The Mahabharata Is in the Soul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana The Bh āgavata Pur āṇa (Devanagari : भागवतपुराण ; also Śrīmad Bh āgavata Mah ā Pur āṇa, Śrīmad Bh āgavatam or Bh āgavata ) is one of Hinduism 's eighteen great Puranas (Mahapuranas , great histories).[1][2] Composed in Sanskrit and available in almost all Indian languages,[3] it promotes bhakti (devotion) to Krishna [4][5][6] integrating themes from the Advaita (monism) philosophy of Adi Shankara .[5][7][8] The Bhagavata Purana , like other puranas, discusses a wide range of topics including cosmology, genealogy, geography, mythology, legend, music, dance, yoga and culture.[5][9] As it begins, the forces of evil have won a war between the benevolent devas (deities) and evil asuras (demons) and now rule the universe. Truth re-emerges as Krishna, (called " Hari " and " Vasudeva " in the text) – first makes peace with the demons, understands them and then creatively defeats them, bringing back hope, justice, freedom and good – a cyclic theme that appears in many legends.[10] The Bhagavata Purana is a revered text in Vaishnavism , a Hindu tradition that reveres Vishnu.[11] The text presents a form of religion ( dharma ) that competes with that of the Vedas , wherein bhakti ultimately leads to self-knowledge, liberation ( moksha ) and bliss.[12] However the Bhagavata Purana asserts that the inner nature and outer form of Krishna is identical to the Vedas and that this is what rescues the world from the forces of evil.[13] An oft-quoted verse is used by some Krishna sects to assert that the text itself is Krishna in literary -

Vidura, Uddhava and Maitreya

Çré Çayana Ekädaçé Issue no: 17 27th July 2015 Vidura, Uddhava and Maitreya Features VIDURA QUESTIONS UDDHAVA Srila Sukadeva Goswami THE MOST EXALTED PERSONALITY IN THE VRISHNI DYNASTY Lord Krishna instructing Uddhava Lord Sriman Purnaprajna Dasa UDDHAVA REMEMBERS KRISHNA Srila Vishvanatha Chakravarti Thakur UDDHAVA GUIDES VIDURA TO TAKE SHELTER OF MAITREYA ÅñI Srila Sukadeva Goswami WHY DID UDDHAVA REFUSE TO BECOME THE SPIRITUAL MASTER OF VIDURA? His Divine Grace A .C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada WHY DID KRISHNA SEND UDDHAVA TO BADRIKASHRAMA? Srila Vishvanatha Chakravarti Thakur WHO IS MAITREYA ÅñI? Srila Krishna-Dvaipayana Vyasa Issue no 16, Page — 2 nityaà bhägavata-sevayä VIDURA QUESTIONS UDDHAVA be the cause of the Åg Veda, the creator of the mind Srila Sukadeva Goswami and the fourth Plenary expansion of Viñëu. O sober one, others, such as Hridika, Charudeshna, Gada and After passing through very wealthy provinces like the son of Satyabhama, who accept Lord Sri Krishna Surat, Sauvira and Matsya and through western India, as the soul of the self and thus follow His path without known as Kurujangala. At last he reached the bank of deviation-are they well? Also let me inquire whether the Yamuna, where he happened to meet Uddhava, Maharaja Yudhisthira is now maintaining the kingdom the great devotee of Lord Krishna. Then, due to his great according to religious principles and with respect love and feeling, Vidura embraced him [Uddhava], for the path of religion. Formerly Duryodhana was who was a constant companion of Lord Krishna and burning with envy because Yudhisthira was being formerly a great student of Brihaspati's. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Prayers by Akrura

Prayers by Akrura Venue: Los Angeles So, we welcome you one more time on my behalf also, on the occasion of the concluding session of Srimad Bhagvat Katha Mohotsava here at Los Angeles temple at the lotus feet of the Lordships Shri Shri Rukmini Dwarkadish and in presence of His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Srila Prabhupad ki jai! So, we will continue from where we had left off yesterday. So Gopis did try their best to stop the Lord from going to Mathura. However, Lord had his duty to perform “vinasayaca duskrtam dharmasansthapanarthaya sambhavami yuge yuge” (4.8) Now, he had taken care of quite a few of the dushtas, asuras, the demoniac personalities. However, the leader of them was still hanging around, he was around. Right there in his capital and he was the one, who had invited, He had his whole idea of just do cover up, make sound like festival, big festival in Mathura. Please come! We will have a fire sacrifice also and lot’s of prasadam distribution, you bring (laugh). You bring the milk products, you distribute, you share. Lots of fun, big town! Please come! See Mathura town! And he had sent chariot for Krishna and Balarama, so as he had his plan, “Man proposes and God…” So God had His plan, and everything was working out as per His plan. So they were seated in the chariot, Krishna and Balarama and Akrur was “rathena vayu-vegena,” the ratha, the chariot of this Krishna and Balarama was moving speedily, what was the speed? “vayu- vegena” like a wind, very fast. -

Vrindaban Days

Vrindaban Days Memories of an Indian Holy Town By Hayagriva Swami Table of Contents: Acknowledgements! 4 CHAPTER 1. Indraprastha! 5 CHAPTER 2. Road to Mathura! 10 CHAPTER 3. A Brief History! 16 CHAPTER 4. Road to Vrindaban! 22 CHAPTER 5. Srila Prabhupada at Radha Damodar! 27 CHAPTER 6. Darshan! 38 CHAPTER 7. On the Rooftop! 42 CHAPTER 8. Vrindaban Morn! 46 CHAPTER 9. Madana Mohana and Govindaji! 53 CHAPTER 10. Radha Damodar Pastimes! 62 CHAPTER 11. Raman Reti! 71 CHAPTER 12. The Kesi Ghat Palace! 78 CHAPTER 13. The Rasa-Lila Grounds! 84 CHAPTER 14. The Dance! 90 CHAPTER 15. The Parikrama! 95 CHAPTER 16. Touring Vrindaban’s Temples! 102 CHAPTER 17. A Pilgrimage of Braja Mandala! 111 CHAPTER 18. Radha Kund! 125 CHAPTER 19. Mathura Pilgrimage! 131 CHAPTER 20. Govardhan Puja! 140 CHAPTER 21. The Silver Swing! 146 CHAPTER 22. The Siege! 153 CHAPTER 23. Reconciliation! 157 CHAPTER 24. Last Days! 164 CHAPTER 25. Departure! 169 More Free Downloads at: www.krishnapath.org This transcendental land of Vrindaban is populated by goddesses of fortune, who manifest as milkmaids and love Krishna above everything. The trees here fulfill all desires, and the waters of immortality flow through land made of philosopher’s stone. Here, all speech is song, all walking is dancing and the flute is the Lord’s constant companion. Cows flood the land with abundant milk, and everything is self-luminous, like the sun. Since every moment in Vrindaban is spent in loving service to Krishna, there is no past, present, or future. —Brahma Samhita Acknowledgements Thanks go to Dr. -

Granny, I Have Been Reading Our 48Th Imam, Mowlana Sultan Mohamed Shah (Alayhi Salam)’S Holy Farmans and Very Often, I Have Come Across the Word Himmat

Courage is a Must [Part Two] By Alysha Javer with her grandmother Zeenatara Allakrakhyavia “Granny, I have been reading our 48th Imam, Mowlana Sultan Mohamed Shah (alayhi salam)’s holy farmans and very often, I have come across the word himmat . According to the Imam, it is vital for a true mom’in to have himmat. So one must have courage if one wants to be counted as a true mom’in. I have thought about this a lot but have not quite been able to exactly work out the inferences contained within this one simple sentence in the Imam’s holy farmans. Please help me out by sharing with me your thoughts about this.” In conclusion to her ideas (already expressed in Part One: http://wp.me/p1Z38-eRH), my grandmother’s final directive on this subject was very simple: “Go back in history and know the story of Sudama. Everything will fall into place.” I thus decided to research on this story and in this article, which represents the second part of my grandmother’s thoughts on the subject of himmat (courage), I share with you the story of Sudama – the childhood friend of Lord Shri Krishna. I have used several sources to compile this story and I beg deference if some parts of the story may appear plagiarised from known popular sources. I would like to deeply express my gratitude to my grandmother for pointing me in the direction of this greatly courageous man whose life and choices will form a source of great inspiration to myself and, I hope, to all those who make the time to read his story via this article. -

THE VISHNU PURANA the Vishnu Purana Has Twenty-Three Thousand

THE VISHNU PURANA The Vishnu Purana has twenty-three thousand shlokas. Skanda Purana has eighty-one thousand shloka and Markandeya Purana only nine thousand. The Vishnu Purana also has six major sections or amshas, although the last of these is really short. Maitreya and Parashara Once the sage Maitreya came to the sage Parashara and wanted to know about the creation of the universe. And this is what Parashara told him. In the beginning the universe was full of water. But in that water there emerged a huge egg (anda) that was round like a water-bubble. The egg became bigger and bigger and inside the egg there was Vishnu. This egg was called Brahmanda. And inside Brahmanda there were the mountains and the land, the oceans and the seas, the gods, demons and humans and the stars. On all sides, the egg was surrounded by water, fire, wind, the sky and the elements. Inside the egg, Vishnu adopted the form of Brahma and proceeded to create the universe. When the universe is to be destroyed, it is Vishnu again who adopts the form of Shiva and performs the act of destruction. Let us therefore salute the great god Vishnu. There are four yugas or eras. These are called krita (or satya), treta, dvapara and kali. Krita era consists of four thousand years, treta of three thousand, dvapara of two thousand and kali of one thousand. All the four eras thus pass in ten thousand. And when all the four eras have passed one thousand times each, that is merely one day for Brahma. -

The Glories of Sri Vrindavan Meeting of Vajranabha and Parikshit the Glories of Sri Vrindavan Srila Suta Goswami Srila Narahari Cakravarti Thakura

Çré Indira Ekädaçé Issue no:96 5th October 2018 THE GLORIES OF SRI VRINDAVAN MEETING OF VAJRANABHA AND PARIKSHIT THE GLORIES OF SRI VRINDAVAN Srila Suta Goswami Srila Narahari Cakravarti Thakura HOW VAJRANABHA ESTABLISHED Uddhava Sandeśa BRAJMANDALA? Srila Rupa Goswami Sri Rajashekhara Das Adhikari SEEING SRI VRINDAVAN His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Issue no 96, Page — 2 nityaà bhägavata-sevayä MEETING OF VAJRANABHA AND PARIKSHIT have one problem. Kindly consider the Srila Suta Goswami following matter. Although I've been installed as the King Desiring to see Vajranabha, Maharaja of Mathura, I feel like I am living in a Pariksit once went to the city of Mathura. forest. The happiness of a kingdom is due Hearing that Maharaja Pariksit, who was to the presence of the great people that equal to his own father, was coming to live there. Unfortunately, I have no idea see him, Vajranabha's heart filled with where the great residents of this place affection. He went to the city gate, fell have now gone.” at Maharaja Pariksit's feet, and then Hearing Vajranabha's words, Maharaja brought him to his palace. The great Pariksit called for Shandilya Rishi as he hero Maharaja Pariksit, who was always knew the sage could clear Vajranabha's absorbed in thoughts of Lord Krishna, doubts. Shandilya Rishi had previously lovingly embraced Vajranabha. They acted as the priest for Nanda Maharaja and together entered the inner palace and the cowherd men and thus he knew the offered obeisance to Rukmini, the chief truths of Vrindavan. When he received the of Lord Krishnas one hundred and eight message from Pariksit Maharaja, Shandilya wives. -

Raebarely Brick Kiln Details 05.09.14

{ks=h; dk;kZy; jk;cjsyh ds vUrxZr fLFkr bZaV HkV~Bksa dk fooj.k dze {ks=h; dk;kZy; tuin bZaV HkV~Bksa dk uke irs lfgr ,u0vks0lh0@ ,u0vks0lh0@ ,u0vks0lh0@ lgeft dc rd uksfVl@cUnh vkns'k fuxZr djus ifjokn laoU/kh fooj.k la[;k dk uke lgefr lgefr tkjh djus dh lgefr vkosnu vLohd`r dh fLFkfr frfFk lfgr ;fn ifjokn nk;j dqy vkosnu i= izkfIr dh frfFk djus lacU/kh fooj.k fd;k frfFk x;k gS rks mldh frfFk dk;Zokgh@frfFk 1 Regional Office Raebareli A.K. Brick Field, Vill. Mouhari Majare Bela khara, Tehsil & Distirct Raebareli. 01.12.12 04.12.12 _ 31.12.16 Raebareli 2 Regional Office Raebareli Abhaydata Brick Field, Vill. Bashar, Post Sanahi, Tehsil Sadar, Raebareli. 03.01.11 10.01.11 _ 31.12.15 Raebareli 3 Regional Office Raebareli Abhishek Brick Field, Vill. Bhatnaus, Tikariya, Salon, Raebareli. 23.08.14 pending pending Raebareli 4 Regional Office Raebareli Abhishek Brick Field, Vill. Behatramau, Unchahar, Raebareli. 26.03.10 26.04.10 _ 31.12.14 Raebareli 5 Regional Office Raebareli Ajad Brick Field, Vill. Bagaha, Post Mataka, Tehsil Salon, Raebareli. 31.05.10 04.06.10 _ 31.12.14 Raebareli 6 Regional Office Raebareli Ajay Brick Field, Vill. Malikmau Chaubara, Tehsil, Sadar, Raebareli. 22.05.10 28.05.10 _ 31.12.14 Raebareli 7 Regional Office Raebareli Ajay Brick Field, Vill. Shobhvapur (Dosadaka) Lalganj, Raebareli. 23.03.10 16.04.10 _ 31.12.14 Raebareli 8 Regional Office Raebareli Aman Brick Field, Vill. -

Mandir Vani of NWA : Volume 1 Issue 1 May 2012 Send Suggestions/ Contributions To: [email protected]

Temple Address: 2500 SW Regional Airport Blvd. Bentonville, AR 72712 Mookam Karoti Vachalam,, Pangum Langhayate Girim. Temple Hours: Saturdays from 5 PM to 8 PM Sundays from 10 AM to 1 PM Yat Krupa Tamaham Vande, Paramanand Madhavam. Vishnu Sahasranamam: Every Saturday at 6 PM Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.nwahindutemple.org Salutations to the ultimate bliss Madhava, by whose grace, a dumb man becomes the most talkative and a physically disabled man crosses the highest mountain. Driving Directions to the new Temple from Exit 85 Rogers/Bentonville 1. Take I-540, EXIT 85, towards AIRPORT/ROGERS/BENTONVILLE. 0.3 mi 2. Turn West onto US-71 BR/AR-12/W WALNUT ST/SE WALTON BLVD. Continue to follow vakratunda mahaakaaya suryakoti samaprabhaa. US-71 BR/AR-12/SE WALTON BLVD. 1.5 mi nirvighnam kurumedeva sarvakaaryeshu sarvadaa.. 3. Turn LEFT onto SW REGIONAL AIRPORT BLVD/AR-12. 1.7 mi 4. 2500 SW REGIONAL AIRPORT BLVD is on the RIGHT opposite to World's Gym. Temple News Isn't it exciting to see our New Temple sprout up so fast? Isn’t it Lord’s grace that made us see the fruition? Let us keep praying for strength, patience, power of wealth and devotion to see our successful Grand opening of the new Temple. We know each of you is so excited to see our dream in reality and HANWA is so glad to fulfill your desire to have the New Temple Sneak Preview. HANWA is conducting sneak preview sessions and please keep an eye for your turn to receive the invitation. -

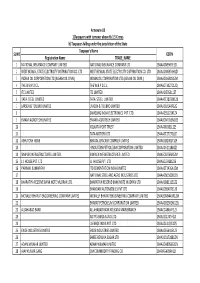

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO.