STAC: the Severe Terrain Archaeological Campaign – Investigation of Stack Sites of the Isle of Lewis 2003–2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2004

Fèisean nan Gàidheal The National Association of Gaelic Arts Youth Tuition Festivals Aithisg Bhliadhnail 2004 Annual Report 2004 Fèisean nan Gàidheal Taigh a’ Mhill Port-Rìgh "When heads of state visit this country I’m proud to show them An t-Eilean Sgitheanach our architectural heritage whether it’s a castle, a cottage, or a IV51 9BZ House for an Art Lover. I’m delighted they can hear young musicians from this Academy (RSAMD), and from the Fèis Fòn 01478 613355 movement, play the music of our country." Facs 01478 613399 Post-d [email protected] Jack McConnell MSP, First Minister, St Andrew’s Day Speech, November 2003 www.feisean.org Fèisean nan Gàidheal Aithisg Bhliadhnail 2004 Annual Report 2004 Facal bhon Chathraiche Introduction from the Chairperson 1 FÈISEAN ANN AN ALBA & FÈIS FACTS 2003-04 2 STAFFING 3 FINANCE 4 THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 5 CORE ACTIVITIES & MEMBERSHIP SERVICES 6 DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 2003-04 7 ADVOCACY and COLLABORATION WITH OTHER AGENCIES 8 FÈIS NEWS 9 FINANCIAL STATEMENT Appendix 1 Board Members 2003-04 Appendix 2 Fèis Contacts Fèisean nan Gàidheal is a company limited by guarantee, registration number SC 130071, and gratefully acknowledges the support of its core-funders Scottish Arts Council, The Highland Council and Highlands & Islands Enterprise 2 FACAL BHON CHATHRAICHE Thòisich mi mar Chathraiche Fèisean nan Gàidheal anns an Dùbhlachd an uiridh, a’ leantainn Iain MacDhòmhnaill, a thug seachad mòran bhliadhnaichean gu math soirbheachail anns an dreuchd. Tha e na thoileachadh dhomh Aithisg Bhliadhnail Fèisean nan Gàidheal 2004 a chur fo ur comhair, ann am bliadhna far an robh iomairt nam Fèisean a’ sìor-fhàs agus a’ leudachadh mar nach robh riamh roimhe. -

For Many in the Western Isles the Hebridean

/ - Carpet World 0' /1 -02 3-*0 0-40' ,- 05 3 #$%&' Warehouse ( ) *!" 48 Inaclete Road, Stornoway Tel 01851 705765 www.carpetworldwarehouse.co.uk !" R & G Ury) '$ &$( (Ah) '$ &#&#" ! Jewellery \ "#!$% &'()#'* SS !" !#$$ The local one %% % &##& %# stop solution for all !7ryyShq&"%#% your printing and design needs. GGuideuide ttoo RRallyally HHebridesebrides 22017:017: 01851 700924 [email protected] www.sign-print.co.uk @signprintsty SSectionection FFourour Rigs Road, Stornoway HS1 2RF ' * * + , - + .-- $ ! !"# %& " # $ %&'& $ ())' BANGLA SPICE I6UVS6G SPPADIBTG6U@T :CVRQJ1:J Ury) '$ &$ $$ G 8hyy !" GhCyvr #$!% '$ & '%$ STORNOWAY &! &' ()*+! Balti House ,*-.*/,0121 3 4& 5 5 22 Francis Street Stornoway •# Insurance Services RMk Isle of Lewis HS1 2NB •# Risk Management t: 01851 704949 # ADVICE • Health & Safety YOU CAN www.rmkgroup.co.uk TRUST EVENTS SECTION ONE - Page 2 www.hebevents.com 03/08/17 - 06/09/17 %)% % * + , , -, % ( £16,000 %)%%*+ ,,-, %( %)%%*+ ,,-, %( %*%+*.*,* ' %*%+*.*,* ' presented *(**/ %,, *(**/ %,, *** (,,%( * *** (,,%( * +-+,,%,+ *++,.' +-+,,%,+ *++,.' by Rally #/, 0. 1.2 # The success of last year’s Rally +,#('3 Hebrides was marked by the 435.' !"# handover of a major payment to $%!&' ( Macmillan Cancer Support – Isle of Lewis Committee in mid July. The total raised -

Siadar Wave Energy Project Siadar 2 Scoping Report Voith Hydro Wavegen

Siadar Wave Energy Project Siadar 2 Scoping Report Voith Hydro Wavegen Assignment Number: A30708-S00 Document Number: A-30708-S00-REPT-002 Xodus Group Ltd 8 Garson Place Stromness Orkney KW16 3EE UK T +44 (0)1856 851451 E [email protected] www.xodusgroup.com Environment Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 The Proposed Development 6 1.2 The Developer 8 1.3 Oscillating Water Column Wave Energy Technology 8 1.4 Objectives of the Scoping Report 8 2 POLICY AND LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 10 2.1 Introduction 10 2.2 Energy Policy 10 2.2.1 International Energy Context 10 2.2.2 National Policy 10 2.3 Marine Planning Framework 11 2.3.1 Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 and the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 11 2.3.2 Marine Policy Statement - UK 11 2.3.3 National and Regional Marine Plans 11 2.3.4 Marine Protected Areas 12 2.4 Terrestrial Planning Framework 12 2.5 Environmental Impact Assessment Legislation 12 2.5.1 Electricity Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Scotland) Regulations 2000 13 2.5.2 The Marine Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2007 13 2.5.3 The Environmental Impact Assessment (Scotland) Regulations 1999 13 2.5.4 Habitats Directive and Birds Directive 13 2.5.5 Habitats Regulations Appraisal and Appropriate Assessment 13 2.6 Consent Applications 14 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 15 3.1 Introduction 15 3.2 Rochdale Envelope 15 3.3 Project Aspects 15 3.3.1 Introduction 15 3.3.2 Shore Connection (Causeway and Jetty) 15 3.3.3 Breakwater Technology and Structure 16 3.3.4 Parallel Access Jetty 17 3.3.5 Site Access Road 17 3.3.6 -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

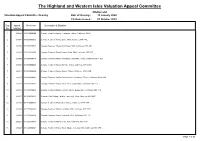

Appeal Citation List External

The Highland and Western Isles Valuation Appeal Committee Citation List Valuation Appeal Committee Hearing Date of Hearing : 15 January 2020 Citations Issued : 01 October 2019 Seq Appeal Reference Description & Situation No Number 1 268564 01/01/900009/0 Sewage Treatment Works, Headworks, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 2 268568 01/05/900001/2 Sewage Treatment Works, Glebe, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4NL 3 268207 01/05/900002/9 Sewage Treatment Works, North Head, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4JH 4 268208 01/05/900003/6 Sewage Treatment Works, Newton Road, Wick, Caithness, KW1 5LT 5 268209 01/09/900001/0 Sewage Treatment Works, Greenland, Castletown, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8SX 6 268210 01/09/900002/7 Sewage Treatment Works, Barrock, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8SY 7 268211 01/09/900003/4 Sewage Treatment Works, Dunnet, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8XD 8 268217 01/09/900004/1 Sewage Treatment Works, Pentland View, Scarfskerry, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8XN 9 268218 01/10/900004/1 Sewage Treatment Works, Thura Place, Bower, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4TS 10 268219 01/10/900005/8 Sewage Treatment Works, Auchorn Square, Bower, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4TN 11 264217 01/11/033541/3 Caravan, Caith Cottage, Hillside, Auckengill, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4XP 12 268935 01/11/900001/7 Sewage Treatment Works, Mey, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8XH 13 268220 01/11/900002/4 Sewage Treatment Works, Canisbay, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4YH 14 268569 01/11/900005/5 Sewage Treatment Works, Auckengill, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4XP 15 268227 01/12/900001/4 Sewage Treatment Works, Reiss, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4RP 16 268228 -

Ken Macdonald & Co Solicitors & Estate Agents Stornoway, Isle Of

Ken MacDonald & Co 2 Lemreway, Lochs, Solicitors & Estate Agents Isle of Lewis,HS2 9RD Stornoway, Isle of Lewis Offers over £115,000 Lounge Description Offered for sale is the tenancy and permanent improvements of the croft extending to approximately 3.04 Ha. The permanent improvements include a well appointed four bedroomed detached dwellinghouse. Presented to the market in good decorative order however would benefit from updating of fixtures and fittings. Benefiting from oil fired central heating and timber framed windows. The property is set back from the main roadway with a garden area to the front with off road parking. Located approximately 30 miles from Stornoway town centre the village of Lemreway is on the east coast of Lewis. Amenities including shop, school and healthcare in the nearby villages of Kershader and Gravir approximately 5 Bathroom miles away. Sale of the croft is subject to Crofting Commission approval. Directions Travelling out of Stornoway town centre passing the Co-op superstore take the first turning to your left at the roundabout. Follow the roadway for approximately 16 miles travelling through the villages of Leurbost, Laxay and Balallan. At the end of Balallan turn to your left hand side and follow the roadway through the district of South Lochs for approximately 13 miles passing through Habost, Kershader, Garyvard and Gravir until you reach the village Lemreway. Continue straight ahead and travel approximately 0.8 miles. Number 2 Lemreway is the second last house on your right hand side. Bedroom 1 EPC BAND E Bedroom 2 Bedroom 3 Bedroom 4 Rear Aspect Croft and outbuilding View Plan description Porch 2.07m (6'9") x 1.59m (5'3") Vinyl flooring. -

Standard Committee Report

ENVIRONMENT AND PROTECTIVE SERVICES COMMITTEE: 9 FEBRUARY 2010 APPLICATION FOR PLANNING PERMISSION FOR A TIME AND TIDE BELL AT BOSTA, GREAT BERNERA, ISLE OF LEWIS (REF 09/00608/PPD) Report by Director of Development PURPOSE OF REPORT Since this proposal received over three letters of representation from separate parties which contain matters which are relevant material planning considerations, the application should not be dealt with under delegated powers and is presented to the Comhairle for a decision. COMPETENCE 1.1 There are no legal, financial or other constraints to the recommendation being implemented. SUMMARY 2.1 This is an application by Bernera Community Council for full planning permission for the erection of a Time and Tide bell installation, at Bosta Beach on Great Bernera. Objections have been raised by a number of people, relating to noise pollution, changing the character of the area, lack of public consultation and disruption to birds, as well as a number of other issues that are not considered to be material planning considerations. 2.2 It is considered that the proposal is not viewed as contrary to the Development Plan. The issues raised have been considered but not deemed significant enough to warrant refusal or are proposed to be dealt with through planning conditions. The development is considered in accordance with the Development Plan and is therefore recommended for approval. RECOMMENDATION 3.1 It is recommended that the application be APPROVED subject to the conditions shown in Appendix 1. Contact Officer Helen Maclennan Tel: 01851 709284 e-mail: [email protected] Appendix 1 Scheduleproposed of conditions 2 Location plan Background Papers: None 15/02/2010 REPORT DETAILS DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSAL 4.1 This is an application for the erection of a Time and Tide bell installation, at Bosta Beach on Great Bernera. -

Cromore & Calbost

In brief Category: Easy / Moderate 1 = Other Walking & Cycle Routes Map Reference: OS Landranger 7 Map 14 (Tarbert & Loch Seaforth); OS Explorer Map 457 (South East 8 9 Lewis) 1 2 Calbost & Cromore Start and End Grid Reference: Cromore NB 381 177 & Calbost Cycling Distance: 24 km / 15 miles 10 9 3 Time: 2 hours 4 11 5 12 13 Route Route Cycling Cycling 14 Our walking and cycling routes are part of a series of self-guided trails through 6 the Outer Hebrides. For more information 15 16 scan here. Cycling is a great way to discover our www.visitouterhebrides.co.uk islands and enjoy the outdoors. With www.visitouterhebrides.co.uk/apps routes to suit all ages and abilities, South Lewis and minimal traffic on many island roads, cycling can be as leisurely or as challenging as you choose. “This excellent cycling route If you don’t own a bike, a number of follows quiet single track establishments offer bike hire – check out roads that thread their way www.visitouterhebrides.co.uk for more details through the hills and lochs of the district. You will meet very little traffic so there will Courteous and Safe Cycling be plenty of time to enjoy Most of the vehicles that pass you on your bike the stunning views. Keep an are going about their daily business, so we would eye out for golden and white In brief ask you to respect these few guidelines to keep In brief Category: Moderate Category: Difficult Map Reference: OS Landranger Map tailed (or sea) eagles, both of 31 (Barra & South Uist): OS Explorer everyone safe and moving with ease: Map Reference: -

Prògram Iomall A' Mhòid 2016

MÒD NAN EILEAN SIAR 2016 | PRÒGRAM IOMALL A' MHÒID | FRINGE PROGRAMME PRÒGRAM IOMALL A' MHÒID 2016 FRINGE PROGRAMME 2016 MÒD NAN EILEAN SIAR 2016 | PRÒGRAM IOMALL A' MHÒID | FRINGE PROGRAMME MÒD NAN EILEAN SIAR 2016 | PRÒGRAM IOMALL A' MHÒID | FRINGE PROGRAMME Dihaoine 14mh Dàmhair Friday 14th October CAISMEACHD LÒCHRANACH TALLA BHAILE STEÒRNABHAIGH | BHO 6.30F, A’ FÀGAIL AIG 6.45F Tha na h-Eileanan Siar a’ cur fàilte air a’ Mhòd Nàiseanta Rìoghail, le caismeachd mhòr nan Lochran, le Còmhlan Pìoba Leòdhais air an ceann. Bithear a’ caismeachd tro bhaile Steòrnabhaigh gu ruige Ionad Spòrs Leòdhais, airson cuirm fosglaidh a’ Mhòid. TORCHLIGHT PROCESSION STORNOWAY TOWN HALL | FROM 6.30PM, DEPARTING AT 6.45PM The Western Isles welcomes the Royal National Mòd with a torchlight procession led by the Lewis Pipe Band through Stornoway to Lewis Sports Centre for the Opening Ceremony. FOSGLADH OIFIGEIL IONAD SPÒRS LEÒDHAIS | 8F | BALL: AN ASGAIDH | GUN BHALLRACHD: £5 Tachartas fosglaidh a’ Mhòid Nàiseanta Rìoghail, le ceòl bho Dàimh agus ceòl-triùir Mischa Nic a’ Phearsain, air a thaisbeanadh le Kirsteen NicDhòmhnaill. OFFICIAL OPENING LEWIS SPORTS CENTRE | 8PM | MEMBER: FREE | NON-MEMBER: £5 The opening ceremony of the Royal National Mòd, featuring music from Dàimh and the Mischa Macpherson Trio, presented by Kirsteen MacDonald. CÈILIDH A’ MHÒID AN LANNTAIR | 10.30F | £10 Tiugainn a’dhannsa! Cuide ris a’ chòmhlan Ghàidhlig traidiseanta aithnichte ‘Dàimh’. MÒD CEILIDH AN LANNTAIR | 10.30PM | £10 Dance the night away with Gaelic super-group Dàimh. www.ancomunn.co.uk MÒD NAN EILEAN SIAR 2016 | PRÒGRAM IOMALL A' MHÒID | FRINGE PROGRAMME Disathairne 15mh Dàmhair Saturday 15th October CAMANACHD BALL-COISE A’ MHÒID A’ MHÒID PÀIRC SHIABOIST | 2F PÀIRC GHARRABOIST, AN RUBHA | 3F AN ASGAIDH AN ASGAIDH Leòdhas agus An t-Eilean Sgitheanach Sgioba Leòdhais ‘s na Hearadh a’ dol an a’ dol an aghaidh a chèile airson Cupa aghaidh Glasgow Island AFC airson a’ Mhòid. -

Site Selection Document: Summary of the Scientific Case for Site Selection

West Coast of the Outer Hebrides Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) No. UK9020319 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Scotland Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed in preparation for possible formal Scotland consultation. 30/06/15 Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Updated with minor amendments to address Marine comments from Marine Scotland Science in Scotland preparation for the SPA stakeholder workshop. 23/02/16 Emma Philip Version 4 Revised format, using West Coast of Outer MPA Hebrides as a template, to address comments Project received at the SPA stakeholder workshop. Steering Emma Philip Group 07/04/16 Version 5 Text updated to reflect proposed level of detail for Marine final versions. Scotland Emma Philip 18/04/16 Version 6 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Glen Tyler & Emma Philip 19/06/16 Version 7 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 20/6/16 Version 8 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 9 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 2. Site summary ..................................................................................................... 2 3. Bird survey information .................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines ................................. 7 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................ 13 6. Information on qualifying species ................................................................. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Folklore of The

1 Cailleach – old woman Altough the Cailleach lives in various mountain homes every year she comes to the Coire Bhreacain (Cauldren of the Plaid) to wash her massive yellow plaid in the swirling waters in order to summon the cold winds as Scotia’s Winter goddess. During archeological excavations in 1880 a figure of an ancient goddess was discovered in the peat bogs of Scotland, a figure who 2,500 years ago stood near the shore of Loch Leven as a symbol of an ancient religion or deity that has now been lost to time. Today she is known as the Ballachulish Woman & is a figure who stands at almost five feet tall & carved from a single piece of alder wood, her eyes are two quartz pebbles which even today, have a remarkable ability to draw the attention to the face of this mysterious relic. Although the identity of the Ballachulish Woman still remains a mystery many have speculated as to who this figure represented, there are some who believe that she is a depiction of a deity known as the Cailleach Bheithir, an ancient goddess of winds & 2 storms, also known as the Winter Hag, who had associations with a nearby mountain called Beinn a’Bheithir. (Hill of the thunderbolt) Another theory is that she could represent a goddess of the straits, this is due to the figures location near the straits where Loch Levan meets the sea, & was a deity that prehistoric travellers would make offerings too in an attempt to secure their safety while travelling dangerous waters.