Information Module Basilosaurus Isis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

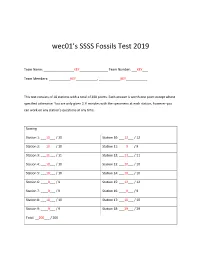

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and Associated Biota from Georgia Author(S): Richard C

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and Associated Biota from Georgia Author(s): Richard C. Hulbert, Jr., Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry and David P. Aleshire Source: Journal of Paleontology , Sep., 1998, Vol. 72, No. 5 (Sep., 1998), pp. 907-927 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1306667 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1306667?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Paleontology This content downloaded from 131.204.154.192 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 18:43:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms J. Paleont., 72(5), 1998, pp. 907-927 Copyright ? 1998, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/98/0072-0907$03.00 A NEW MIDDLE EOCENE PROTOCETID WHALE (MAMMALIA: CETACEA: ARCHAEOCETI) AND ASSOCIATED BIOTA FROM GEORGIA RICHARD C. HULBERT, JR.,1 RICHARD M. PETKEWICH,"4 GALE A. -

Functional Morphology of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus (Mammalia, Cetacea) and the Evolution of Aquatic Locomotion in Early Archaeocetes

Functional Morphology of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus (Mammalia, Cetacea) and the Evolution of Aquatic Locomotion in Early Archaeocetes by Ryan Matthew Bebej A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Philip D. Gingerich, Co-Chair Professor Philip Myers, Co-Chair Professor Daniel C. Fisher Professor Paul W. Webb © Ryan Matthew Bebej 2011 To my wonderful wife Melissa, for her infinite love and support ii Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank each of my committee members. I will be forever grateful to my primary mentor, Philip D. Gingerich, for providing me the opportunity of a lifetime, studying the very organisms that sparked my interest in evolution and paleontology in the first place. His encouragement, patience, instruction, and advice have been instrumental in my development as a scholar, and his dedication to his craft has instilled in me the importance of doing careful and solid research. I am extremely grateful to Philip Myers, who graciously consented to be my co-advisor and co-chair early in my career and guided me through some of the most stressful aspects of life as a Ph.D. student (e.g., preliminary examinations). I also thank Paul W. Webb, for his novel thoughts about living in and moving through water, and Daniel C. Fisher, for his insights into functional morphology, 3D modeling, and mammalian paleobiology. My research was almost entirely predicated on cetacean fossils collected through a collaboration of the University of Michigan and the Geological Survey of Pakistan before my arrival in Ann Arbor. -

Currently Zygorhiza Kochii; Mammalia, Cetacea): Proposed Replacement of the Holotype by a Neotype

Case 3611Basilosaurus kochii Reichenbach, 1847 (currently Zygorhiza kochii; Mammalia, Cetacea): proposed replacement of the holotype by a neotype Author: Uhen, Mark D. Source: The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 70(2) : 103-107 Published By: International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature URL: https://doi.org/10.21805/bzn.v70i2.a14 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/The-Bulletin-of-Zoological-Nomenclature on 08 Apr 2021 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Auburn University Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 70(2) June 2013 103 Case 3611 Basilosaurus kochii Reichenbach, 1847 (currently Zygorhiza kochii; Mammalia, Cetacea): proposed replacement of the holotype by a neotype Mark D. Uhen Department of Atmospheric, Oceanic, and Earth Sciences, George Mason University, MS 5F2, Fairfax, VA 22030, U.S.A. (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract. -

Transition of Eocene Whales from Land to Sea: Evidence from Bone Microstructure

RESEARCH ARTICLE Transition of Eocene Whales from Land to Sea: Evidence from Bone Microstructure Alexandra Houssaye1,2*, Paul Tafforeau3, Christian de Muizon4, Philip D. Gingerich5 1 UMR 7179 CNRS/Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Département Ecologie et Gestion de la Biodiversité, Paris, France, 2 Steinmann Institut für Geologie, Paläontologie und Mineralogie, Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 3 European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France, 4 Sorbonne Universités, CR2P—CNRS, MNHN, UPMC-Paris 6, Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France, 5 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States of America a11111 * [email protected] Abstract Cetacea are secondarily aquatic amniotes that underwent their land-to-sea transition during OPEN ACCESS the Eocene. Primitive forms, called archaeocetes, include five families with distinct degrees Citation: Houssaye A, Tafforeau P, de Muizon C, of adaptation to an aquatic life, swimming mode and abilities that remain difficult to estimate. Gingerich PD (2015) Transition of Eocene Whales The lifestyle of early cetaceans is investigated by analysis of microanatomical features in from Land to Sea: Evidence from Bone postcranial elements of archaeocetes. We document the internal structure of long bones, Microstructure. PLoS ONE 10(2): e0118409. ribs and vertebrae in fifteen specimens belonging to the three more derived archaeocete doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118409 families — Remingtonocetidae, Protocetidae, and Basilosauridae — using microtomogra- Academic Editor: Brian Lee Beatty, New York phy and virtual thin-sectioning. This enables us to discuss the osseous specializations ob- Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine, UNITED STATES served in these taxa and to comment on their possible swimming behavior. -

How Many Species of Mammals Are There?

Journal of Mammalogy, 99(1):1–14, 2018 DOI:10.1093/jmammal/gyx147 INVITED PAPER How many species of mammals are there? CONNOR J. BURGIN,1 JOCELYN P. COLELLA,1 PHILIP L. KAHN, AND NATHAN S. UPHAM* Department of Biological Sciences, Boise State University, 1910 University Drive, Boise, ID 83725, USA (CJB) Department of Biology and Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, MSC03-2020, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA (JPC) Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA (PLK) Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA (NSU) Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605, USA (NSU) 1Co-first authors. * Correspondent: [email protected] Accurate taxonomy is central to the study of biological diversity, as it provides the needed evolutionary framework for taxon sampling and interpreting results. While the number of recognized species in the class Mammalia has increased through time, tabulation of those increases has relied on the sporadic release of revisionary compendia like the Mammal Species of the World (MSW) series. Here, we present the Mammal Diversity Database (MDD), a digital, publically accessible, and updateable list of all mammalian species, now available online: https://mammaldiversity.org. The MDD will continue to be updated as manuscripts describing new species and higher taxonomic changes are released. Starting from the baseline of the 3rd edition of MSW (MSW3), we performed a review of taxonomic changes published since 2004 and digitally linked species names to their original descriptions and subsequent revisionary articles in an interactive, hierarchical database. We found 6,495 species of currently recognized mammals (96 recently extinct, 6,399 extant), compared to 5,416 in MSW3 (75 extinct, 5,341 extant)—an increase of 1,079 species in about 13 years, including 11 species newly described as having gone extinct in the last 500 years. -

The Biology of Marine Mammals

Romero, A. 2009. The Biology of Marine Mammals. The Biology of Marine Mammals Aldemaro Romero, Ph.D. Arkansas State University Jonesboro, AR 2009 2 INTRODUCTION Dear students, 3 Chapter 1 Introduction to Marine Mammals 1.1. Overture Humans have always been fascinated with marine mammals. These creatures have been the basis of mythical tales since Antiquity. For centuries naturalists classified them as fish. Today they are symbols of the environmental movement as well as the source of heated controversies: whether we are dealing with the clubbing pub seals in the Arctic or whaling by industrialized nations, marine mammals continue to be a hot issue in science, politics, economics, and ethics. But if we want to better understand these issues, we need to learn more about marine mammal biology. The problem is that, despite increased research efforts, only in the last two decades we have made significant progress in learning about these creatures. And yet, that knowledge is largely limited to a handful of species because they are either relatively easy to observe in nature or because they can be studied in captivity. Still, because of television documentaries, ‘coffee-table’ books, displays in many aquaria around the world, and a growing whale and dolphin watching industry, people believe that they have a certain familiarity with many species of marine mammals (for more on the relationship between humans and marine mammals such as whales, see Ellis 1991, Forestell 2002). As late as 2002, a new species of beaked whale was being reported (Delbout et al. 2002), in 2003 a new species of baleen whale was described (Wada et al. -

Cetacea: Archaeoceti)

THE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES miSSISSippi• • • • geology Bureau of Geology Volume 7, Number 2 2525 North West Street December 1986 • Jackson, Mississippi 39216 FEEDING IN THE ARCHAEOCETE WHALE ZYGORHIZA KOCH/I {CETACEA: ARCHAEOCETI) Kenneth Carpenter 1805 Marine St. # C Boulder, Colorado 80302 David White 729 Chickasaw Drive Jackson, Mississippi 39206 ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION In order to test the various feeding hypotheses Archaeocete whales were the dominant predatory presented for the archaeocete whale, Zygorhiza marine mammals of the Eocene (Barnes, Damning, kochii, the masticatory musculature was restored. and Ray, 1985). Skeletal remains are distributed This restoration indicates that the important muscle globally, indicating just how successful these groups in descending order were Temporatis Group animals were. Their fossil remains are especially - Masseter Group - Pterygofdeus Group. This abundant in upper Eocene sediments and have musculature system is typical of carnivores. Tooth provided a great deal of information about their wear, in conjunction with the restored musculature, systematics, anatomy, and functional morphology suggests Zygorhiza primarily fed on fish, and (e.g. Stromer, 1903, 1908; Kellogg, 1928, 1936; possibly on squids as well. Breathnach, 1955; Edinger, 1955; Fleisher, 1976). Figure 1. Skull of Lophodon carcinophagus, AMNH 2194. The diet of archaeocete whales is frequently Yazoo County, Mississippi. The discovery of this assumed to be fish (e.g. Barnes and Mitchell, 1978), specimen is presented in Dockery (1974), Frazier although no detailed morphological evidence has (1980), and Carpenter and Dockery (1985). The local ever been presented in support of this hypothesis. geology is also presented in Dockery (1974), and a Kellogg (1928) suggested that the long rostrum was photographic record of the mounting of the skeleton used as forceps to catch prey. -

A Brief History of Whale Evolution: As Supported by The

A Brief History of Whale Evolution As Supported By the Fossil Record BIOB 272 – Genetics and Evolution Presented by Mindy Flanders Presented for Rick Henry December 8, 2017 Cetaceans—whales, dolphins, and porpoises—are so different from other animals that, until recently, scientists were unable to identify their closest relatives. As any elementary student knows, a whale is not a fish. That means that despite the similarities in where they live and how they look, whales are not at all like salmon or even sharks. Carolus Linnaeus, known for classifying plants and animals, noted in the 1750s that “whales breathe air through lungs not gills; are warm blooded; and have many other anatomical differences that distinguish them from fish” (Prothero, 2015). Other characteristics cetaceans share with all other mammals are: they have hair (at some point in their life), they give birth to live young, and they nurse their young with milk. This implies that whales evolved from other mammals and, because ancestral mammals were land animals, that whales had land ancestors (Thewissen & Bajpai, 2001). But before they had land ancestors they had water ancestors. The ancestors of fish lived in water, too. Up until 375 million years ago (mya), everything other than plants and insects lived in water, but it was around that time that fish and land animals began to diverge. A series of fossils represent the fish-to-tetrapod transition that occurred during the Late Devonian Period 359-383 mya (Herron & Freeman, 2014). In search of a new food source, or to escape predators more than twice their size (Prothero, 2015), the first tetrapods pushed themselves out of the swamps and began to live on land (Switek, 2010). -

Sound Transmission in Archaic and Modern Whales: Anatomical Adaptations for Underwater Hearing

THE ANATOMICAL RECORD 290:716–733 (2007) Sound Transmission in Archaic and Modern Whales: Anatomical Adaptations for Underwater Hearing SIRPA NUMMELA,1,2* J.G.M. THEWISSEN,1 SUNIL BAJPAI,3 4 5 TASEER HUSSAIN, AND KISHOR KUMAR 1Department of Anatomy, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, Rootstown, Ohio 2Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 3Department of Earth Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, Uttaranchal, India 4Department of Anatomy, Howard University, College of Medicine, Washington, DC 5Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, Dehradun, Uttaranchal, India ABSTRACT The whale ear, initially designed for hearing in air, became adapted for hearing underwater in less than ten million years of evolution. This study describes the evolution of underwater hearing in cetaceans, focusing on changes in sound transmission mechanisms. Measurements were made on 60 fossils of whole or partial skulls, isolated tympanics, middle ear ossicles, and mandibles from all six archaeocete families. Fossil data were compared with data on two families of modern mysticete whales and nine families of modern odontocete cetaceans, as well as five families of non- cetacean mammals. Results show that the outer ear pinna and external auditory meatus were functionally replaced by the mandible and the man- dibular fat pad, which posteriorly contacts the tympanic plate, the lateral wall of the bulla. Changes in the ear include thickening of the tympanic bulla medially, isolation of the tympanoperiotic complex by means of air sinuses, functional replacement of the tympanic membrane by a bony plate, and changes in ossicle shapes and orientation. Pakicetids, the ear- liest archaeocetes, had a land mammal ear for hearing in air, and used bone conduction underwater, aided by the heavy tympanic bulla. -

Whales and Wolves the Evidence

WHALES AND WOLVES THE EVIDENCE (Marx, et. al., n.d.) Pakicetus (48-50 million years ago) Found in Pakistan (Marx, et. al., n.d.) Ambulocetus (47-48 million years ago) Found in ancient estuaries or bays (Marx, et. al., n.d.) Rodhocetus (39-47 million years ago) Found in Africa and North America (Marx, et. al., n.d.) Basilosaurus (35-37 million years ago) Found in ocean deposits (Marx, et. al., n.d.) Dorudon atrox (Found in 35-38 million year old ocean deposits) Retrieved from: http://www.rejectionofpascalswager.net/origin.html Whale Fin Retrieved from: http://www.rejectionofpascalswager.net/origin.html Retrieved from: http://www.boneclones.com/BC-044.htm Orca Whale Lower Jaw Bone (San Diego Natural History Museum, 2010) Dire Wolf Jaw Bone What does the evidence tell us? ! Whales are mammals, so they share many similarities with the wolf, and are more closely related than a whale and shark. ! The skeleton pictures show the fossil evidence that has been found. They show that whales descended from a land mammal. This land mammal likely shares a common ancestor with wolves. Here is a drawing of what the land animal to whale evolution probably looked like: (Marx, et. al., n.d.) ! Using the geologic information about where the skeletons were found, you can see how the descendants moved from land to estuaries (fresh and salt water mixed) to oceans. ! Using comparative anatomy, you can see the homologous structures of the whale fin and wolf leg. This suggests that they share a common ancestor. ! Using comparative anatomy, you can see the homologous structures of the whale jaw bone and the wolf jaw bone. -

Origin and Evolution of Large Brains in Toothed Whales

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 12-2004 Origin and Evolution of Large Brains in Toothed Whales Lori Marino Emory University Daniel W. McShea Duke University Mark D. Uhen Cranbrook Institute of Science Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_vsm Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Marino, L., McShea, D. W., & Uhen, M. D. (2004). Origin and evolution of large brains in toothed whales. The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology, 281(2), 1247-1255. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Origin and Evolution of Large Brains in Toothed Whales Lori Marino1, Daniel W. McShea2, and Mark D. Uhen3 1 Emory University 2 Duke University 3 Cranbrook Institute of Science KEYWORDS cetacean, encephalization, odontocetes ABSTRACT Toothed whales (order Cetacea: suborder Odontoceti) are highly encephalized, possessing brains that are significantly larger than expected for their body sizes. In particular, the odontocete superfamily Delphinoidea (dolphins, porpoises, belugas, and narwhals) comprises numerous species with encephalization levels second only to modern humans and greater than all other mammals. Odontocetes have also demonstrated behavioral faculties previously only ascribed to humans and, to some extent, other great apes. How did the large brains of odontocetes evolve? To begin to investigate this question, we quantified and averaged estimates of brain and body size for 36 fossil cetacean species using computed tomography and analyzed these data along with those for modern odontocetes.