If\{TET?F\{ a Tiof\{ at HAIKU Cotvvef\{Tiof\{ MASAOKASHIKI If\{TET?F\{ a Tiof\{ at HAIKU AWAT?DS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haiku Attunement & the “Aha” Moment

Special Article Haiku Attunement & the “Aha” Moment By Edward Levinson Author Edward Levinson As a photographer and writer living, working, and creating in Japan spring rain for 40 years, I like to think I know it well. However, since I am not an washing heart academic, the way I understand and interpret the culture is spirit’s kiss intrinsically visual. Smells and sounds also play a big part in creating my experiences and memories. In essence, my relationship with Later this haiku certainly surprised a Japanese TV reporter who Japan is conducted making use of all the senses. And this is the was covering a “Haiku in English” meeting in Tokyo where I read it. perfect starting point for composing haiku. Later it appeared on the evening news, an odd place to share my Attunement to one’s surroundings is important when making inner life. photographs, both as art and for my editorial projects on Japanese PHOTO 1: Author @Edward Levinson culture and travel. The power of the senses influences my essays and poetry as well. In haiku, with its short three-line form, the key to success is to capture and share the sensual nature of life, both physical and philosophical. For me, the so-called “aha” moment is the main ingredient for making a meaningful haiku. People often comment that my photos and haiku create a feeling of nostalgia. An accomplished Japanese poet and friend living in Hokkaido, Noriko Nagaya, excitedly telephoned me one morning after reading my haiku book. Her insight was that my haiku visions were similar to the way I must see at the exact moment I take a photo. -

Soseki's Botchan Dango ' Label Tamanoyu Kaminoyu Yojyoyu , The

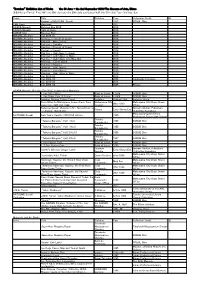

"Botchan" Exhibition List of Works the 30 June - the 2nd September 2018/The Museum of Arts, Ehime ※Exhibition Period First Half: the 30th Jun sat.-the 29th July sun/Latter Half: the 31th July Tue.- 2nd Sep. Sun Artist Title Piblisher Year Collection Credit ※ Portrait of NATSUME Soseki 1912 SOBUE Shin UME Kayo Botchans' 2017 ASADA Masashi Botchan Eye 2018' 2018 ASADA Masashi Cats at Dogo 2018 SOBUE Shin Botchan Bon' 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2018-01 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - White Heron 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Camellia 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi-Neko in Green 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko at Night 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko with Blue Sky 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Turner Island 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Pegasus 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 1 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 2 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko in White 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2013-03 2013 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2002-02 2002 Takahashi Collection MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2014-02 2014 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2006-04 2006 Private ASADA Masashi 'Botchan Eye 2018' Collaboration Materials 1 Yen Bill (2 Bills) Bank of Japan c.1916 SOBUE Shin 1 Yen Silver Coin (3 Coins) Bank of Japan c.1906 SOBUE Shin Iyotetsu Railway Ticket (Copy) Iyotetsu Original:1899 Iyotetsu Group From Mitsu to Matsuyama, Lower Class, Fare Matsuyama City Matsuyama City Dogo Onsen after 1950 3sen 5rin , 28th Oct.,1888 Tourism Office Natsume Soseki, Botchan 's Inn Yamashiroya is Iwanami Shoten, Publishers. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/97g9d23n Author Mewhinney, Matthew Stanhope Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki By Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alan Tansman, Chair Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Daniel C. O’Neill Professor Anne-Lise François Summer 2018 © 2018 Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney All Rights Reserved Abstract The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki by Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Tansman, Chair This dissertation examines the transformation of lyric thinking in Japanese literati (bunjin) culture from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. I examine four poet- painters associated with the Japanese literati tradition in the Edo (1603-1867) and Meiji (1867- 1912) periods: Yosa Buson (1716-83), Ema Saikō (1787-1861), Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) and Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916). Each artist fashions a lyric subjectivity constituted by the kinds of blending found in literati painting and poetry. I argue that each artist’s thoughts and feelings emerge in the tensions generated in the process of blending forms, genres, and the ideas (aesthetic, philosophical, social, cultural, and historical) that they carry with them. -

Shiki and Modernism

Anita Virgil JAPAN AND THE WEST: SHIKI AND MODERNISM Alone In the editorial department: Summer rain falling. Shiki 1 In the years between Issa’s death and Shiki’s birth, enormous change had wracked Japan politically, socially and culturally. At mid-19th century, after more than 200 years of isolation, Japan was torn by economic problems and beleaguered from without by foreigners seeking to open Japan to trade with the West. Her farmers and samurai were financially depleted, her merchants could not function without access to markets. Dissolute factions within the country jockeyed for dominance over the crumbling Tokugawa Shogunate to the extent that some Japanese called for restoration of the Emperor. The appearance of the Black Ships of Russia, England and America heightened the anxiety of an already troubled nation. Change was inevitable and necessary for the survival of Japan. With the arrival of Commodore Perry in Edo Bay in 1853, Japan was eventually forced into the modern world. It did not take long for the Japanese to recognize their defenselessness in the face of the military and technological superiority of the West. With dispatch, they sent emissaries abroad to obtain firsthand knowledge of their enemy, the “barbarians.” The result: the Japanese people were awash in a flood of ideas that conflicted with their ancient traditions. On September 17, 1867 in this time of ferment and cross-cultural exchange, Masaoka Tsunenori was born in Matusuyama on the island of Shikoku. (Later in his life, as was customary among Japanese poets, he adopted the name Shiki.) His father, Masaoka Hayata, was a samurai of lower rank who died of alcoholism. -

Revue Francophone De Haïku Janvier-Mars 2013 N°38

38 REVUE FRANCOPHONE DE HAÏKU JANVIER-MARS 2013 N°38 38 2 38 3 IL ÉTAIT UNE FOIS… MARTIGUES C hers adhérents et amis haijins, À l’entrée de l’hiver, ce numéro de GONG, épais et résonnant, devrait vous apporter un peu de chaleur et d’énergie. Soit que vous ayez participé au festival de Martigues et vous revivrez alors tous les moments forts de l’événe- ment. Soit que vous n’ayez pu vous y rendre et nous espérons alors que ce GONG, en majeure partie consacré au festival, le reflète fidèlement et vous associe aux découvertes, aux joies et aux surprises qu’il nous a offertes. U n peu différent des précédents, ce festival ? Oui, mais en quoi ? Tout d’abord parce qu’il était parrainé par le Consulat du Japon de Mar- seille. A noter que le Consul Général, Monsieur Sato, avait pris ses fonctions le 1er octobre et que notre festival a été sa première sortie officielle. Je ga- ge qu’il n’oubliera pas la soirée Japon, à laquelle il a assisté dans sa totalité. Ensuite, parce que nous avons bénéficié d’une contribution inestimable de la Mairie de Martigues qui a mis à notre disposition des salles équipées, des équipes techniques et qui a fait la promotion de notre festival par voie d’af- fiches et de flyers et réglé le protocole pour la visite de Monsieur le Consul Général du Japon. Enfin, parce que, du fait de notre ténacité et grâce à quelques précieuses ouvertures au Conseil Général, ainsi qu’un épais dossier bien ficelé – lequel a voyagé dans les services du Conseil Général ! – nous avons fini par obtenir la subvention à laquelle nous prétendions. -

Paul D. Talcott Independent Scholar the Spread of Market Mechanisms

Paul D. Talcott Mary Evelyn Tucker Independent Scholar Yale, Senior Lecturer and Senior Research Scholar The spread of market mechanisms in health care policy in Religion and ecology; Book Thomas Berry and the Arc of Japan and East Asia; the relationship between economic History (2019) development, democracy, and the introduction of market [email protected] principles into social insurance systems [email protected] Timothy J. Van Compernolle Amherst, Prof. of Japanese Wako Tawa The creative exchanges between literature and cinema in Amherst, Prof. of Asian Languages and Civilizations; interwar Japan Director of Language Study [email protected] Japanese grammar for learners of Japanese as a foreign language Floris van Swet [email protected] Northumbria, Postdoctoral Research Fellow Social and political consequences of attainder in early Elizabeth ten Grotenhuis Tokugawa Japan BU, Prof. Emerita for Japanese Art; [email protected] Received start-up grant to construct middle-school curriculum on immigration from China and Japan which she Elena Varshavskaya taught at Birches School Rhode Island School of Design, Senior Lecturer [email protected] ukiyo-e prints as historic documents [email protected] Sarah Thompson MFA, Curator of Japanese Art Alexander M. Vesey Japanese prints in the MFA collection, especially ukiyo-e Meiji Gakuin, Assoc. Prof. of Global & Transcultural Studies woodblock prints Early modern Japanese Buddhist social history [email protected] [email protected] R. Kenji Tierney James Keith Vincent SUNY New Paltz, Lecturer. of Anthropology BU, Assoc. Prof. of Japanese and Comparative Literature Sumo; Food; Globalization; Sports; The Body; Japan Natsume Soseki and Masaoka Shiki; haiku and the novel [email protected] [email protected] Maria Toyoda Louise E. -

Santoka's Shikoku

Santōka’s Shikoku An introduction to and translation of the opening sections of the Shikoku Henro Diary of Japanese free-verse haiku poet and itinerant Buddhist priest Taneda Santōka (1882-1940) Ronald S. Green, Coastal Carolina University Of the many literary figures associated with Shikoku, Japan and the Buddhist pilgrimage to the 88 temples around the perimeter of that island, Taneda Santōka is the most visible to pilgrims and the one most associated with their sentiments. According to the newspaper Asahi Shinbun, each year 150,000 people embark on the Shikoku pilgrimage by bus, train, automobile, bicycles, or walking. Among these, nearly all the foreign visitors make the journey on foot, spending weeks or months on the pilgrimage. Those walking are likely to encounter the most poetry steles (kuhi) that display the works of Taneda Santōka (1882-1940) and commemorate his life and pilgrimage in Shikoku. This is because some of the kuhi are located halfway up steep stairway ascents to temples or at entrances to narrow mountain paths, places Santōka loved. This paper introduces English readers to Santōka’s deep connection with Shikoku. This will become increasingly important as the Shikoku pilgrimage moves closer to becoming a UNESCO World Heritage site and the prefectures eventually achieve that goal. Santōka was an itinerant Buddhist priest, remembered mostly for his gentle nature that comes through to readers of his free-verse haiku. Santōka is also known for his fondness of Japanese sake, which eventually contributed to his death in Shikoku at the age of 58. Santōka lived at a time when Masaoka Shiki was innovating haiku by untying it from some of the classical rules that young poets were finding to be a hindrance to their expressions. -

Extending the Notion of Home Through the Language of Poetry

ASIATIC, VOLUME 4, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2010 Extending the Notion of Home Through the Language of Poetry David Farrah1 Kobe City University of Foreign Studies, Japan Abstract This essay will offer a personalised, critical consideration of how the notion of “home”, while remaining central to my vision as a poet, has evolved from the provincial to the international to the universal through the medium of landscape. It will accordingly ask the following question: how do we find a way to express ourselves through the features of a landscape we might not initially consider to be “home”, in the language of poetry? In answer to that question, the Japanese concept of “shakkei” or “borrowed landscape” will be explored as it relates to both literary history and the more contemporary concern for the expression and cultivation of the individual self. In particular, the technique of “ikedori”, or the “capturing alive” of a landscape will be examined. And finally, this essay will suggest that “shakkei” and poetry are much more than just metaphors for each other. Rather, they are organically and artistically linked mediums through which creative wonder is formalised, personalised and expressed. Keywords Landscape, gardening, poetry, shakkei, Japanese, expatriate, home But our native country is less an expanse of territory than a substance; it’s a rock or a soil or an aridity or a water or a light. It’s the place where our dreams materialize; it’s through that place that our dreams take on their proper form…. Dreaming beside the river, I gave my imagination to the water…. Gaston Bachelard, L’Eau et les Rêves. -

La Revue Du Haïku

La revue du haïku N° 48 – Décembre 2013 Association pour la promotion du haïku www.100pour100haiku.fr SOMMAIRE 1. Préambule par Christian Faure 5 2. « Kigo or not kigo ? » - texte issu d’un entretien avec Seegan MABESOONE 7 3. Le Haïku en mouvement au Japon depuis l’an 2000, texte de Katsuhiro HORIKI 12 4. “ Mon Kigo préféré ” 19 5. “ Les instants choisis ” 20 6. “ Les compositions des auteurs ” 24 Ploc¡ la revue du haïku Numéro réalisé par Christian Faure, Damien Gabriel 1. PRÉAMBULE Christian FAURE Un cycle se termine et un autre commence : voilà ce que nous enseigne le passage à l’année nouvelle. Quant au temps cyclique, il se révèle dans le haïku. La période du nouvel an reste le moment du renouvellement virginal (cf ploc 38 - kigos du renouveau), occasion pour s’interroger sur soi-même et se promettre de bonnes résolutions. Vous trouverez ici de nouvelles fenêtres sur le Japon sous formes d’interrogations : la composition sans kigo est-elle concevable (entretien avec Laurent Seegan Mabesoone) et le monde du haïku évolue-t-il (Katsuhiro Horikiri) ? Ensuite nous retrouverons les compositions de nos auteurs et leurs kigos préférés. Enfin, nous vous proposerons de composer deux haïkus maximum dans le rythme 575 pour le prochain numéro du « projet kigo » : - sur des mots de saison de l’hiver en relation avec les fêtes (noël, jour de l’an, la Saint-Sylvestre, le champagne, le premier vin [de l’année], les premières fois [Cf n°38 de Ploc –les kigos du renouveau, etc..) - et/ou des kigos libres de printemps. -

Shiki - Haiku Reformation

Shiki - Haiku Reformation Shiki Masaoka Was a Fighter and Radical Banned from Public Speaking at 15; Failed College by 1892 by Don Baird When studying Shiki (1867-1902), his Japan, and its relationship to the rest of the world, the Tokugawa policy of seclusion (known as sakoku) must be considered, as it not only barred nearly all international trade, it also forbade the Japanese to leave Japan. The Tokugawa period of isolation lasted some 200 years (1630s-1850s). This context forms an important basis of an old-world, some would say feudal, culture, and mindset stemming from such isolation. It is likewise important to remember that Shiki's grandfather, Ōhara Kanzan, was a Confucian scholar, Samurai, and Shiki's first teacher, who was a significant, influential aspect of Shiki's psychological foundation. Kanzan was outspoken and unwavering against the onset of western civilization: Kanzan was adamantly opposed to the new world of the Meji period. He refused, for example, to study any Western languages. In the last line of a Chinese poem which he had Shiki copy out, he expressed his disgust for languages which were written horizontally instead of, like Japanese, vertically: "Never in your life read that writing which sidles sideways like a crab across the page." (Beichman, Cheng & Tsu Company, 2002, p. 3) By 1892, Shiki having failed an exam, dropped out of college. "You must have heard I received the honor of failing," he wrote. (Beichman, p. 16) Following this, he intensified his studies of haiku — reading every hokku he could find. He blamed his failure at the University on that fact that he could not think of anything but haiku — he was obsessed, or as he wrote, "Bewitched by the goddess of haiku." (ibid) Once out of college, he zealously pursued his haiku ideals and concepts. -

Kanshi, Haiku and Media in Meiji Japan, 1870-1900

The Poetry of Dialogue: Kanshi, Haiku and Media in Meiji Japan, 1870-1900 Robert James Tuck Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Robert Tuck All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Poetry of Dialogue: Kanshi, Haiku and Media in Meiji Japan, 1870-1900 Robert Tuck This dissertation examines the influence of ‘poetic sociality’ during Japan’s Meiji period (1867-1912). ‘Poetic sociality’ denotes a range of practices within poetic composition that depend upon social interaction among individuals, most importantly the tendency to practice poetry as a group activity, pedagogical practices such as mutual critique and the master-disciple relationship, and the exchange among individual poets of textually linked forms of verse. Under the influence of modern European notions of literature, during the late Meiji period both prose fiction and the idea of literature as originating in the subjectivity of the individual assumed hegemonic status. Although often noted as a major characteristic of pre-modern poetry, poetic sociality continued to be enormously influential in the literary and social activities of 19th century Japanese intellectuals despite the rise of prose fiction during late Meiji, and was fundamental to the way in which poetry was written, discussed and circulated. One reason for this was the growth of a mass-circulation print media from early Meiji onward, which provided new venues for the publication of poetry and enabled the expression of poetic sociality across distance and outside of face-to-face gatherings. With poetic exchange increasingly taking place through newspapers and literary journals, poetic sociality acquired a new and openly political aspect. -

J. KEITH VINCENT 745 Commonwealth Avenue #606 Boston, MA 02215 917 214 0302 CURRICULUM VITAE 2018 October [email protected]

J. KEITH VINCENT 745 Commonwealth Avenue #606 Boston, MA 02215 917 214 0302 CURRICULUM VITAE 2018 October [email protected] ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2015 - PRESENT BOSTON UNIVERSITY Chair, Department of World Languages & Literatures (On leave 2018-19) 2013 - PRESENT BOSTON UNIVERSITY Associate Professor of Japanese and Comparative Literature, and Women's, Gender, & Sexuality Studies. 2013 - 2014 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, ANN ARBOR Toyota Visiting Professor 2007 - 2013 BOSTON UNIVERSITY Assistant Professor of Japanese and Comparative Literature Department of Modern Languages & Comparative Literature 2000 - 2007 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies and Comparative Literature Departments of East Asian Studies and Comparative Literature 1998 - 2000 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Lecturer in East Asian Studies and Comparative Literature Departments of East Asian Studies and Comparative Literature EDUCATION 2000 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Ph.D. in East Asian Languages and Cultures Dissertation: “Writing Sexuality: Heteronormativity, Homophobia, and the Homosocial Subject in Modern Japan.” 1993 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY M. Phil. in East Asian Languages and Cultures 1990 - 1991 NAGOYA UNIVERSITY Japanese Ministry of Education’s one-year intensive course on Japanese language and culture for advanced students. Thesis on Muromachi-period linked verse: “Shinkei no renga.” 1990 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS B. A. in East Asian Studies and Comparative Literature Senior thesis: “Literary Naturalism in Japan and France.” 1988 - 1989 PHILIPPS UNIVERSITÄT MARBURG West