Achieving the Copyright Equilibrium: How Fair Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'expérience De Création De Jeux Vidéo En Amateur Travailler Son

Université de Liège Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres Département Médias, Culture et Communication L’expérience de création de jeux vidéo en amateur Travailler son goût pour l’incertitude Thèse présentée par Pierre-Yves Hurel en vue de l’obtention du titre de Docteur en Information et Communication sous la direction de Christine Servais Année académique 2019-2020 À Anne-Lyse, à notre aventure, à nos traversées, à nos horizons. À Charlotte, à tes cris de l’oie, à tes sourires en coin, à tes découvertes. REMERCIEMENTS Écrire une thèse est un acte pétri d’incertitudes, que l’auteur cherche à maîtriser, cadrer et contrôler. J’ai eu le bonheur d’être particulièrement bien accompagné dans cette pratique du doute. Seul face à mon document, j’étais riche de toutes les discussions qui ont jalonné mes années de doctorat. Je souhaite particulièrement remercier mes interlocuteurs pour leur générosité : - Christine Servais, pour sa direction minutieuse, sa franchise, sa bienveillance, ses conseils et son écoute. - Les membres du jury pour avoir accepté de me livrer leur analyse du présent travail. - Tous les membres du Liège Game Lab pour leur intelligence dans leur participation à notre collectif de recherche, pour leur capacité à échanger de manière constructive et pour leur humour sans égal. Merci au Docteure Barnabé (chercheuse internationale et coauteure de cafés-thèse fondateurs), au Docteure Delbouille (brillante sitôt qu’on l’entend), au Docteur Dupont (titulaire d’un double doctorat en lettres modernes et en élégance), au Docteur Dozo (dont le sens du collectif a tant permis), au futur Docteur Krywicki (prolifique en tout domaine), au futur Docteur Houlmont (dont je ne connais qu’un défaut) et au futur Docteur Bashandy (dont le vécu et les travaux incitent à l’humilité). -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Title a Rewards-Based Crowdfunding

Title A Rewards-Based Crowdfunding Platform for Chinese Doujin Fans and Doujin Creators Sub Title Author 劉, 通(Liu, Tong) 中村, 伊知哉(Nakamura, Ichiya) Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2015 Jtitle Abstract Notes 修士学位論文. 2015年度メディアデザイン学 第431号 Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-0000201 5-0431 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって 保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守してご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Master's Thesis Academic Year 2015 A Rewards-Based Crowdfunding Platform for Chinese Doujin Fans and Doujin Creators Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University Tong Liu A Master's Thesis submitted to Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of Media Design Tong Liu Thesis Committee: Professor Ichiya Nakamura (Supervisor) Associate Professor Kazunori Sugiura (Co-supervisor) Professor Sam Furukawa (Member) Abstract of Master's Thesis of Academic Year 2015 A Rewards-Based Crowdfunding Platform for Chinese Doujin Fans and Doujin Creators Category: Design Summary Doujin is stated as a general Japanese term for a group of people who share an interest, activity, hobbies, or achievement. In the field of doujin, amateur self- published works are called doujin works, including but not limited to fan fiction, illustration, comic, music, and game. Doujin work is a part of a wider category of doujin. -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

Q1 2007 8 Table of the Punch Line Contents

Q1 2007 8 Table of The Punch Line Contents 4 On the Grand Master’s Stage 34 Persona Visits the Wii Line Strider–ARC AnIllustratedCampoutfortheWii 6 Goading ‘n Gouging 42 Christmas Morning at the Ghouls‘nGoblinsseries Leukemia Ward TokyoGameShow2006 12 That Spiky-Haired Lawyer is All Talk PhoenixWright:AceAttorney–NDS 50 A Retrospective Survival Guide to Tokyo Game Show 14 Shinji Mikami and the Lost Art of WithExtra-SpecialBlueDragon Game Design Preview ResidentEvil-PS1;P.N.03,Resident Evil4-NGC;GodHand-PS2 54 You’ve Won a Prize! Deplayability 18 Secrets and Save Points SecretofMana–SNES 56 Knee-Deep in Legend Doom–PC 22 Giving Up the Ghost MetroidII:ReturnofSamus–NGB 58 Killing Dad and Getting it Right ShadowHearts–PS2 25 I Came Wearing a Full Suit of Armour But I Left Wearing 60 The Sound of Horns and Motors Only My Pants Falloutseries Comic 64 The Punch Line 26 Militia II is Machinima RuleofRose-PS2 MilitiaII–AVI 68 Untold Tales of the Arcade 30 Mega Microcosms KillingDragonsHasNever Wariowareseries BeenSoMuchFun! 76 Why Game? Reason#7:WhyNot!? Table Of Contents 1 From the Editor’s Desk Staff Keep On Keeping On Asatrustedfriendsaidtome,“Aslong By Matthew Williamson asyoukeepwritingandcreating,that’s Editor In Chief: Staff Artists: Matthew“ShaperMC”Williamson Mariel“Kinuko”Cartwright allIcareabout.”Andthat’swhatI’lldo, [email protected] [email protected] It’sbeenalittlewhilesinceourlast andwhatI’llhelpotherstodoaswell. Associate Editor: Jonathan“Persona-Sama”Kim issuecameout;Ihopeyouenjoyedthe Butdon’tworryaboutThe Gamer’s Ancil“dessgeega”Anthropy [email protected] anticipation.Timeissomethingstrange, Quarter;wehavebigplans.Wewillbe [email protected] Benjamin“Lestrade”Rivers though.Hasitreallybeenovertwo shiftingfromastrictquarterlysched- Assistant Editor: [email protected] yearsnow?Itgoessofast. -

Lexis Practice Advisor Intellectual Property & Technology Determining

Lexis Practice Advisor® is a comprehensive practical guidance resource for attorneys who handle transactional matters, including “how to” information, model forms and on point cases, codes and legal analysis. The Intellectual Property & Technology offering contains access to a unique collection of expertly authored content, continuously updated to help you stay up to speed on leading practice trends. The following is a practical guidance excerpt from the topic Copyright Ownership & Registration. Lexis Practice Advisor Intellectual Property & Technology Determining Copyright Ownership by Jeremy S. Goldman, Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz PC Jeremy S. Goldman is counsel in the Litigation Group of Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz PC, where he focuses on intellectual property, entertainment and privacy law for clients in the media, entertainment, advertising and technology spaces. Overview Copyright protection is given to authors of original and expressive works , including literary, musical, dramatic, sculptural, and certain other categories of works, which are fixed in a tangible medium. Although the author of a copyrighted work is generally also the creator of the work, there are exceptions to this, such as works made for hire and works jointly authored by more than one person. A copyright in a derivative work protects only the new and original elements added to preexisting work; the author of the derivative work has no ownership interest in the preexisting work. The ownership of a copyright may be transferred or assigned, in whole or in part. That is, each of the exclusive rights afforded a copyright owner under the Copyright Act may be owned and transferred separately. To the extent there are conflicting transfers, the prior transferee will have priority over any subsequent transferee so long as the transfer is recorded within one month of execution (for transfers made in the United States), or at any time prior to recordation of the transfer to a subsequent transferee. -

An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer

Cybaris® Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 2015 An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Schreyer, Amanda (2015) "An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests," Cybaris®: Vol. 6: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cybaris® by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Schreyer: An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balanci Published by Mitchell Hamline Open Access, 2015 1 Cybaris®, Vol. 6, Iss. 1 [2015], Art. 3 AN OVERVIEW OF LEGAL PROTECTION FOR FICTIONAL CHARACTERS: BALANCING PUBLIC AND PRIVATE INTERESTS † AMANDA SCHREYER I. Fictional Characters and the Law .............................................. 52! II. Legal Basis for Protecting Characters ...................................... 53! III. Copyright Protection of Characters ........................................ 57! A. Literary Characters Versus Visual Characters ............... 60! B. Component Parts of Characters Can Be Separately Copyrightable ................................................................ -

Computer Software Derivative Works: the Calm Before the Storm

COMPUTER SOFTWARE DERIVATIVE WORKS: THE CALM BEFORE THE STORM Natalie Heineman* Cite as 8 J. HIGH TECH. L. 235 (2008) I. Introduction Every generation believes they live in the most exciting times of continued social and technological advancement. Since the advent of computers and the internet, however, the present is a time in which progress seems unrivaled. While the law races to catch up with technology, the area of law requiring the fastest runners may be that of computer software derivative works under current copyright law. An author’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works is particularly challenged in the software environment where innovation often involves references to and incorporation of other preexisting works. Without definitive cases on point or specifically tailored legislation to guide the analysis, however, the scope of this note is simply to help define the issues presented, thereby drawing attention to what looks to be the calm before the impending storm. This note considers the challenge posed by computer software derivative works. The note first discusses the definition of derivative works under the current Copyright Act, and analyzes how the courts have interpreted derivative works in analogous contexts. Because defining a derivative work necessarily considers whether it has infringed the underlying work, the note then discusses how the courts make infringement analyses. The infringement analysis focuses primarily on the abstraction-filtration method as it has developed in computer software cases. Finally, the note considers trends in cases and legislation that suggest an increasingly broad interpretation of derivative rights. This section emphasizes the Open Source movement which will no doubt have a significant impact on the future of computer software derivative works. -

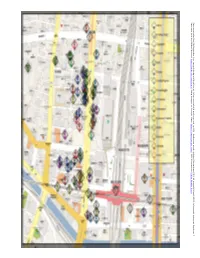

Map a Ssem B Le D an D Ma Rk Ed by Zim. Softw a Re Used

Data compiled by ZiM (parabellum.rounds(at)gmail(dot)com). Map assembled and marked by ZiM. Software used: Adobe Photoshop CS3, Microsoft Word 2007, Microsoft Internet Explorer 7. Data and text by Akiba Channel: http://akiba‐ch.com/map/. Map images by Google Maps: http://maps.google.com/. PDF Conversion White Rabbit Press Retro Visual/Audio 1 Super Potato 3F Nintendo, Sega; 4F Sony; 5F Retro game arcade. 1 Sofmap Music CD Store 1F: New CDs, JPOP CDs; 2F: Anime, Game CDs; 3F: Best retro game store in Akiba, on upper floors. New, used CDs; 4F: Event 2 Retro Game Store #7 New store, next to Sofmap Store. Retro games. PC Games Trading Cards 1 Medio! X PC games. Rarities displayed. 1 Yellow Submarine Well stocked with anime and trading cards. 2 Sofmap PC Game/Anime B1: Used PC games, game OST CD; 1F: New PC Trading Card Store Store Games, Music CDs, game magazines; 2F: New Radio Kaikan 7F Anime DVD, Used Anime OST; 3F: Figures 2 Hobby Station Alternate figures and trading card store. 3 Getchu‐ya 3F store. Few games in stock. Rental showcase on 3 Amenity Dream Recommended trading card shop in Akiba, on 6F. 2F, used game/anime/CD store on 1F. Biggest stock of single cards, playing space. Recreation 4 Yellow Submarine Magic‐ Vast trading card booster packs stock. Expensive. 1 Karaoke Pasera Themed after popular anime and shows. ers 2 GeraGera Manga Cafe Few places to access net. Pricey. Transport 3 AION Pachinko place. Anime, game themed machines. 1 Akihabara JR Station 4 Island Pachinko place on bottom floor. -

GAMING GLOBAL a Report for British Council Nick Webber and Paul Long with Assistance from Oliver Williams and Jerome Turner

GAMING GLOBAL A report for British Council Nick Webber and Paul Long with assistance from Oliver Williams and Jerome Turner I Executive Summary The Gaming Global report explores the games environment in: five EU countries, • Finland • France • Germany • Poland • UK three non-EU countries, • Brazil • Russia • Republic of Korea and one non-European region. • East Asia It takes a culturally-focused approach, offers examples of innovative work, and makes the case for British Council’s engagement with the games sector, both as an entertainment and leisure sector, and as a culturally-productive contributor to the arts. What does the international landscape for gaming look like? In economic terms, the international video games market was worth approximately $75.5 billion in 2013, and will grow to almost $103 billion by 2017. In the UK video games are the most valuable purchased entertainment market, outstripping cinema, recorded music and DVDs. UK developers make a significant contribution in many formats and spaces, as do developers across the EU. Beyond the EU, there are established industries in a number of countries (notably Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand) who access international markets, with new entrants such as China and Brazil moving in that direction. Video games are almost always categorised as part of the creative economy, situating them within the scope of investment and promotion by a number of governments. Many countries draw on UK models of policy, although different countries take games either more or less seriously in terms of their cultural significance. The games industry tends to receive innovation funding, with money available through focused programmes. -

Retro Gamer Speed Pretty Quickly, Shifting to a Contents Will Remain the Same

Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RETRO12 Intro/Hello:RETRO12 Intro/Hello 14/9/06 15:56 Page 3 hel <EDITORIAL> >10 PRINT "hello" Editor = >20 GOTO 10 Martyn Carroll >RUN ([email protected]) Staff Writer = Shaun Bebbington ([email protected]) Art Editor = Mat Mabe Additonal Design = Mr Beast + Wendy Morgan Sub Editors = Rachel White + Katie Hallam Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Aaron Birch Richard Burton + Keith Campbell David Crookes + Jonti Davies Paul Drury + Andrew Fisher Andy Krouwel + Peter Latimer Craig Vaughan + Gareth Warde Thomas Wilde <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Debbie Whitham Group Sales & Marketing Manager = Tony Allen hello Advertising Sales = elcome Retro Gamer speed pretty quickly, shifting to a contents will remain the same. Linda Henry readers old and new to monthly frequency, and we’ve We’ve taken onboard an enormous Accounts Manager = issue 12. By all even been able to publish a ‘best amount of reader feedback, so the Karen Battrick W Circulation Manager = accounts, we should be of’ in the shape of our Retro changes are a direct response to Steve Hobbs celebrating the magazine’s first Gamer Anthology. My feet have what you’ve told us. And of Marketing Manager = birthday, but seeing as the yet to touch the ground. course, we want to hear your Iain "Chopper" Anderson Editorial Director = frequency of the first two or three Remember when magazines thoughts on the changes, so we Wayne Williams issues was a little erratic, it’s a used to be published in 12-issue can continually make the Publisher = little over a year old now. -

MAD SCIENCE! Ab Science Inc

MAD SCIENCE! aB Science Inc. PROGRAM GUIDEBOOK “Leaders in Industry” WARNING! MAY CONTAIN: Vv Highly Evil Violations of Volatile Sentient :D Space-Time Materials Robots Laws FOOT table of contents 3 Letters from the Co-Chairs 4 Guests of Honor 10 Events 15 Video Programming 18 Panels & Workshops 28 Artists’ Alley 32 Dealers Room 34 Room Directory 35 Maps 41 Where to Eat 48 Tipping Guide 49 Getting Around 50 Rules 55 Volunteering 58 Staff 61 Sponsors 62 Fun & Games 64 Autographs APRIL 2-4, 2O1O 1 IN MEMORY OF TODD MACDONALD “We will miss and love you always, Todd. Thank you so much for being a friend, a staffer, and for the support you’ve always offered, selflessly and without hesitation.” —Andrea Finnin LETTERS FROM THE CO-CHAIRS Anime Boston has given me unique growth Hello everyone, welcome to Anime Boston! opportunities, and I have become closer to people I already knew outside of the convention. I hope you all had a good year, though I know most of us had a pretty bad year, what with the economy, increasing healthcare This strengthening of bonds brought me back each year, but 2010 costs and natural disasters (donate to Haiti!). At Anime Boston, is different. In the summer of 2009, Anime Boston lost a dear I hope we can provide you with at least a little enjoyment. friend and veteran staffer when Todd MacDonald passed away. We’ve been working long and hard to get composer Nobuo When Todd joined staff in 2002, it was only because I begged. Uematsu, most famous for scoring most of the music for the Few on staff imagined that our three-day convention was going Final Fantasy games as well as other Square Enix games such to be such an amazing success.