A History of the Papacy from the Great Schism to the Sack of Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QUESTION 39 Schism We Next Have to Consider the Vices That Are Opposed to Peace and That Involve Deeds: Schism (Schisma) (Quest

QUESTION 39 Schism We next have to consider the vices that are opposed to peace and that involve deeds: schism (schisma) (question 39); strife (rixa) (question 41); sedition (seditio) (question 42); and war (bellum) (question 40). On the first topic there are four questions: (1) Is schism a special sin? (2) Is schism a more serious sin than unbelief? (3) Do schismatics have any power? (4) Are schismatics appropriately punished with excommunication? Article 1 Is schism a special sin? It seems that schism is not a special sin: Objection 1: As Pope Pelagius says, “Schism (schisma) sounds like scissor (scissura).” But every sin effects some sort of cutting off—this according to Isaiah 59:2 (“Your sins have cut you off from your God”). Therefore, schism is not a special sin. Objection 2: Schismatics seem to be individuals who do not obey the Church. But a man becomes disobedient to the precepts of the Church through every sin, since sin, according to Ambrose, “is disobedience with respect to the celestial commandments.” Therefore, every sin is an instance of schism. Objection 3: Heresy likewise cuts a man off from the unity of the Faith. Therefore, if the name ‘schism’ implies being cut off, then schism does not seem to differ as a special sin from the sin of unbelief. But contrary to this: In Contra Faustum Augustine distinguishes schism from heresy as follows: “Schism is believing the same things as the others and worshiping with the same rites, but being content merely to split the congregation, whereas heresy is believing things that are diverse from what the Catholic Church believes.” Therefore, schism is not a general sin. -

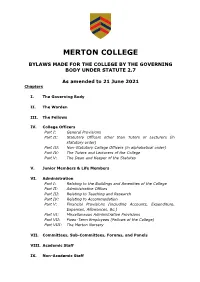

Merton College Bylaws As at 2021-06-21

MERTON COLLEGE BYLAWS MADE FOR THE COLLEGE BY THE GOVERNING BODY UNDER STATUTE 2.7 As amended to 21 June 2021 Chapters I. The Governing Body II. The Warden III. The Fellows IV. College Officers Part I: General Provisions Part II: Statutory Officers other than Tutors or Lecturers (in statutory order) Part III: Non-Statutory College Officers (in alphabetical order) Part IV: The Tutors and Lecturers of the College Part V: The Dean and Keeper of the Statutes V. Junior Members & Life Members VI. Administration Part I: Relating to the Buildings and Amenities of the College Part II: Administrative Offices Part III: Relating to Teaching and Research Part IV: Relating to Accommodation Part V: Financial Provisions (including Accounts, Expenditure, Expenses, Allowances, &c.) Part VI: Miscellaneous Administrative Provisions Part VII: Fixed-Term Employees (Fellows of the College) Part VIII: The Merton Nursery VII. Committees, Sub-Committees, Forums, and Panels VIII. Academic Staff IX. Non-Academic Staff X. The Common Table, The Common Room, College Dinners and Entertainment Part I: The Common Room Part II: The Common Table Part III: College Dinners and Entertainment XI. Discipline and Fitness to Study of Junior Members XI A: Academic Discipline XI B: Discipline for Serious Misconduct XI C: Failure in the First Public Examination XI D: Suspension and Fitness to Study Appendices A. Bylaw VI.1(b): Commemoration of Benefactors B. Bylaw VI.39: Policies adopted by the Governing Body 1. EJRA Policy 2012 2. Information Security a. Information Security Policy 2018 b. Data Protection Policy 2018 c. Data Protection Breach Regulations 2018 d. Mobile Device Security Regulations 2018 e. -

Slezský Sborník Acta Silesiaca

SLEZSKÝ SBORNÍK ACTA SILESIACA ROČNÍK CVIII / 2010 ČÍSLO 1–2 STUDIE / ARTICLES Robert ANTONÍN: Jan Lucemburský a slezská knížata v letech 1327–1329 5–21 John the Blind and Princes of Silesia in the Years 1327–1329 The study based on the analysis of narrative sources and sources of diplomatic character shows that in Polish politics of John the Blind in the 1320s is discernible a long-term tendency to subdue the Silesian territories. Firstly, they formed a buffer zone between the traditional Bohemian crown lands and parts of Poland that were controlled by Władysław I the Elbow-high (Pol. Łokietek), secondly, they represented an important centre of Central-European economy. Key Words: Middle Ages; history of Silesia; John the Blind; John of Bohemia; John of Luxembourg; 14th century; Princes of Silesia Mario MÜLLER: Der Glogauer Erbfolgestreit (1476–1482) zwischen den 22–59 Markgrafen von Brandenburg, Herzog Johann II. von Sagan und Matthias Corvinus, König von Ungarn und Böhmen The Głogów war of succession (1476–1482) between the margrave of Brandenburg, Duke John (Johann) II of Żagań and King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary and Bohemia Válka o hlohovské dědictví (1476–1482) mezi braniborskými markrabaty, kníņetem Janem II. Zaháňským a uherským a českým králem Matyáńem Korvínem The Głogów (Germ. Glogau) war of succession describes the war between the margrave of Brandenburg and Duke John II of Żagań (Germ. Sagan) over the Duchy of Głogów. It broke out after the death of Duke Henry XI on February 22nd, 1476, and found its end in the Treaty of Kamenz in September 1482. This war of succession obtained nationwide significance because of the contemporary confu- sion over the Bohemian throne, fought between King Matthias and Vladislav II, son of the Polish King Casimir IV Jagiełło. -

Anatomy of Melancholy by Democritus Junior

THE ANATOMY OF MELANCHOLY WHAT IT IS WITH ALL THE KINDS, CAUSES, SYMPTOMS, PROGNOSTICS, AND SEVERAL CURES OF IT IN THREE PARTITIONS; WITH THEIR SEVERAL SECTIONS, MEMBERS, AND SUBSECTIONS, PHILOSOPHICALLY, MEDICINALLY, HISTORICALLY OPENED AND CUT UP BY DEMOCRITUS JUNIOR [ROBERT BURTON] WITH A SATIRICAL PREFACE, CONDUCING TO THE FOLLOWING DISCOURSE PART 2 – The Cure of Melancholy Published by the Ex-classics Project, 2009 http://www.exclassics.com Public Domain CONTENTS THE SYNOPSIS OF THE SECOND PARTITION............................................................... 4 THE SECOND PARTITION. THE CURE OF MELANCHOLY. .............................................. 13 THE FIRST SECTION, MEMBER, SUBSECTION. Unlawful Cures rejected.......................... 13 MEMB. II. Lawful Cures, first from God. .................................................................................... 16 MEMB. III. Whether it be lawful to seek to Saints for Aid in this Disease. ................................ 18 MEMB. IV. SUBSECT. I.--Physician, Patient, Physic. ............................................................... 21 SUBSECT. II.--Concerning the Patient........................................................................................ 23 SUBSECT. III.--Concerning Physic............................................................................................. 26 SECT. II. MEMB. I....................................................................................................................... 27 SUBSECT. I.--Diet rectified in substance................................................................................... -

Pdfeast-West-Schism.Pdf 97 KB

Outline the events that lead to an overall schism between the church of the East and the West. Was such a schism inevitable given the social, political and ecclesiastical circumstances? Name: Iain A. Emberson Module: Introducing Church History Essay Number: 1 Tutor: Richard Arding Date: 11 November 2009 1 Outline 1. Introduction 2. Greek and Latin Cultural Differences 3. Rome and Constantinople 4. The Filioque 5. The Iconoclastic Controversy 6. The Photian Schism 7. Excommunication and Final Schism 8. Aftermath and Reflection 9. Conclusion 10. Bibliography 2 1. Introduction The East-West Schism (also known as the Great Schism) resulted in the division of Christianity into Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) branches. The mutual excommunications in 1054 marked the climax to a long period of tension between the two streams of Christianity and resulted from, amongst other things, cultural, linguistic, political and theological differences that had built up over time. Here we examine a number of these differences and their ultimate culmination in dividing East from West. 2. Greek and Latin Cultural Differences In his work 'Turning Points', Noll argues that “As early as the first century, it was possible to perceive pointed differences between the representatives of what would one day be called East and West.” 1 The Eastern Orthodox theologian Timothy Ware expands on this: From the start, Greeks and Latins had each approached the Christian mystery in their own way. At the risk of some oversimplification, it can be said that the Latin approach was more practical, the Greek more speculative; Latin thought was influenced by judicial ideas...while the Greeks understood theology in the context of worship and in the light of the Holy Liturgy.. -

The Short Outline of the History of the Czech Lands in The

Jana Hrabcova 6th century – the Slavic tribes came the Slavic state in the 9th century situated mostly in Moravia cultural development resulted from the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius – 863 translation of the Bible into the slavic language, preaching in slavic language → the Christianity widespread faster They invented the glagolitic alphabet (glagolitsa) 885 – Methodius died → their disciples were expeled from G.M. – went to Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia etc., invented cyrilic script http://www.filmcyrilametodej.cz/en/about-film/ The movie (document) about Cyril and Methodius the centre of the duchy in Bohemia Prague the capital city 10th century – duke Wenceslaus → assassinated by his brother → saint Wenceslaus – the saint patron of the Czech lands the Kingdom of Bohemia since the end of 12th century Ottokar II (1253–1278, Přemysl Otakar II) – The Iron and Golden King very rich and powerful – his kingdom from the Krkonoše mountains to the Adriatic sea 1278 – killed at the battle of Dürnkrut (with Habsburgs) Wenceslaus II of Bohemia (1278–1305) – king of Bohemia, King of Poland Wenceslaus III (1305–1306) – assassinated without heirs The kingdom of Ottokar II The Kingdom of Wenceslaus II Around 1270 around 1301 John of Bohemia (1310–1346, John the Blind) married Wenceslaus’s sister Elizabeth (Eliška) Charles IV the king of Bohemia (1346–1378) and Holy Roman Emperor (1355–1378) . The Holy Roman Empire (962–1806) – an empire existing in Europe since 962 till 1806, ruled by Roman Emperor (present –day territories of Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Switzerland and Liechenstein, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia, parts of eastern France, nothern Italy and western Poland) the most important and the best known Bohemian king 1356 - The Golden Bull – the basic law of the Holy Roman Empire Prague became his capital, and he rebuilt the city on the model of Paris, establishing the New Town of Prague (Nové Město), Charles Bridge, and Charles Square, Karlštejn Castle etc. -

Tanulmányt Alap

'W,- Ö -χ "V& > f\ • % :\i.\<; YA iíoiísza(ÍI Κ I I; Л Ь A I TANULMÁNYT ALAP \ í \i 1 í ^M'íi^i íí'k'Vi ^rjl'x" • ч r • M /w i i ι ΛΙ Γ,ΓνΜ χ, i l i, Λ EIN r \ Ι UN : \'I '/ Jο^ ιv i' ,·л \ τi JA w. »g ? .· νν тi м\ Ул V wO/jу Vί 71\ ϊ ilί i \ i Τ ? VEZÉ KORMÁNYOK. \ r~ \ ι X / \ / \ Λ VALLAS KS ΚΟΖΟΚΤΛΤΑΚΠίΥΙ Μ. Κ11. MIXI ST КI ί MK< Míi/ASÁI'.OL. Ρ UDAPESTEN. NYOMATOTT Λ ΜΛΟΥΛΙί ΚίΙί. J.OYΈΤΚΜΙ KÖN ΥΥΝ ΥΟ.ΜΟΛΒΛΧ. № η V' Y. 1 S A f) ' V Ov ' 4 9 / ; 4: с f А ζ' г χ' {1 ί f ί A MAGYARORSZÁGI KIR TANULMÁNYI ALAP JOGI r _ r r, TERMESZETENEK MEGVIZSGÁL AS ARA SZOLGÁLÓ YE ZÉRÓK MÁN Y OK. A VALLÁS ÉS KÖZOKTATÁSÜGYI M. KIR. MINISTER MEGBÍZÁSÁBÓL. ÁLL. POLGÁRI I3K. TANI10KÉPZÖ INT. KÖNYVTÁRA jf Érteett: 19 dÂÂ^s1 Leltári szÁm Csoportszám·^ | BUDAPESTEN. NYOMATOTT A MAGYAR KIR. EGYETEMI KÖNYVNYOMDÁBAN. A magyarországi kir. tanulmányi alapjogi természetének megvizsgálására szolgáló vezérokmányok jegyzéke. Lap. Lap. I. XIV. Kelemen pápának a jezsuita-rend meg- IX. D. e. Mária Terézia római császárné és ma- szüntetése iránt 1773.* évi julius 21-én kiadott gyar királynő alapitó-levele 1780. évi marczius brevéje 1 25-éről a jezsuita-rend vagyonából a magyar és horvát tanulmányi alap alakítása, és a magyar II. D. e. Mária Terézia római császárné és magyar tanulmányi és az egyetemi alap némely javainak királynőnek a m. k. helytartótanácshoz 1773. kicserélése iránt 35 évi september 20-án intézett leirata, melylyel a megszüntetett jezsuita-rend vagyonának a X. -

Ungleiche Entwicklung in Zentraleuropa. Galizien

Ungleiche Entwicklung in Zentraleuropa SOZIAL- UND WIRTSCHAFTSHISTORISCHE STUDIEN Institut für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte Universität Wien Gegründet von Alfred Hoffmann und Michael Mitterauer Herausgegeben von Carsten Burhop, Markus Cerman, Franz X. Eder, Josef Ehmer, Peter Eigner, Thomas Ertl, Erich Landsteiner und Andrea Schnöller Wissenschaftlicher Beirat: Birgit Bolognese-Leuchtenmüller Ernst Bruckmüller Alois Ecker Herbert Knittler Andrea Komlosy Michael Mitterauer Andrea Pühringer Reinhard Sieder Hannes Stekl Dieter Stiefel Band 37 Klemens Kaps UNGLEICHE ENTWICKLUNG IN ZENTR ALEUROPA Galizien zwischen überregionaler Verflechtung und imperialer Politik (1772–1914) 2015 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : PUB 214-V16 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2015 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H., Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Lektorat : Dr. Andrea Schnöller, Wien Satz : Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung : Prime Rate, Budapest Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in the EU ISBN 978-3-205-79638-1 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Danksagung ................................ -

The Ginger Fox's Two Crowns Central Administration and Government in Sigismund of Luxembourg's Realms

Doctoral Dissertation THE GINGER FOX’S TWO CROWNS CENTRAL ADMINISTRATION AND GOVERNMENT IN SIGISMUND OF LUXEMBOURG’S REALMS 1410–1419 By Márta Kondor Supervisor: Katalin Szende Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, Central European University, Budapest in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, CEU eTD Collection Budapest 2017 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION 6 I.1. Sigismund and His First Crowns in a Historical Perspective 6 I.1.1. Historiography and Present State of Research 6 I.1.2. Research Questions and Methodology 13 I.2. The Luxembourg Lion and its Share in Late-Medieval Europe (A Historical Introduction) 16 I.2.1. The Luxembourg Dynasty and East-Central-Europe 16 I.2.2. Sigismund’s Election as King of the Romans in 1410/1411 21 II. THE PERSONAL UNION IN CHARTERS 28 II.1. One King – One Land: Chancery Practice in the Kingdom of Hungary 28 II.2. Wearing Two Crowns: the First Years (1411–1414) 33 II.2.1. New Phenomena in the Hungarian Chancery Practice after 1411 33 II.2.1.1. Rex Romanorum: New Title, New Seal 33 II.2.1.2. Imperial Issues – Non-Imperial Chanceries 42 II.2.2. Beginnings of Sigismund’s Imperial Chancery 46 III. THE ADMINISTRATION: MOBILE AND RESIDENT 59 III.1. The Actors 62 III.1.1. At the Travelling King’s Court 62 III.1.1.1. High Dignitaries at the Travelling Court 63 III.1.1.1.1. Hungarian Notables 63 III.1.1.1.2. Imperial Court Dignitaries and the Imperial Elite 68 III.1.1.2. -

Form: Rcia Supplemental Marriage Information

DOCUMENT 615C FORM: RCIA SUPPLEMENTAL MARRIAGE INFORMATION PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY -- CORRECT SPELLING OF NAMES IS MOST IMPORTANT Current Last Name: Maiden Name (if applicable): Given Name(s): Sex □ M □ F CURRENT MARITAL STATUS: ✓ all applicable items □ Engaged to be Married (Complete Section I) □ Currently Married by Religious Service; Civil; etc (Complete Section II) □ Previously Married (Complete Section III) □ Current Fiancé(e) or Spouse was previously married (Complete Section III) SECTION I | ENGAGED TO BE MARRIED 1) Will this be your first marriage? □ Yes □ No; If no, please complete SECTION III. 2) Name of Fiancé(e): 3) Is this your Fiancé(e)’s first marriage? □ Yes □ No; If no, please complete SECTION III. 4) Is your Fiancé(e) baptized? □ Yes □ No; If Yes, what Christian denomination? 5) If no, what faith tradition (if any) does he/she identify with? 6) In what kind of celebration or ritual will your upcoming marriage be witnessed? □ Catholic (Latin or Eastern Rite); □ Orthodox; □ Christian (Other); □ Religion (Other); | □ Civil/Non-Faith. Notations (if any): 7) Who will preside at your wedding? □ Priest/Deacon; □ Non-Catholic Minister; □ Justice of the Peace; □ Other: 8) If you are wanting your marriage recognized by the Catholic Church, have you discussed either of the following with your Parish Priest?: □ a Marriage Dispensation; □ a Convalidation (“Blessing”) 615C- Supplemental Marriage Information 2018/03 Page 1 of 4 DOCUMENT 615C SECTION II | CURRENT MARRIAGE (RELIGIOUS SERVICE: CIVIL; ETC.): 1) Is this your first marriage? □ Yes □ No; If no, please complete Section III. 2) Name of Spouse: 3) Is this your Spouse’s first marriage? □ Yes □ No; If no, please complete Section III. -

The College and Canons of St Stephen's, Westminster, 1348

The College and Canons of St Stephen’s, Westminster, 1348 - 1548 Volume I of II Elizabeth Biggs PhD University of York History October 2016 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the college founded by Edward III in his principal palace of Westminster in 1348 and dissolved by Edward VI in 1548 in order to examine issues of royal patronage, the relationships of the Church to the Crown, and institutional networks across the later Middle Ages. As no internal archive survives from St Stephen’s College, this thesis depends on comparison with and reconstruction from royal records and the archives of other institutions, including those of its sister college, St George’s, Windsor. In so doing, it has two main aims: to place St Stephen’s College back into its place at the heart of Westminster’s political, religious and administrative life; and to develop a method for institutional history that is concerned more with connections than solely with the internal workings of a single institution. As there has been no full scholarly study of St Stephen’s College, this thesis provides a complete institutional history of the college from foundation to dissolution before turning to thematic consideration of its place in royal administration, music and worship, and the manor of Westminster. The circumstances and processes surrounding its foundation are compared with other such colleges to understand the multiple agencies that formed St Stephen’s, including that of the canons themselves. Kings and their relatives used St Stephen’s for their private worship and as a site of visible royal piety. -

The Birth of an Empire of Two Churches : Church Property

The Birth of an Empire of Two Churches: Church Property, Theologians, and the League of Schmalkalden CHRISTOPHER OCKER ID THE CREATION OF PROTESTANT CHURCHES IN GERMANY during Luther’s generation follow someone’s intentions? Heiko Oberman, appealing to a medieval DLuther, portrays the reformer as herald of a dawning apocalypse, a monk at war with the devil, who expected God to judge the world and rescue Christians with no help from human institutions, abilities, and processes.1 This Luther could not have intended the creation of a new church. Dorothea Wendebourg and Hans-Jürgen Goertz stress the diversity of early evangelical movements. Goertz argues that anticlericalism helped the early Reformation’s gamut of spiritual, political, economic, and social trends to coalesce into moderate and radical groups, whereas Wendebourg suggests that the movements were only united in the judgment of the Counter Reformation.2 Many scholars concede this diversity. “There were very many different Reformations,” Diarmaid McCulloch has recently observed, aimed “at recreating authentic Catholic Christianity.”3 But some intention to form a new church existed, even if the intention was indirect. Scholars have identified the princely reaction to the revolting peasants of 1524–1525 as the first impetus toward political and institutional Protestantism.4 There was a 1Heiko A. Oberman, Die Wirkung der Reformation: Probleme und Perspektiven, Institut für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Vorträge 80 (Wiesbaden, 1987), 46; idem, Luther: Man between God and the Devil (New York, 1992), passim; idem, “Martin Luther zwischen Mittelalter und Neuzeit,” in Die Reformation: Von Wittenberg nach Genf (Göttingen, 1987), 189–207; Scott Hendrix, “‘More Than a Prophet’: Martin Luther in the Work of Heiko Oberman,” in The Work of Heiko A.