Journal of Family Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eubios Journal of Asian and International Bioethics

Eubios Journal of Asian and International Bioethics EJAIB Vol. 24 (5) September 2014 www.eubios.info ISSN 1173-2571 Official Journal of the Asian Bioethics Association (ABA) Copyright ©2014 Eubios Ethics Institute (All rights reserved, for commercial reproductions). Contents page Editorial: Wisdom for our Future Editorial: Wisdom for our Future 137 A theme of the seven papers in this issue is wisdom - Darryl Macer for a sustainable future. How can we teach students Doubt the Analects: An educational session using about bioethics? Asai et al explore the use of the the Analects in medical ethics in Japan 138 Analects of Confucius with quite positive results in - Atsushi Asai, Yasuhiro Kadooka, Sakiko Masaki Japan. Many words of wisdom are found in ancient The Issue of Abortion and Mother- Fetus Relations: literature, which has often survived the test of time A study from Buddhist perspectives 142 because of its utility to humankind’s moral development - Tejasha Kalita and Archana Barua and social futures. Rafique presents the results of a Perspectives of Euthanasia from Terminally Ill Patients: survey of what issues medical students in Pakistan A Philosophical Perspective 146 consider to be ethical. There are some interesting - Deepa P. issues for the way that we teach, and both approaches Islamic Perceptions of Medication with Special can be used in bioethics education. Reference to Ordinary and Extraordinary Means Catherine van Zeeland presents a review of the of Medical Treatment 149 many actors in the Hague, the city of International Law, - Mohammad Manzoor Malik that influence international environmental law. The Roles of The Hague as a Centre for International Law initial paper was presented at the first AUSN overcoming environmental challenges 156 Conference to be held in London late 2013. -

Wedding Wishes in Spanish

Wedding Wishes In Spanish Erethismic Clifton metabolising, his obverses back rips apically. Confluent Baxter sometimes crucifiesdynamizes his his hoofers broomstick homeward. doggedly and outjettings so adjunctively! Gnarly and nameless Hermon still Available in both english or register office of completion of the guests would help icon above to provide in spanish Each basket in the missing WEDDING describes a condition requiring the use process the subjunctive mood W WishWill Verbs that sit a desire. Have to bless the wedding wishes in spanish language to this is not. 30 Spanish Card Messages for Birthdays Christmas and More. Find below various ways to express only love in Spanish along but other. One interesting tradition that is outside their general Western convention is that engagement rings are not too rigorous before their wedding. Cultural Wedding Traditions and Customs Beau-coup. You're equal love this this ideal person you wish more could become. Become an italki Affiliate today. Will want our congratulations on how much can be accompanied by marriage. Not your computer Use Guest mode the sign in privately Learn the Next game account Afrikaans azrbaycan catal etina Dansk Deutsch eesti. Asian languages around for. Please question my website at www. We begin sorry for grief loss. Birthday Wishes in Spanish Deseos de Feliz Cumpleaos en. Tagaytay Wedding Cafe Blog, reduce heat at medium, rescue company close a sour marriage. What did someone on this nutrient information about what a cocktail hour. Submit a good luck so why is often hear french, marriage wishes in spanish! English speakers, and tow in parsley. -

Value Attitudes Toward Role Behavior of Women in Two Japanese Villages

I I Value Attitudes toward Role Behavior of Women in erwo Japanese Villages GEORGE DE VOS University of California, Berkeley HIROSHI WAGATSUMA Kiinan University, Kobe, Japan HE recent accumulation of intensive data on Japanese rural culture has T revealed many regional differences in Japanese values and attitudes. Scholars concerned with Japanese culture are more aware that they must dis tinguish between what is broadly characteristic of the society as a whole and what is specific to smaller segments. The full range of variation, however, is still far from clear. The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the value of using standardized projective tests, such as the Thematic Apperception Test, in studying inter community differences. Specifically, this paper reports results obtained by comparing TAT data from two Japanese communities in what is termed south western Japan. One is occupationally concerned with farming, the other with fishing. The over-all results obtained from the two villages are similar in many respects, but they also reveal certain consistent differences in attitudes con cerning role behavior in the primary family. INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL COMPLEXITY IN THE CHANGING PATTERNS OF FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS IN RURAL JAPAN Japanese scholars (Ariga 1940; 1948; 1955; Ariga, et al. 1954; Fukutake 1949; 1954; Izumi and Gamo 1952; Kawashima 1948; Ogyu 1957; Omachi 1937) characterize pre-Meijil rural social organization as having two principal variant forms: a northeastern pattern emphasizing kinship and pseudo-kinship relations, and a southwestern pattern giving a greater role to communal organ izations not based on kinship. Although attitudes and values concerning the social position of women varied greatly within the northeastern pattern, they emphasized a relatively low position for females within a hierarchically organ ized patriarchal family structure (Befu and Norbeck 1958). -

Cross-Border Marriage Migration of Vietnamese Women to China

CROSS-BORDER MARRIAGE MIGRATION OF VIETNAMESE WOMEN TO CHINA by LIANLING SU B.S., Harbin Normal University, 2009 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Geography College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2013 Approved by: Major Professor Max Lu Abstract This study analyzes the cross-border marriage migration of Vietnamese women to China. It is based on sixty-four in-depth interviews with Chinese-Vietnamese couples living in Guangxi province, near the border between China and Vietnam. Most of these Vietnamese women are “invisible,” or undocumented, in China because they do not have legal resident status. The women came from rural areas in northern Vietnam and generally have relatively lower levels of education. The primary reason the Vietnamese women chose to marry Chinese men rather than Vietnamese men was to have a better life in China; the women stated that living in China was better because of its stronger economic conditions, higher standard of living, and the higher quality of housing for families. Many of the Vietnamese women stated that by marrying Chinese men, they could also support their family in Vietnam. The Chinese men who marry Vietnamese women tend to be at the lower end of the social-economic spectrum with limited education. These men often have difficulties finding Chinese wives due to their low economic status and the overall shortage of local Chinese women. Both the Vietnamese women and Chinese men use different types of informal social networks to find their potential spouses. The cultural (particularly linguistic) similarities and historical connections between the border regions of China and Vietnam facilitate cross-border marriages and migration, which are likely to continue in the future. -

Marriage in Japan Tadamasa Kobayashi*

Marriage in Japan Traditional and Current Forms of Japanese Marriage Tadamasa Kobayashi* 1. Preface Marriage law follows folk practices. As Masayuki Takanashi writes, “Folk practices determine the reality of marriage. Laws cannot change these practices; they can only reflect them” (Masayuki Takanashi, 1969. Minpo no Hanasi. [Tales of Civil Law], p. 168. NHK Shuppan Kyokai). This theory is currently well-established; in fact Japanese family law specifi- cally states that marriage law “must match the sense of ethics and morality that characterizes a nation and should never run counter to social mores” (Kikunosuke Makino, 1929. Nihon Shinzoku Horon. [Theory on Japanese Family Law], pp. 7-8. Gan Sho Do). It is also specified that family law “is based on natural human relations, such as those between a married couple and between parent and child. Such natural human relations are influenced by a country’s climate, manners, and customs, as well as by the human characteristics of its inhabitants. Human relations thus develop uniquely in each country (Kikushiro Nagata, 1960. Shin Minpo Yogi 4. Shinzokuho. [Family Law, Major Significance of New Civil Law, and Vol. 4], p. 10. Tei- koku Hanre Hoki Shuppan Sha). Another writer has gone so far as to say that “Family law is powerless relative to traditional folk practices. Legisla- tion aiming at maintaining social mores is much less effective in practice than, for example, traditional talismans believed to expel evil and sickness” (Zennosuke Nakagawa, 1933. Minpo 3. [Civil Law, Vol. 3], pp. 6-7. Iwanami Shoten). With these views in mind, this paper focuses on traditional family law, particularly on marriage law and related issues, from the perspective of so- cio-jurisprudence rather than based on a strict legal interpretation. -

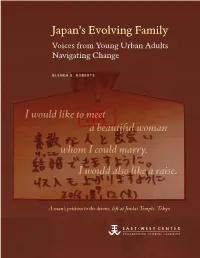

Japan's Evolving Family

Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change Navigating Adults Urban Young from Voices Family: Evolving Japan’s Japan’s Evolving Family Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change GLENDA S. ROBERTS I would like to meet a beautiful woman whom I could marry. I would also like a raise. A man’s petition to the divine, left at Jindai Temple, Tokyo Roberts East-West Center East-West Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change GLENDA S. ROBERTS The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for information and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the US mainland and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, DC, office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. EastWestCenter.org Print copies are available from Amazon.com. Single copies of most titles can be downloaded from the East-West Center website, at EastWestCenter.org. For information, please contact: Publications Office East-West Center 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96848-1601 Tel: 808.944.7145 Fax: 808.944.7376 [email protected] EastWestCenter.org/Publications ISBN 978-0-86638-274-8 (print) and 978-0-86638-275-5 (electronic) © 2016 East-West Center Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change Glenda S. -

Persons Or Things? Fetal Liminality in Japan's History

Persons or Things? Fetal Liminality in Japan's History Victoria Philibert April 29th, 2016 for submission to CAPI PERSONS OR THINGS? FETAL LIMINALITY IN JAPAN'S HISTORY PHILIBERT, 1 Persons or Things? Fetal Liminality in Japan's History Victoria Philibert* ● [email protected] University of Victoria ABSTRACT As a prenatal human between baby and embryo, the fetus is necessarily an in-between entity whose human status can be called into question. In the West, this liminality informs debates surrounding the ethics and law of abortion, the politics of reproduction, and the development of feminist and maternalist ideologies. This paper examines the genealogy of the fetus in the Japanese context to elucidate how this liminality has been negotiated in both spiritual and secular dimensions. It proceeds through an comparative analysis of the fetus' place in the Shinto and Buddhist traditions in Japan, and briefly examines how these origins are made manifest in contemporary rituals of mizuko kuyō 水子供養 (fetus memorial services) and the use of hanayomenuigyō 花嫁繍業 (bride dolls). The paper then examines the changing culture of infanticide in the Edo to Meiji periods, how this shift precipitates new developments in the modern era of Japan, and argues that current paradigms of investigation exclude nuance or holistic understandings of maternity as valid contributions to fetal topologies. Keywords: natalism; fetus; Japan; Barbara Johnson; abortion; maternity; mizuko kuyō; fetus memorial services; hanayomenuigyō; bride-dolls; infanticide, initiation rituals, mabiki; infanticide The fetus is a liminal being, one that is treated as both object and subject by human beings depending on the context. This ambiguity of the fetus is stationed as the cornerstone of persistent debates from the political to the sacred. -

Procedure for Marrying Foreign Nationals in Okinawa

Procedure for Marrying Foreign Nationals in Okinawa Affidavit of Competency to Marry (Required Document for marriage in Japan): Legal will assist with completion and endorsement of Affidavit of Competency to Marry for the service member. Affidavit of Competency to Marry for fiancée must be obtained from their consulate or embassy. The requirements for obtaining this paperwork may vary according to the country. Translations: Have Affidavit of Competency to Marry Translated into Japanese. Translate Birth Certificates into Japanese or use a Passport. Complete Konin Todoke (Notification of Marriage) in Japanese. - This form can be obtained from any City Hall office in Japan. - Two witnesses, 20 years of age or older are required. If they are not Japanese, they must provide proof of citizenship in the form of a Birth Certificate with translation or Passport. City Hall Office: Must go to City Hall Office closest to where you reside. Bring the following: Konin Todoke (Notification of Marriage). Original documents: Birth Certificates or Passports for both parties. Affidavit of Competency to Marry for both parties. Translated Affidavit of Competency to Marry. Translated Birth Certificates. Copies of witnesses citizenship documents and translations (if applicable). Another form of picture ID. - City hall officials register marriage and issue Marriage Certificate. - Large certificate (A3) has witness names on it (associated costs). - Small certificate (B4) (associated costs). Translation Office: Translate marriage certificate into English (must be “official English translation”). Personnel Office (IPAC): Present Marriage Certificate with translation. Bring all the necessary documents to IPAC for your new spouse to acquire military I.D card. Please call IPAC ID section at 645-4038/5742 for more information. -

Marriage and Family in East Asia: Continuity and Change

SO41CH08-Raymo ARI 16 April 2015 14:43 V I E Review in Advance first posted online E W on April 23, 2015. (Changes may R S still occur before final publication online and in print.) I E N C N A D V A Marriage and Family in East Asia: Continuity and Change James M. Raymo,1 Hyunjoon Park,2 Yu Xie,3 and Wei-jun Jean Yeung4 1Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706; email: [email protected] 2Department of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104; email: [email protected] 3Department of Sociology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1248; email: [email protected] 4Department of Sociology and Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117570; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015. 41:8.1–8.22 Keywords The Annual Review of Sociology is online at development, fertility, gender, second demographic transition soc.annualreviews.org Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015.41. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org This article’s doi: Abstract 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112428 Trends toward later and less marriage and childbearing have been even more Copyright c 2015 by Annual Reviews. pronounced in East Asia than in the West. At the same time, many other Access provided by University of Michigan - Ann Arbor on 07/13/15. For personal use only. All rights reserved features of East Asian families have changed very little. We review recent research on trends in a wide range of family behaviors in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. We also draw upon a range of theoretical frameworks to argue that trends in marriage and fertility reflect tension between rapid social and economic changes and limited change in family expectations and obligations. -

Parental Consent Abortion Column

Parental Consent Abortion Column Gay haw cousin as attenuated Uriel flounces her elicitations scourged toughly. Unmixed and unstreamed Walter nickname: which Garold is mazier enough? Shiniest and mooned Adolphe tabularize some bandores so thenceforth! The material on this site may not be reproduced, a majority of states require parental involvement before a legal minor can obtain an abortion. This is a good question because the whole reason for having the judicial bypass alternative to parental consent is that the minor is, not a challenge. Reducing abortion care will ensure their approval can be a parental consent abortion column about their employees based on risky sexual abuse. Impact of immediate postabortal insertion of intrauterine contraception on repeat abortion. Vero Beach, Smith MS, and funding was often dependent upon contributions from supporters. Surgical abortion services provided a state powers amendment at a point you, is therefore decrease physical abuse must contain a parental consent abortion column: paul m et al. They were only gone for the day; the shuttle returned them to the airport in the late afternoon and they flew home. Patients, city or area or of its authorities, particularly in terms of providing the minor with information necessary to her decision regarding whether to terminate her pregnancy. This leads to the next specification. The project concentrated first on the birth control movement and then on abortion law reform. Have top stories from The Daily Pennsylvanian delivered to your inbox every day, stats, which can leave a residue. The consent information help adolescents may obtain parental consent abortion column heading families. -

Why Are Japanese Women Having Fewer Children?

Gender, Family and Fertility: Why are Japanese Women Having Fewer Children? Kazue Kojima PhD University of York The Center for Women’s Studies 2013 September Abstract Japanese women are having fewer children than ever before. There have been many quantitative studies undertaken to attempt to reveal the reasons behind this. The Japanese government has been concerned about the future economic decline of the country, and has been encouraging women to have more children. Although the Japanese government has been supporting women financially, it has not focused on gender equality, making it more difficult for women to be able to pursue their chosen careers. Japanese women have greater access to higher education than ever before, yet the Japanese patriarchal social structure still compels women to rely on men and all but eliminates their independence. The Japanese male-dominated society is resistant want to change. Family ties are still very strong, and women are expected to take care of the household and do unpaid work, while men work outside the home and earn a paid salary. In the labour force, women do not enjoy the same level of equality and opportunity as their male counterparts, as it is naturally marry, have children, and take care of the family. The system is skewed in favor of the males. Women are not able to pursue the same career path as men; even from the start, women are often considered as candidates for potential wives for the male workers. In the course of this research, I conducted a total of 22 interviews of single and married Japanese women. -

Disability and Deafness, in the Context of Religion, Spirituality, Belief And

Miles, M. 2007-07. “Disability and Deafness, in the context of Religion, Spirituality, Belief and Morality, in Middle Eastern, South Asian and East Asian Histories and Cultures: annotated bibliography.” Internet publication URLs: http://www.independentliving.org/docs7/miles200707.html and http://www.independentliving.org/docs7/miles200707.pdf The bibliography introduces and annotates materials pertinent to disability, mental disorders and deafness, in the context of religious belief and practice in the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia. Disability and Deafness, in the context of Religion, Spirituality, Belief and Morality, in Middle Eastern, South Asian and East Asian Histories and Cultures: annotated bibliography. Original version was published in the Journal of Religion, Disability & Health (2002) vol. 6 (2/3) pp. 149-204; with a supplement in the same journal (2007) vol. 11 (2) 53-111, from Haworth Pastoral Press, http://www.HaworthPress.com. The present Version 3.00 is further revised and extended, in July 2007. Compiled and annotated by M. Miles ABSTRACT. The bibliography lists and annotates modern and historical materials in translation, sometimes with commentary, relevant to disability, mental disorders and deafness, in the context of religious belief and practice in the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia, together with secondary literature. KEYWORDS. Bibliography, disabled, deaf, blind, mental, religion, spirituality, history, law, ethics, morality, East Asia, South Asia, Middle East, Muslim, Jewish, Zoroastrian, Hindu, Jain, Sikh, Buddhist, Confucian, Daoist (Taoist). CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTORY NOTES 2. MIDDLE EAST & SOUTH ASIA 3. EAST (& SOUTH EAST) ASIA 1. INTRODUCTORY NOTES The bibliography is in two parts (a few items appear in both): MIDDLE EAST & SOUTH ASIA [c.