An Analysis of Economic Trends Beyond New World Wine Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish Wine & Extra Virgin Olive Oil Selection

Spanish Wine & Extra Virgin Olive Oil Selection ORIGIN ORIGIN FOOBESPAIN INTERNATIONAL trajectory has always been marked by a continuous learning of different cultures and international markets and the search for wine producers with an interesting and suitable portfolio for these markets. The major premise of FOOBESPAIN INTERNATIONAL is to harness this market knowledge to offer a wide range of innovative wine brands tailored to our costumers needs. CONTACT BUSINESS PHILOSOPHY FOOBESPAIN INTERNACIONAL devotes its business to commercial representation of [email protected] wineries at international and national level. Foobespain has a long marketing and sale +34 926 513 167 of wine with high added value which, in turn, great value for the price. FOOBESPAIN Avenida de la Mancha, 80 6º C already has an experience of more than 10 years as a commercial representative of 02008 Albacete - Spain wineries and currently exports more than 25 countries to international level. It also offers commercial and marketing support to its customers throughout the world. DEHESA DEL CARRIZAL Dehesa del Carrizal is a Vino de Pago, the highest category accord- ing The oldest grapevines of Cabernet Sauvignon have grown at Dehesa to Spanish wine law. It is a DOP (Denominación de Origen Protegida - del Carrizal since 1987. They were later joined by Syrah, Merlot. Protected Designation of Origin) reserved for those few wineries and The acid soils of the siliceous Mediterranean mountains, a humid vineyards which carry out the whole process -from the grape to the climate and 800 metres of altitude create the perfect particular micro bottle- within the limits of the Pago or estate. -

Varietal Appellation Region Glera/Bianchetta

varietal appellation region 14 prairie organic vodka, fever tree ginger glera/bianchetta veneto, Italy 13 | 52 beer,cucumber, lime merlot/incrocio manzoni veneto, Italy 13 | 52 14 prairie organic gin, rhubarb, lime, basil 14 brooklyn gin, foro dry vermouth, melon de bourgogne 2016 loire, france 10 | 40 bigallet thym liqueur, lemon torrontes 2016 salta, argentina 10 | 40 14 albarino 2015 rias baixas, spain 12 | 48 foro amaro, cointreau, aperol, prosecco, orange dry riesling 2015 finger lakes, new york 13 | 52 14 pinot grigio 2016 alto-adige, italy 14 | 56 milagro tequila, jalapeno, lime, ancho chili salt chardonnay 2014 napa valley, california 14 | 56 14 sauvignon blanc 2015 loire, france 16 | 64 mount gay silver rum, beet, lime 14 calvados, bulleit bourbon, maple syrup, angostura bitters, orange bitters gamay 2016 loire, france 10 | 40 grenache/syrah 2016 provence, france 14 | 56 spain 8 cabernet/merlot 2014 bordeaux, france 10 | 40 malbec 2013 mendoza, argentina 13 | 52 illinois 8 grenache 2014 rhone, france 13 | 52 california 8 sangiovese 2014 tuscany, Italy 14 | 56 montreal 11 pinot noir 2013 central coast, california 16 | 64 massachusetts 10 cabernet sauvignon 2015 paso robles, california 16 | 64 Crafted to remove gluten pinot noir 2014 burgundy, france 17 | 68 massachusetts 7 new york 12 chardonnay/pinot noir NV new york 8 epernay, france 72 new york 9 pinot noir/chardonnay NV ay, france 90 england 10 2014 france 25 (750 ml) friulano 2011 friuli, Italy 38 gruner veltliner 2016 weinviertel, austria 40 france 30 (750 ml) sauvignon -

Walla Walla • Washington

Walla Walla • Washington MERLOT, BORDEAUX- STYLE RED BLENDS AND CABERNET SAUVIGNON FROM ONECANADA OF WALLA WALLA VALLEY’S FOUNDING WINERIES WALLA WALLA VALLEY HERITAGE COMMITMENT TO SUSTAINABILITY • Winemaker Casey McClellan and his father planted the • Sustainability is an important focus on both a local and Seven Hills Old Blocks in 1980 personal level N • Established in 1988 as the fifth winery in Walla Walla • Currently certified by LIVE (Low Input Viticulture & Valley, Seven Hills Winery shaped the varietal focus of the Enology) & Salmon Safe appellation. 2018 marks the winery’s 30th anniversary FOCUS ON QUALITY OLD WORLD WINE STYLE • An established reputation over the past three decades and SEATTLE • Wines known for varietal typicity a proven record of high scores • Restrained oak and balanced acidity combine to create • Long-standing relationships with the Northwest’s most y structure and gracefulnesse respected vineyards l N l WASHINGTON a V a WINEGROWING PHILOSOPHY i C b o lu m m e b u i g a l R Since 1988, Seven Hills Winery has worked to cultivate n i v o e a r C IDAHO R RED MOUNTAIN long-term relationships with the oldest and most e Ciel du Cheval d a Vineyard respected growers in the Northwest. The winery’s c s WALLA WALLA VALLEY a HORSE HEAVEN HILLS C exceptional vineyard program focuses on Walla Walla Valley McClellan Estate Seven Hills Old Blocks Vineyard and Red Mountain and includes the estate-designated iver ia R lumb Co OREGON Seven Hills Old Blocks. PORTLAND Pacific Ocean CASEY McCLELLAN, WINEMAKER As a founder of Seven Hills Winery, Casey McClellan has served as winemaker since the winery’s inception. -

September 2000 Edition

D O C U M E N T A T I O N AUSTRIAN WINE SEPTEMBER 2000 EDITION AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD AT: WWW.AUSTRIAN.WINE.CO.AT DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition Foreword One of the most important responsibilities of the Austrian Wine Marketing Board is to clearly present current data concerning the wine industry. The present documentation contains not only all the currently available facts but also presents long-term developmental trends in special areas. In addition, we have compiled important background information in abbreviated form. At this point we would like to express our thanks to all the persons and authorities who have provided us with documents and personal information and thus have made an important contribution to the creation of this documentation. In particular, we have received energetic support from the men and women of the Federal Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management, the Austrian Central Statistical Office, the Chamber of Agriculture and the Economic Research Institute. This documentation was prepared by Andrea Magrutsch / Marketing Assistant Michael Thurner / Event Marketing Thomas Klinger / PR and Promotion Brigitte Pokorny / Marketing Germany Bertold Salomon / Manager 2 DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Austria – The Wine Country 1.1 Austria’s Wine-growing Areas and Regions 1.2 Grape Varieties in Austria 1.2.1 Breakdown by Area in Percentages 1.2.2 Grape Varieties – A Brief Description 1.2.3 Development of the Area under Cultivation 1.3 The Grape Varieties and Their Origins 1.4 The 1999 Vintage 1.5 Short Characterisation of the 1998-1960 Vintages 1.6 Assessment of the 1999-1990 Vintages 2. -

An Exploratory Research of the Potential Strategic Benefits of Specialising in Riesling Grape: a Case Study from the Niagara Wine Region

Advances in Economics and Business 4(10): 515-524, 2016 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/aeb.2016.041001 An Exploratory Research of the Potential Strategic Benefits of Specialising in Riesling Grape: A Case Study from the Niagara Wine Region Federico Topolansky Barbe1,*, Magdalena Gonzalez Triay2, Andrea Fujarczuc1 1School of Business and Entrepreneurship, Royal Agricultural University, UK 2Marketing Department, University of Gloucestershire, UK Copyright©2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The main purpose of this paper is to evaluate there is no research that has looked at the potential benefits the current business strategy of the Niagara wine region and of specialising in any grape varietal including Riesling. This to explore the potential of the Niagara wine region to research will partially address this gap in knowledge by specialise in Riesling grape variety. Questionnaires were gaining a deeper understanding of the potential benefits from administered to a range of different types of experts with a adopting specialisation in Riesling. This study is relevant specialty in wine. Quantitative data from the Liquor Control because it may help to determine whether the Niagara Board of Ontario supplemented the core interviews. The industry is producing wine with the greatest possible results of this study indicate that differentiation through efficiency. specialisation is the best strategy to develop the Niagara The specific objectives of this study are the following. wine region. However, the structure of the wine industry First, to evaluate the potential of the Niagara wine region to encourages wineries to produce a vast array of grape specialise in Riesling grape. -

Celebrity Cruises Proudly Presents Our Extensive Selection of Fine Wines

Celebrity Cruises proudly presents our extensive selection of fine wines, thoughtfully designed to match our globally influenced blend of classic and contemporary cuisine. Our wine list was created to please everyone from the novice wine drinker to the most ardent enthusiast and features over 300 selections. Each wine was carefully reviewed by Celebrity’s team of wine professionals and was selected for its superior quality. We know you share our passion for fine wines and we hope you enjoy your wine experience on Celebrity Cruises. Let our expertly trained sommeliers help guide you on your wine explorations and assist you with any special requests. Cheers! SIGNATURE COCKTAILS $14 BOURBON AND PEACHES MAKER’S MARK BOURBON | PEACH | SIMPLE | LEMON SPICY PASSION KETEL ONE VODKA | PASSION FRUIT | LIME | JALAPEÑO | MINT ULTRAVIOLET BOMBAY SAPHIRE GIN | CRÈME DE VIOLETTE LIQUEUR | SIMPLE FRESH FROM TOKYO GREY GOOSE VODKA | SIMPLE | YUZU | CUCUMBER | BASIL VANILLA MOJITO ZACAPA® 23 RUM | BARREL-AGED CACHAÇA | LIME | VANILLA WANDERING SCOTSMAN BULLEIT RYE | DEMERARA | SCOTCH RINSE BY THE GLASS BUBBLY Brut, Montaudon, Champagne ................................................................................................................................................... 15 Brut, PerrierJouët, ‘Grand Brut,’ Epernay, Champagne .................................................................................................................. 20 Brut Rosè, Domaine Carneros Carneros, California ...................................................................................................................... -

JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3

Book Reviews 423 JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3. Written by Christina Wise and Jason Wise, Produced by Forgotten Man Films, Distributed by Samuel Goldwyn Films, 2018; 1 h 18 min. This is the third in a trilogy of documentaries about the wine world from Jason Wise. The first—Somm, a marvelous film which I reviewed for this Journal in 2013 (Stavins, 2013)–followed a group of four thirty-something sommeliers as they prepared for the exam that would permit them to join the Court of Master Sommeliers, the pinnacle of the profession, a level achieved by only 200 people glob- ally over half a century. The second in the series—Somm: Into the Bottle—provided an exploration of the many elements that go into producing a bottle of wine. And the third—Somm 3—unites its predecessors by combining information and evocative scenes with a genuine dramatic arc, which may not have you on pins and needles as the first film did, but nevertheless provides what is needed to create a film that should not be missed by oenophiles, and many others for that matter. Before going further, I must take note of some unfortunate, even tragic events that have recently involved the segment of the wine industry—sommeliers—featured in this and the previous films in the series. Five years after the original Somm was released, a cheating scandal rocked the Court of Master Sommeliers, when the results of the tasting portion of the 2018 exam were invalidated because a proctor had disclosed confidential test information the day of the exam. -

Post-Fermentation Clarification: Wine Fining Process

Post-Fermentation Clarification: Wine Fining Process A Major Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute In partial fulfillments of the requirements for the Chemical Engineering Bachelor of Science Degree Sponsored by: Zoll Cellars 110 Old Mill Rd. Shrewsbury, MA Submitted by: Allison Corriveau _______________________________________ Lindsey Wilson _______________________________________ Date: April 30, 2015 _______________________________________ Professor Stephen J. Kmiotek This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, please see http://www.wpi.edu/academics/ugradstudies/project-learning.html Abstract The sponsor, Zoll Cellars, is seeking to improve their current post-fermentation process. Fining is a post-fermentation process used to clarify wine. This paper discusses several commonly used fining agents including: Bentonite, Chitosan and Kieselsol, and gelatin and Kieselsol. The following tests were conducted to compare the fining agents: visual clarity, mass change due to racking, pH, and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Bentonite was an F. Chitosan and Kieselsol were also successful with a wait time before racking of at least 24 hours. Gelatin and Kieselsol are not recommended for use at Zoll Cellars because gelatin easily over stripped the wine of important flavor compounds. i Acknowledgements We would like to thank our advisor, Professor Stephen J. Kmiotek, for his essential guidance and support. This project would not have been a success without you. We really appreciated how readily available you were to help us with any setbacks or problems that arose. -

Grape Growing

GRAPE GROWING The Winegrower or Viticulturist The Winegrower’s Craft into wine. Today, one person may fill both • In summer, the winegrower does leaf roles, or frequently a winery will employ a thinning, removing excess foliage to • Decades ago, winegrowers learned their person for each role. expose the flower sets, and green craft from previous generations, and they pruning, taking off extra bunches, to rarely tasted with other winemakers or control the vine’s yields and to ensure explored beyond their village. The Winegrower’s Tasks quality fruit is produced. Winegrowers continue treatments, eliminate weeds and • In winter, the winegrower begins pruning • Today’s winegrowers have advanced trim vines to expose fruit for maximum and this starts the vegetative cycle of the degrees in enology and agricultural ripening. Winegrowers control birds with vine. He or she will take vine cuttings for sciences, and they use knowledge of soil netting and automated cannons. chemistry, geology, climate conditions and indoor grafting onto rootstocks which are plant heredity to grow grapes that best planted as new vines in the spring, a year • In fall, as grapes ripen, sugar levels express their vineyards. later. The winegrower turns the soil to and color increases as acidity drops. aerate the base of the vines. The winegrower checks sugar levels • Many of today’s winegrowers are continuously to determine when to begin influenced by different wines from around • In spring, the winegrower removes the picking, a critical decision for the wine. the world and have worked a stagé (an mounds of earth piled against the base In many areas, the risk of rain, hail or apprenticeship of a few months or a of the vines to protect against frost. -

Federal Register/Vol. 77, No. 56/Thursday, March 22, 2012/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 56 / Thursday, March 22, 2012 / Rules and Regulations 16671 litigation, establish clear legal DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY • The United States; standards, and reduce burden. • A State; Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade • Two or no more than three States Executive Order 13563 Bureau which are all contiguous; The Department of State has • A county; considered this rule in light of 27 CFR Part 4 • Two or no more than three counties Executive Order 13563, dated January in the same State; or [Docket No. TTB–2010–0007; T.D. TTB–101; • A viticultural area as defined in 18, 2011, and affirms that this regulation Re: Notice No. 110] is consistent with the guidance therein. § 4.25(e). RIN 1513–AB58 Section 4.25(b)(1) states that an Executive Order 13175 American wine is entitled to an Labeling Imported Wines With The Department has determined that appellation of origin other than a Multistate Appellations this rulemaking will not have tribal multicounty or multistate appellation, implications, will not impose AGENCY: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and or a viticultural area, if, among other substantial direct compliance costs on Trade Bureau, Treasury. requirements, at least 75 percent of the Indian tribal governments, and will not ACTION: Final rule; Treasury decision. wine is derived from fruit or agricultural preempt tribal law. Accordingly, products grown in the appellation area Executive Order 13175 does not apply SUMMARY: The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax indicated. Use of an appellation of to this rulemaking. and Trade Bureau is amending the wine origin comprising two or no more than labeling regulations to allow the three States which are all contiguous is Paperwork Reduction Act labeling of imported wines with allowed under § 4.25(d) if: This rule does not impose any new multistate appellations of origin. -

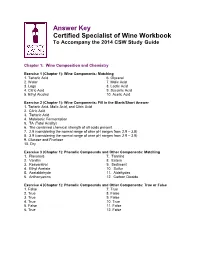

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

Old World, New World, Third World? Reconceptualising the Worlds of Wine

Journal of Wine Research, 2010, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 57–75 Old World, New World, Third World? Reconceptualising the Worlds of Wine GLENN BANKS and JOHN OVERTON Original manuscript received, 08 April 2009 Revised manuscript received, 18 November 2009 ABSTRACT This paper argues that existing categories defining the geography of the world’s wine industry, principally the Old World/New World dichotomy, are flawed. Not only do they fail to represent adequately the complexity of production and marketing in those two broad regions but also, crucially, they do not acknowledge the significant and rapidly expanding production and consumption of wine in ‘Third World’ developing countries. Rather than argue for the addition of a ‘Third World’ category, we instead use the lens of recent work on globalisation to argue that such production requires us to re-examine the dichotomous Old/New distinction which structures much of the thinking around the global wine industry. It also requires us to more closely link changes in patterns of global wine consumption with developments in global production. Changing geographies of wine production have been driven, to a large extent, by the rapid expansion of both local wealthy elites and burgeoning middle classes in countries such as China and India. This has resulted in the development of local wineries, large and small, throughout the developing world. It has also seen new flows of investment both from established wine regions to these new sites of production and from companies and individuals in the developing world who have invested in established wine regions, whether in France or Australia.