Virtual Rusophonia: Language Policy As 'Soft Power' in the New Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association for Slavic, East European, & Eurasian Studies

1 Association for Slavic, East European, & Eurasian Studies 46th Annual Convention • November 20-23, 2014 San Antonio Marriott Rivercenter • San Antonio, TX “25 Years After the Fall of the Berlin Wall: Historical Legacies and New Beginnings” Stephen E. Hanson, College of William and Mary ASEEES Board President We are most grateful to our sponsors for their generous support. GOLD SPONSOR: East View Information Services BRONZE SPONSORS: College of William and Mary Reves Center for International Studies National Research University Higher School of Economics Indiana University Russian and East European Institute • University of Texas, Austin Center for Russian, Eastern European and Eurasian Studies and Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies 2 Contents Convention Schedule Overview ..................................................................................................... 2 List of the Meeting Rooms at the Marriott Rivercenter .............................................................. 3 Visual Anthropology Film Series ................................................................................................4-5 Diagram of Meeting Rooms ............................................................................................................ 6 Exhibit Hall Diagram ....................................................................................................................... 7 Index of Exhibitors, Alphabetical ................................................................................................... 8 -

Russians Abroad-Gotovo.Indd

Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) The Real Twentieth Century Series Editor – Thomas Seifrid (University of Southern California) Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) GReta n. sLobin edited by Katerina Clark, nancy Condee, dan slobin, and Mark slobin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: The bibliographic data for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-214-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61811-215-6 (electronic) Cover illustration by A. Remizov from "Teatr," Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College. Cover design by Ivan Grave. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Table of Contents Foreword by Galin Tihanov ....................................... -

The Search for a New Russian National Identity

THE SEARCH FOR A NEW RUSSIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY: RUSSIAN PERSPECTIVES BY DR. JAMES H. BILLINGTON The Library of Congress AND DR. KATHLEEN PARTHÉ University of Rochester Part of the Project on Russian Political Leaders Funded by a Carnegie Foundation Grant to James H. Billington and the Library of Congress Issued by The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. February 2003 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 3 THE FIRST COLLOQUIUM ........................................................................... 5 THE SECOND COLLOQUIUM.................................................................. 31 THE THIRD COLLOQUIUM ....................................................................... 60 AFTERWORD.............................................................................................................. 92 ENDNOTES .................................................................................................................... 99 PARTICIPANTS ...................................................................................................... 101 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................. 106 3 INTRODUCTION by James H. Billington This work combines and condenses the final reports on three colloquia I held in Russia with Dr. Kathleen Parthé on the search for a Russian national identity in the post-Soviet era. The colloquia, as well as two seminars at the Library of Congress in 1996 and 1997 -

American Diplomatic Despatches About the Internal Conditions in the Soviet Union, 1917-1933

ABSTRACT Title of Document: REPORTING FROM THE FRONTLINES OF THE FIRST COLD WAR: AMERICAN DIPLOMATIC DESPATCHES ABOUT THE INTERNAL CONDITIONS IN THE SOVIET UNION, 1917-1933 Asgar M. Asgarov, Ph.D., 2007 Directed By: Associate Professor Michael David-Fox, Department of History Following the Bolshevik Revolution in November of 1917, the United States ended diplomatic relations with Russia, and refused to recognize the Soviet regime until 1933 when President Franklin Roosevelt reversed this policy. Given Russia’s vast size and importance on the world stage, Washington closely monitored the internal developments in that country during the non-recognition period. This dissertation is study of the American diplomatic despatches about the political, economic and social conditions in the USSR in its formative years. In addition to examining the despatches as a valuable record of the Soviet past, the dissertation also explores the ways in which the despatches shaped the early American attitudes toward the first Communist state and influenced the official policy. The American diplomats, stationed in revolutionary Russia and later, in the territories of friendlier nations surrounding the Soviet state, prepared regular reports addressing various aspects of life in the USSR. Following the evacuation of the American diplomatic personnel from Russia toward the end of the Civil War, the Western visitors to Russia, migrants, and Soviet publications became primary sources of knowledge about the Soviet internal affairs. Under the guidance of the Eastern European Affairs Division at the U.S. State Department, the Americans managed to compile great volumes of information about the Soviet state and society. In observing the chronological order, this dissertation focuses on issues of particular significance and intensity such as diplomatic observers’ treatment of political violence, repression and economic hardships that engulfed tumultuous periods of the Revolution, Civil War, New Economic Policy and Collectivization. -

Soviet Journalism and the Journalists' Union, 1955-1966

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Reporting Socialism: Soviet Journalism and the Journalists' Union, 1955-1966 Mary Catherine French University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation French, Mary Catherine, "Reporting Socialism: Soviet Journalism and the Journalists' Union, 1955-1966" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1277. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1277 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1277 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reporting Socialism: Soviet Journalism and the Journalists' Union, 1955-1966 Abstract This dissertation is a historical investigation of the Journalists' Union of the Soviet Union, the first creative union for media professionals in the USSR, and the first study of a creative profession after the death of Stalin. While socialist journalism had existed since before the 1917 revolutions, journalists were not incorporated into a professional body until 1959, several decades after their counterparts in other creative professions. Using sources from Russian and American archives together with published documents, I investigated the reasons for the organization's formation and its domestic and creative work to "develop professional mastery" in its members at home while advancing the Soviet cause abroad. Chapter one explores the reasons for the Journalists' Union's formation, and the interrelationship between Soviet cultural diplomacy and domestic professionalization. Chapter two describes Journalists' efforts to make sense of the immediate aftermath of de-Stalinization, through a case study of the Communist Youth League's newspaper. The third chapter describes the creative union's formal establishment and the debates about journalism's value at its inaugural congress. -

Thinking Russian Literature Mythopoetically

The Superstitious Muse: Thinking Russian Literature Mythopoetically Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures and History Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman The Superstitious Muse: Thinking Russian Literature Mythopoetically DAVID MM.. BETHEA Boston 2009 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bethea, David M., 1948- The superstitious muse: thinking Russian literature mythopoetically / David M. Bethea. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-934843-17-8 (hardback) 1. Russian literature — History and criticism. 2. Mythology in literature. 3. Superstition in literature. I. Title. PG2950.B48 2009 891.709—dc22 2009039325 Copyright © 2009 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-17-8 Book design and typefaces by Konstantin Lukjanov© Photo on the cover by Benson Kua Published by Academic Studies Press in 2009 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

The “Russian World” Russia’S Soft Power and Geopolitical Imagination

The “Russian World” Russia’s Soft Power and Geopolitical Imagination Marlene Laruelle May 2015 The “Russian World” Russia’s Soft Power and Geopolitical Imagination Marlene Laruelle May 2015 Table of Contents About CGI The Center on Global Interests (CGI) is a private, nonprofit research institution headquartered in Washington, D.C. CGI aims to offer new, unconventional thinking on global affairs; produce fresh analysis on relations between modern world powers, particularly the US and Russia; and critically I. INTRODUCTION 1 evaluate current global challenges. Our work is intended to help policymakers, journalists, opinion- makers, educators and the general public alike. II. TRAJECTORY OF THE CONCEPT 3 The Center on Global Interests does not take an institutional position on policy issues. The views represented here are the author’s own. III. THE RUSSIAN WORLD AS RUSSIA’S PUBLIC POLICY 9 © 2015 Center on Global Interests All rights reserved. IV. THE RUSSIAN WORLD AND RUSSIAN FOREIGN POLICY 17 1050 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 1000 V. CONCLUSIONS 23 Washington, DC 20036 Phone: +1-202-973-2832 www.globalinterests.org NOTES 26 Cover image: Olga Kuzmina/Center on Global Interests ABOUT THE AUTHOR 29 The full text of this report can be accessed at www.globalinterests.org. Limited print copies are also available. To request a copy, please send an email to [email protected]. Introduction he concept of the “Russian World” (russkii mir) has a long history rooted in the 1990s, but it T was propelled under the media spotlight in 2014, when Russian President Vladimir Putin used Mit to justify Russia’s interference in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. -

Thursday, November 20, 2014 Session 1

Thursday, November 20, 2014 ASEEES Board Meeting - 8:00 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. - Conference Room 11 Registration Desk - 9:00 a.m. - 5:30 p.m. - Registration Desk II Cyber Café Hours – 8:00 a.m. - 5:45 p.m. - Atrium Lounge Exhibit Hall Hours: 4:00 p.m. - 8:00 p.m. - Grand Ballrooms E & F East Coast Consortium of Slavic Library Collections – 8:00 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. Conference Suite 530 Midwest Slavic and Eurasian Library Consortium - 9:00 a.m. -12:00 p.m. - Conference Suite 544 Session 1 – Thursday – 1:00-2:45 pm 1-01 Russian Management Model: From Stalingrad to Present - (Roundtable) - Conference Room 1 Chair: Ilya Kalinin, New Literary Observer (Russia) Denis Konanchuk, Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO (Russia) Jochen Hellbeck, Rutgers, The State U of New Jersey Valery Yakubovich, ESSEC (France) Andrey Shcherbenok, Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO (Russia) 1-02 Conflicting Patriotisms in Contemporary Russia - (Roundtable) - Conference Room 2 Chair: Alexey Golubev, U of British Columbia (Canada) Kaarina Aitamurto, U of Helsinki (Finland) Markku Kangaspuro, U of Helsinki (Finland) Jussi Lassila, U of Helsinki (Finland) 1-03 Varieties and Interpretations of Rus’/Russian Military Interaction with Steppe Nomads: Mongols, Tatars, Kalmyks - (Roundtable) - Conference Room 3 Chair: Heidi M. Sherman, U of Wisconsin-Green Bay Charles J. Halperin, Independent Scholar Lawrence Nathan Langer, U of Connecticut Donald Ostrowski, Harvard U Timothy May, U of North Georgia 1-04 Early Modern Exile and Culture - Conference Room 4 Sponsored by: Early Slavic Studies Association Chair: Isolde Renate Thyret, Kent State U Papers: Konstantin Erusalimskiy, The Russian State U for the Humanities (Russia) "Muscovites in Exile: Transitive 'Other' into East-European 'Selves'" Michael A. -

Vysotsky's Soul Packaged in Tapes

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: “Vysotsky’s Soul Packaged in Tapes": Identity and Russianness in the Music of Vladimir Vysotsky Heather Lynn Miller, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006. Dissertation directed by: Professor Robert C. Provine Division of Musicology and Ethnomusicology School of Music, University of Maryland This study examines the relationship between music, identity, and Russianness as demonstrated by the songs of the bard Vladimir Vysotsky. The career of Vysotsky occurred within the context of Soviet Russia, but more broadly, his songs embody characteristics specific to Russian culture. For this study, I draw on the fields of ethnomusicology, history, and cultural studies to assist in the interpretation of music and identity in a cultural context. By investigating the life and career of this individual, this study serves as a method in which to interpret the identity of a musical performer on multiple levels. I gathered fieldwork data in Moscow, Russia in the summers of 2003 and 2004. Information was gathered from various sites connected to Vysotsky, and from conversations with devotees of his music. The role of identity in musical performance is complex, and to analyze Vysotsky’s Russianness, I trace his artistic work as both ‘official’ actor and ‘unofficial’ musician. Additionally, I examine the lyrics of Vysotsky’s songs for the purposes of relating his identity to Russian culture. In order to define ‘Russianness,’ I survey theoretical perspectives of ethnicity and nationalism, as well as musical and non-musical symbols, such as the Russian soul (dusha), all of which are part of the framework that creates Russian identity. In addition to Russian identity, I also address a performer’s musical identity which focuses mainly on musical composition and performance. -

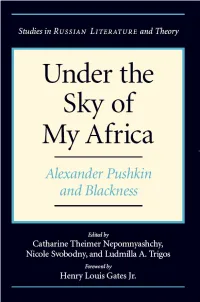

Alexander Pushkin and Blackness

Under the Sky of My Africa Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory Founding Editor Gary Saul Morson General Editor Caryl Emerson Consulting Editors Carol Avins Robert Belknap Robert Louis Jackson Elliott Mossman Alfred Rieber William Mills Todd III Alexander Zholkovsky Under the Sky of My Africa ALEXANDER PUSHKIN AND BLACKNESS Edited by Catharine Theimer Nepomnyashchy, Nicole Svobodny, and Ludmilla A. Trigos Foreword by Henry Louis Gates Jr. NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY PRESS / EVANSTON, ILLINOIS STUDIES OF THE HARRIMAN INSTITUTE Northwestern University Press Evanston, Illinois 60208-4170 Copyright © 2006 by Northwestern University Press. Foreword copyright 2006 by Henry Louis Gates Jr. Published 2006. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10987654321 ISBN 0-8101-1970-6 (cloth) ISBN 0-8101-1971-4 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Under the sky of my Africa : Alexander Pushkin and blackness / edited by Catharine Theimer Nepomnyashchy, Nicole Svobodny, and Ludmilla A. Trigos ; foreword by Henry Louis Gates Jr. p. cm.— (Studies in Russian literature and theory) (Studies of the Harriman Institute) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8101-1971-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)—ISBN 0-8101-1970-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Pushkin, Aleksandr Sergeevich, 1799–1837—Knowledge—Race awareness. 2. Pushkin, Aleksandr Sergeevich, 1799–1837—Family. 3. Racially mixed people—Race identity—Russia. 4. Blacks in literature. 5. Race awareness in literature. 6. Pushkin family. 7. Russia—Ethnic relations. I. Nepomnyashchy, Catharine Theimer. II. Svobodny, Nicole. III. Trigos, Ludmilla A. IV. Series. V. Series: Studies of the Harriman Institute. PG3358.R33.U53 2005 891.71'3—dc22 2005016715 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. -

Andrei Voznesenskii Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0f59q1h4 No online items Guide to the Andrei Voznesenskii Papers Ekaterina K Fleishman Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc/ © 2006 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Andrei Voznesenskii M1399 1 Papers Guide to the Andrei Voznesenskii Papers Collection number: M1399 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Processed by: Ekaterina K Fleishman Date Completed: Feb 2006 Encoded by: Ekaterina K Fleishman, Bill O'Hanlon © 2006 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Andrei Voznesenskii papers Dates: 1955-2004 Collection number: M1399 Creator: Voznesenskii, A. (Andrei) Collection Size: 29 linear ft Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Abstract: Andrei Voznesenskii is one of the foremost poets of post-Stalinist Russia. He is the author of approximately 40 volumes of poetry in Russian, two collections of fiction, at least three plays and two operas. A five-volume set of his collected works appeared in 2000. A number of his works have been translated into English. He has created many works of visual art, in graphic and sculptural form. He was a disciple of Boris Pasternak during his early years. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: EnglishRussian Access Collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least 24 hours in advance of intended use. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the repository. -

Vladimir Nabokov and Women Writers by Mariya D. Lomakina A

Vladimir Nabokov and Women Writers by Mariya D. Lomakina A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Slavic Languages and Literatures) in The University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Olga Y. Maiorova, Co-Chair Professor Omry Ronen, Co-Chair (Deceased) Associate Professor Herbert J. Eagle Professor Yuri Leving, Dalhousie University Associate Professor Andrea P. Zemgulys © Mariya D. Lomakina 2014 Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been written without generous support and encouragement of several people. I am extremely grateful to my dissertation advisor, Omry Ronen, whose energy, sense of humor, dedication to Russian literature, and extraordinary kindness have encouraged many of his students to write and complete their dissertations. He will be greatly missed by me, by his other students, and by all those who knew him. I would like to express my gratitude to the chair of my dissertation committee, Olga Maiorova, for her help and advice on how to proceed with and finish my dissertation. My gratitude also goes to Yuri Leving for his kind interest in my work and his invaluable comments on my topic and dissertation. My ideas grew stronger as a result of conversations with Herbert Eagle, and I thank him for his comments and his endless help with editing my work. My gratitude goes to Andrea Zemgulys, whose insightful comments have also influenced the final outcome of my dissertation. I also wish to thank my friends for their support and interest in my graduation: Sara Feldman, Anjali Purkayastha, Hirak Parikh, and Isaiah Smithson for being good friends in need, the wonderful Stephens family for always being there for me, Chris and Vera Irwin, William and Margaret Dunifon for their hospitality, Brad Damaré and Yana Arnold for spending time together, Mila Shevchenko and Svitlana Rogovyk for their teaching advices, and Jean McKee for her patience in answering all the questions I had.