Jean Sibelius SYMPHONY No.3 · KING CHRISTIAN II, SUITE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Opera Service Bulletin

CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE BULLETIN WINTER, 1972 Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council Central Opera Service • Lincoln Center Plaza • Metropolitan Opera • New York, N.Y. 10023 • 799-3467 Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council Central Opera Service • Lincoln Canter Plaza • Metropolitan Opera • New York, NX 10023 • 799.3467 CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE COMMITTEE ROBERT L. B. TOBIN, National Chairman GEORGE HOWERTON, National Co-Chairman National Council Directors MRS. AUGUST BELMONT MRS. FRANK W. BOWMAN MRS. TIMOTHY FISKE E. H. CORRIGAN, JR. CARROLL G. HARPER MRS. NORRIS DARRELL ELIHU M. HYNDMAN Professional Committee JULIUS RUDEL, Chairman New York City Opera KURT HERBERT ADLER MRS. LOUDON MEI.LEN San Francisco Opera Opera Soc. of Wash., D.C. VICTOR ALESSANDRO ELEMER NAGY San Antonio Symphony Ham College of Music ROBERT G. ANDERSON MME. ROSE PALMAI-TENSER Tulsa Opera Mobile Opera Guild WILFRED C. BAIN RUSSELL D. PATTERSON Indiana University Kansas City Lyric Theater ROBERT BAUSTIAN MRS. JOHN DEWITT PELTZ Santa Fe Opera Metropolitan Opera MORITZ BOMHARD JAN POPPER Kentucky Opera University of California, L.A. STANLEY CHAPPLE GLYNN ROSS University of Washington Seattle Opera EUGENE CONLEY GEORGE SCHICK No. Texas State Univ. Manhattan School of Music WALTER DUCLOUX MARK SCHUBART University of Texas Lincoln Center PETER PAUL FUCHS MRS. L. S. STEMMONS Louisiana State University Dallas Civic Opera ROBERT GAY LEONARD TREASH Northwestern University Eastman School of Music BORIS GOLDOVSKY LUCAS UNDERWOOD Goldovsky Opera Theatre University of the Pacific WALTER HERBERT GIDEON WALDKOh Houston & San Diego Opera Juilliard School of Music RICHARD KARP MRS. J. P. WALLACE Pittsburgh Opera Shreveport Civic Opera GLADYS MATHEW LUDWIG ZIRNER Community Opera University of Illinois See COS INSIDE INFORMATION on page seventeen for new officers and members of the Professional Committee. -

Bpsr N Nte Cei B Nary

5689 FRMS cover:52183 FRMS cover 142 18/02/2013 15:00 Page 1 Spring 2013 No. 158 £2.00 Bulletin RPS bicentenary 5689 FRMS cover:52183 FRMS cover 142 18/02/2013 15:00 Page 2 5689 FRMS pages:Layout 1 20/02/2013 17:11 Page 3 FRMS BULLETIN Spring 2013 No. 158 CONTENTS News and Comment Features Editorial 3 Cover story: RPS Bicentenary 14 Situation becoming vacant 4 A tale of two RPS Gold Medal recipients 21 Vice-President appointment 4 FRMS Presenters Panel 22 AGM report 5 Changing habits 25 A view from Yorkshire – Jim Bostwick 13 International Sibelius Festival 27 Chairman’s column 25 Anniversaries for 2014 28 Neil Heayes remembered 26 Roger’s notes, jottings and ramblings 29 Regional Groups Officers and Committee 30 Central Region Music Day 9 YRG Autumn Day 10 Index of Advertisers Societies Hyperion Records 2 News from Sheffield, Bath, Torbay, Horsham, 16 Arts in Residence 12 Street and Glastonbury, and West Wickham Amelia Marriette 26 Nimbus Records 31 CD Reviews Presto Classical Back cover Hyperion Dohnányi Solo Piano Music 20 Harmonia Mundi Britten and Finzi 20 Dutton Epoch British Music for Viola and orch. 20 For more information about the FRMS please go to www.thefrms.co.uk The editor acknowledges the assistance of Sue Parker (Barnsley Forthcoming Events and Huddersfield RMSs) in the production of this magazine. Scarborough Music Weekend, March 22nd - 25th (page 13) Scottish Group Spring Music Day, April 27th (page 13) th th Daventry Music Weekend, April 26 - 28 (pages 4 & 8) Front cover: 1870 Philharmonic Society poster, courtesy of th West Region Music Day, Bournemouth, June 4 RPS Archive/British Library th FRMS AGM, Hinckley, November 9 EDITORIAL Paul Astell NOTHER AGM HAS PASSED, as has another discussion about falling membership and A the inability to attract new members. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1965-1966

.2 / TANGLEWOOD SEVENTH WEEK August 12, 13, 14, 1966 BERKSHIRE FESTIVAL The Boston Symphony TCHAIKOVSKY CONCERTO No. 1 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN BOSTON SYMPHONY under Leinsdorf ERICH LEINSDORF In an unforgettable performance of Tchaikovsky's Concen No. J, Leinsdorf and one of the world's greatest orchestra combine with Rubinstein in a collaboration that crackles wii power and lyricism. In a supreme test of a pianist's interpn tive powers, Rubinstein brings an emotional and intellectu> lu.vVunm grasp to his playing that is truly incomparable. In another vei Leinsdorf has recorded Prokofieff's Fifth Symphon y as part his growing series of recordings of this master's major work It belongs among recordings elite. Both albums recorded BC» VlCTOK Qynagrooye sound. PR0K0F1EFF: SYMPHONY No. 5 BOSTON SYMPHONY/ LEINSDORF PROKOFIEFF SERIES RCA Victor WfflThe most trusted name in sound BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor Berkshire Festival, Season 1966 TWENTY-NINTH SEASON MUSIC SHED AT TANGLEWOOD, LENOX, MASSACHUSETTS SEVENTH WEEK Historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Assisted by DONALD T. GAMMONS Copyright, 1966 by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The Trustees of The BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. President Vice-President Treasurer Henry B. Cabot Talcott M. Banks John L. Thorndike Philip K. Allen Francis W. Hatch Henry A. Laughlin Abram Berkowitz Andrew Heiskell Edward G. Murray Theodore P. Ferris Harold D. Hodgkinson John T. Noonan Robert H. Gardiner E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. James H. Perkins Sidney R. Rabb Raymond S. Wilkins Trustees Emeritus Palfrey Perkins Lewis Perry Edward A. Taft Oliver Wolcott Tanglewood Advisory Committee Alan J. -

The DETROIT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

W;AD011\T£ROO~ featuring the DETROIT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA PROGRAM, NOTES conducted by CONCERT Page No. CONCERT Page No. SIXTEN EHRLING THURSDAY-FRIDAY, June 30-July 1 77 SUNDAY, July 24 90 SATURDAY·SUNDAY, July 2-3 78 THURSDAY, July 28 93 THURSDAY-FRIDAY, July 7-8 78 FRIDAY, July 29 94 SATURDAY-SUNDAY, July 9-10 .. 81 SATURDAY, July 30 97 THURSDAY·FRIDAY, July 14-15 .. 82 SUNDAY, July 31 98 SATURDAY-SUNDAY, July 16-17 . 85 THURSDAY, Aug. 4 98 JAMES D. HICKS, THURSDAY, July 21 .; 86 FRIDAY, Aug. 5 101 Manager of Meadow Brook Festival FRIDAY, July 22 89 SATURDAY, Aug. 6 102 SATURDAY, July 23 .......•.. 89 SUNDAY, Aug. 7 105 MARY JUNE MA TIHEWS Coordinator of Women's Acth'itit'S PROGRAM CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Third Season - - - - - - - - - - 11 Guest Artists: Planning + People + Great Music = Meadow Brook 20 & 21 Henryk Szeryng, June 30, July 1-2-3 79 Meadow Brook Fe$lival Committees - - - - 28 & 30 Maureen Forrester, July 7-8-9-10 83 Major Donors to 1966 Meadow Brook Festival - - - 37 Van Cliburn, July 14-15-16·17 87 Sponsors of 1966 Meadow Brook Festival - - - 39 & 41 Isaac Stern, July 21·24-30, Aug. 5·7 91 Majar Innovations at Meadow Brook - - - - - 53 Eugene Istomin, July 22-28-31, Aug. 6·7 95 Meadow Brook School of Music - - - 48-49 Leonard Rose, July 23-29, Aug. 4-7 99 Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Sixten Ehrling 71-72 Robert Shaw, July 14-15-16·17, Aug. 11-12-13-14-18 73 Seventh Concert Week, Choral Programs - - - - - 66 Oakland University 60 & 61 Eighth Concert Week, Contemporary Music 67 Istomin-Stern-Rose Special Chamber Concerts - 45 Advertisers' Index ___ ___ __ ___ ______ __ ___ ___ ____ ___ ____ 129 & 130 SINGLE TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE BOX-OFFICE, Pavilion $3, Grounds $1.50, or at the Festival Office, Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan, 48063, Telephone 338-7211, ext. -

Orchestral Works Volume Symphony No

SUPER AUDIO CD Atterberg Orchestral Works Volume Symphony No. 1 3 Symphony No. 5 ‘Sinfonia funebre’ Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra Neeme Järvi (date uncertain) (date the Association of Playwrights and Composers, at Haus der Presse, Berlin Kurt Atterberg, seated nearest right, at an international conference of AKG Images, London / Imagno / Austrian Archives (S) Kurt Atterberg (1887 – 1974) Orchestral Works, Volume 3 Symphony No. 1, Op. 3 (1909 – 11, revised 1913)* 36:46 in B minor • in h-Moll • en si mineur Meinen Eltern gewidmet 1 I Allegro con fuoco – Tranquillo – Tempo I – Tranquillo – Più mosso – Tranquillo – Più mosso – Molto pesante – Tempo I – Tranquillo – Tempo I – Tranquillo – Poco a poco più mosso 9:48 2 II Adagio – 8:30 3 III Presto – Pesante – Tranquillo – Tranquillo – Presto 6:58 4 IV Adagio – Allegro energico – [ ] – Tempo I – Meno mosso – Animando poco a poco – Tempo I – Sempre animando – Largamente – Più pesante 11:24 3 Symphony No. 5, Op. 20 ‘Sinfonia funebre’ (1917 – 22, revised 1947)† 26:25 in D minor • in d-Moll • en ré mineur ‘For each man kills the thing he loves’ 5 Pesante allegro – Molto più mosso – Subito allargando molto – Tempo I – Più vivo – Subito poco largamente – Tempo I – 7:31 6 Lento – 6:35 7 Allegro molto – Tempo vivo – Un poco meno mosso – Adagio – Allegro – Adagio – Allegro – Tempo vivo – Tempo di Valse – Poco tranquillo – Subito poco largamente – Tempo di Valse – Molto tranquillo – Lento 12:20 TT 63:20 Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra (The National Orchestra of Sweden) Sara Trobäck Hesselink* • Per Enoksson† leaders Neeme Järvi 4 Atterberg: Symphonies Nos 1 and 5 Symphony No. -

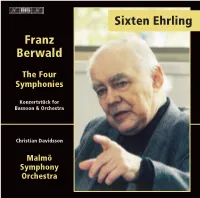

Sixten Ehrling Franz Berwald

Sixten Ehrling Franz Berwald The Four Symphonies Konzertstück for Bassoon & Orchestra Christian Davidsson Malmö Symphony Orchestra BERWALD, Franz Adolf (1796—1868) Disc 1 (BIS-CD-795) [72'20] Sinfonie sérieuse (No. 1) in G minor (1842) 32'10 1 I. Allegro con energia 11'54 2 II. Adagio maestoso 6'51 3 III. Stretto 5'39 4 IV. Finale. Adagio — Allegro molto 7'32 5 Konzertstück für Fagott und Orchester (1827) 11'14 o Allegro non troppo — Andante (con variazioni) — Tempo 1 Christian Davidsson bassoon Sinfonie capricieuse (No. 2) in D major (1842) 27'47 6 I. Allegro 10'38 7 II. Andante 7'15 8 III. Finale. Allegro assai 9'46 2 Disc 2 (BIS-CD-796) [59'00] Sinfonie singulière (No. 3) in C major (1845) 29'19 1 I. Allegro fuocoso 11'42 2 II. Adagio — Scherzo. Allegro assai — Adagio 9'05 3 III. Finale. Presto 8'19 Symphony ‘No. 4’ in E flat major (1845) 28'48 4 I. Allegro risoluto 9'05 5 II. Adagio — attacca — 7'10 6 III. Scherzo. Allegro molto 5'47 7 IV. Finale. Allegro vivace 6'36 TT: 131'20 Malmö Symphony Orchestra (Malmö SymfoniOrkester) Anton Kontra leader Sixten Ehrling conductor Instrumentarium: Christian Davidsson Bassoon: W. Schreiber, Prestige Model 5091, No. 29346. Crook: KD-1 This recording was made possible by generous support from Gambro Group 3 he Berwald family was German; but at some point during the 1770s Ber- wald’s father, Christian Friedrich Georg Berwald (1740–1825) settled in TStock holm. He had studied composition with František Benda among others and would earn his living in Sweden as a violin player in the Royal Opera Orch es- tra (now the Royal Swedish Orchestra), at that time the only professional orchestra in the country. -

THE DETROIT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SIXTEN Ehrling, Music Director and Conductor

,( k, ~,l '. ';. I ":":. \ OUKL ': ARCH ML ; '-':'c:~"\ .~ \I WDOW£ROOfu 38 meadowBrook'72 /~' .02 ~ M47 , ",' Where Nature Sets the Stage. \ ~n_- '~" II 1r1USIee-FESTl~~ 1972 " '- ",\' Oakland University c.3 Rochester, Michigan June 29 through August 27.1972 \ n TICKET PRICES: i I All Thursday, Friday, SatUrday and Sunday concerts plus July 5, 10 and 11: Pavilion $6.00, $5.00 and $4.00 (reserved) Lawn - $2.50 (unreserved) July 12, 19, 26 and August 2 concerts: Lawn or Pavilion - $3.50 (unreserved) BOX OFFICE HOURS Mon. thru Sat.-9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Sun.- 12 Noon to 7 p.m. Phone: 377.2010 FESTIVAL GROUNDS OPEN TWO HOURS PRIOR TO CONCERT TIME ON PERFORMANCE NIGHTS 1972 MEADOW BROOK Schedule THURSDAY - 8:30 P.M. FRIDAY- 8:30 P.M. NON.. SUBSCRIPTION JUNE 29 JUNE 30 DETROITSYMPHONY, DOC SEVERINSEN EVENTS Sixten Ehrling, conductor and His Now Generation Brass ITZHAKPERLMAN,violinist . with Today's Children page 37 page 39 WEDNE Y JULY 6 JULY 7 JULY5-8 .M. MEL TORME THE PENNSYLVANIA BALLET with WOODY HERMAN and his DETROIT SYMPHONY PENNSYLVANIA BALLET Young Thundering Herd DETROIT SYMPHONY page 49 page 51 JULY 13 JULY 14 DETROIT SYMPHONY, \ Monday, Sixten Ehrling, conductor RAY CHARLES Tuesday, JUly EUGENE ISTOMIN, pianist page 59 page 63 ERICK HAWKINS JULY 20 JULY 21 DANCE COMPANY DETROIT SYMPHONY, page 57 Sixten Ehrling, conductor PRESERVATION HALL JAZZ BAND WHITTEMORE & LOWE, WEDNESDAY duo pianists page 71 page 77 JULY 12-8:30 P.M. JULY 27 JULY 28 DETROIT SYMPHONY, BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE Sixten Ehrling, conductor PETER NERO and his Trio ALFRED BRENDEL,pianist page 83 page 87 WEDNESDAY AUGUST 3 AUGUST 4 DETROITSYMPHONY, JULY 19-8:30 P.M. -

David Björkman, Conductor

DAVID BJÖRKMAN, CONDUCTOR David Björkman is one of the latest in a distinguished line of Nordic musicians to move from the concertmaster’s chair to the conductor’s podium. He was a prizewinner at the 2008 Prokofiev International Conducting Competition in St Petersburg and has been a recipient of the Swedish Conductors Award. In 2016, he was appointed chief conductor of Livgardets Dragonmusikkår, the Royal Swedish Cavalry Band, situated in Stockholm. In the near future David returns to the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra, Aarhus Symphony Orchestra and the Nordic Chamber Orchestra apart from his intense concert agenda with Livgardets Dragonmusikkår. During the season 20/21 he returns to conduct productions with Malmö Opera and Piteå Chamber Opera with Norrbotten NEO. Also, he is conducting the Swedish première of Missy Mazzoli’s opera Breaking the waves, produced by the Vadstena Academy. David enjoys ongoing relationships with all the major orchestral ensembles in Sweden. He is equally at home in the theatre, and has conducted at the Royal Swedish Opera, at the Gothenburg Opera, Malmö Opera and five world premières at the Vadstena Academy. David has worked as a guest conductor across the Nordic countries and in Russia and Slovenia. Contemporary music is a vital strand in David’s career. He has presided over the first performance of well over 50 orchestral scores and has introduced new works in the opera house and the ballet theatre. He has conducted opera world premières of Sven-David Sandström, Paula af Malmborg Ward, Daniel Nelson, Marie Samuelsson and Moto Osada’s both chamber operas, Nordic Artists Management / Denmark VAT number: DK29514143 http://nordicartistsmanagement.com including the international success Four Nights of Dream. -

Detroit Symphony

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY DETROIT SYMPHONY Neeme Jarvi Music Director and Conductor Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg, Violinist Marilyn Mason, Organist Sunday Afternoon, February 10, 1991, at 4:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Sinfonia Antiqua Lawrence Rapchak Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 . Shostakovich Moderate Scherzo: allegro Passacaglia: andante, cadenza Burlesque: allegro con brio, presto Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg INTERMISSION Symphony No. 3 in C minor ("Organ") Saint-Saens Adagio, allegro moderato, poco adagio Allegro moderato, presto, maestoso Marilyn Mason The piano heard in this concert is a Steinway available from Hammell Music, Inc., Livonia. Activities of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra are supported by the City of Detroit Council of the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Michigan Council for the Arts. London, RCA, and Mercury Records. For the convenience of our patrons, the box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for purchase of tickets to upcoming Musical Society concerts. Twenty-first Concert of the 112th Season 112th Annual Choral Union Series Program Notes Sinfonia Antiqua LAWRENCE RAPCHAK (b. 1951) hese are the first performances (this one in Ann Arbor and three in Detroit) of Lawrence Rapchak's Sinfonia Antiqua. The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, threeT oboes, English horn, clarinet, two bass clarinets, three bassoons, contrabassoon, four offstage horns, three trumpets, three trom bones, tuba, timpani, a large percussion bat tery managed by four players, harp, celesta, and strings. Lawrence Rapchak was born in Ham- mond, Indiana, and studied at the Cleveland Institute of Music. His composition teachers include Donald Erb, Marcel Dick, and Leonardo Balada; he has also studied conduct ing with James Levine. -

June 2008 Vol 46 No 2

Official Publication of the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians VOLUME 46 NO. 2 Online Edition June 2008 Fifty Years and Counting by Laura Ross, ICSOM Secretary t is important to pass along our memories about the formation fruits of my labor appear below. Jerome Wigler from the and advancement of our orchestras, for orchestra histories can Philadelphia Orchestra relates the history of his orchestra’s struggles, Ireveal a great deal. Just take a look at our collective bargaining his direct involvement in those efforts, and his early involvement with agreements—between the lines they document many instances of ICSOM. Frances Darger of the Utah Symphony responded to me improvements and abuses that explain what might otherwise remain directly about her 65 years of experience. Jane Little reveals war puzzling. I suspect there are a great many stories attached to CBA stories about touring as a charter member of the Atlanta Symphony. clauses that would either entertain or horrify a listener. Phil Blum explains how much auditions have changed since he joined the Chicago Symphony. Harriet Risk Woldt, who retires from the While I’ve been “through the wars” with my own orchestra, the Fort Worth Symphony at the end of this season, relates some Nashville Symphony, it’s only been for 24 years of the orchestra’s unusual memories of her years as a musician. Richard Kelley joined 62-year history. I believe it’s important to tell our story to each new his father in the Los Angeles Philharmonic and speaks of his member that joins the orchestra, not only so they understand where experiences under various music directors over the years. -

Week 12 2016–17 Season Prokofiev Weinberg Tchaikovsky

2016–17 season andris nelsons music director week 12 prokofiev weinberg tchaikovsky season sponsors seiji ozawa music director laureate bernard haitink conductor emeritus lead sponsor supporting sponsor thomas adès artistic partner Robert McCloskey, Drawing for Make Way for Ducklings (“There they “Make Way for Ducklings: The Art of Robert McCloskey” is organized by With support from the Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf waded ashore and waddled along till they came to the highway.”), The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, Amherst, Massachusetts. Exhibition Fund and the Patricia B. Jacoby Exhibition Fund. 1941. Graphite on paper. Courtesy of The May Massee Collection, Emporia The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Media sponsor is State University Special Collections and Archives, Emporia State University. presentation is made possible by Table of Contents | Week 12 7 bso news 1 7 on display in symphony hall 18 bso music director andris nelsons 2 0 the boston symphony orchestra 23 a case for quality by gerald elias 3 0 this week’s program Notes on the Program 32 The Program in Brief… 33 Sergei Prokofiev 41 Mieczys´law Weinberg 49 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky 57 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 63 Juanjo Mena 65 Gidon Kremer 7 0 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 8 3 symphony hall information the friday preview on january 20 is given by harlow robinson of northeastern university. program copyright ©2017 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo by Chris Lee cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617) 266-1492 bso.org andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate thomas adès, deborah and philip edmundson artistic partner 136th season, 2016–2017 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. -

Detroit Symphony Orchestra

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Detroit Symphony Orchestra GUNTHER HERBIG Music Director and Conductor HEINRICH SCHIFF, Cellist SUNDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 2, 1986, AT 4:00 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Ritual and Incantations ........................................ HALE SMITH Cello Concerto in D minor .......................................... LALO Lento, allegro maestoso Intermezzo: andantino con moto Andante, allegro vivace HEINRICH SCHIFF, Cellist INTERMISSION Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 97 ("Rhenish") ............. SCHUMANN Lebhaft Scherzo: sehr massig Nicht schnell Feierlich Lebhaft Detroit Symphony: London and Mercury Records. Cunther Herbig: Vox Records. Heinrich Schiff: Phonogram, EMI/Electrola, Deutsche Grammophon, Philips, and Amadeo Records. Activities of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra are made possible with the support of the State of Michigan, through funds from the Michigan Council for the Arts, and through funding from the City of Detroit. Fifty-seventh Concert of the 107th Season ' 107th Annual Choral Union Series PROGRAM NOTES by MICHAEL FLEMING Ritual and Incantations ........................................ HALE SMITH (b. 1925) Hale Smith was born in Cleveland, where he studied piano with Dorothy Price and composition with Marcel Dick at the Cleveland Institute of Music. In 1958 he moved to New York, where he worked as a music editor for several publishers, arranged for jazz groups, and composed. In 1969 he became advisor to the Black Music Center at Indiana University, and the next year joined the faculty of the University of Connecticut, from which he retired in 1984 with the title of professor emeritus. His major orchestral works include Orchestral Set (1952, revised 1968), Contours (1961), Ritual and Incantations (1974), and Innerjlexions (1977).