SIR HARRISON BIRTWISTLE on HIS SONGS Interviewed by Stephan Meier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Roots of Birtwistle's Theatrical Expression

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89534-7 - Harrison Birtwistle’s Operas and Music Theatre David Beard Excerpt More information 1 The roots of Birtwistle’s theatrical expression: from Pantomime to Down by the Greenwood Side With six major operas, around eight music dramas, and a body of incidental music to his name, Harrison Birtwistle has made a significant contribution to contemporary opera and music theatre during a period that spans more than forty years. This study is concerned not only to reflect the importance of these stage works by examining them in some detail but also to convey their varied musical and intellectual worlds. Previous studies have rightly focused on Birtwistle’s perennial concerns, such as myth, ritual, cyclical journeys, varied repetition, verse–refrain structures, instrumental role-play, layers and lines.1 These characteristics highlight consistency throughout Birtwistle’s oeuvre and are a mark of his formalist stance. By contrast, this book is motivated by a belief that the stage works – in which instrumental and physical drama, song and narrative are combined – demand interpre- tation from multiple, inter-disciplinary perspectives. While not denying obvious or important relations between works, what follows is rather more focused on differences: Birtwistle’s choice of contrasting narrative subjects, his collaborations with nine librettists, his varied pre-compositional ideas and working methods, his experience with different directors, producers and others, all distinguish one stage work from another. A recurring theme is therefore a consideration of ways in which Birtwistle’s initial concepts are informed, altered or conveyed differently in each case. Moreover, as ideas evolve, from the composer’s musical sketches to the final production, mul- tiple meanings accrue that are particular to each drama. -

Media Release Wolfgang Rihm Is the LUCERNE

Media Release Wolfgang Rihm Is the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY’s New Artistic Director Matthias Pintscher Named Principal Conductor Lucerne, 04 September 2015 . Starting in the summer of 2016, the German composer Wolfgang Rihm will assume overall artistic directorship of the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY. The conductor and composer Matthias Pintscher will support him as Principal Conductor and will be responsible each summer for a central Academy program; he will additionally focus on developing the Academy Orchestra. Both contracts are for a period of five years. The founder of the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY, Pierre Boulez, will continue to remain in close dialogue with Wolfgang Rihm, Matthias Pintscher, and the Festival team as Honorary President of the Academy. For twelve years the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY has been regarded as a unique international educational campus in the field of contemporary classical music of the 20th and 21st centuries. It offers continuing training not only for some 120 instrumentalists between 18 and 32 years of age but also for young directors and composers. “I am extremely delighted that in the person of Wolfgang Rihm a leading figure of contemporary music will be taking over artistic leadership of the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY,” remarks Michael Haefliger, LUCERNE FESTIVAL’s Executive and Artistic Director. “On the strength of his experience and his knowledge in connection with the Academy, Wolfgang Rihm will be in a position to establish new directions for linking creativity with effective ways of working together for young instrumentalists, conductors, and composers. This summer Matthias Pintscher has returned for a third time as a teacher and conductor to help shape the Academy’s work in marvelous ways, as seen for example in the recent “Day for Pierre Boulez”. -

Klsp2018iema Broschuere.Indd

KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY IN TIROL. REBECCA SAUNDERS COMPOSER IN RESIDENCE. 15TH EDITION 29.08. – 09.09.2018 KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY 2018 KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ is celebrating its 25th anniversary in 2018. The annual Tyrolean festival of contemporary music provides a stage for performances, encounters, and for the exploration and exchange of new musical ideas. With a different thematic focus each year, KLANGSPUREN aims to present a survey of the fascinating, diverse panorama that the music of our time boasts. KLANGSPUREN values open discourse, participation, and partnership and actively seeks encounters with locals as well as visitors from abroad. The entire beautiful region of Tyrol unfolds as the festival’s playground, where the most cutting-edge and modern forms of music as well as many young composers and musicians are presented. On the occasion of its own milestone anniversary – among other anniversaries that KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ 2018 will be celebrating this year – the 25th edition of the festival has chosen the motto „Festivities. Places.“ (in German: „Feste. Orte.“). The program emphasizes projects and works that focus on aspects of celebrations, festivities, rituals, and events and have a specific reference to place and situation. KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY is celebrating its 15th anniversary. The Academy is an offshoot of the renowned International Ensemble Modern Academy (IEMA) in Frankfurt and was founded in the same year as IEMA, in 2003. The Academy is central to KLANGSPUREN and has developed into one of the most successful projects of the Tyrolean festival for new music. The high standards of the Academy are vouched for by prominent figures who have acted as Composers in Residence: György Kurtág, Helmut Lachenmann, Steve Reich, Benedict Mason, Michael Gielen, Wolfgang Rihm, Martin Matalon, Johannes Maria Staud, Heinz Holliger, George Benjamin, Unsuk Chin, Hans Zender, Hans Abrahamsen, Wolfgang Mitterer, Beat Furrer, Enno Poppe, and most recently in 2017, Sofia Gubaidulina. -

With a Rich History Steeped in Tradition, the Courage to Stand Apart and An

With a rich history steeped in tradition, the courage to stand apart and an enduring joy of discovery, the Wiener Symphoniker are the beating heart of the metropolis of classical music, Vienna. For 120 years, the orchestra has shaped the special sound of its native city, forging a link between past, present and future like no other. In Andrés Orozco-Estrada - for several years now an adopted Viennese - the orchestra has found a Chief Conductor to lead this skilful ensemble forward from the 20-21 season onward, and at the same time revisit its musical roots. That the Wiener Symphoniker were formed in 1900 of all years is no coincidence. The fresh wind of Viennese Modernism swirled around this new orchestra, which confronted the challenges of the 20th century with confidence and vision. This initially included the assured command of the city's musical past: they were the first orchestra to present all of Beethoven's symphonies in the Austrian capital as one cycle. The humanist and forward-looking legacy of Beethoven and Viennese Romanticism seems tailor-made for the Symphoniker, who are justly leaders in this repertoire to this day. That pioneering spirit, however, is also evident in the fact that within a very short time the Wiener Symphoniker rose to become one of the most important European orchestras for the premiering of new works. They have given the world premieres of many milestones of music history, such as Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony, Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-Lieder, Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand and Franz Schmidt's The Book of the Seven Seals - concerts that opened a door onto completely new worlds of sound and made these accessible to the greater masses. -

AMERICAN ACADEMY in ROME PRESENTS the SCHAROUN ENSEMBLE CONCERT SERIES 14-16 JANUARY 2011 at VILLA AURELIA Exclusive Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 11, 2011 AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME PRESENTS THE SCHAROUN ENSEMBLE CONCERT SERIES 14-16 JANUARY 2011 AT VILLA AURELIA Exclusive Concert Dates in Italy for the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin Courtesy of the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin Rome – The American Academy in Rome is pleased to present a series of three concerts by one of Germany’s most distinguished chamber music ensembles, the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin. Comprised of members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin specializes in a repertoire of Classical, Romantic, 20th century Modernist, and contemporary music. 2011 marks the third year of collaboration between the Ensemble and the American Academy in Rome, which includes performances of work by current Academy Fellows in Musical Composition Huck Hodge and Paul Rudy, as well as 2009 Academy Fellow Keeril Makan. Featuring soprano Rinnat Moriah, the Ensemble will also perform music by Ludwig van Beethoven, John Dowland, Antonin Dvořák, Sofia Gubaidulina, Heinz Holliger, Luca Mosca, and Stefan Wolpe. The concerts are free to the public and will take place at the Academy’s Villa Aurelia from 14-16 January 2011. Event: Scharoun Ensemble Berlin (preliminary program*) 14 January at 9pm – Ludwig van Beethoven, John Dowland, Huck Hodge, and Stefan Wolpe 15 January at 9pm – Sofia Gubaidulina, Huck Hodge, Heinz Holliger and Keeril Makan 16 January at 11am – Antonin Dvořák, Luca Mosca, and Paul Rudy *subject to change Location: Villa Aurelia, American Academy in Rome Largo di Porta San Pancrazio, 1 Scharoun Ensemble Berlin The Scharoun Ensemble Berlin was founded in 1983 by members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. -

Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018

The 100% Unofficial Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 O Guia Rápido 100% Não-Oficial do Eurovision Song Contest 2018 for Commentators Broadcasters Media & Fans Compiled by Lisa-Jayne Lewis & Samantha Ross Compilado por Lisa-Jayne Lewis e Samantha Ross with Eleanor Chalkley & Rachel Humphrey 2018 Host City: Lisbon Since the Neolithic period, people have been making their homes where the Tagus meets the Atlantic. The sheltered harbour conditions have made Lisbon a major port for two millennia, and as a result of the maritime exploits of the Age of Discoveries Lisbon became the centre of an imperial Portugal. Modern Lisbon is a diverse, exciting, creative city where the ancient and modern mix, and adventure hides around every corner. 2018 Venue: The Altice Arena Sitting like a beautiful UFO on the banks of the River Tagus, the Altice Arena has hosted events as diverse as technology forum Web Summit, the 2002 World Fencing Championships and Kylie Minogue’s Portuguese debut concert. With a maximum capacity of 20000 people and an innovative wooden internal structure intended to invoke the form of Portuguese carrack, the arena was constructed specially for Expo ‘98 and very well served by the Lisbon public transport system. 2018 Hosts: Sílvia Alberto, Filomena Cautela, Catarina Furtado, Daniela Ruah Sílvia Alberto is a graduate of both Lisbon Film and Theatre School and RTP’s Clube Disney. She has hosted Portugal’s edition of Dancing With The Stars and since 2008 has been the face of Festival da Cançao. Filomena Cautela is the funniest person on Portuguese TV. -

Zug (8Th) and Basel (10Th) Rank Far Ahead of Lausanne (36Th), Bern (38Th), Zurich (41St), Lugano (53Rd), and Geneva (69Th) in the Expat City Ranking 2019

• Zug (8th) and Basel (10th) rank far ahead of Lausanne (36th), Bern (38th), Zurich (41st), Lugano (53rd), and Geneva (69th) in the Expat City Ranking 2019. • Based on the ranking, Taipei, Kuala Lumpur, Ho Chi Minh City, Singapore, Montréal, Lisbon, Barcelona, Zug, The Hague, and Basel are the best cities to move to in 2020. • Kuwait City (82nd), Rome, Milan, Lagos (Nigeria), Paris, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Lima, New York City, and Yangon (73rd) are the world’s worst cities. Munich, 3 December 2019 — Seven Swiss cities are featured in the Expat City Ranking 2019 by InterNations, the world’s largest expat community with more than 3.5 million members. They all rank among the top 20 in the world for the quality of life, receiving mostly high marks for safety, local transportation, and the environment. On the other hand, expats struggle to get settled, with Zurich and Bern even ranking among the world’s worst cities in this regard. While the local cost of living is rated negatively across the board, the performance of the Swiss cities varies more in the Finance & Housing and Urban Work Life Indices. The Expat City Ranking is based on the annual Expat Insider survey by InterNations, which is with more than 20,000 respondents in 2019 one of the most extensive surveys about living and working abroad. In 2019, 82 cities around the globe are analyzed in the survey, offering in-depth information about five areas of expat life: Quality of Urban Living, Getting Settled, Urban Work Life, Finance & Housing, and Local Cost of Living. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Brand Guidelines Version 5-2017/2018

BRAND GUIDELINES VERSION 5-2017/2018 OPERATED BY EBU THE EUROVISION SONG CONTEST - “ A SIMPLE IDEA THAT HAS SUCCEEDED. “MARCEL BEZENÇON DIRECTOR OF THE EBU (1950-1970) AND INITIATOR OF THE EUROVISION SONG CONTEST — 2 THE NAME The name of the event in public communication is always Eurovision Song Contest. For headlines and on social media, but only when practical limitations such as character limits apply, the event can be referred to as Eurovision. The abbreviation ESC may only be used for internal communications, as it is largely unknown to the public. In some countries, the Eurovision Song Contest has a translated name, such as Eurovisie Songfestival (Dutch) or Grand Prix Eurovision de la Chanson (French). These names may be used, but only in national communication. EUROVISION SONG CONTEST BRAND GUIDELINES — 3 THE LOGO Until the 2003 Eurovision Song Contest, each Host Broadcaster designed its own logo for the contest. In 2004, the EBU introduced a generic logo, to be accompanied by a theme and supporting artwork on a year-by-year basis. The logo was designed by London-based agency JM Enternational. In 2014, the EBU introduced a revamp, the current version of the logo. It was revamped by Storytegic and implemented in collaboration with Scrn. Eurovision is set in custom typograpy Song Contest is set in Gotham Bold with +25% letter spacing and +25% word spacing EUROVISION SONG CONTEST BRAND GUIDELINES — 4 THE ECO-SYSTEM The Eurovision Song Contest generic identity consists of an eco-system with four different applications, shown below. Some basic guidelines: Ÿ The generic logo can only be used by EBU and its partners; Ÿ The event logo can only be used for a particular event by the EBU, Host Broadcaster, Participating Broadcasters and Event Partners (sponsors); Ÿ A national logo can only be used by the EBU, its partners and each respective Participating Broadcaster; Ÿ The flag heart can only be used for illustrative purposes (e.g. -

Gotthard Panorama Express. Sales Manual 2021

Gotthard Panorama Express. Sales Manual 2021. sbb.ch/en/gotthard-panorama-express Enjoy history on the Gotthard Panorama Express to make travel into an experience. This is a unique combination of boat and train journeys on the route between Central Switzerland and Ticino. Der Gotthard Panorama Express: ì will operate from 1 May – 18 October 2021 every Tuesday to Sunday (including national public holidays) ì travels on the line from Lugano to Arth-Goldau in three hours. There are connections to the Mount Rigi Railways, the Voralpen-Express to Lucerne and St. Gallen and long-distance trains towards Lucerne/ Basel, Zurich or back to Ticino via the Gotthard Base Tunnel here. ì with the destination Arth-Goldau offers, varied opportunities; for example, the journey can be combined with an excursion via cog railway to the Rigi and by boat from Vitznau. ì runs as a 1st class panorama train with more capacity. There is now a total of 216 seats in four panorama coaches. The popular photography coach has been retained. ì requires a supplement of CHF 16 per person for the railway section. The supplement includes the compulsory seat reservation. ì now offers groups of ten people or more a group discount of 30% (adjustment of group rates across the whole of Switzerland). 2 3 Table of contents. Information on the route 4 Route highlights 4–5 Journey by boat 6 Journey on the panorama train 7 Timetable 8 Train composition 9 Fleet of ships 9 Prices and supplements 12 Purchase procedure 13 Services 14 Information for tour operators 15 Team 17 Treno Gottardo 18 Grand Train Tour of Switzerland 19 2 3 Information on the route. -

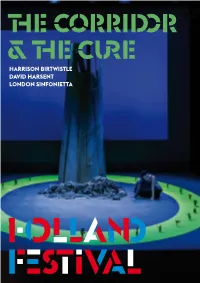

The-Corridor-The-Cure-Programma

thE Corridor & thE curE HARRISON BIRTWISTLE DAVID HARSENT LONDON SINFONIETTA INHOUD CONTENT INFO 02 CREDITS 03 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA EN IK 05 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA AND ME 10 OVER DE ARTIESTEN 14 ABOUT THE ARTISTS 18 BIOGRAFIEËN 16 BIOGRAPHIES 20 HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2016 24 WORD VRIEND BECOME A FRIEND 26 COLOFON COLOPHON 28 1 INFO DO 9.6, VR 10.6 THU 9.6, FRI 10.6 aanvang starting time 20:30 8.30 pm locatie venue Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ duur running time 2 uur 5 minuten, inclusief een pauze 2 hours 5 minutes, including one interval taal language Engels met Nederlandse boventiteling English with Dutch surtitles inleiding introduction door by Ruth Mackenzie (9.6), Michel Khalifa (10.6) 19:45 7.45 pm context za 11.6, 14:00 Sat 11.6, 2 pm Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam Workshop Spielbar: speel eigentijdse muziek play contemporary music 2 Tim Gill, cello CREDITS Helen Tunstall, harp muziek music orkestleider orchestra manager Harrison Birtwistle Hal Hutchison tekst text productieleiding production manager David Harsent David Pritchard regie direction supervisie kostuums costume supervisor Martin Duncan Ilaria Martello toneelbeeld, kostuums set, costume supervisie garderobe wardrobe supervisor Alison Chitty Gemma Reeve licht light supervisie pruiken & make-up Paul Pyant wigs & make-up supervisor Elizabeth Arklie choreografie choreography Michael Popper voorstellingsleiding company stage manager regie-assistent assistant director Laura Thatcher Marc Callahan assistent voorstellingsleiding sopraan soprano deputy stage manager Elizabeth Atherton -

The Cultural Politics of Eurovision: a Case Study of Ukraine’S Invasion in 2014 Against Their Eurovision Win in 2016

Claremont-UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union Volume 2017 Article 6 9-12-2017 The ulturC al Politics of Eurovision: A Case Study of Ukraine’s Invasion in 2014 Against Their Eurovision Win in 2016 Jordana L. Cashman Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/urceu Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Cashman, Jordana L. (2017) "The ulturC al Politics of Eurovision: A Case Study of Ukraine’s Invasion in 2014 Against Their Eurovision Win in 2016," Claremont-UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union: Vol. 2017, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/urceu.201701.06 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/urceu/vol2017/iss1/6 This Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Claremont-UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont–UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union 45 4 The Cultural Politics of Eurovision: A Case Study of Ukraine’s Invasion in 2014 Against Their Eurovision Win in 2016 Jordana L. Cashman Brigham Young University Abstract Politics is officially banned from Eurovision, and songs that are too political can be prevented from being performed. However, the complete separation of culture and politics is impossible, and cultural performances often carry both indirect and explicit political mes- sages.