Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book a Sense of the World : How a Blind Man Became Historys

A SENSE OF THE WORLD : HOW A BLIND MAN BECAME HISTORYS GREATEST TRAVELER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jason Roberts | 379 pages | 01 Jun 2007 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007161263 | English | London, United Kingdom A Sense of the World : How a Blind Man Became Historys Greatest Traveler PDF Book Holman had a loose idea of his circumnavigation route: spend winter in western Russia, traverse Siberia the following spring, pass through Mongolia, sneak into China, hop on a whaling ship set for Hawaii, and improvise onward. Raised near an apothecary in Exeter, England, Holman enjoyed a healthy childhood and enlisted with the Royal Navy at age Holman was a hurricane of audacity, goodwill, and charm. Holman asked who would pay for the wheezing animal. Stock photo. Add links. Holman's charm and cunning nets him excursions to the Americas, Africa and the Orient - hunting slave A chance encounter in a library led the author to discover James Holman — In Nice, he harvested grapes on a vineyard estate. It entered into my heart, and I could have wept, not that I did not see, but that I could not portray all that I felt. He was famous in his day as "the Blind Traveler," but slipped into obscurity after his death in I have shared the joy and surprise of finding sounds, languages, twilights, cities, gardens and people, all of them distinctly different and unique p. He visited art museums, toured cathedrals, and hiked mountains. I can't fault the author's choice of subject, nor his research, nor his writing skills per se he's an accomplished journalist and graceful storyteller. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

A Society Wedding in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1910

A society wedding in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1910. By the end of the 17th century, white had become identified with maidenly innocence. But pink, blue, and yellow bridal dresses persisted until the late 19th century, when "white weddings1'-with bridesmaids, the best man, and composer Richard Wagner's "Bridal Chorusw-became an established tradition. Defining "tradition" is no easy matter. Sociologist Edward Shils called it "anything which is transmitted or handed down from the past to the present." In Chinese weddings as in the U.S. Ma- rine Corps, beliefs, images, social practices, and institutions may all partake of the traditional. Yet the symbols and rituals are less important than the human motives that guide their transmission down through the ages. Tradition may simply function as a means of promoting social stability and continuity. On the other hand, scholars note, it may be deliberately developed and culti- vated as a way of rewriting the past in order to justify the present. Here, in two case studies, Hugh Trevor-Roper and Terence Ran- ger suggest that what we now regard as "age-old" traditions may have their origins in inventive attempts to "establish or legiti- mize . status or relations of authority." by Hugh Trevor-Roper Today, whenever Scotsmen gather together to celebrate their national identity, they wear the kilt, woven in a tartan whose colors and pattern indicate their clan. This apparel, to which they ascribe great antiquity, is, in fact, of fairly recent ori- gin. Indeed, the whole concept of a distinct Highland culture and tradition is a retrospective invention. -

Antiquaries in the Age of Romanticism: 1789-1851

Antiquaries in the Age of Romanticism: 1789-1851 Rosemary Hill Queen Mary, University of London Submitted for the degree of PhD March 2011 1 I confirm that the work presented in this thesis and submitted for the degree of PhD is my own. Rosemary Hill 2 Abstract The thesis concentrates on the work of fourteen antiquaries active in the period from the French Revolution to the Great Exhibition in England, Scotland and France. I have used a combination of the antiquaries’ published works, which cover, among other subjects, architecture, topography, costume history, Shakespeare and the history of furniture, alongside their private papers to develop an account of that lived engagement with the past which characterised the romantic period. It ends with the growing professionalistion and specialisation of historical studies in the mid-nineteenth century which left little room for the self-generating, essentially romantic antiquarian enterprise. In so far as this subject has been considered at all it has been in the context of what has come to be called ‘the invention of tradition’. It is true that the romantic engagement with history as narrative led to some elaboration of the facts, while the newness of the enterprise laid it open to mistakes. I have not ignored this. The restoration of the Bayeux Tapestry, the forged tartans of the Sobieski Stuarts and the creation of Shakespeare’s Birthplace are all considered. Overall, however, I have been concerned not to debunk but as it were to ‘rebunk’, to see the antiquaries in their historical context and, as far as possible, in their own terms. -

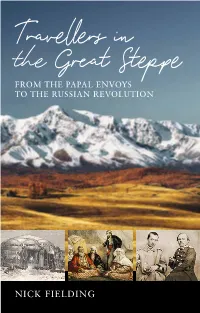

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Gaelic Views

Gaelic views Follow the gold numbers on the floor to locate the featured objects and themes Gallery plan 16 15 14 17 18 13 Royal favour 12 19 11 A tour of 20 Scotland 10 21 A romantic vision 9 of Scotland 7 22 8 3873 6 4 23 5 3 The Highland ideal Scotland after Culloden 26 24 25 27 2 1 Wild and Majestic: Romantic visions of Scotland Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland 1 Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland Symbols of Scotland These images and objects tell us immediately how a culture came into being in Scotland that was rooted in the traditional culture of the Highlands. But these ‘roots’ are still a matter of contention. How deep do they really go? Do they derive from an ancient culture that was truly Gaelic? Or was this culture created in the Romantic era? We see weaponry, tartans, a painting and a bagpipe. To an extent each item is a new creation: the new tourist view over Loch Katrine in about 1815; sword designed in the 18th century; a dress sense growing out of army uniforms in the years when Highland dress and tartan was proscribed; and a Highland bagpipe in a new style created about 1790. Certainly, the impact of recent fashions was clear to see. But Gaels would still recognise that each piece, to a greater or lesser extent, formed part of their heritage. Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland 2 The Piper and Champion to the Laird of Grant In the wake of the Jacobites The British government had their reason to pass laws against Highland dress after Culloden. -

PICKLE the SPY Or the Incognito of Prince Charles 'I

PICKLE THE SPY or The Incognito of Prince Charles ‘I knew the Master: on many secret steps of his career I have an authentic memoir in my hand.’ THE MASTER OF BALLANTRAE PREFACE This woful History began in my study of the Pelham Papers in the Additional Manuscripts of the British Museum. These include the letters of Pickle the Spy and of JAMES MOHR MACGREGOR. Transcripts of them were sent by me to Mr. ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON, for use in a novel, which he did not live to finish. The character of Pickle, indeed, like that of the Master of Ballantrae, is alluring to writers of historical romance. Resisting the temptation to use Pickle as the villain of fiction, I have tried to tell his story with fidelity. The secret, so long kept, of Prince Charles’s incognito, is divulged no less by his own correspondence in the Stuart MSS. than by the letters of Pickle. For Her Majesty’s gracious permission to read the Stuart Papers in the library of Windsor Castle, and to engrave a miniature of Prince Charles in the Royal collection, I have respectfully to express my sincerest gratitude. To Mr. HOLMES, Her Majesty’s librarian, I owe much kind and valuable aid. The Pickle Papers, and many despatches in the State Papers, were examined and copied for me by Miss E. A. IBBS. In studying the Stuart Papers, I owe much to the aid of Miss VIOLET SIMPSON, who has also assisted me by verifying references from many sources. It would not be easy to mention the numerous correspondents who have helped me, but it were ungrateful to omit acknowledgment of the kindness of Mr. -

The Holmans in America : Concerning the Descendants of Solaman

yiij;iljiilil;:,ii]l,iili;iyillil!lllll , Gc 3 1833 01363 3596 929.2 I H731h v.l 1129678 REYNOLDS HISTORICAL GENEALOGY COLLECTION THE HOLMANS IN AMERICA VOLUME ONE 1 THE HOLMANS IN AMERICA CONCERNING THE DESCENDANTS OF SOLAMAN HOLMAN WHO SETTLED IN WEST NEWBURY, MASSACHUSETTS, IN 1692-3, ONE OF WHOM IS WILLIAM HOWARD' TAFT, THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES. INCLUDING A PAGE OF THE OTHER LINES OF HOLMANS IN AMERICA, WITH NOTES AND ANECDOTES OF THOSE OF THE NAME IN OTHER COUNTRIES. DAVID EMORY HOLMAN, M. D. or Attlebobo, MASSACHnsiTTS, U. S. A. VOLUME ONE THE GRAFTON PRESS GENEALOGICAL PUBLISHERS NEW YORK Copyright, 1909, By DAVID EMORY HOLMAN — 1129678 To My Deaelt Beloved Brother FRANK HOLMAN who has aided me always by his high artistic ideals and rare memory, and by his great interest in the work and de- sire that it should not be commonplace —and to the noble and generous mem- bees of the family, who have given of their time and thought to make this record of our race more complete This Volume Is Most Sincerely Dedicated ABBREVIATIONS adm Administration g. s Grave Stone bap Baptized int Intention of Marriage, or b Born Interred B. G Burying Ground m Married ch Children m. n. (m. n.) . .Maiden Name c. r Church Record P Page dau Daughter prob. ( prob. ) . Probate, or probably d Died ref Reference d. y Died Young s Son of f Form unm Unmarried fam. b Family Bible V. s Vital Statistics f . r Family Record CONTENTS PAOE Preface xi Introduction xiii Origin of the Name xv Camdens (England) Society Publications xvi " " Lieut. -

Don't Take the High Road: Tartanry and Its Critics David Goldie If You W

Don’t take the High Road: Tartanry and its Critics David Goldie If you were of a religious persuasion and had a sense of humour you might think tartan to be one of God’s better jokes. To match up this gaudy, artificial, eye- strainingly irrational fabric with a countryside characterised by its mists and rains and a correspondingly rather dour people known throughout the world for canniness, pragmatism, and rationality, seems a rather sublime piece of audacity and one that can hardly be explained by the normal historical means. It’s true that there may be material historical reasons for tartan, that an impoverished people might weave a kind of textile bricolage from whatever stray fibres might come to hand, for example, and it’s also plausible that muted tartans might have a practical role as an effective camouflage. But this is still quite far from explaining how a piece of such abstract and unwarranted extravagance as ‘Ye principal clovris of ye clanne Stewart tartan’ might have come into being.1 In a similar vein it’s entirely credible to argue that the heady collision of Sir Walter Scott, King George IV, and European Romanticism in Edinburgh in 1822 explains much about tartanry’s sentimental vulgarity and its weird mixture of ostentation and supplication. But what remains seemingly beyond the range of explication (and what Scott already sensed in his fiction) is the fundamental, almost ridiculous mismatch between this impractical concoction and its symbolic importance to a nation seeking to build an international reputation on its hard practical skills in engineering, industrial chemistry, and finance. -

Class of 2021

THE UNIVERSITY of MISSISSIPPI One Hundred Sixty-Eighth COMMENCEMENT Saturday, the First of May 2021 THE UNIVERSITY of MISSISSIPPI TM One Hundred Sixty-Eighth COMMENCEMENT Saturday, the First of May 2021 Office of the Chancellor On behalf of the faculty and staff of the University of Mississippi, we extend a sincere welcome to the students, parents, families and friends gathered to celebrate the university’s 168th Commencement. We are pleased to recognize the spirit of our community and honor the academic accomplishments and dedication of our beloved candidates for graduation of the Class of 2021. Commencement is a time-honored tradition that recognizes the outstanding work and achievements of students and faculty. It is an exciting time for us, and we know this is a special occasion for all of you. Our students are the heart and soul of Ole Miss, and we take pride and inspiration in their accomplishments and growth. Today’s ceremony celebrates years of study, hard work and careful preparation, and we’re grateful that you have come to show your support, love and belief in these graduates. The members of the Class of 2021 accomplished so much during their time as Ole Miss students — they pursued their passions, maximized their potential and pushed their boundaries through outstanding learning opportunities and life-changing experiences. In addition, they endured the disruption caused by the pandemic, which has taught us all important life lessons about resilience and the need to be adaptable. Now, we can’t wait to see how they’ll build and grow personal legacies of achievement, service and leadership. -

Type 'In Confidence'

Historical scientific research on disability at the Royal Society “Travelling blind”, James Holman FRS (1785/6-1857) Scientists are fascinated by observing the world and this is one of the fundamental tools of the scientific method. Unsurprisingly, many have travelled the globe and written about it in both scientific and popular accounts. Cook’s Endeavour voyage and Charles Darwin’s journey of discovery aboard HMS Beagle resulted in some of the most famous examples of this kind of genre writing. But one of the most remarkable travelling-author Fellows of the Royal Society was not sighted: James Holman (1785/6-1857) who became celebrated and known to his contemporaries as ‘the blind traveller’. James Holman by R Cooper after Madame Fabroni, 1825/The Royal Society Holman was an Oxford-educated Royal Navy lieutenant serving aboard ship until 1807 when ill-health meant that he was invalided out of his maritime profession. The nature of his condition is not known, but Holman had some apparent difficulties in physical mobility and became completely blind at around twenty-four years of age. He refused a quiet retirement in Windsor in favour of restless journeying: “the desire of locomotion has to him become a new sense – a compensating principle...”. Holman travelled to Europe initially but would eventually circumnavigate the world, writing popular books about his experiences and impressions. James Holman by Edward Francis Finden after Thomas Charles Wageman, c.1834/The Royal Society credit Engraved by Edward Francis Finden (1791-1857) British printmaker after Thomas Charles Wageman (1787-1853) English artist Later biographical accounts of Lieutenant Holman have tended to concentrate on the novelty of his situation as a solo adventurer and on the more arduous aspects of his journeying. -

Landscape and History Since 1500 Ian D

Landscape and History since IAND. WHYTE landscape and history globalities Series editor: Jeremy Black globalities is a series which reinterprets world history in a concise yet thoughtful way, looking at major issues over large time-spans and political spaces; such issues can be political, ecological, scientific, technological or intellectual. Rather than adopting a narrow chronological or geographical approach, books in the series are conceptual in focus yet present an array of historical data to justify their arguments. They often involve a multi-disciplinary approach, juxtaposing different subject-areas such as economics and religion or literature and politics. In the same series Why Wars Happen Mining in World History Jeremy Black Martin Lynch A History of Language China to Chinatown: Chinese Food Steven Roger Fischer in the West J. A. G. Roberts The Nemesis of Power Harald Kleinschmidt Geopolitics and Globalization in the Twentieth Century Brian W. Blouet Monarchies 1000–2000 W. M. Spellman A History of Writing Steven Roger Fischer The Global Financial System 1750 to 2000 Larry Allen Landscape and History since 1500 ian d. whyte reaktion books For Kathy, Rebecca and Ruth Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 79 Farringdon Road, London ec1m 3ju, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2002 Copyright © Ian D. Whyte 2002 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and King’s Lynn British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Whyte, I.