Sample Chapter: NOT for CITATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meet Charles Koch's Brain.Pdf

“ Was I, perhaps, hallucinating? Or was I, in reality, nothing more than a con man, taking advantage of others?” —Robert LeFevre BY MARK known as “Rampart College”), School] is where I was first exposed which his backers wanted to turn in-depth to such thinkers as Mises AMES into the nation’s premier libertarian and Hayek.” indoctrination camp. Awkwardly for Koch, Freedom What makes Charles Koch tick? There are plenty of secondary School didn’t just teach radical Despite decades of building the sources placing Koch at LeFevre’s pro-property libertarianism, it also nation’s most impressive ideological Freedom School. Libertarian court published a series of Holocaust- and influence-peddling network, historian Brian Doherty—who has denial articles through its house from ideas-mills to think-tanks to spent most of his adult life on the magazine, Ramparts Journal. The policy-lobbying machines, the Koch Koch brothers’ payroll—described first of those articles was published brothers only really came to public LeFevre as “an anarchist figure in 1966, two years after Charles prominence in the past couple of who stole Charles Koch’s heart;” Koch joined Freedom School as years. Since then we’ve learned a Murray Rothbard, who co-founded executive, trustee and funder. lot about the billionaire siblings’ the Cato Institute with Charles “Evenifoneweretoaccept vast web of influence and power in Koch in 1977, wrote that Charles themostextremeand American politics and ideas. “had been converted as a youth to exaggeratedindictment Yet, for all that attention, there libertarianism by LeFevre.” ofHitlerandthenational are still big holes in our knowledge But perhaps the most credible socialistsfortheiractivities of the Kochs. -

HOLOCAUST DENIAL* Denial of the Truth of the Holocaust Comes in Three Modes. One Mode Is Seldom Recognized: Bracketing the SHOAH with Other Mass Murders in History

HOLOCAUST DENIAL* Denial of the truth of the Holocaust comes in three modes. One mode is seldom recognized: bracketing the SHOAH with other mass murders in history. This mode of generalization flattens out the specificity and denies the uniqueness of the Holocaust. Unpleasant ethical, moral and theological issues are thereby stifled. The Holocaust is swallowed up in the mighty river of wickedness and mass murder that has characterized human history since the mind of man runneth not to the contrary. From the balcony - a perch often preferred by the privileged and/or educated - all violence down there seems remote. A second mode of denial is. encountered as an expression of Jewish preciousness. More or less bluntly, the position is taken that the Holocaust cannot be understood by a person who is not a Jew. This is a very dangerous posture, for by it the gentile - whether perpetrator or spectator - is home free. Why should he accept responsibility for an action whose significance, he is assured by the victims, is outside his universe of discourse? The third mode of denial, in nature and expression more often in the public view, is intellectually less interesting. Like the thought world of its purveyers, it is marked by banality. What interest does a thinking person have in debating whether or not the earth is flat? Nevertheless, the third mode of denial is alive and well. In large areas dominated by Christian, Jewish or Muslim fundamentalism, the facts are denied. In pristine condition, none of the three great monotheistic religions has need to deny the *by Franklin H. -

Petuaohingtenposi Book World

petuaohingtenposi Book World 1.KG1;01 , MIL LK 13111 Itt3 SI•1111-li 11:41 `11,3 ilia/. 1_0 471 emu 1.; ist 4Fr, alusTNArION av PiAIAN ■LLOArRIJ FUR FOR THE WASHPNIGFON POSt • Sink(DAY„ .4.11_4( k.„. 1993 Antisemitic History: The Fate of the 6 Million DENYING THE HOLOCAUST ment literally steals millions of dollars from The Growing Assault on you and other U.S. taxpayers. The thief is the Truth and Memory corrupt, bankrupt government of Israel . By Deborah E. Upstadt And the theft is perpetrated primarily through Free Press. 278 pp. $22.95 the clever use of the Greatest Lie in all his- tory—the lie of the 'Holocaust.' " By Paul Johnson This particular statement was put out by an organization called the Institute for Historical NTISEMITISM is one of the oldest Research, a pseudo-academic body that has and most persistent of human delu• been one of the most energetic exponents of sions. Some Jews resignedly believe Holocaust-denial. In 1979 it held the first "Re- it is ineradicable. It is protean and visionist Convention" in Los Angeles. The takes countless different forms, so that it is MR had been founded the year before by peculiarly resistant to empirical disproof: Lewis Brandon, who was born in 1951 in Nailed in one shape, it instantly reappears in Northern Ireland and has a long record of fas- another, often contradictory one. The fact of cist activities on both sides of the Atlantic. His the Holocaust ought to have ended antisem- real name was William David McCalden, itism everywhere, forever. -

Pioneer's Big Lie

COMMENTARIES PIONEER'S BIG LIE Paul A. Lombardo* In this they proceeded on the sound principle that the magnitude of a lie always contains a certain factor of credibility, since the great masses of the people in the very bottom of their hearts tend to be corrupted rather than consciously and purposely evil, and that, therefore, in view of the primitive simplicity of their minds, they more easily fall a victim to a big lie than to a little one, since they themselves lie in little things, but would be ashamed of lies that were too big. Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf' In the spring of 2002, I published an article entitled "The American Breed" Nazi Eugenics and the Origins of the Pioneer Fund as part of a symposium edition of the Albany Law Review.2 My objective was to present "a detailed analysis of the.., origins of the Pioneer Fund"3 and to show the connections between Nazi eugenics and one branch of the American eugenics movement that I described as purveying "a malevolent brand of biological determinism."4 I collected published evidence on the Pioneer Fund's history and supplemented it with material from several archival collections-focusing particularly on letters and other documents that explained the relationship between Pioneer's first President, 'Paul A. Lombardo, Ph.D., J.D., Director, Program in Law and Medicine, University of Virginia Center for Bioethics. I ADOLF HITLER, MEIN KAMPF 231 (Ralph Manheim trans., Houghton Mifflin Co. 1971) (1925). 2 Paul A. Lombardo, "The American Breed" Nazi Eugenics and the Origins of the Pioneer Fund, 65 ALB. -

The Sociopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America

Voces Novae Volume 11 Article 3 2019 Engineering Mankind: The oS ciopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America Megan Lee [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Part of the American Politics Commons, Bioethics and Medical Ethics Commons, Genetics and Genomics Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Megan (2019) "Engineering Mankind: The ocS iopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America," Voces Novae: Vol. 11, Article 3. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lee: Engineering Mankind: The Sociopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America Engineering Mankind: The Sociopolitical Impact of Eugenics in America Megan Lee “It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind…Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”1 This statement was made by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. while presenting the court’s majority opinion on the sterilization of a seventeen-year old girl in 1927. The concept of forced sterilization emerged during the American Eugenics Movement of the early 20th century. In 1909, California became one of the first states to introduce eugenic laws which legalized the forced sterilization of those deemed “feeble-minded.” The victims were mentally ill patients in psychiatric state hospitals, individuals who suffered from epilepsy and autism, and prisoners with criminal convictions, all of whom were forcibly castrated. -

Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010

Description of document: Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010 Requested date: 13-May-2010 Released date: 03-December-2010 Posted date: 09-May-2011 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Officer Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL US Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Notes: This index lists documents the State Department has released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) The number in the right-most column on the released pages indicates the number of microfiche sheets available for each topic/request The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Anthropology and the Racial Politics of Culture

ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE RACIAL POLITICS OF CULTURE Lee D. Baker Anthropology and the Racial Politics of Culture Duke University Press Durham and London ( 2010 ) © 2010 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Warnock with Magma Compact display by Achorn International, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Dedicated to WILLIAM A. LITTLE AND SABRINA L. THOMAS Contents Preface: Questions ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 (1) Research, Reform, and Racial Uplift 33 (2) Fabricating the Authentic and the Politics of the Real 66 (3) Race, Relevance, and Daniel G. Brinton’s Ill-Fated Bid for Prominence 117 (4) The Cult of Franz Boas and His “Conspiracy” to Destroy the White Race 156 Notes 221 Works Cited 235 Index 265 Preface Questions “Are you a hegro? I a hegro too. Are you a hegro?” My mother loves to recount the story of how, as a three year old, I used this innocent, mis pronounced question to interrogate the garbagemen as I furiously raced my Big Wheel up and down the driveway of our rather large house on Park Avenue, a beautiful tree-lined street in an all-white neighborhood in Yakima, Washington. It was 1969. The Vietnam War was raging in South- east Asia, and the brutal murders of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Bobby and John F. Kennedy hung like a pall over a nation coming to grips with new formulations, relations, and understand- ings of race, culture, and power. -

Totalitarian Dynamics, Colonial History, and Modernity: the US South After the Civil War

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

The North American White Supremacist Movement: an Analysis Ofinternet Hate Web Sites

wmTE SUPREMACIST HATE ON THE WORLD WIDE WEB "WWW.HATE.ORG" THE NORTH AMERICAN WIDTE SUPREMACIST MOVEMENT: AN ANALYSIS OF INTERNET HATE WEB SITES By ALLISON M. JONES, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School ofGraduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master ofArts McMaster University © Copyright by Allison M. Jones, October 1999 MASTER OF ARTS (1999) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Sociology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: "www.hate.org" -- The North American White Supremacist Movement: An Analysis ofInternet Hate Web Sites AUTHOR: Allison M. Jones, B.A. (York University) SUPERVISOR: Professor V. Satzewich NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 220 ii Abstract This thesis is a qualitative study ofNorth American white supremacist organisations, and their Internet web sites. Major issues framing the discussion include identity and racism. The thesis takes into consideration Goffman's concepts of'impression management' and 'presentation ofself as they relate to the web site manifestations of 'white power' groups. The purpose ofthe study is to analyse how a sample ofwhite supremacist groups present themselves and their ideologies in the context ofthe World Wide Web, and what elements they use as a part oftheir 'performances', including text, phraseology, and images. Presentation ofselfintersects with racism in that many modern white supremacists use aspects ofthe 'new racism', 'coded language' and'rearticulation' in the attempt to make their fundamentally racist worldview more palatable to the mainstream. Impression management techniques are employed in a complex manner, in either a 'positive' or 'negative' sense. Used positively, methods may be employed to impress the audience with the 'rationality' ofthe arguments and ideas put forth by the web site creators. -

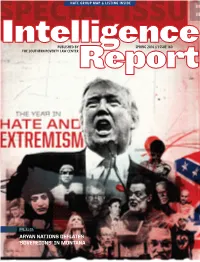

Aryan Nations Deflates

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men. -

The American Militia Phenomenon: a Psychological

THE AMERICAN MILITIA PHENOMENON: A PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILE OF MILITANT THEOCRACIES ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Political Science ____________ by © Theodore C. Allen 2009 Summer 2009 PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Publication Rights ...................................................................................................... iii Abstract....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER I. Introduction.............................................................................................. 1 II. Literature Review of the Modern Militia Phenomenon ........................... 11 Government Sources .................................................................... 11 Historical and Scholarly Works.................................................... 13 Popular Media .............................................................................. 18 III. The History of the Militia in America...................................................... 23 The Nexus Between Religion and Race ....................................... 28 Jefferson’s Wall of Separation ..................................................... 31 Revolution and the Church.......................................................... -

How White Supremacist Groups Have Embraced Crowdfunding

From Classifieds to Crypto: How White Supremacist Groups Have Embraced Crowdfunding ALEX NEWHOUSE Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism www.middlebury.edu/institute/academics/centers-initiatives/ctec The Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism (CTEC) conducts in-depth research on terrorism and other forms of extremism. Formerly known as the Monterey Terrorism Research and Education Program, CTEC collaborates with world-renowned faculty and their graduate students in the Middlebury Institute’s Nonproliferation and Terrorism Studies degree program. CTEC’s research informs private, government, and multilateral institutional understanding of and responses to terrorism threats. Middlebury Institute for International Studies at Monterey www.miis.edu The Middlebury Institute for International Studies at Monterey provides international professional education in areas of critical importance to a rapidly changing global community, including international policy and management, translation and interpretation, language teaching, sustainable development, and nonproliferation. We prepare students from all over the world to make a meaningful impact in their chosen fields through degree programs characterized by immersive and collaborative learning, and opportunities to acquire and apply practical professional skills. Our students are emerging leaders capable of bridging cultural, organizational, and language divides to produce sustainable, equitable solutions to a variety of global challenges. Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism Middlebury Institute of International Studies 460 Pierce Street Monterey, CA 93940, USA Tel: +1 (831) 647-4634 The views, judgments, and conclusions in this report are the sole representations of the authors and do not necessarily represent either the official position or policy or bear the endorsement of CTEC or the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey.