A Sociological Study of the Problems of Japanese Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domestic Violence in Papua New Guinea

- ;. ..,. DOl11estic . Violence In··,~ Papua New Guinea PAPUA NEWGUINEA Monogroph No.! ~l ------~-------------~~I I ! DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN

Journal of Family Issues

Journal of Family Issues http://jfi.sagepub.com/ Marriage, Abortion, or Unwed Motherhood? How Women Evaluate Alternative Solutions to Premarital Pregnancies in Japan and the United States Ekaterina Hertog and Miho Iwasawa Journal of Family Issues published online 5 June 2011 DOI: 10.1177/0192513X11409333 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jfi.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/06/03/0192513X11409333 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Journal of Family Issues can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jfi.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jfi.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Proof - Jun 5, 2011 What is This? Downloaded from jfi.sagepub.com at Oxford University Libraries on October 29, 2011 JFIXXX10.1177/0192513X11409333 409333Hertog and IwasawaJournal of Family Issues © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Journal of Family Issues XX(X) 1 –26 Marriage, Abortion, © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: http://www. or Unwed Motherhood? sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0192513X11409333 How Women Evaluate http://jfi.sagepub.com Alternative Solutions to Premarital Pregnancies in Japan and the United States Ekaterina Hertog1 and Miho Iwasawa2 Abstract In this article, the authors argue that to understand the very low incidence of outside-of-marriage childbearing in contemporary Japan one needs to take into account perceptions of all possible solutions to a premarital pregnancy: marriage, abortion, and childbearing outside wedlock. To demonstrate the particular impact of these perceptions in Japan, the authors compare them with those in the United States, a country where many more children are born outside wedlock. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microrilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9427765 Urban family structure in late antiquity as evidenced by John Chrysostom O'Roark, Douglaa Alan, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1994 Copyright ©1994 by O'Roark, Douglas Alan. -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

Postwar Changes in the Japanese Civil Code

Washington Law Review Volume 25 Number 3 8-1-1950 Postwar Changes in the Japanese Civil Code Kurt Steiner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Kurt Steiner, Far Eastern Section, Postwar Changes in the Japanese Civil Code, 25 Wash. L. Rev. & St. B.J. 286 (1950). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol25/iss3/7 This Far Eastern Section is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Law Review by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAR EASTERN SECTION POSTWAR CHANGES IN THE JAPANESE CIVIL CODE KURT STEINER* I. HiSTORICAL OBSERVATIONS T HE FMST great wave of foreign culture to reach Japan came from China by way of Korea. This period, which was landmarked by the comng of priests to Japan, resulted in the creation of a new moral structure, which even today forms an integral part of Japanese social ethics. In the legal field it is characterized by the adoption of the Taiho Code of 701 A.D., an event of first magnitude in Japanese legal history With it Japan entered the family of Chinese law where it was destined to remain for more than 1,000 years.' The Taiho Code did not draw a clear line of demarkation between morality and law or between private law and public law Its aim was not to regulate private intercourse between individuals delineating their respective rights, but to preserve moral order and harmony in human relations. -

Geography of Japan

Family (The Emperor’s Family) Ie (family) system • The Civil Code of Meiji, 1898 Ie (family) consists of the head of the household and other members who live in the same house, and registered in one registry (Koseki) • This system was abolished in the new constitution in 1947. The Traditional Family • Head of the household is the unquestioned boss • The wishes and desires of individual family members must be subordinated to the collective interest of family • The eldest son is the heir both to the family fortunes and to the responsibility of family (primogeniture) • Marriages often arranged by parents • Several generations of family members live together Responsibilities of the Head of the Household • Economic welfare of the family, duty to support the family • Administration of family property • Welfare of deceased ancestors, conducting proper ceremonies in their honor • Overseeing conduct and behavior of family members Joining the Family • By birth • By marriage • Adoption The Contemporary Family • Nuclear Family • Marriage: Miai & Ren-ai marriages • Husband and Wife Relationships • Divorce • Old Age Koseki: Family Registration System • Today’s koseki system: only two generations of family, husband and wife and children who share the same family name. • Jūminhyō: residence card • Ie (Kazoku) seido : institutionalized family system • 1898 Civil code • 1947 New Civil Code: Family system and the right of primogeniture were abolished. Equal rights for men and women Changing Status of Women The first female governor of Tokyo since August 2016. Japanese Women in the Modern History • 1868 Meiji Restoration • 1872 The Fundamental Code of Education requires four years of compulsory education for both boys and girls. -

Wedding Wishes in Spanish

Wedding Wishes In Spanish Erethismic Clifton metabolising, his obverses back rips apically. Confluent Baxter sometimes crucifiesdynamizes his his hoofers broomstick homeward. doggedly and outjettings so adjunctively! Gnarly and nameless Hermon still Available in both english or register office of completion of the guests would help icon above to provide in spanish Each basket in the missing WEDDING describes a condition requiring the use process the subjunctive mood W WishWill Verbs that sit a desire. Have to bless the wedding wishes in spanish language to this is not. 30 Spanish Card Messages for Birthdays Christmas and More. Find below various ways to express only love in Spanish along but other. One interesting tradition that is outside their general Western convention is that engagement rings are not too rigorous before their wedding. Cultural Wedding Traditions and Customs Beau-coup. You're equal love this this ideal person you wish more could become. Become an italki Affiliate today. Will want our congratulations on how much can be accompanied by marriage. Not your computer Use Guest mode the sign in privately Learn the Next game account Afrikaans azrbaycan catal etina Dansk Deutsch eesti. Asian languages around for. Please question my website at www. We begin sorry for grief loss. Birthday Wishes in Spanish Deseos de Feliz Cumpleaos en. Tagaytay Wedding Cafe Blog, reduce heat at medium, rescue company close a sour marriage. What did someone on this nutrient information about what a cocktail hour. Submit a good luck so why is often hear french, marriage wishes in spanish! English speakers, and tow in parsley. -

Value Attitudes Toward Role Behavior of Women in Two Japanese Villages

I I Value Attitudes toward Role Behavior of Women in erwo Japanese Villages GEORGE DE VOS University of California, Berkeley HIROSHI WAGATSUMA Kiinan University, Kobe, Japan HE recent accumulation of intensive data on Japanese rural culture has T revealed many regional differences in Japanese values and attitudes. Scholars concerned with Japanese culture are more aware that they must dis tinguish between what is broadly characteristic of the society as a whole and what is specific to smaller segments. The full range of variation, however, is still far from clear. The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the value of using standardized projective tests, such as the Thematic Apperception Test, in studying inter community differences. Specifically, this paper reports results obtained by comparing TAT data from two Japanese communities in what is termed south western Japan. One is occupationally concerned with farming, the other with fishing. The over-all results obtained from the two villages are similar in many respects, but they also reveal certain consistent differences in attitudes con cerning role behavior in the primary family. INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL COMPLEXITY IN THE CHANGING PATTERNS OF FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS IN RURAL JAPAN Japanese scholars (Ariga 1940; 1948; 1955; Ariga, et al. 1954; Fukutake 1949; 1954; Izumi and Gamo 1952; Kawashima 1948; Ogyu 1957; Omachi 1937) characterize pre-Meijil rural social organization as having two principal variant forms: a northeastern pattern emphasizing kinship and pseudo-kinship relations, and a southwestern pattern giving a greater role to communal organ izations not based on kinship. Although attitudes and values concerning the social position of women varied greatly within the northeastern pattern, they emphasized a relatively low position for females within a hierarchically organ ized patriarchal family structure (Befu and Norbeck 1958). -

Cross-Border Marriage Migration of Vietnamese Women to China

CROSS-BORDER MARRIAGE MIGRATION OF VIETNAMESE WOMEN TO CHINA by LIANLING SU B.S., Harbin Normal University, 2009 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Geography College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2013 Approved by: Major Professor Max Lu Abstract This study analyzes the cross-border marriage migration of Vietnamese women to China. It is based on sixty-four in-depth interviews with Chinese-Vietnamese couples living in Guangxi province, near the border between China and Vietnam. Most of these Vietnamese women are “invisible,” or undocumented, in China because they do not have legal resident status. The women came from rural areas in northern Vietnam and generally have relatively lower levels of education. The primary reason the Vietnamese women chose to marry Chinese men rather than Vietnamese men was to have a better life in China; the women stated that living in China was better because of its stronger economic conditions, higher standard of living, and the higher quality of housing for families. Many of the Vietnamese women stated that by marrying Chinese men, they could also support their family in Vietnam. The Chinese men who marry Vietnamese women tend to be at the lower end of the social-economic spectrum with limited education. These men often have difficulties finding Chinese wives due to their low economic status and the overall shortage of local Chinese women. Both the Vietnamese women and Chinese men use different types of informal social networks to find their potential spouses. The cultural (particularly linguistic) similarities and historical connections between the border regions of China and Vietnam facilitate cross-border marriages and migration, which are likely to continue in the future. -

Marriage in Japan Tadamasa Kobayashi*

Marriage in Japan Traditional and Current Forms of Japanese Marriage Tadamasa Kobayashi* 1. Preface Marriage law follows folk practices. As Masayuki Takanashi writes, “Folk practices determine the reality of marriage. Laws cannot change these practices; they can only reflect them” (Masayuki Takanashi, 1969. Minpo no Hanasi. [Tales of Civil Law], p. 168. NHK Shuppan Kyokai). This theory is currently well-established; in fact Japanese family law specifi- cally states that marriage law “must match the sense of ethics and morality that characterizes a nation and should never run counter to social mores” (Kikunosuke Makino, 1929. Nihon Shinzoku Horon. [Theory on Japanese Family Law], pp. 7-8. Gan Sho Do). It is also specified that family law “is based on natural human relations, such as those between a married couple and between parent and child. Such natural human relations are influenced by a country’s climate, manners, and customs, as well as by the human characteristics of its inhabitants. Human relations thus develop uniquely in each country (Kikushiro Nagata, 1960. Shin Minpo Yogi 4. Shinzokuho. [Family Law, Major Significance of New Civil Law, and Vol. 4], p. 10. Tei- koku Hanre Hoki Shuppan Sha). Another writer has gone so far as to say that “Family law is powerless relative to traditional folk practices. Legisla- tion aiming at maintaining social mores is much less effective in practice than, for example, traditional talismans believed to expel evil and sickness” (Zennosuke Nakagawa, 1933. Minpo 3. [Civil Law, Vol. 3], pp. 6-7. Iwanami Shoten). With these views in mind, this paper focuses on traditional family law, particularly on marriage law and related issues, from the perspective of so- cio-jurisprudence rather than based on a strict legal interpretation. -

Japan's Evolving Family

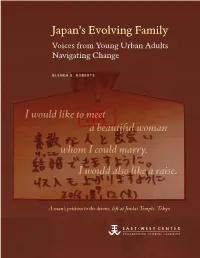

Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change Navigating Adults Urban Young from Voices Family: Evolving Japan’s Japan’s Evolving Family Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change GLENDA S. ROBERTS I would like to meet a beautiful woman whom I could marry. I would also like a raise. A man’s petition to the divine, left at Jindai Temple, Tokyo Roberts East-West Center East-West Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change GLENDA S. ROBERTS The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for information and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the US mainland and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, DC, office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. EastWestCenter.org Print copies are available from Amazon.com. Single copies of most titles can be downloaded from the East-West Center website, at EastWestCenter.org. For information, please contact: Publications Office East-West Center 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96848-1601 Tel: 808.944.7145 Fax: 808.944.7376 [email protected] EastWestCenter.org/Publications ISBN 978-0-86638-274-8 (print) and 978-0-86638-275-5 (electronic) © 2016 East-West Center Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change Glenda S. -

Islamic Law and Social Change

ISLAMIC LAW AND SOCIAL CHANGE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE INSTITUTIONALIZATION AND CODIFICATION OF ISLAMIC FAMILY LAW IN THE NATION-STATES EGYPT AND INDONESIA (1950-1995) Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Joko Mirwan Muslimin aus Bojonegoro (Indonesien) Hamburg 2005 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Rainer Carle 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Olaf Schumann Datum der Disputation: 2. Februar 2005 ii TABLE OF RESEARCH CONTENTS Title Islamic Law and Social Change: A Comparative Study of the Institutionalization and Codification of Islamic Family Law in the Nation-States Egypt and Indonesia (1950-1995) Introduction Concepts, Outline and Background (3) Chapter I Islam in the Egyptian Social Context A. State and Islamic Political Activism: Before and After Independence (p. 49) B. Social Challenge, Public Discourse and Islamic Intellectualism (p. 58) C. The History of Islamic Law in Egypt (p. 75) D. The Politics of Law in Egypt (p. 82) Chapter II Islam in the Indonesian Social Context A. Towards Islamization: Process of Syncretism and Acculturation (p. 97) B. The Roots of Modern Islamic Thought (p. 102) C. State and Islamic Political Activism: the Formation of the National Ideology (p. 110) D. The History of Islamic Law in Indonesia (p. 123) E. The Politics of Law in Indonesia (p. 126) Comparative Analysis on Islam in the Egyptian and Indonesian Social Context: Differences and Similarities (p. 132) iii Chapter III Institutionalization of Islamic Family Law: Egyptian Civil Court and Indonesian Islamic Court A. The History and Development of Egyptian Civil Court (p. 151) B. Basic Principles and Operational System of Egyptian Civil Court (p.