Project Report by Alex Bulmer Project Title: Blind Travel Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book a Sense of the World : How a Blind Man Became Historys

A SENSE OF THE WORLD : HOW A BLIND MAN BECAME HISTORYS GREATEST TRAVELER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jason Roberts | 379 pages | 01 Jun 2007 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007161263 | English | London, United Kingdom A Sense of the World : How a Blind Man Became Historys Greatest Traveler PDF Book Holman had a loose idea of his circumnavigation route: spend winter in western Russia, traverse Siberia the following spring, pass through Mongolia, sneak into China, hop on a whaling ship set for Hawaii, and improvise onward. Raised near an apothecary in Exeter, England, Holman enjoyed a healthy childhood and enlisted with the Royal Navy at age Holman was a hurricane of audacity, goodwill, and charm. Holman asked who would pay for the wheezing animal. Stock photo. Add links. Holman's charm and cunning nets him excursions to the Americas, Africa and the Orient - hunting slave A chance encounter in a library led the author to discover James Holman — In Nice, he harvested grapes on a vineyard estate. It entered into my heart, and I could have wept, not that I did not see, but that I could not portray all that I felt. He was famous in his day as "the Blind Traveler," but slipped into obscurity after his death in I have shared the joy and surprise of finding sounds, languages, twilights, cities, gardens and people, all of them distinctly different and unique p. He visited art museums, toured cathedrals, and hiked mountains. I can't fault the author's choice of subject, nor his research, nor his writing skills per se he's an accomplished journalist and graceful storyteller. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

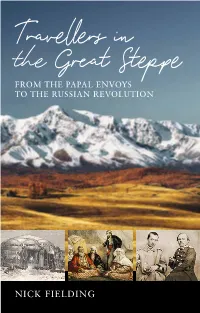

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

The Holmans in America : Concerning the Descendants of Solaman

yiij;iljiilil;:,ii]l,iili;iyillil!lllll , Gc 3 1833 01363 3596 929.2 I H731h v.l 1129678 REYNOLDS HISTORICAL GENEALOGY COLLECTION THE HOLMANS IN AMERICA VOLUME ONE 1 THE HOLMANS IN AMERICA CONCERNING THE DESCENDANTS OF SOLAMAN HOLMAN WHO SETTLED IN WEST NEWBURY, MASSACHUSETTS, IN 1692-3, ONE OF WHOM IS WILLIAM HOWARD' TAFT, THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES. INCLUDING A PAGE OF THE OTHER LINES OF HOLMANS IN AMERICA, WITH NOTES AND ANECDOTES OF THOSE OF THE NAME IN OTHER COUNTRIES. DAVID EMORY HOLMAN, M. D. or Attlebobo, MASSACHnsiTTS, U. S. A. VOLUME ONE THE GRAFTON PRESS GENEALOGICAL PUBLISHERS NEW YORK Copyright, 1909, By DAVID EMORY HOLMAN — 1129678 To My Deaelt Beloved Brother FRANK HOLMAN who has aided me always by his high artistic ideals and rare memory, and by his great interest in the work and de- sire that it should not be commonplace —and to the noble and generous mem- bees of the family, who have given of their time and thought to make this record of our race more complete This Volume Is Most Sincerely Dedicated ABBREVIATIONS adm Administration g. s Grave Stone bap Baptized int Intention of Marriage, or b Born Interred B. G Burying Ground m Married ch Children m. n. (m. n.) . .Maiden Name c. r Church Record P Page dau Daughter prob. ( prob. ) . Probate, or probably d Died ref Reference d. y Died Young s Son of f Form unm Unmarried fam. b Family Bible V. s Vital Statistics f . r Family Record CONTENTS PAOE Preface xi Introduction xiii Origin of the Name xv Camdens (England) Society Publications xvi " " Lieut. -

Class of 2021

THE UNIVERSITY of MISSISSIPPI One Hundred Sixty-Eighth COMMENCEMENT Saturday, the First of May 2021 THE UNIVERSITY of MISSISSIPPI TM One Hundred Sixty-Eighth COMMENCEMENT Saturday, the First of May 2021 Office of the Chancellor On behalf of the faculty and staff of the University of Mississippi, we extend a sincere welcome to the students, parents, families and friends gathered to celebrate the university’s 168th Commencement. We are pleased to recognize the spirit of our community and honor the academic accomplishments and dedication of our beloved candidates for graduation of the Class of 2021. Commencement is a time-honored tradition that recognizes the outstanding work and achievements of students and faculty. It is an exciting time for us, and we know this is a special occasion for all of you. Our students are the heart and soul of Ole Miss, and we take pride and inspiration in their accomplishments and growth. Today’s ceremony celebrates years of study, hard work and careful preparation, and we’re grateful that you have come to show your support, love and belief in these graduates. The members of the Class of 2021 accomplished so much during their time as Ole Miss students — they pursued their passions, maximized their potential and pushed their boundaries through outstanding learning opportunities and life-changing experiences. In addition, they endured the disruption caused by the pandemic, which has taught us all important life lessons about resilience and the need to be adaptable. Now, we can’t wait to see how they’ll build and grow personal legacies of achievement, service and leadership. -

Type 'In Confidence'

Historical scientific research on disability at the Royal Society “Travelling blind”, James Holman FRS (1785/6-1857) Scientists are fascinated by observing the world and this is one of the fundamental tools of the scientific method. Unsurprisingly, many have travelled the globe and written about it in both scientific and popular accounts. Cook’s Endeavour voyage and Charles Darwin’s journey of discovery aboard HMS Beagle resulted in some of the most famous examples of this kind of genre writing. But one of the most remarkable travelling-author Fellows of the Royal Society was not sighted: James Holman (1785/6-1857) who became celebrated and known to his contemporaries as ‘the blind traveller’. James Holman by R Cooper after Madame Fabroni, 1825/The Royal Society Holman was an Oxford-educated Royal Navy lieutenant serving aboard ship until 1807 when ill-health meant that he was invalided out of his maritime profession. The nature of his condition is not known, but Holman had some apparent difficulties in physical mobility and became completely blind at around twenty-four years of age. He refused a quiet retirement in Windsor in favour of restless journeying: “the desire of locomotion has to him become a new sense – a compensating principle...”. Holman travelled to Europe initially but would eventually circumnavigate the world, writing popular books about his experiences and impressions. James Holman by Edward Francis Finden after Thomas Charles Wageman, c.1834/The Royal Society credit Engraved by Edward Francis Finden (1791-1857) British printmaker after Thomas Charles Wageman (1787-1853) English artist Later biographical accounts of Lieutenant Holman have tended to concentrate on the novelty of his situation as a solo adventurer and on the more arduous aspects of his journeying. -

O VIAJANTE CEGO JAMES HOLMAN E OS LIMITES DO OLHAR VIAJANTE Revista De História, Núm

Revista de História ISSN: 0034-8309 [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo Brasil Torrão Filho, Amilcar DOES EVERY TRAVELLER SEE ALL THAT HE DESCRIBES? ” O VIAJANTE CEGO JAMES HOLMAN E OS LIMITES DO OLHAR VIAJANTE Revista de História, núm. 175, julio-diciembre, 2016, pp. 319-348 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=285049446012 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto rev. hist. (São Paulo), n. 175, p. 319-348, jul.dez., 2016 Amilcar Torrão Filho http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9141.rh.2016.115230 “Does every traveller see all that he describes?” O viajante cego James Holman e os limites do olhar viajante “DOES EVERY TRAVELLER SEE ALL THAT HE DESCRIBES?” O VIAJANTE CEGO JAMES HOLMAN E OS LIMITES DO OLHAR VIAJANTE* Contato Amilcar Torrão Filho** Rua Monte Alegre, 984 – Perdizes 05014-901 – São Paulo – SP Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo [email protected] São Paulo – São Paulo – Brasil Resumo Olhar etnográfico, olhar pitoresco, olhar ilustrado, olhar evangelizador, olhar imperialista: o olhar é una metáfora frequente nas descrições e análises da li- teratura de viagem em suas mais diversas manifestações. Ver bem tem como consequência uma melhor compreensão do lugar visitado, o que pode converter o viajante em um especialista do lugar visitado, alguém que pode construir um texto de autoridade sobre determinado espaço, propor projetos políticos de rege- neração, colonização, evangelização. -

Download Issue

MAN AND THE OCEANS THE CAUSES OF WARS by Michael Howard INVENTING TRADITION COOUNG THE SOUTH WALLACE STEVENS Pertodicds / Books WILSON COLUMBIA THE COLUMBIA BOOK OF THE ANDEAN PAST CHINESE POETRY LAND,SOCIETIES, AND CONFLICTS FROM EARLY TIMES TO THE Magnus Morner. The first comprehensive THIRTEENTH CENTURY history of the area that once comprised the Inca Translated and Edited by Burton Watson. "An Empire and today consists of Bolivia, Ecuador, invaluable body of renderings from the vast and Peru. Explores the way in which man adapted to the awsome Andean environment. tradition of Chinese poetry.. .The presentation of.. [Watson's] assembled translations, drawn Illus. 320 pp., $25.00 (September) from decades of work, is an event to celebrate."-W.S. Merwin.Trans1ations from the INTERNATIONAL STUDIES AND Oriental Classics. 352 pp., $19.95 (August) ACADEMIC ENTERPRISE A CHAPTER IN THE ENCLOSURE OF UNDERSTANDING IMPERIAL AMERICAN LEARNING RUSSIA Robert A. McCaughey, A critical account of the Marc Raeff: Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. historical process by which the scholarly study I was delighted to read this book, which I found by Americans of the outside world, from the interesting, provocative, and informative."- early nineteenth century on, became essentially Richard Wortrnan, Princeton University. 240 pp., an academic enterprise. 312 pp., $28.00 $19.95 (June) GOVERNOR REAGAN, "THE GOVERNMENT OF GOD" GOVERNOR BROWN IRAN'S ISLAMIC REPUBLIC A SOCIOLOGY OF EXECUTIVE POWER Cheryl Benard andzalmay Khalilzad. This is the Gary G. Hamilton and Nicole W Biggart. Based first disciplined study of Iran's turbulent recent on interviews with more than 100 participants history. -

Western Africa

Western Africa Catalogue 100 London: Michael Graves-Johnston, 2010 Michael Graves-Johnston 54, Stockwell Park Road, LONDON SW9 0DA Tel: 020 - 7274 – 2069 Fax: 020 - 7738 – 3747 Website: www.Graves-Johnston.com Email: [email protected] Western Africa: Catalogue 100. Published by Michael Graves-Johnston, London: 2010. VAT Reg.No. GB 238 2333 72 ISBN 978-0-9554227-3-7 Price: £ 10.00 All goods remain the property of the seller until paid for in full. All prices are net and forwarding is extra. All books are in very good condition, in the publishers’ original cloth binding, and are First Editions, unless specifically stated otherwise. Any book may be returned if unsatisfactory, provided we are advised in advance. Your attention is drawn to your rights as a consumer under the Consumer Protection (Distance Selling) Regulations 2000. All descriptions in this catalogue were correct at the time of cataloguing. Western Africa 1. ABADIE, Maurice. La Colonie du Niger: Afrique Centrale. Préface de M. le Governeur Maurice Delafosse. Paris: Société d’Éditions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales, 1927 Recent cloth with original wrappers bound-in, 4to. 466pp. 47 collotype plates, coloured folding map, biblio., index. A very nice copy in a recent dark-blue buckram with leather label to spine. Maurice Abadie (1877-1948) was a lieutenant-colonel in the French Colonial Infantry when he wrote this. He later wrote on tribal life in Vietnam and became a general in the French army. £ 150.00 2. ADANSON, M. A Voyage to Senegal, The Isle of Goree, and the River Gambia. By M. -

The Case of Kru Workers, 1792-1900 Jeffrey

HOMELAND, DIASPORAS AND LABOUR NETWORKS: THE CASE OF KRU WORKERS, 1792-1900 JEFFREY GUNN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO May 2019 JEFFREY GUNN, 2019 ii Abstract By the late eighteenth century, the ever-increasing British need for local labour in West Africa based on malarial, climatic, and manpower concerns led to a willingness of the British and Kru to experiment with free wage labour contracts. The Kru’s familiarity with European trade on the Kru Coast (modern Liberia) from at least the sixteenth century played a fundamental role in their decision to expand their wage earning opportunities under contract with the British. The establishment of Freetown in 1792 enabled the Kru to engage in systematized work for British merchants, ship captains, and British naval officers. Kru workers increased their migration to Freetown establishing what appears to be their first permanent labouring community beyond their homeland on the Kru Coast. Their community in Freetown known as Kroo Town (later Krutown) ensured their regular employment on board British commercial ships and Royal Navy vessels circumnavigating the Atlantic and beyond. In the process, the Kru established a network of Krutowns and community settlements in many Atlantic ports including Fernando Po, Ascension Island, and the Cape of Good Hope, and in the British Caribbean in British Guiana and Trinidad. This dissertation structures the fragmented history of Kru workers into a coherent framework. In this study, I argue that the migration of Kru workers in the Atlantic, and even to the Indian and Pacific Oceans, represents a movement of free wage labour that transformed the Kru Coast into a homeland that nurtured diasporas and staffed a vast network of workplaces. -

Ontario County Men

COUNTY OF ONTARIO PA SHORT NOTES AS TO THE EARLY SETTLEMENT AND PROGRESS OF THE COUNTY AND BRIEF REFERENCES TO THE Pioneers and Some Ontario County Men WHO HAVE TAKEN A PROMINENT PART IN PROVINCIAL AND DOMINION AFFAIRS —BY— J, E. FAREWELL, LL.B., K, G., County Clerk and Solicitor. WHITBY: GAZETTE-CHRONICLE PRESS 1907. The following rough sketches relating to the history of the County were prepared at the request of the County Council. For much of the information the writer is indebted to notes kindly furnished by Municipal Clerks. As to the Township of Reach reference has been frequently made to a pamphlet written many years ago by the Rev. Mr. Monteith and first published in "The North Ontario Observer" and to the late W. H. Higgins' "Work on the Life and Times of Joseph Gould." The sketch of Oshawa was written principally by Dr. T. E. Kaiser, its present Mayor. It will doubtless be claimed that many of the incidents contained herein are incorrect as to names and dates. The writer is aware that in several instances such different statements have appeared in print. He has given them according to the best information obtainable. He regrets that he had not more space at his disposal and trusts that imperfect as these notes are they will cause others who have the time and means to give their attention to the important matter of collecting materials for a County History, and that steps will speedily be taken to establish a County Historical Society to continue the work. COUNTY OF ONTARIO. -

The Blind Traveler One Might

The Blind Traveler One might ask “Why should we care about a blind British traveler? I suppose he went on Trips. But, did he have anything to do with Dartmouth?” OK, these are good questions. On the other hand, maybe we should observe that this gentleman might have actually been something on the order of The Second Coming of John Ledyard! James Holman (1786 – 1857), known as the "Blind Traveler," was a British adventurer, author and social observer, best known for his writings on his extensive travels. Completely blind and suffering from debilitating pain and limited mobility, he undertook a series of solo journeys that were unprecedented both in their extent of geography and method of "human echolocation." In 1866, the journalist William Jerdan wrote that "From Marco Polo to Mungo Park, no three of the most famous travelers, grouped together, would exceed the extent and variety of countries traversed by our blind countryman." In 1832, Holman became the first blind person to circumnavigate the globe. He continued traveling, and by October 1846 had visited every inhabited continent. John Ledyard, of course, had traveled extensively by sea or by foot, alone or with others, and was thought to have seen more of the world than any other person ever had by the end of the 18th Century. Holman was born in Exeter, the son of an apothecary. Like John Ledyard, he entered the British Royal Navy, as a first-class volunteer in 1798, and was appointed lieutenant in 1807. In 1810, while on the Guerriere off the coast of the Americas, he suffered an illness that first afflicted his joints, then finally his vision.