The History of PI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

Mathematicians

MATHEMATICIANS [MATHEMATICIANS] Authors: Oliver Knill: 2000 Literature: Started from a list of names with birthdates grabbed from mactutor in 2000. Abbe [Abbe] Abbe Ernst (1840-1909) Abel [Abel] Abel Niels Henrik (1802-1829) Norwegian mathematician. Significant contributions to algebra and anal- ysis, in particular the study of groups and series. Famous for proving the insolubility of the quintic equation at the age of 19. AbrahamMax [AbrahamMax] Abraham Max (1875-1922) Ackermann [Ackermann] Ackermann Wilhelm (1896-1962) AdamsFrank [AdamsFrank] Adams J Frank (1930-1989) Adams [Adams] Adams John Couch (1819-1892) Adelard [Adelard] Adelard of Bath (1075-1160) Adler [Adler] Adler August (1863-1923) Adrain [Adrain] Adrain Robert (1775-1843) Aepinus [Aepinus] Aepinus Franz (1724-1802) Agnesi [Agnesi] Agnesi Maria (1718-1799) Ahlfors [Ahlfors] Ahlfors Lars (1907-1996) Finnish mathematician working in complex analysis, was also professor at Harvard from 1946, retiring in 1977. Ahlfors won both the Fields medal in 1936 and the Wolf prize in 1981. Ahmes [Ahmes] Ahmes (1680BC-1620BC) Aida [Aida] Aida Yasuaki (1747-1817) Aiken [Aiken] Aiken Howard (1900-1973) Airy [Airy] Airy George (1801-1892) Aitken [Aitken] Aitken Alec (1895-1967) Ajima [Ajima] Ajima Naonobu (1732-1798) Akhiezer [Akhiezer] Akhiezer Naum Ilich (1901-1980) Albanese [Albanese] Albanese Giacomo (1890-1948) Albert [Albert] Albert of Saxony (1316-1390) AlbertAbraham [AlbertAbraham] Albert A Adrian (1905-1972) Alberti [Alberti] Alberti Leone (1404-1472) Albertus [Albertus] Albertus Magnus -

Plato As "Architectof Science"

Plato as "Architectof Science" LEONID ZHMUD ABSTRACT The figureof the cordialhost of the Academy,who invitedthe mostgifted math- ematiciansand cultivatedpure research, whose keen intellectwas able if not to solve the particularproblem then at least to show the methodfor its solution: this figureis quite familiarto studentsof Greekscience. But was the Academy as such a centerof scientificresearch, and did Plato really set for mathemati- cians and astronomersthe problemsthey shouldstudy and methodsthey should use? Oursources tell aboutPlato's friendship or at leastacquaintance with many brilliantmathematicians of his day (Theodorus,Archytas, Theaetetus), but they were neverhis pupils,rather vice versa- he learnedmuch from them and actively used this knowledgein developinghis philosophy.There is no reliableevidence that Eudoxus,Menaechmus, Dinostratus, Theudius, and others, whom many scholarsunite into the groupof so-called"Academic mathematicians," ever were his pupilsor close associates.Our analysis of therelevant passages (Eratosthenes' Platonicus, Sosigenes ap. Simplicius, Proclus' Catalogue of geometers, and Philodemus'History of the Academy,etc.) shows thatthe very tendencyof por- trayingPlato as the architectof sciencegoes back to the earlyAcademy and is bornout of interpretationsof his dialogues. I Plato's relationship to the exact sciences used to be one of the traditional problems in the history of ancient Greek science and philosophy.' From the nineteenth century on it was examined in various aspects, the most significant of which were the historical, philosophical and methodological. In the last century and at the beginning of this century attention was paid peredominantly, although not exclusively, to the first of these aspects, especially to the questions how great Plato's contribution to specific math- ematical research really was, and how reliable our sources are in ascrib- ing to him particular scientific discoveries. -

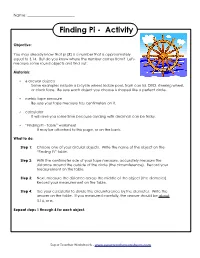

Finding Pi Project

Name: ________________________ Finding Pi - Activity Objective: You may already know that pi (π) is a number that is approximately equal to 3.14. But do you know where the number comes from? Let's measure some round objects and find out. Materials: • 6 circular objects Some examples include a bicycle wheel, kiddie pool, trash can lid, DVD, steering wheel, or clock face. Be sure each object you choose is shaped like a perfect circle. • metric tape measure Be sure your tape measure has centimeters on it. • calculator It will save you some time because dividing with decimals can be tricky. • “Finding Pi - Table” worksheet It may be attached to this page, or on the back. What to do: Step 1: Choose one of your circular objects. Write the name of the object on the “Finding Pi” table. Step 2: With the centimeter side of your tape measure, accurately measure the distance around the outside of the circle (the circumference). Record your measurement on the table. Step 3: Next, measure the distance across the middle of the object (the diameter). Record your measurement on the table. Step 4: Use your calculator to divide the circumference by the diameter. Write the answer on the table. If you measured carefully, the answer should be about 3.14, or π. Repeat steps 1 through 4 for each object. Super Teacher Worksheets - www.superteacherworksheets.com Name: ________________________ “Finding Pi” Table Measure circular objects and complete the table below. If your measurements are accurate, you should be able to calculate the number pi (3.14). Is your answer name of circumference diameter circumference ÷ approximately circular object measurement (cm) measurement (cm) diameter equal to π? 1. -

Squaring the Circle in Elliptic Geometry

Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal Volume 18 Issue 2 Article 1 Squaring the Circle in Elliptic Geometry Noah Davis Aquinas College Kyle Jansens Aquinas College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rhumj Recommended Citation Davis, Noah and Jansens, Kyle (2017) "Squaring the Circle in Elliptic Geometry," Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal: Vol. 18 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rhumj/vol18/iss2/1 Rose- Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal squaring the circle in elliptic geometry Noah Davis a Kyle Jansensb Volume 18, No. 2, Fall 2017 Sponsored by Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Department of Mathematics Terre Haute, IN 47803 a [email protected] Aquinas College b scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rhumj Aquinas College Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal Volume 18, No. 2, Fall 2017 squaring the circle in elliptic geometry Noah Davis Kyle Jansens Abstract. Constructing a regular quadrilateral (square) and circle of equal area was proved impossible in Euclidean geometry in 1882. Hyperbolic geometry, however, allows this construction. In this article, we complete the story, providing and proving a construction for squaring the circle in elliptic geometry. We also find the same additional requirements as the hyperbolic case: only certain angle sizes work for the squares and only certain radius sizes work for the circles; and the square and circle constructions do not rely on each other. Acknowledgements: We thank the Mohler-Thompson Program for supporting our work in summer 2014. Page 2 RHIT Undergrad. Math. J., Vol. 18, No. 2 1 Introduction In the Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Math Journal, 15 1 2014, Noah Davis demonstrated the construction of a hyperbolic circle and hyperbolic square in the Poincar´edisk [1]. -

Evaluating Fourier Transforms with MATLAB

ECE 460 – Introduction to Communication Systems MATLAB Tutorial #2 Evaluating Fourier Transforms with MATLAB In class we study the analytic approach for determining the Fourier transform of a continuous time signal. In this tutorial numerical methods are used for finding the Fourier transform of continuous time signals with MATLAB are presented. Using MATLAB to Plot the Fourier Transform of a Time Function The aperiodic pulse shown below: x(t) 1 t -2 2 has a Fourier transform: X ( jf ) = 4sinc(4π f ) This can be found using the Table of Fourier Transforms. We can use MATLAB to plot this transform. MATLAB has a built-in sinc function. However, the definition of the MATLAB sinc function is slightly different than the one used in class and on the Fourier transform table. In MATLAB: sin(π x) sinc(x) = π x Thus, in MATLAB we write the transform, X, using sinc(4f), since the π factor is built in to the function. The following MATLAB commands will plot this Fourier Transform: >> f=-5:.01:5; >> X=4*sinc(4*f); >> plot(f,X) In this case, the Fourier transform is a purely real function. Thus, we can plot it as shown above. In general, Fourier transforms are complex functions and we need to plot the amplitude and phase spectrum separately. This can be done using the following commands: >> plot(f,abs(X)) >> plot(f,angle(X)) Note that the angle is either zero or π. This reflects the positive and negative values of the transform function. Performing the Fourier Integral Numerically For the pulse presented above, the Fourier transform can be found easily using the table. -

Unit 3, Lesson 1: How Well Can You Measure?

GRADE 7 MATHEMATICS NAME DATE PERIOD Unit 3, Lesson 1: How Well Can You Measure? 1. Estimate the side length of a square that has a 9 cm long diagonal. 2. Select all quantities that are proportional to the diagonal length of a square. A. Area of a square B. Perimeter of a square C. Side length of a square 3. Diego made a graph of two quantities that he measured and said, “The points all lie on a line except one, which is a little bit above the line. This means that the quantities can’t be proportional.” Do you agree with Diego? Explain. 4. The graph shows that while it was being filled, the amount of water in gallons in a swimming pool was approximately proportional to the time that has passed in minutes. a. About how much water was in the pool after 25 minutes? b. Approximately when were there 500 gallons of water in the pool? c. Estimate the constant of proportionality for the number of gallons of water per minute going into the pool. Unit 3: Measuring Circles Lesson 1: How Well Can You Measure? 1 GRADE 7 MATHEMATICS NAME DATE PERIOD Unit 3: Measuring Circles Lesson 1: How Well Can You Measure? 2 GRADE 7 MATHEMATICS NAME DATE PERIOD Unit 3, Lesson 2: Exploring Circles 1. Use a geometric tool to draw a circle. Draw and measure a radius and a diameter of the circle. 2. Here is a circle with center and some line segments and curves joining points on the circle. Identify examples of the following. -

Archimedes and Pi

Archimedes and Pi Burton Rosenberg September 7, 2003 Introduction Proposition 3 of Archimedes’ Measurement of a Circle states that π is less than 22/7 and greater than 223/71. The approximation πa ≈ 22/7 is referred to as Archimedes Approximation and is very good. It has been reported that a 2000 B.C. Babylonian approximation is πb ≈ 25/8. We will compare these two approximations. The author, in the spirit of idiot’s advocate, will venture his own approximation of πc ≈ 19/6. The Babylonian approximation is good to one part in 189, the author’s, one part in 125, and Archimedes an astonishing one part in 2484. Archimedes’ approach is to circumscribe and inscribe regular n-gons around a unit circle. He begins with a hexagon and repeatedly subdivides the side to get 12, 24, 48 and 96-gons. The semi-circumference of these polygons converge on π from above and below. In modern terms, Archimede’s derives and uses the cotangent half-angle formula, cot x/2 = cot x + csc x. In application, the cosecant will be calculated from the cotangent according to the (modern) iden- tity, csc2 x = 1 + cot2 x Greek mathematics dealt with ratio’s more than with numbers. Among the often used ratios are the proportions among the sides of a triangle. Although Greek mathematics is said to not know trigonometric functions, we shall see how conversant it was with these ratios and the formal manipulation of ratios, resulting in a theory essentially equivalent to that of trigonometry. For the circumscribed polygon We use the notation of the Dijksterhuis translation of Archimedes. -

Archimedes Palimpsest a Brief History of the Palimpsest Tracing the Manuscript from Its Creation Until Its Reappearance Foundations...The Life of Archimedes

Archimedes Palimpsest A Brief History of the Palimpsest Tracing the manuscript from its creation until its reappearance Foundations...The Life of Archimedes Birth: About 287 BC in Syracuse, Sicily (At the time it was still an Independent Greek city-state) Death: 212 or 211 BC in Syracuse. His age is estimated to be between 75-76 at the time of death. Cause: Archimedes may have been killed by a Roman soldier who was unaware of who Archimedes was. This theory however, has no proof. However, the dates coincide with the time Syracuse was sacked by the Roman army. The Works of Archimedes Archimedes' Writings: • Balancing Planes • Quadrature of the Parabola • Sphere and Cylinder • Spiral Lines • Conoids and Spheroids • On Floating Bodies • Measurement of a Circle • The Sandreckoner • The Method of Mechanical Problems • The Stomachion The ABCs of Archimedes' work Archimedes' work is separated into three Codeces: Codex A: Codex B: • Balancing Planes • Balancing Planes • Quadrature of the Parabola • Quadrature of the Parabola • Sphere and Cylinder • On Floating Bodies • Spiral Lines Codex C: • Conoids and Spheroids • The Method of Mechanical • Measurement of a Circle Problems • The Sand-reckoner • Spiral Lines • The Stomachion • On Floating Bodies • Measurement of a Circle • Balancing Planes • Sphere and Cylinder The Reappearance of the Palimpsest Date: On Thursday, October 29, 1998 Location: Christie's Acution House, NY Selling price: $2.2 Million Research on Palimpsest was done by Walter's Art Museum in Baltimore, MD The Main Researchers Include: William Noel Mike Toth Reviel Netz Keith Knox Uwe Bergmann Codex A, B no more Codex A and B no longer exist. -

MATLAB Examples Mathematics

MATLAB Examples Mathematics Hans-Petter Halvorsen, M.Sc. Mathematics with MATLAB • MATLAB is a powerful tool for mathematical calculations. • Type “help elfun” (elementary math functions) in the Command window for more information about basic mathematical functions. Mathematics Topics • Basic Math Functions and Expressions � = 3�% + ) �% + �% + �+,(.) • Statistics – mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, maximum and variance • Trigonometric Functions sin() , cos() , tan() • Complex Numbers � = � + �� • Polynomials = =>< � � = �<� + �%� + ⋯ + �=� + �=@< Basic Math Functions Create a function that calculates the following mathematical expression: � = 3�% + ) �% + �% + �+,(.) We will test with different values for � and � We create the function: function z=calcexpression(x,y) z=3*x^2 + sqrt(x^2+y^2)+exp(log(x)); Testing the function gives: >> x=2; >> y=2; >> calcexpression(x,y) ans = 16.8284 Statistics Functions • MATLAB has lots of built-in functions for Statistics • Create a vector with random numbers between 0 and 100. Find the following statistics: mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, maximum and the variance. >> x=rand(100,1)*100; >> mean(x) >> median(x) >> std(x) >> mean(x) >> min(x) >> max(x) >> var(x) Trigonometric functions sin(�) cos(�) tan(�) Trigonometric functions It is quite easy to convert from radians to degrees or from degrees to radians. We have that: 2� ������� = 360 ������� This gives: 180 � ������� = �[�������] M � � �[�������] = �[�������] M 180 → Create two functions that convert from radians to degrees (r2d(x)) and from degrees to radians (d2r(x)) respectively. Test the functions to make sure that they work as expected. The functions are as follows: function d = r2d(r) d=r*180/pi; function r = d2r(d) r=d*pi/180; Testing the functions: >> r2d(2*pi) ans = 360 >> d2r(180) ans = 3.1416 Trigonometric functions Given right triangle: • Create a function that finds the angle A (in degrees) based on input arguments (a,c), (b,c) and (a,b) respectively. -

Some Curves and the Lengths of Their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs. 2021. hal-03236909 HAL Id: hal-03236909 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03236909 Preprint submitted on 26 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna Department of Applied Science and Technology Politecnico di Torino Here we consider some problems from the Finkel's solution book, concerning the length of curves. The curves are Cissoid of Diocles, Conchoid of Nicomedes, Lemniscate of Bernoulli, Versiera of Agnesi, Limaçon, Quadratrix, Spiral of Archimedes, Reciprocal or Hyperbolic spiral, the Lituus, Logarithmic spiral, Curve of Pursuit, a curve on the cone and the Loxodrome. The Versiera will be discussed in detail and the link of its name to the Versine function. Torino, 2 May 2021, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4732881 Here we consider some of the problems propose in the Finkel's solution book, having the full title: A mathematical solution book containing systematic solutions of many of the most difficult problems, Taken from the Leading Authors on Arithmetic and Algebra, Many Problems and Solutions from Geometry, Trigonometry and Calculus, Many Problems and Solutions from the Leading Mathematical Journals of the United States, and Many Original Problems and Solutions. -

On Archimedes' Measurement of a Circle, Proposition 3

On Archimedes’ Measurement of a circle, Proposition 3 Mark Reeder February 2 1 10 The ratio of the circumference of any circle to its diameter is less than 3 7 but greater than 3 71 . Having related the area of a circle to its perimeter in Prop. 1, Archimedes next approximates the circle perimeter with circumscribed and inscribed regular polygons and then finds good rational estimates for these polygon perimeters, thereby approximating the ratio of circumference to diameter. The main geometric step is to see how the polygon perimeter changes when the number of sides is doubled. We will consider the circumscribed case. Let AC be a side of a regular circumscribing polygon, and let AD be a side of a regular polygon with the number of sides doubled. C D θ O A θ B To make Archimedes’ computation easier to follow, let x = AC, y = AD, r = OA, c = OC, d = OD. We want to express the new ratio y/r in terms of the old ratio x/r. But these numbers will be very small after a few subdivisions, so they will be difficult to estimate. Instead, we will express r/y in terms of r/x. These are big numbers, which can be estimated by integers. 1 From Euclid VI.3, an angle bisector divides the opposite side in the same ratio as the other two sides of a triangle. Hence CD : DA = OC : OA. In our notation, this means x − y c x c + r r r c = , or = , or = + . y r y r y x x From Euclid I.47, we have r c r2 = 1 + , x x2 so that r r r r2 = + 1 + (1) y x x2 Thus, the new ratio r/y is expressed in terms of the old ratio r/x, as desired.