C:\Virginia's Veranda\Doll Article\Article.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atas Do V Congresso Português De Demografia

Atas do V Congresso Português de Demografia ISBN: 978-989-97935-3-8 Orgs: Maria Filomena Mendes Jorge Malheiros Susana Clemente Maria Isabel Baptista Sónia Pintassilgo Filipe Ribeiro Lídia P. Tomé Stella Bettencourt da Câmara V Congresso Português de Demografia Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian 6 e 7 de outubro de 2016 Conselho científico – Livro de Atas Alina Esteves (IGOT-UL) Ana Romão (Acad. Militar) Fernanda Sousa (FE-UP) Isabel Tiago de Oliveira (ISCTE-IUL) José Carlos Laranjo Marques (CICS.NOVA.IPLeiria) José Gonçalves Dias (ISCTE-IUL) José Rebelo (ESCE-IPS) Maria da Graça Magalhães (INE) Maria João Guardado Moreira (ESE-IPCB) Paulo Matos (FCSH-UNL) Paulo Nossa (ICS-UM) Teresa Rodrigues (FCSH-UNL) Livro de Atas 2 V Congresso Português de Demografia Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian 6 e 7 de outubro de 2016 Nota Introdutória Com a realização do V Congresso Português de Demografia, a Associação Portuguesa de Demografia (APD) pretendeu constituir um fórum de reflexão e debate privilegiado relativamente a todas as questões demográficas que marcam a atualidade, reunindo contributos de investigadores nacionais e estrangeiros de todas as áreas científicas para a disseminação do conhecimento demográfico. Congregando resultados e experiências de todos os que, nas suas funções quotidianas, se debruçam sobre os problemas demográficos contemporâneos, promoveu-se o intercâmbio não apenas científico mas também técnico com vista ao conhecimento aprofundado da realidade demográfica portuguesa, de modo a melhor (re)pensar e intervir em termos de futuro (de modo prospetivo). Neste sentido, este livro publica as atas do V Congresso Português de Demografia que decorreu na Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian de 6 a 7 de outubro de 2016, organizado pela Associação Portuguesa de Demografia (APD), em parceria com o Centro Interdisciplinar de História, Culturas e Sociedades (CIDEHUS) da Universidade de Évora, sob o tema A crise demográfica. -

Some Pages from the Book

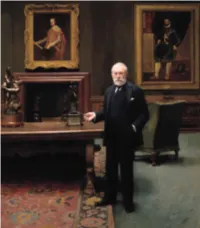

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

Tv Pg 5 04-04.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, April 4, 2008 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle FUN BY THE NUM B ERS will have you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, column and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESD A Y ’S SATURDAY EVENING APRIL 5, 2008 SUNDAY EVENING APRIL 6, 2008 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone The First 48: Stray Bullet; The First 48 Body rolled in The Sopranos (TVMA) (:18) The First 48 (TVPG) (:18) The First 48: Stray Bul- “The Godfather” (‘72, Drama) A decorated veteran takes over control of his family’s criminal empire from “The Godfather” (‘72) Ma- 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E his ailing father as new threats and old enemies conspire to destroy them. (R) fia family life. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

GB Middle, High Top State in Science Olympiad

A W A R D ● W I N N I N G jmillers.com 934-6200 Gulf Breeze ● Pensacola ● Destin 50 ¢ April 10, 2008 Ryan Roose shows the robot GB Middle, High he built for Science page4A Olympiad competition. top state in Both the Gulf Breeze Middle and High Schools will Community Life Center pets Science Olympiad compete at are blessed. nationals in new for the schools, there are the next level. Although his Washington, BY FRANKLIN HAYES some newcomers to the team machine suffered a mechanical PAG E D.C. Gulf Breeze News 1D [email protected] who are excited to prove their failure and his team placed 16th, worth against the nation’s very Roose is optimistic that his con- Whether it’s building func- best. traption can still be a dangerous ■ Surfers tional robots or identi- Like the infamous Dr. competitor. rescue fying samples of Frankenstein, Ryan Roose “If that hadn't happened, pair from igneous rock, Gulf toiled in his garage, combin- we would have won first or Breeze high and middle ing parts from defunct second place,” Roose said in Gulf school students are up machines to build the compet- reference to the Robot ■ Beach Ball to the challenge and itive robot he used in state Ramble event, where partici- is April 25 their talents are taking competition last month. A pants design and build them to compete among power window motor was robots to perform simple the nation’s best in used for torque and a rubber tasks. Science Olympiad. window cleaner was incorpo- Roose added that through Students from both rated to pick up index cards. -

Neonaticide: When the Bough Breaks and the Cradle Falls

Buffalo Law Review Volume 52 Number 2 Article 7 4-1-2004 Neonaticide: When the Bough Breaks and the Cradle Falls Shannon Farley University at Buffalo School of Law (Student) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Shannon Farley, Neonaticide: When the Bough Breaks and the Cradle Falls, 52 Buff. L. Rev. 597 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol52/iss2/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT Neonaticide: When the Bough Breaks and the Cradle Falls SHANNON FARLEYt INTRODUCTION On December 17, 1990, twenty-year-old Stephanie Wernick was in her dormitory bathroom tending to bleeding that she attributed to an unusually heavy menstrual pe- riod.' Jeanette, a girl living on Stephanie's dormitory floor, and her friend Laura, were in the hallway outside the bath- room when they heard what they thought was a baby's cry! The girls rushed into the bathroom and immediately noticed a pool of blood underneath the stall door at Stepha- nie's feet. Stephanie stated to the girls that she was fine t J.D. Candidate, State University of New York at Buffalo, 2004; B.A., State University of New York at Geneseo, 2001. I would like to thank especially my parents for all of their encouragement and support in the writing of this article and in my many other law school endeavors. -

William Penn's Chair and George

WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 by Justina Catherine Barrett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2005 Copyright 2005 Justina Catherine Barrett All rights reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1426010 Copyright 2005 by Barrett, Justina Catherine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1426010 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 By Justina Catherine Barrett Approved: _______ Pauline K. Eversmann, M. Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: J. -

CONCERNS ABOUT CHILD CARE Bill Muehlenberg Updated January 2009

CONCERNS ABOUT CHILD CARE Bill Muehlenberg Updated January 2009 Introduction I. Day care can be harmful to children II. Quality in day care III. Preference for home IV. Choice for women V. Recommendations Conclusion Introduction Modern life is full of pressures which were not around just several decades ago. Today the battle to pay off the family home and meet other financial needs is becoming increasingly more difficult. A single wage is often not sufficient. As a result more and more families are relying on two incomes to get them through. The need for out of home child care has therefore risen markedly. Moreover, the large increase in the number of single parents has also meant a greater demand for formal child care. With over $1.5 billion a year spent on child care by Australian Governments, child care is big business. And with over 600,000 children involved, it affects a lot of people.1 There is no denying that child care is a growth industry. Indeed, Commonwealth spending alone has risen 160 per cent between 1991 and 2001. In 2001 dollars it grew from $573 million to $1,490 million.2 But with the growth there have been questions raised. Concerns about child care are being expressed from a number of quarters. How does parental absence affect the child? With growing numbers of children being raised by strangers, what effects will this have on society in the near future? It is important that these questions and concerns are addressed before more growth takes place. This paper will examine some of these considerations. -

Claimed Studios Self Reliance Music 779

I / * A~V &-2'5:~J~)0 BART CLAHI I.t PT. BT I5'HER "'XEAXBKRS A%9 . AFi&Lkz.TKB 'GMIG'GCIKXIKS 'I . K IUOF IH I tt J It, I I" I, I ,I I I 681 P U B L I S H E R P1NK FLOWER MUS1C PINK FOLDER MUSIC PUBLISH1NG PINK GARDENIA MUSIC PINK HAT MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PINK 1NK MUSIC PINK 1S MELON PUBL1SHING PINK LAVA PINK LION MUSIC PINK NOTES MUS1C PUBLISHING PINK PANNA MUSIC PUBLISHING P1NK PANTHER MUSIC PINK PASSION MUZICK PINK PEN PUBLISHZNG PINK PET MUSIC PINK PLANET PINK POCKETS PUBLISHING PINK RAMBLER MUSIC PINK REVOLVER PINK ROCK PINK SAFFIRE MUSIC PINK SHOES PRODUCTIONS PINK SLIP PUBLISHING PINK SOUNDS MUSIC PINK SUEDE MUSIC PINK SUGAR PINK TENNiS SHOES PRODUCTIONS PiNK TOWEL MUSIC PINK TOWER MUSIC PINK TRAX PINKARD AND PZNKARD MUSIC PINKER TONES PINKKITTI PUBLISH1NG PINKKNEE PUBLISH1NG COMPANY PINKY AND THE BRI MUSIC PINKY FOR THE MINGE PINKY TOES MUSIC P1NKY UNDERGROUND PINKYS PLAYHOUSE PZNN PEAT PRODUCTIONS PINNA PUBLISHING PINNACLE HDUSE PUBLISHING PINOT AURORA PINPOINT HITS PINS AND NEEDLES 1N COGNITO PINSPOTTER MUSIC ZNC PZNSTR1PE CRAWDADDY MUSIC PINT PUBLISHING PINTCH HARD PUBLISHING PINTERNET PUBLZSH1NG P1NTOLOGY PUBLISHING PZO MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PION PIONEER ARTISTS MUSIC P10TR BAL MUSIC PIOUS PUBLISHING PIP'S PUBLISHING PIPCOE MUSIC PIPE DREAMER PUBLISHING PIPE MANIC P1PE MUSIC INTERNATIONAL PIPE OF LIFE PUBLISHING P1PE PICTURES PUBLISHING 882 P U B L I S H E R PIPERMAN PUBLISHING P1PEY MIPEY PUBLISHING CO PIPFIRD MUSIC PIPIN HOT PIRANA NIGAHS MUSIC PIRANAHS ON WAX PIRANHA NOSE PUBL1SHING P1RATA MUSIC PIRHANA GIRL PRODUCTIONS PIRiN -

The Union and Journal: Vol. 25, No. 33

BE TBUE, AND FAITHFUL, AHD VALIAKT FOB TBI PUBLIC LIBEBTIES, NUMBER 33. VOLUME XXV. BIDDEFORD, ME., FRIDAY MORNING, AUGUST 6, 1869. the and the Tht JM the on the floor, he darted forward grave, sphere of it is the whole own That I will to In the first »f fell heavily Times were dull and business even enough for his consumption. explain you. place, poor, there U in this laid his hand on the door of the clock- of Woman's want en- Peter White's winter he worked for Mr. Stevens at cot- not another of land A* IUM LNHID. and region humanity. anb though it was earl)- spring. spot is he who would £bt 3ition XV. out for dollars section of the that no—wi the case. But no human could open emy cruelly lift her out Journal first after the deed of his ting lumber, twenty-five oountry Of all the little bird* that lira ap la Um traa, power n riuuh) raui »» goft having pot merry mi iouin object natural one does. and when came he was which this cam Um and a of her and would to rerene land, was to hunt some kind of work. |H-r month; spring advantages And I from ayoaaaora chaetaut, it. Joe was it inside with death- sphere try the up I can Tines little that deareet U to Bia, holding J". £. BUTLUR, Tk* CUmr fwMH. have to on to his land hare ray peas and up The preUlest gentleman nature If he had been a mechanic he ready go again. -

United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-1963 United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War Phyllis Korzilius Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Korzilius, Phyllis, "United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War" (1963). Master's Theses. 3813. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3813 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNITED vlE SERVE Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War by Phyllis Korzilius A thesis presented to the ,1 •Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June, 1963 PREFACE In high school and college most of my study in the Civil War period centered in the great battles, generals, political figures, and national events that marked the American scene between 1861 and 1865. Because the courses were of a broad survey type, it would have been presumptuous to expect any special attention to such is sues as the role of women in the war. However, a probe of the more common or personal aspects of the "era of conflict" provides a deeper insight of the era as well as more knowledge. -

Board of Commissioners

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS ANDREW H. GREEN, THOMAS C. FIELDS, ROBERT J. DILLON, PETER B. SWEENY, Resigned, November, 1871. HENRY HILTON, (L 22d (I tL HENRY G. STEBBINS, Appointed 22d " L ( FREDERICK E. CHURCH, L (6 61 << ANDREW H. GREEN, ROBERT J. DILLON, THOMAS C. FIELDS, FREDERICK E. CHURCH, , HENRY G. STEBBINS, . Resigned, 28th May, 1872. FRED. LAW OLMSTED, . Appointed, " LL I( President. PETER B. SWEENY, . To 22d November, 1871. LL I1 HENRY G. STEBBINS, . From " Vice-President. HENRY HILTON, . To 22d November, 1871. (Vacancy.) From " L L LC Treasurer. HENRY HILTON, . To 22d November, 1871. LC I L HENRY G. STEBBINS, . From " Conzptroller of Accounts. GE0RG.E M. VAN NORT. President and Treasurer. HENRY G. STEBBINS, . To 28th May, 1872. Il FRED. LAW OLMSTED, . From " " Vice-President. ANDREW H. GREEN, . From 15th May, 1872. Clerk to the Board. E. P. BARKER, . From 30th January to 26th June. 1 F. W. WHITTEMORE, . From 26th June to 10th July. \, I Secretary. I F. W. WHITTEMORE, . Office constituted 10th July, 1872. 8 I CONTENTS. Change of Administration-Reduction of Force-Contraction of Fields of Labor-Liabilities, November, 1871-Involved Accounts-Funds raised for one class of work applied to another- Plans Suspended-Location of Buildings for orMetropolitan Museum of Art and American Mn- seum of Natural History. ............................................................. PAt Union Spuare-Modification of its Plan-Statistics of Use-Projected Improvements.. ........ PAGE 4 111.-THE CENTRALPARK : Its Cost-Indications of its Value-the Increased Value of Real Estate-Statement of Valuations of Real Estate adjoining the Park for a series of years-The Rate of Taxes for 1871.