer, the cooler a person becomes, the more ances- seems to be control,having the value of composurein the indi- tral he becomes. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

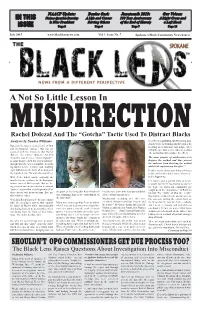

Rachel Dolezal and the “Gotcha” Tactic Used to Distract Blacks Analysis by Sandra Williams Be Defined As Pointing out the Wrong Way

NAACP Update: Denise Osei: Juneteenth 2015: Our Voices: IN THIS Naima Quarles-Burnley A Life and Career 150 Year Anniversary A Right Cross and is New President Serving Others of the End of Slavery a Left Hook ISSUE Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 13 July 2015 www.blacklensnews.com Vol. 1 Issue No. 7 Spokane’s Black Community News Source A Not So Little Lesson In MISDIRECTIONRachel Dolezal And The “Gotcha” Tactic Used To Distract Blacks Analysis by Sandra Williams be defined as pointing out the wrong way. Another way of defining misdirection is by Based on the unprecedented level of fury focusing on its function. Any magic effect and international “outrage” that was as- (what the spectator sees) requires a method sociated with the discovery that Rachel (the method used to produce the effect). Dolezal, the former Spokane NAACP President, was in fact a “white imposter”, The main purpose of misdirection is to as some people called her, you would have disguise the method and thus prevent thought that she was responsible for pull- the audience from detecting the method ing out her service revolver and emptying whilst still experiencing the effect.” eight bullets into the back of an unarmed, In other words, doing something to distract fleeing black man. No wait, that wasn’t her. people so that they don’t notice what is ac- Well, if she didn’t murder anybody, she tually happening. must be the one to blame for the dispropor- If it wasn’t such a painful thing to watch, tionate rates of Black people that are be- it would have been fascinating to observe ing arrested and incarcerated in a criminal the degree to which our community got “justice” system that actually profits off of caught up in the “importance” of Rachel’s the point of declaring that Rachel Dolezal I had no idea at the time how profound that those arrests and incarcerations. -

Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering Kelly Best

Document generated on 09/30/2021 1:10 p.m. Ethnologies “Making Cool Things Hot Again” Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering Kelly Best Hommage à Peter Narváez Article abstract In Honour of Peter Narváez This article critically examines instances of blackface in Newfoundland Volume 30, Number 2, 2008 Christmas mummering. Following Peter Narváez’s call for analysis of expressive culture from folklore and cultural studies approaches, I explore the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/019953ar similarities between these two cultural phenomena. I see them as attempts to DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/019953ar work out racial and class tensions among the underclasses dwelling in burgeoning seaport towns along the North American seaboard that were intimately connected, at that time, through heavily-trafficked shipping routes. I See table of contents offer a reanalysis of the tradition that goes beyond unconscious, symbolic ritualism to one that examines mummering in a historical context. As such, I present evidence which troubles widely held understandings of Christmas Publisher(s) mummering as an English-derived calendar custom. Association Canadienne d'Ethnologie et de Folklore ISSN 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Best, K. (2008). “Making Cool Things Hot Again”: Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering. Ethnologies, 30(2), 215–248. https://doi.org/10.7202/019953ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Accumulation and Avant-Garde Apparel

Confente 1 Oriana Confente Accumulation and Avant-Garde Apparel In his essay, “A Marginal System: Collecting,” French sociologist Jean Baudrillard writes: “Let us grant that our everyday objects are in fact objects of a passion – the passion for private property, emotional investment in which is every bit as intense as investment in the ‘human’ passions… they become mental precincts over which I hold sway, they become things of which I am the meaning, they become my property and my passion” (Baudrillard 259). A leading theorist on the discussion of consumerism, Baudrillard uses a semiotic analysis to explore the materialistic nature of contemporary culture and the integral role of object ownership in the lives of human beings. Accumulating items offers purpose and can contribute to an individual’s security as a person. This can be tied to the fashion industry, with a focus on clothing and dress. Fashion has been long understood to have a sociological function as “a social process of mutual adaptation” wherein “actors are free to decide if and to what extent they will adopt a new object, practice, or representation” (Aspers and Godart 185). The meaning behind choices of apparel influences the consumption of this aspect of culture, as Roland Barthes (a contemporary of Baudrillard who was at the forefront of semiotics) suggests “there is a ‘lexicon and syntax’ in clothing that resembles the structure of language” (Aspers and Godart 183). The desire to speak through the items one wears only heightens the urge to collect particular objects which would open those lines of communication. This is especially true in the realm of current high fashion – “expensive, fashionable clothes produced by leading fashion houses” which are not to be confused with the cheaply constructed, mass-produced items of the fast fashion world (“High Fashion, noun”). -

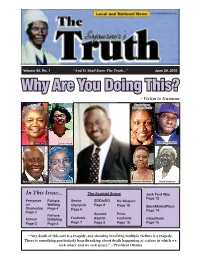

Why Are You Doing This? - Victim to Gunman

Volume 34, No. 1 “And Ye Shall Know The Truth...” June 24, 2015 Why Are You Doing This? - Victim to Gunman Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor Ethel Lance Cynthia Hurd Tywanza Sanders Rev. Daniel Simmons Myra Thompson Rev. Clementa Pinckney Sharonda Singleton Susie Jackson In This Issue... The Soulcial Scene Jack Ford Way Page 12 Perryman Fathers Senior ZOOtoDO No Weapon on Walking Olympics Page 8 Page 10 BlackMarketPlace Charleston Page 4 Page 6 Page 14 Page 2 Fathers Second Price Tolliver Dribbling Festivals Baptist Fashions Classifieds Page 3 Page 5 Page 7 Page 9 Page 16 Page 15 “Any death of this sort is a tragedy, any shooting involving multiple victims is a tragedy. There is something particularly heartbreaking about death happening at a place in which we seek solace and we seek peace.” - President Obama Page 2 The Sojourner’s Truth June 24, 2015 Jesus and Violence Dr. Donald L. Perryman – By Rev. Donald L. Perryman, D.Min. The Truth Contributor Father to his Daughters, ...The tensions which we witness in the world Father to the Community today are indicative of the fact that a new By Tracee Perryman Guest Column world is being born and an old world is pass- Dr. Donald L. Perryman has been a mentor ing away. and father-figure to so many in the church, -- Martin Luther King, Jr. in “The Birth of a New Age” and in the community. Today, I want to focus on the father he was at home. Father/daugh- ter relationships are very complex. Fathers The Christian commands to “Love your en- parent very differently from mothers. -

The Jedi of Japan

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Trinity Publications (Newspapers, Yearbooks, The Trinity Papers (2011 - present) Catalogs, etc.) 2016 The Jedi of Japan David Linden Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/trinitypapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Linden, David, "The Jedi of Japan". The Trinity Papers (2011 - present) (2016). Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford, CT. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/trinitypapers/45 The Jedi of Japan David Linden The West’s image today of the Japanese samurai derives in large part from the works of Japanese film directors whose careers flourished in the period after the Second World War. Foremost amongst these directors was Akira Kurosawa and it is from his films that Western audiences grew to appreciate Japanese warriors and the main heroes and villains in the Star Wars franchise were eventually born. George Lucas and the first six films of the Star Wars franchise draw heavily from Kurosawa’s films, the role of the samurai in Japanese culture, and Bushido—their code. In his book, The Samurai Films of Akira Kurosawa, David Desser explains how Kurosawa himself was heavily influenced by Western culture and motifs and this is reflected in his own samurai films which “embod[y] the tensions between Japanese culture and the new American ways of the occupation” (Desser. 4). As his directorial style matured during the late forties, Kurosawa closely examined Western films and themes such as those of John Ford, and sought to apply the same themes, techniques and character development to Japanese films and traditions.