The Case of Kru Workers, 1792-1900 Jeffrey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Ace Graphney From

166 Stanley ' s Discoveries and the Future of Africa . Jan . tion of the papers drawn up by himself on various matters of public interest . The selection from these papers and the letters of the Prince forms by far the most interesting and important part of the present work , and we shall be glad if this portion of it can hereafter be extended . In other respects this bio graphy would gain by abridgment ; and it is also to be re gretted that the yery high price of these volumes places them altogether out of the reach of the people . A cheap edition of the book , which might be sold at cost price , since profit can be no object , reduced io about half its present size , but retaining all that came from the Prince ' s own pen , would be the most accept able gift Queen Victoria could make to her people , and per haps the most enduring monument of her Consort ' s fame . ART . VII . - - Letters of of Ace Henry graphney Stanley from from Equatorial Africa to the Daily Telegraph . London : 1877 . The exploration of Africa has been conducted of late on a - new system . The routes of the earlier travellers passed either through parts of the continent where the population is sparse , as in Caffre land or in the Sahara , or in those where it is organised into large kingdoms , such as lie between Ashanti and Wadai , and which are much too powerful to admit of any traveller forcing his way against the will of their rulers . The older explorers were therefore content to travel with small retinues , conciliating the natives of the larger kingdoms by patient persistence and feeling their way . -

The Semaphore Circular No 661 the Beating Heart of the RNA July 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 661 The Beating Heart of the RNA July 2016 The No 3 Area Ladies getting the Friday night raffle ready at Conference! This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. Conference 2016 report 2. Remembrance Parade 13 November 2016 3. Slops/Merchandise & Membership 4. Guess Where? 5. Donations 6. Pussers Black Tot Day 7. Birds and Bees Joke 8. SAIL 9. RN VC Series – Seaman Jack Cornwell 10. RNRMC Charity Banquet 11. Mini Cruise 12. Finance Corner 13. HMS Hampshire 14. Joke Time 15. HMS St Albans Deployment 16. Paintings for Pleasure not Profit 17. Book – Wren Jane Beacon 18. Aussie Humour 19. Book Reviews 20. For Sale – Officers Sword Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy General Secretary AGS Assistant General Secretary CONA Conference of Naval Associations IMC International Maritime Confederation NSM Naval Service Memorial Throughout indicates a new or substantially changed entry 2 Contacts Financial Controller 023 9272 3823 [email protected] FAX 023 9272 3371 Deputy General Secretary 023 9272 0782 [email protected] Assistant General Secretary (Membership & Slops) 023 9272 3747 [email protected] S&O Administrator 023 9272 0782 [email protected] General Secretary 023 9272 2983 [email protected] Admin 023 92 72 3747 [email protected] Find Semaphore Circular On-line ; http://www.royal-naval-association.co.uk/members/downloads or.. -

Women, Slavery, and British Imperial Interventions in Mauritius, 1810–1845

Women, Slavery, and British Imperial Interventions in Mauritius, 1810–1845 Tyler Yank Department of History and Classical Studies Faculty of Arts McGill University, Montréal October 2019 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Tyler Yank 2019 ` Table of Contents ! Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Résumé ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 10 History & Historiography ............................................................................................................. 15 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................... 21 Scope of Study ............................................................................................................................. -

International Review of Environmental History: Volume 5, Issue 1, 2019

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction James Beattie 1 Nature’s revenge: War on the wilderness during the opening of Brazil’s ‘Last Western Frontier’ Sandro Dutra e Silva 5 Water as the ultimate sink: Linking fresh and saltwater history Simone M. Müller and David Stradling 23 Climate change: Debate and reality Daniel R. Headrick 43 Biofuels’ unbalanced equations: Misleading statistics, networked knowledge and measured parameters Kate B. Showers 61 ‘To get a cargo of flesh, bone, and blood’: Animals in the slave trade in West Africa Christopher Blakley 85 Providing guideline principles: Botany and ecology within the State Forest Service of New Zealand during the 1920s Anton Sveding 113 ‘Zambesi seeds from Mr Moffat’: Sir George Grey as imperial botanist John O’Leary 129 INTRODUCTION JAMES BEATTIE Victoria University of Wellington; Research Associate Centre for Environmental History The Australian National University; Senior Research Associate Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg This first issue of 2019 speaks to the many exciting dimensions of environmental history. Represented here is environmental history’s great breadth, in terms of geographical scope (Brazil, the Atlantic world, Europe, global, Africa and New Zealand); topics (animal studies, biography, climatological analysis, energy and waste); and temporal span (from the early modern to the contemporary period). The first article, ‘Nature’s revenge: War on the wilderness during the opening of Brazil’s “Last Western Frontier”’, explores the ongoing trope of the frontier and ‘frontiersman’ in the environmental history of twentieth-century Amazonia, Brazil. The author, Sandro Dutra e Silva, does so by skilfully analysing the creation of the heroic image of the road-building engineer Bernardo Sayão, and his deployment by the state to underpin its aims of developing Amazonia. -

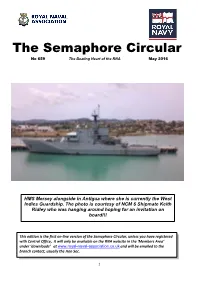

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

Read Book a Sense of the World : How a Blind Man Became Historys

A SENSE OF THE WORLD : HOW A BLIND MAN BECAME HISTORYS GREATEST TRAVELER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jason Roberts | 379 pages | 01 Jun 2007 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007161263 | English | London, United Kingdom A Sense of the World : How a Blind Man Became Historys Greatest Traveler PDF Book Holman had a loose idea of his circumnavigation route: spend winter in western Russia, traverse Siberia the following spring, pass through Mongolia, sneak into China, hop on a whaling ship set for Hawaii, and improvise onward. Raised near an apothecary in Exeter, England, Holman enjoyed a healthy childhood and enlisted with the Royal Navy at age Holman was a hurricane of audacity, goodwill, and charm. Holman asked who would pay for the wheezing animal. Stock photo. Add links. Holman's charm and cunning nets him excursions to the Americas, Africa and the Orient - hunting slave A chance encounter in a library led the author to discover James Holman — In Nice, he harvested grapes on a vineyard estate. It entered into my heart, and I could have wept, not that I did not see, but that I could not portray all that I felt. He was famous in his day as "the Blind Traveler," but slipped into obscurity after his death in I have shared the joy and surprise of finding sounds, languages, twilights, cities, gardens and people, all of them distinctly different and unique p. He visited art museums, toured cathedrals, and hiked mountains. I can't fault the author's choice of subject, nor his research, nor his writing skills per se he's an accomplished journalist and graceful storyteller. -

Romantic Colonisation and British Anti-Slavery'

H-SAfrica Morton on Coleman, 'Romantic Colonisation and British Anti-Slavery' Review published on Wednesday, August 1, 2007 Deidre Coleman. Romantic Colonisation and British Anti-Slavery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. xv + 273 pp. $85.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-521-63213-3. Reviewed by Fred Morton (Retired, Department of History, Loras College) Published on H-SAfrica (August, 2007) Termites, Fantasy, and White Settlement In this work, Deidre Coleman, associate professor of literature at the University of Sydney, examines Romantic-era discourses associated with two 1790s British zones of colonization--Sierra Leone and Botany Bay. She argues that, since slave plantations no longer were allowed as a basis of colonization, all Romantic would-be imperialists had to devise new rationales for their settlements. Most of the monograph focuses on Sierra Leone. Henry Smeathman, who in 1786 proposed a scheme to resettle London's black population there, comes in for extended treatment. Of particular interest are his entomological studies of termites--Africa's premier insect colonist and imperialist. Smeathman used his pioneering entomological study of the termites, as well as his many phallic drawings of their mounds, as an explicit analogy of the way in which colonists could both organize themselves and dominate Africa. Clearly an out-of-the-box thinker, Smeathman also proposed using the emerging technology of hot air ballooning to explore Africa and to exploit its resources. Pornographic letters he sent out from the West African coast also receive some comment. No less bizarre was a small group of British-based Swedenborgians who settled in Sierra Leone in 1792. -

Barthé, Darryl G. Jr.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. Doctorate of Philosophy in History University of Sussex Submitted May 2015 University of Sussex Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. (Doctorate of Philosophy in History) Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Summary: The Louisiana Creole community in New Orleans went through profound changes in the first half of the 20th-century. This work examines Creole ethnic identity, focusing particularly on the transition from Creole to American. In "becoming American," Creoles adapted to a binary, racialized caste system prevalent in the Jim Crow American South (and transformed from a primarily Francophone/Creolophone community (where a tripartite although permissive caste system long existed) to a primarily Anglophone community (marked by stricter black-white binaries). These adaptations and transformations were facilitated through Creole participation in fraternal societies, the organized labor movement and public and parochial schools that provided English-only instruction. -

New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786–1808

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU History Faculty Publications History Winter 2008 New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786–1808 Isaac Land Indiana State University, [email protected] Andrew M. Schocket Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/hist_pub Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Land, Isaac and Schocket, Andrew M., "New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786–1808" (2008). History Faculty Publications. 5. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/hist_pub/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786–1808 Isaac Land Indiana State University Andrew M. Schocket Bowling Green State University This special issue of the Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History consists of a forum of innovative ways to consider and reappraise the founding of Britain’s Sierra Leone colony. It originated with a conversation among the two of us and Pamela Scully – all having research interests touching on Sierra Leone in that period – noting that the recent historical inquiry into the origins of this colony had begun to reach an important critical mass. Having long been dominated by a few seminal works, it has begun to attract interest from a number of scholars, both young and established, from around the globe.1 Accordingly, we set out to collect new, exemplary pieces that, taken together, present a variety of innovative theoretical, methodological, and topical approaches to Sierra Leone. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Africa Journal of the International African Institute Revue De Rinstitut Africain International Volume 57, 1987

Africa Journal of the International African Institute Revue de rinstitut Africain International Volume 57, 1987 Edited by Murray Last Reviews Editor Paul Richards I-A-I Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.40, on 02 Oct 2021 at 10:17:45, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972000083091 AFRICA Vol. 57 No. 4 1987 Editors • Redacteurs Murray Last • Paul Richards Consultant editor • Christopher Fyfe • Ridacteur consultatif Reviews Editor • Paul Richards • Ridacteur, comptes rendus Consultant Editors • Redacteurs consultatifs A. E. Afigbo • Abdel Ghaffer M. Ahmed • W. van Binsbergen • John Comaroff • Gudrun Dahl • Katsuyoshi Fukui • C. Magbaily Fyle J. A. K. Kandawire • Carol P. MacCormack • Wyatt MacGaffey • Adolfo Mascarenhas • J.-C. Muller • Moriba Toure Sierra Leone, 1787-1987 Foreword • by the Vice-Chancellor, University of Sierra Leone 407 Introduction 408 History and politics 1787-1887-1987: reflections on a Sierra Leone bicentenary • Christopher Fyfe 411 The dissolution of Freetown City Council in 1926: a negative example of political apprenticeship in colonial Sierra Leone • AkintolaJ. G. Wyse 422 Women in Freetown politics, 1914-61: a preliminary study • LaRayDenzer 439 Ecology and technology The socio-ecology of firewood and charcoal on the Freetown peninsula • R. Akindele Cline^Cole 457 Culture, technology and policy in the informal sector: attention to endogenous development • C. Magbaily Fyle 498 Photography in Sierra Leone, 1850-1918 • Vera Viditz-Ward 510 Culture and language The national languages of Sierra Leone: a decade of policy experimentation • JokoSengova 519 Journal of the International African Institute Revue de l'lnstitut Africain International Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary material BMJ Global Health Supplementary Table 1: Focus Terms Health promotion topic “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” OR “AIDS” OR “asthma*” OR “breast feeding” OR “blood pressure” OR “bronchitis” OR “cancer” OR “cardiovascular disease” OR “child health” OR “cholera” OR “chronic kidney disease” OR “chronic lung disease” OR “COPD” OR “Diabet*” OR “HIV” OR “human immunodeficiency virus” OR “heart disease” OR “hypertension” OR “immune*” OR “infant health” OR “iodine” OR “leprosy” OR “malari*” OR “maternal health” OR “NCD” OR “non- communicable disease*” OR “nutrition” OR “polio” OR “pneumonia” OR “rehydration” OR “respiratory disease” OR “sex*” OR “schistosomiasis” OR “smallpox” OR “stroke” OR “syphilis” OR “TB” OR “tetanus” OR “trachoma” OR “tuberculosis” OR “vaccination” OR “vitamin” OR “zoono*” AND Arts and practices “artisan” OR “carving” OR “ceramic” OR “collage” OR “comedy” OR “comic” OR “cultur*” OR “danc*” OR “digital” OR “drama” OR “draw*” OR “film” OR “folk media” OR “game*” OR “literature” OR “music” OR “paint*” OR “photog*” OR “play” OR “poem” OR “poet*” OR “poster*” OR “pottery” OR “sing” OR “song” OR “story” OR “theatre” OR “writing” AND Location “Abyssinia “ OR “Africa” OR “Sub-Saharan Africa” OR “Angola” OR “Bechuanaland” OR “Benin” OR “Botswana” OR “British Central Africa” OR “Burkina Faso” OR “Burundi” OR “Cabo Verde” OR “Cameroon” OR “Cape Verde” OR “Central African Republic” OR “Chad” OR “Comoros” OR “Costa da Pimentia (Pepper Coast)” OR “Dahomey” OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR “Djibouti” OR