Degree Project Level: Bachelor’S a Content Analysis of the Features of Online Discourse on Japanese Twitter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan's Secretive Death Penalty Policy

Japan’s Secretive Death Penalty Policy: Contours, Origins, Justifications, and Meanings♦ David T. Johnson I. ABSTRACT...................................................................................................62 II. “REIKO IN WONDERLAND” .....................................................................63 A. SECRECY AND SILENCE ..............................................................................70 III. ORIGINS .......................................................................................................76 A. MEIJI BIRTH ...............................................................................................76 B. THE OCCUPATION’S “CENSORED DEMOCRACY” ........................................80 C. POSTWAR ACCELERATION..........................................................................87 IV. JUSTIFICATIONS ........................................................................................97 V. MEANINGS.................................................................................................109 A. SECRECY AND LEGITIMACY......................................................................109 B. SECRECY AND SALIENCE ..........................................................................111 C. SECRECY AND DEMOCRACY.....................................................................117 D. SECRECY AND LAW ..................................................................................119 VI. CONCLUSION.............................................................................................123 -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

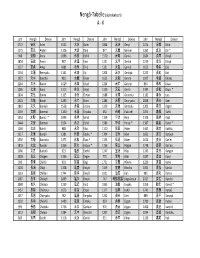

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation Carl Bielefeldt

cover next page > title: Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation author: Bielefeldt, Carl. publisher: University of California Press isbn10 | asin: 0520068351 print isbn13: 9780520068353 ebook isbn13: 9780585111933 language: English subject Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. publication date: 1988 lcc: BQ9449.D657B53 1988eb ddc: 294.3/443 subject: Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i This volume is sponsored by the Center for Japanese Studies University of California, Berkeley < previous page page_i next page > cover next page > title: Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation author: Bielefeldt, Carl. publisher: University of California Press isbn10 | asin: 0520068351 print isbn13: 9780520068353 ebook isbn13: 9780585111933 language: English subject Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. publication date: 1988 lcc: BQ9449.D657B53 1988eb ddc: 294.3/443 subject: Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. cover next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation Carl Bielefeldt University of California Press Berkeley, Los Angeles, London < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv To Yanagida Seizan University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1988 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bielefeldt, Carl. Dogen's manuals of Zen meditation Carl Bielefeldt. p. cm. Bibliography: p. ISBN 0-520-06835-1 (ppk.) 1. Dogen, 1200-1253. -

Library of Clickokinawa.Com 2018

THE U.S. MILITARY OCCUPATION OF OKINAWA: POLITICIZING AND CONTESTING OKINAWAN IDENTITY 1945-1955 VOLUME I by David John Obermiller A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History in the Graduate College of The University of Iowa May 2006 Thesis Supervisor: Professor Stephen Vlastos Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3225658 Copyright 2006 by Obermiller, David John All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3225658 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Copyright by David John Obermiller 2006 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Graduate College The University of Iowa Iowa City, Iowa CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL PH.D. THESIS This is to certify that the Ph.D. thesis of David John Obermiller has been approved by the Examining Committee for the thesis requirement for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History at the May 2006 graduation. -

Encyclopedia of Japanese History

An Encyclopedia of Japanese History compiled by Chris Spackman Copyright Notice Copyright © 2002-2004 Chris Spackman and contributors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” Table of Contents Frontmatter........................................................... ......................................5 Abe Family (Mikawa) – Azukizaka, Battle of (1564)..................................11 Baba Family – Buzen Province............................................... ..................37 Chang Tso-lin – Currency............................................... ..........................45 Daido Masashige – Dutch Learning..........................................................75 Echigo Province – Etō Shinpei................................................................ ..78 Feminism – Fuwa Mitsuharu................................................... ..................83 Gamō Hideyuki – Gyoki................................................. ...........................88 Habu Yoshiharu – Hyūga Province............................................... ............99 Ibaraki Castle – Izu Province..................................................................118 Japan Communist Party – Jurakutei Castle............................................135 -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

Prison Chaplaincy in Japan from the Meiji Period to the Present

Karma and Punishment: Prison Chaplaincy in Japan from the Meiji Period to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40046423 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Karma and Punishment: Prison Chaplaincy in Japan from the Meiji Period to the Present A dissertation presented by Adam J. Lyons to The Committee for the Study of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Japanese Religions Harvard University Cambridge, Massachussetts April 2017 © 2017 Adam J. Lyons All Rights Reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Helen Hardacre Adam J. Lyons Karma and Punishment: Prison Chaplaincy in Japan from the Meiji Period to the Present Abstract #$!%"&!%%'()*)!+,"*,*-./'%"0(!%+,"1$*0-*!,1."2!"#!$%3"!,"4*0*,"5(+6")$'"7'!8!" 0'(!+&"29:;:<9=9>3")+")$'"0('%',)"&*."5+1?%!,@"+,")$'"1$*0-*!,1."*1)!A!)!'%"+5"B$!," C?&&$!%)"%'1)%D"E$(!%)!*,"1$?(1$'%D"B$!,)F"%$(!,'%D"*,&",'G"('-!@!+,%"-!H'"#',(!H.FI" #$'"%+?(1'%"5+(")$!%"%)?&."*('"&(*G,"5(+6"*(1$!A*-"('%'*(1$D"!,)'(A!'G%"G!)$" 1$*0-*!,%D"*,&"%!)'"A!%!)%")+"0(!%+,%"*,&"('-!@!+?%"!,%)!)?)!+,%I"J"*(@?'")$*)")$'" 4*0*,'%'"6+&'-"+5"0(!%+,"1$*0-*!,1."!%"(++)'&"!,")$'"K?('"L*,&"C?&&$!%)"1+,1'0)"+5" -

Download the Japan Style Sheet, 3Rd Edition

JAPAN STYLE SHEET JAPAN STYLE SHEET THIRD EDITION The SWET Guide for Writers, Editors, and Translators SOCIETY OF WRITERS, EDITORS, AND TRANSLATORS www.swet.jp Published by Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators 1-1-1-609 Iwado-kita, Komae-shi, Tokyo 201-0004 Japan For correspondence, updates, and further information about this publication, visit www.japanstylesheet.com Cover calligraphy by Linda Thurston, third edition design by Ikeda Satoe Originally published as Japan Style Sheet in Tokyo, Japan, 1983; revised edition published by Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, CA, 1998 © 1983, 1998, 2018 Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher Printed in Japan Contents Preface to the Third Edition 9 Getting Oriented 11 Transliterating Japanese 15 Romanization Systems 16 Hepburn System 16 Kunrei System 16 Nippon System 16 Common Variants 17 Long Vowels 18 Macrons: Long Marks 18 Arguments in Favor of Macrons 19 Arguments against Macrons 20 Inputting Macrons in Manuscript Files 20 Other Long-Vowel Markers 22 The Circumflex 22 Doubled Letters 22 Oh, Oh 22 Macron Character Findability in Web Documents 23 N or M: Shinbun or Shimbun? 24 The N School 24 The M School 24 Exceptions 25 Place Names 25 Company Names 25 6 C ONTENTS Apostrophes 26 When to Use the Apostrophe 26 When Not to Use the Apostrophe 27 When There Are Two Adjacent Vowels 27 Hyphens 28 In Common Nouns and Compounds 28 In Personal Names 29 In Place Names 30 Vernacular Style