Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pioneer's Big Lie

COMMENTARIES PIONEER'S BIG LIE Paul A. Lombardo* In this they proceeded on the sound principle that the magnitude of a lie always contains a certain factor of credibility, since the great masses of the people in the very bottom of their hearts tend to be corrupted rather than consciously and purposely evil, and that, therefore, in view of the primitive simplicity of their minds, they more easily fall a victim to a big lie than to a little one, since they themselves lie in little things, but would be ashamed of lies that were too big. Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf' In the spring of 2002, I published an article entitled "The American Breed" Nazi Eugenics and the Origins of the Pioneer Fund as part of a symposium edition of the Albany Law Review.2 My objective was to present "a detailed analysis of the.., origins of the Pioneer Fund"3 and to show the connections between Nazi eugenics and one branch of the American eugenics movement that I described as purveying "a malevolent brand of biological determinism."4 I collected published evidence on the Pioneer Fund's history and supplemented it with material from several archival collections-focusing particularly on letters and other documents that explained the relationship between Pioneer's first President, 'Paul A. Lombardo, Ph.D., J.D., Director, Program in Law and Medicine, University of Virginia Center for Bioethics. I ADOLF HITLER, MEIN KAMPF 231 (Ralph Manheim trans., Houghton Mifflin Co. 1971) (1925). 2 Paul A. Lombardo, "The American Breed" Nazi Eugenics and the Origins of the Pioneer Fund, 65 ALB. -

The Sociopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America

Voces Novae Volume 11 Article 3 2019 Engineering Mankind: The oS ciopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America Megan Lee [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Part of the American Politics Commons, Bioethics and Medical Ethics Commons, Genetics and Genomics Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Megan (2019) "Engineering Mankind: The ocS iopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America," Voces Novae: Vol. 11, Article 3. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lee: Engineering Mankind: The Sociopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America Engineering Mankind: The Sociopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America Megan Lee “It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind…Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”1 This statement was made by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. while presenting the court’s majority opinion on the sterilization of a seventeen-year old girl in 1927. The concept of forced sterilization emerged during the American Eugenics Movement of the early 20th century. In 1909, California became one of the first states to introduce eugenic laws which legalized the forced sterilization of those deemed “feeble-minded.” The victims were mentally ill patients in psychiatric state hospitals, individuals who suffered from epilepsy and autism, and prisoners with criminal convictions, all of whom were forcibly castrated. -

Anthropology and the Racial Politics of Culture

ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE RACIAL POLITICS OF CULTURE Lee D. Baker Anthropology and the Racial Politics of Culture Duke University Press Durham and London ( 2010 ) © 2010 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Warnock with Magma Compact display by Achorn International, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Dedicated to WILLIAM A. LITTLE AND SABRINA L. THOMAS Contents Preface: Questions ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 (1) Research, Reform, and Racial Uplift 33 (2) Fabricating the Authentic and the Politics of the Real 66 (3) Race, Relevance, and Daniel G. Brinton’s Ill-Fated Bid for Prominence 117 (4) The Cult of Franz Boas and His “Conspiracy” to Destroy the White Race 156 Notes 221 Works Cited 235 Index 265 Preface Questions “Are you a hegro? I a hegro too. Are you a hegro?” My mother loves to recount the story of how, as a three year old, I used this innocent, mis pronounced question to interrogate the garbagemen as I furiously raced my Big Wheel up and down the driveway of our rather large house on Park Avenue, a beautiful tree-lined street in an all-white neighborhood in Yakima, Washington. It was 1969. The Vietnam War was raging in South- east Asia, and the brutal murders of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Bobby and John F. Kennedy hung like a pall over a nation coming to grips with new formulations, relations, and understand- ings of race, culture, and power. -

Totalitarian Dynamics, Colonial History, and Modernity: the US South After the Civil War

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

"Black Colorism and White Racism: Discourse on the Politics of White Supremacy, Black Equality, and Racial Identity, 1915-1930"

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2020 "Black Colorism and White Racism: Discourse on the Politics of White Supremacy, Black Equality, and Racial Identity, 1915-1930" Hannah Paige McDonald University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation McDonald, Hannah P. "Black Colorism and White Racism: Discourse on the Politics of White Supremacy, Black Equality, and Racial Identity, 1915-1930." Master's thesis, University of Montana, 2020. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLACK COLORISM AND WHITE RACISM: DISCOURSE ON THE POLITICS OF WHITE SUPREMACY, BLACK EQUALITY, AND RACIAL IDENTITY, 1915-1930 By HANNAH PAIGE MCDONALD Bachelor of Arts in History, The University of Montana, Missoula, MT, 2017 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2020 Approved -

Problem and Promise: Scientific Experts and the Mixed-Blood in the Modern U.S., 1870-1970

PROBLEM AND PROMISE: SCIENTIFIC EXPERTS AND THE MIXED-BLOOD IN THE MODERN U.S., 1870-1970 By Michell Chresfield Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2016 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Sarah Igo, Ph.D. Daniel Sharfstein, J.D. Arleen Tuchman, Ph.D. Daniel Usner, Ph.D. Copyright © 2016 by Michell Chresfield All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the result of many years of hard work and sacrifice, only some of which was my own. First and foremost I’d like to thank my parents, including my “bonus mom,” for encouraging my love of learning and for providing me with every opportunity to pursue my education. Although school has taken me far away from you, I am forever grateful for your patience, understanding, and love. My most heartfelt thanks also go to my advisor, Sarah Igo. I could not have asked for a more patient, encouraging, and thoughtful advisor. Her incisive comments, generous feedback, and gentle spirit have served as my guideposts through one of the most challenging endeavors of my life. I am so fortunate to have had the opportunity to grow as a scholar under her tutelage. I’d also like to thank my dissertation committee members: Arleen Tuchman, Daniel Sharfstein, and Daniel Usner for their thoughtful comments and support throughout the writing process. I’d especially like to thank Arleen Tuchman for her many pep talks, interventions, and earnest feedback; they made all the difference. I’d be remiss if I didn’t also thank my mentors from Notre Dame who first pushed me towards a life of the mind. -

Tidewater Native Peoples and Indianness in Jim Crow Virginia

Constructing and Contesting Color Lines: Tidewater Native Peoples and Indianness in Jim Crow Virginia By Laura Janet Feller B.A., Westhampton College of the University of Richmond, 1974 M.A., The George Washington University, 1983 A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2009 Dissertation directed by James Oliver Horton Benjamin Banneker Professor of American Studies and History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Laura Janet Feller has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of December 4, 2008. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Constructing and Contesting Color Lines: Tidewater Native Peoples and Indianness in Jim Crow Virginia Laura Janet Feller Dissertation Research Committee: James Oliver Horton, Benjamin Banneker Professor of American Studies and History, Dissertation Director Teresa Anne Murphy, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member John Michael Vlach, Professor of American Studies and of Anthropology, Committee Member ii Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank the committee members for expert guidance that was probing and humbling as well as encouraging. Each of them handled the challenges of working with an older student with grace and aplomb. Another of the great pleasures of this dissertation process was working in a variety of archives with wonderful facilities and staff. It was a privilege to meet some of the people who are stewards of records in those repositories. -

Marcus Garvey Civil Rights Activist (1887–1940)

Marcus Garvey Civil Rights Activist (1887–1940) SECTION ONE SOURCE: https://www.biography.com/people/marcus-garvey-9307319 NOTE: Images and textboxes not in the original source of this biography. Marcus Garvey was a proponent of the Black Nationalism and Pan- Africanism movements, inspiring the Nation of Islam and the Rastafarian movement. Synopsis Born in Jamaica, Marcus Garvey was an orator for the Black Nationalism and Pan-Africanism movements, to which end he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League. Garvey advanced a Pan-African philosophy which inspired a global mass movement, known as Garveyism. Garveyism would eventually inspire others, from the Nation of Islam to the Rastafari movement. Marcus Garvey Early Life Social activist Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr. was born on August 17, 1887, in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica. Self-educated, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association, dedicated to promoting African-Americans and resettlement in Africa. In the United States he launched several businesses to promote a separate black nation. After he was convicted of mail fraud and “A people without the knowledge of deported back to Jamaica, he continued his their past history, origin and culture work for black repatriation to Africa. Marcus Mosiah Garvey was the last of 11 is like a tree without roots.” children born to Marcus Garvey, Sr. and Sarah ― Marcus Garvey Jane Richards. His father was a stone mason, and his mother a domestic worker and farmer. Page 1 of 11 Garvey, Sr. was a great influence on Marcus, who once described him as "severe, firm, determined, bold, and strong, refusing to yield even to superior forces if he believed he was right." His father was known to have a large library, where young Garvey learned to read. -

The Creation of Enemies: Investigating Conservative Environmental Polarization, 1945-1981

The Creation of Enemies: Investigating Conservative Environmental Polarization, 1945-1981 by Adam Duane Orford A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel Kammen, Co-Chair Professor Katherine O’Neill, Co-Chair Professor Alastair Iles Professor Rebecca McLennan Spring 2021 © 2021 Adam Duane Orford all rights reserved Abstract The Creation of Enemies: Investigating Conservative Environmental Polarization, 1945-1981 by Adam Duane Orford Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources University of California, Berkeley Professors Daniel Kammen and Katherine O’Neill, Co-Chairs This Dissertation examines the history of the conservative relationship with environmentalism in the United States between 1945 and 1981. In response to recent calls to bring the histories of U.S. political conservatism and environmentalism into conversation with each other, it investigates postwar environmental political history through the lens of partisan and ideological polarization and generates a research agenda for the field. It then contributes three new studies in conservative environmental politics: an analysis of the environmental rhetoric of a national business magazine; the legislative history of the first law to extend the power of the federal government to fight air pollution; and a history of the conservative response to Earth Day. It concludes that conservative opposition to environmentalism in the United States has been both ideological and situational. 1 Acknowledgements My most profound gratitude… To my parents, who always encouraged me to pursue my passions; To my wife, Dax, who knows what it takes to write a dissertation (I love you); And to all of the many people I have learned from at U.C. -

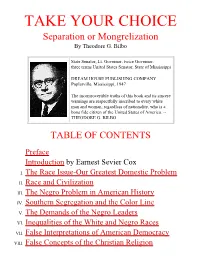

TAKE YOUR CHOICE Separation Or Mongrelization by Theodore G

TAKE YOUR CHOICE Separation or Mongrelization By Theodore G. Bilbo State Senator, Lt. Governor, twice Governor, three terms United States Senator, State of Mississippi DREAM HOUSE PUBLISHING COMPANY Poplarville, Mississippi, 1947 The incontrovertible truths of this book and its sincere warnings are respectfully inscribed to every white man and woman, regardless of nationality, who is a bona fide citizen of the United States of America. -- THEODORE G. BILBO TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction by Earnest Sevier Cox I. The Race Issue-Our Greatest Domestic Problem II. Race and Civilization III. The Negro Problem in American History IV. Southern Segregation and the Color Line V. The Demands of the Negro Leaders VI. Inequalities of the White and Negro Races VII. False Interpretations of American Democracy VIII. False Concepts of the Christian Religion IX. The Campaign for Complete Equality X. Astounding Revelations to White America XI. The Springfield Plan and Such XII. The Dangers of Amalgamation XIII. Physical Separation-Proper Solution to the Race Problem XIV. Outstanding Advocates of Separation XV. The Negro Repatriation Movement XVI. Standing at the Crossroads Take Your Choice Separation or Mongrelization By Theodore G. Bilbo PREFACE THE TITLE of this book is TAKE YOUR CHOICE - SEPARATION OR MONGRELlZATION. Maybe the title should have been "You Must Take or You Have Already Taken Your Choice-Separation or Mongrelization," but regardless of the name of this book it is really and in fact a S.O.S call to every white man and white woman within the United States of America for immediate action, and it is also a warning of equal importance to every right- thinking and straight-thinking American Negro who has any regard or respect for the integrity of his Negro blood and his Negro race. -

Symbols and Abbreviations

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS Repository Symbols The original locations of documents that appear in the text are described by symbols. The guide used for American repositories has been Symbols of American Libraries, eleventh edition (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1976). Foreign repositories and collections have been assigned symbols that conform to the institutions' own usage. In some cases, however, it has been necessary to formulate acronyms. Acronyms have been created for private manuscript collections as well. Repositories ADSL Archives of the Department of State, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Monrovia, Liberia AFRC Federal Archives and Records Center, East Point, Georgia ANSOM Archives Nationales, Section d'Outre-Mer, Paris ATT Hollis Burke Frissell Library, Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama DJ-FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation, United States Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. DLC Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. DNA National Archives, Washington, D.C. RG 16 Records of the Office of the Secretary of Agri- culture RG 28 Records of the Post Office Department RG 32 Records of the United States Shipping Board RG 38 Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations RG 41 Records of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation li THE MARCUS GARVEY AND UNIA PAPERS RG 59 General Records of the Department of State RG 60 General Records of the Department of Justice RG 65 Records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation RG 85 Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service RG 165 Records of the War Department, -

Jackson Pp001-092

1 A Scientific Conspiracy Founded in 1970, the Behavioral Genetics Association (BGA) is dedicated to the “scientific study of the interrelationship of genetic mechanisms and behavior, both human and animal.”1 Like many profes- sional organizations, the BGA has the president of the association address the banquet at the annual meeting. In 1995 the president of the BGA was Florida State University psychologist Glayde Whitney, who had been on the editorial board of the association’s journal, Behavior Genetics, for a number of years and had an established research program investigating taste preferences in mice. His address, “Twenty-five Years of Behavioral Genetics,” started in a typical fashion for such occasions, as Whitney re- counted his training at the University of Minnesota and his arrival at Florida State University in 1970, where he established his “mouse lab” and began his lifelong research program. The address soon took a differ- ent turn, however, as Whitney began discussing the racial basis of crime. Such an investigation had been hampered, he declared, by the dogma that the environment determined all behavioral traits and by the taboo against scientific research into race. Whitney decried these trends, as he saw them: “The Marxist-Lysenkoist denial of genetics, the emphasis on envi- ronmental determinism for all things human . [represents an] invasion of left-liberal political sentiment [that] has been so extensive that many of us think that way without realizing it.” Whitney’s invocation of Ly- senkoism was a quick one-two punch for his audience of geneticists. First, it called up the discredited doctrine of the inheritance of acquired char- acteristics.