Transport Strategy Review: Context and Way Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Corridor Evidence Base

Transport Strategy for the South East ___ Strategic Corridor Evidence Base Client: Transport for the South East 10 December 2019 Our ref: 234337 Contents Page 4 Introduction 4 Definitions 5 Sources and Presentation 6 Strategic Corridor maps Appendices SE South East Radial Corridors SC South Central Radial Corridors SW South West Radial Corridors IO Inner Orbital Corridors OO Outer Orbital Corridors 3 | 10 December 2019 Strategic Corridor Evidence Base Introduction Introduction Definitions Table 1 | Strategic Corridor definitions 1 This document presents the evidence base 5 There are 23 Strategic Corridors in South East Area Ref Corridor Name M2/A2/Chatham Main Line underpinning the case for investment in the South England. These corridors were identified by SE1 (Dartford – Dover) East’s Strategic Corridors. It has been prepared for Transport for the South East, its Constituent A299/Chatham Main Line SE2 Transport for the South East (TfSE) – the emerging Authorities, and other stakeholders involved in the South (Faversham – Ramsgate) East M20/A20/High Speed 1/South Eastern Main Line SE3 Sub-National Transport Body for South East England development of the Economic Connectivity Review. (Dover – Sidcup) A21/Hastings Line – in support of its development of a Transport Since this review was published, the corridors have SE5 (Hastings – Sevenoaks) A22/A264/Oxted Line Strategy for South East England. been grouped into five areas. Some of the definitions SC1 (Crawley – Eastbourne) and names of some corridors cited in the Economic South M23/A23/Brighton -

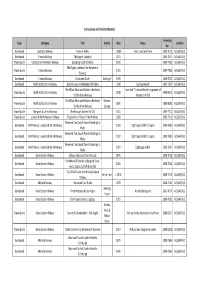

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

New £1.8M Footbridge Opens at Eridge Station in East Sussex

The new footbridge at Eridge station Oct 30, 2020 17:30 GMT New £1.8m footbridge opens at Eridge station in East Sussex Network Rail have issued the following press release: Passengers will now benefit from improved access at Eridge station in East Sussex after the opening of a new £1.8m footbridge. The work was needed due to the age and condition of the old structure, in order to protect the safety of those using the bridge and the trains operating below. Eridge station serves the rural district in East Sussex with Southern trains services via the Uckfield branch of the Oxted line. The existing staircases and bridge have been replaced with a new modern-designed footbridge. Glazing panels have been incorporated into the footbridge to allow for natural light. The platform canopies at Eridge station have also been refurbished, improving the overall passenger experience for passengers commuting to London or visiting the Spa Valley Railway. Paul Harwood, regional investment director for Network Rail, said: “I’m very grateful to passengers for their patience whilst we improved the footbridge at Eridge station. The new bridge will deliver a safe and reliable walking route over the railway while maintaining access between the lineside communities. “We are committed to improving the railway environment for passengers, and this footbridge will enhance their journey experience for many years to come”. Chris Fowler, Customer Services Director for Southern and Gatwick Express, said: “On behalf of our Eridge customers, we welcome Network Rail’s major investment in modern safety and comfort standards. “The new footbridge will complement the comprehensive refurbishment in the pipeline for Eridge station, including improvements to the main building, better seating and toilets, as part of our network-wide, multimillion-pound station improvement programme. -

Background Information for the Transport Committee's Meeting on 7 March on Crossrail and the Future for Rail in London

Background information for the Transport Committee’s meeting on 7 March on Crossrail and the future for rail in London This document contains written submissions received for the Transport Committee’s review of Crossrail and the future for rail in London. Contents: Page number: Submissions received from stakeholders: 1. Crossrail 1 2. Network Rail 23 3. Travelwatch 28 4. ORR 35 5. RailFreight 37 6. TfL response to NR business plan 39 Submissions received from rail user groups and members of the public: 7. London Forum of Civic & Amenity Societies 47 8. Brent Council 49 9. Graham Larkbey 50 10. Clapham Transport User Group Submission 50 11. Simon Fisher 62 12. West London Line Group 64 13. James Ayles 67 12. East Surrey Transport Committee 69 Report for the London Assembly Transport Committee Document Number: CR-XRL-Z-RGN-CR001-50004 Document History: Version: Date: Prepared by: Checked by: Authorised by: Reason for Revision: For issue to the London Andrew 1.0 27-02-13 Luke Jouanides Sarah Johnson Assembly Transport Wolstenholme Committee This document contains proprietary information. No part of this document may be reproduced without prior written consent from the chief executive of Crossrail Ltd. Page 1 of 22 © Crossrail Limited 1 Document Title Document Number CR-XRL-Z-RGN-CR001-50004 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 2 Delivery: progress, scope, risk and schedule ........................................................ 3 2.1 Progress -

The Development of Railways Around Ashdown Forest 1850-1914

The Development of Railways around Ashdown Forest 1850-1914 A collation of text and images from the Group’s exhibition Ashdown Forest in a Time of Change, 1850-1914 which was held at the Ashdown Forest Centre from 5 July to 31 August 2017 Martin Berry 1 Contents 1. Preface 3 2. Overview 4 3. East Grinstead 9 4. Royal Tunbridge Wells 13 5. The Upper Medway Valley 15 6. Uckfield 17 7. Crowborough 18 8. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle 23 9. The Impact of Local Railways 25 2 Preface In July and August 2017 the Ashdown Forest Research Group held its second exhibition at the Ashdown Forest Centre, Wych Cross. Entitled “Ashdown Forest at a Time of Change: 1850-1914”, the exhibition covered a diverse range of topics that illustrated some of the profound changes that were taking place to the Forest and its communities in the period from the middle of the 19th century through to the outbreak of the First World War. We have now collated the text and images from the exhibition into a series of booklets based around these topics. They comprise: 1. Ashdown Forest at a Time of Change: A Timeline 2. Aspects of Change in Forest Occupations 3. Life and Leisure on the Forest 4. Changing Architectural Styles on the Forest Edge 5. The Development of Railways around Ashdown Forest These booklets are being made available for download as PDFs from the website of the Conservators of Ashdown Forest – the address is on the back page. If you wish to contact the authors of any of these booklets, please get in touch via the group’s email address – also given on the back page. -

London to Oxted, East Grinstead, & Beyond in the Days of Steam Information on the Oxted Line

London to Oxted, East Grinstead, & Beyond in the Days of Steam Information on the Oxted Line: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Oxted_Line http://zoom.it/PvLM 30 September 1948: London Bridge (Central) Station, with Oxted line train leaving, view NW, towards buffer-stops of the Central Section (ex- LB&SCR) terminus. The locomotive is LB&SCR L.B. Billinton J2 class 4-6-2T No. 32326 (built 3/12 as No. 326 'Bessborough', withdrawn 6/51)—a rather splendid rarety. By Ben Brooksbank Southern Railway Films video of Oxted line in steam days, part 2, showing class 4 tanks at work on the line: http://youtu.be/LWDyuX01DAA http://zoom.it/5LCp 7 June 1954: Victoria (Central)-East Grinstead. View towards buffer-stops on Platform 14, Victoria Central (ex-LB&SC) Station. The 12.03 to Brighton via Oxted and East Grinstead is headed by BR Standard 4MT 2-6-4T No. 80085, which was then brand-new from Brighton Works and allocated to Bletchley LMR. It soon returned to the SR on which it worked until withdrawal in 7/67. (At the next platform is the Pullman 'Brighton Belle' By Ben Brooksbank http://zoom.it/Seeh 22 March 1957: Oxted line train from Victoria leaving Clapham Junction View NW from Strathblaine Terrace bridge, towards Clapham Junction station: ex-LB&SC main line from Victoria. The 14.08 Victoria - Tunbridge Wells West via Oxted is headed by LMS-type Fairburn 4MT 2-6-4T No. 42068 (built 10/50, withdrawn 12/63). The ex-LSW lines from Waterloo are on the right. -

Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016

TAN_308206 FC Spread_spine.qxd 1/12/14 15:07 Page 1 TANDRIDGE TANDRIDGE Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016 Official Guide & Street TANDRIDGE Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016 TAN_308206 FC Spread_spine.qxd 1/12/14 15:07 Page 2 HOUSE PLANS DRAWN for your NEW BUILD EXTENSION, ROOF ROOM ANNEX, KITCHEN, EXTENSION, GARDEN STUDIO WHY MOVE WHEN YOU CAN CREATE SPACE & ADD VALUE TO YOUR EXISTING PROPERTY? We are a local architect practice based in Warlingham and provide design and planning services to obtain planning permission for domestic building projects, including new builds, home extensions and garden outbuildings. TREE FELLING, FENCING Contact us for a FREE visit and consultation to discuss your project. HEDGE CUTTING & DITCHING, Bob Mewies CHARTERED ENGINEER 07767 690331 SPRAYING, Forge Cottage, 55 Farleigh Road, Warlingham, Surrey CR6 9EJ SPORTS PITCH MAINTENANCE GROUND BREAKING Architectural Design Services OVER SEEDING www.bobmewies.com HARROW AND ROLLING, SLITTING/AERATING FERTILISING Best Buyer of any vehicle from £500 - £50,000 Part Exchanging Your Car? THE COTTAGE Been offered a poor trade in price? FRYERN FARM Why not give us a try? ROOK LANE We will try to improve your trade price. CHALDON CATERHAM Fast, friendly, professional service SURREY CR3 5AA money paid, same day instant bank transfer. Tel: CATERHAM (01883) 347881 Fax: CATERHAM (01883) 347443 01883 621348 www.paulmewies.co.uk 07970 600555 Email: [email protected] Mewies Ltd I Unit 1 I 79 Farleigh Road I Warlingham I Surrey CR6 9EJ 3034537 3033881 B/308206/11/14/ADV` -

Transport Strategy for the South East

Transport Strategy for the South East Consultation Draft October 2019 ii Transport Strategy for the South East Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Transport for the South East www.steergroup.com www.transportforthesoutheast.org.uk WSP www.wsp.com Contents iii Contents iv Foreword vi Executive Summary Chapter 1 Chapter 3 Chapter 5 Context Our Vision, Goals Implementation 2 A Transport Strategy for and Priorities 92 Introduction South East England 52 Introduction 92 Priorities for interventions 4 How this Transport Strategy 94 Funding and financing was developed 53 Strategic Vision, Goals and Priorities 95 Monitoring and evaluation 57 Applying the Vision, Chapter 2 98 Transport Goals and Priorities for the South East’s role Our Area 101 Next steps Chapter 4 14 Introduction 18 Key characteristics of Our Strategy the South East area 66 Introduction 28 The South East’s relationship with the rest of the UK 67 Radial journeys 71 29 The South East’s relationship Orbital and coastal journeys with London 76 Inter-urban journeys 33 Policy context 78 Local journeys 35 The South East’s 81 International gateways transport networks and freight journeys 86 Future journeys iv Transport Strategy for the South East Foreword I’m incredibly proud to present this draft transport strategy for the South East for public consultation. It sets out our partnership’s shared vision for the South East and how a better integrated and more sustainable transport network can help us achieve that together. Foreword v economy more than double over the next And we know we will need to make some thirty years, providing new jobs, new homes tough decisions about how, not if, we and new opportunities – all supported by manage demand on the busiest parts of our a modern, integrated transport network. -

Overarching CP5 Enhancements Plan

Strategic Business Plan: Definition of CP5 enhancements January 2013 Page Introduction 3 Summary 7 England & Wales CP5 enhancement programme 9 England & Wales - Committed Projects 10 England & Wales - funds to deliver specific outcomes 37 The Electric Spine 51 London and the South East 66 North East 84 London North West 94 Wales 98 Western 101 Scotland CP5 enhancement programme 112 Scotland - Committed Projects 113 Scotland - Funds to deliver specific outcomes 120 Scotland - Other Scottish projects 128 Page 3 Introduction This document provides more detail of the enhancements proposed for Control Period 5 as summarised in Network Rail’s Strategic Business Plan (SBP). Projects within this document are grouped into a number of categories: “Committed” Projects – These are projects that the England & Wales, and Scottish governments committed to providing funding for ahead of publishing their High Level Output Specifications. Funds to Deliver Specific Outcomes – Experience of using funds in CP4 has demonstrated the value of such an approach giving the industry flexibility to determine the most cost effective way to deliver outputs. The Electric Spine - A major north-south rail electrification and capability enhancement, increasing regional and national connectivity and supporting economic development by creating a high-capability 25kV electrified passenger and freight route from the South Coast via Oxford and the Midlands to South Yorkshire. Other projects (those projects “named” in the High Level Output Specifications and projects required -

SCRP Ltd Business Plan 2015 – 2022

Sussex Community Rail Partnership 2015-2022 SUSSEX COMMUNITY RAIL PARTNERSHIP THE NEXT SEVEN YEARS The current SCRP Business Plan ends in July 2015. It is therefore necessary to develop a new plan for the next 7 Years with the expectation of an extension of the current GTR franchise to 2022. Initial discussions with each of the current Partners took place in the period December 2014 to February 2015 with a view to presenting a first draft of the new Plan to a full partners (SAB) meeting at Gatwick on March 19th 2015. The outcome of that discussion and the subsequent review by the Board of SCRP Ltd on 24th April 2015 is embodied in the final plan presented to the SAB at its meeting on May 14th 2015. The Plan has four sections:- 1. Executive Summary. Page 2 2. Where we are. Page 4 3. Where we want to be. Page 12 4. How we will get there. Page 16 1 Sussex Community Rail Partnership 2015-2022 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 The Partnership, now into its second decade, is serving a very useful purpose for the Partners themselves and the communities they serve. In its second decade the availability of resources for the Partners to carry out projects they feel are advantageous to the community will remain a constant challenge. The Partnership has some core funding guaranteed by Govia Thameslink railway (GTR) and Gatwick Airport for up to seven years. This leaves funding still to be found for projects. SCRP can look to generate funding through consultancy and development work for other organisations. -

CP5 Enhancements Delivery Plan

CP5 Enhancements Delivery Plan June 2015 Contents – Introduction 3 – Changes to the plan 9 – List of Projects Rolled from CP4 10 – Summary 11 – England and Wales CP5 enhancement programme – England and Wales – funds 13 – England and Wales – projects – Cross route projects 38 – Electric spine 52 – Anglia 59 – Kent 68 – Sussex 75 – Wessex 77 – Western 92 – Wales 110 – LNE 113 – East Midlands 127 – LNW 130 – Scotland CP5 enhancement programme – Scotland – funds 141 – Scotland – projects 147 CP5 Enhancements Delivery Plan Introduction Purpose The CP5 Enhancements Delivery Plan sets out the outputs, scope and milestones that we are committed to deliver in CP5. It has an entry for every project and ring-fenced fund funded through PR13. It is used both by the regulator, to hold us to account, and by our customers and funders, to give them visibility of our plans. As well as describing our commitments through the periodic review, it also sets out the deliverables for other government sponsored enhancement schemes funded through the Investment Framework. The Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) published the Final Determination on 31 October 2013. Network Rail accepted the Final Determination on 7 February 2014. This document is part of Network Rail’s response to the Final Determination. We have continued to develop our plans for Control Period 5. As we have refined our plans, elements have changed and we set out the changes from the draft plan in the ‘changes to the plan’ chapter later in the document. Change control and updates This document will be updated on a quarterly basis to report progress and to update projects where appropriate. -

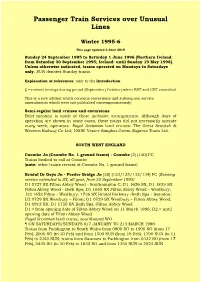

Passenger Train Services Over Unusual Lines

Passenger Train Services over Unusual Lines Winter 1995-6 This page updated 2 June 2015 Sunday 24 September 1995 to Saturday 1 June 1996 [Northern Ireland: from Saturday 30 September 1995; Ireland: until Sunday 19 May 1996]. Unless otherwise indicated, trains operated on Mondays to Saturdays only. SUN denotes Sunday trains. Explanation of references: refer to the Introduction § = revised timings during period (September/October) when BST and CET coincided This is a new edition which contains corrections and subsequent service amendments which were not published contemporaneously. Semi-regular land cruises and excursions Brief mention is made of these inclusive arrangements. Although days of operation are shown in some cases, these trains did not necessarily operate every week; operators: Royal Scotsman land cruises: The Great Scottish & Western Railway Co Ltd; VSOE: Venice Simplon-Orient-Express Tours Ltd. SOUTH WEST ENGLAND Coombe Jn (Coombe No. 1 ground frame) - Coombe [2] (140) PC Trains booked to call at Coombe [note: other trains reverse at Coombe No. 1 ground frame] Bristol Dr Days Jn - Feeder Bridge Jn [28] (123/125/132/134) PC {Existing service extended to SX, all year, from 25 September 1995} D1 0727 SX Filton Abbey Wood - Southampton C; D1 1626 SX, D1 1835 SX Filton Abbey Wood - Bath Spa; D1 1655 SX Filton Abbey Wood – Westbury; D2 1652 Filton - Westbury; 1736 SX Bristol Parkway -Bath Spa - Swindon; D2 0729 SX Westbury – Filton; D1 0729 SX Westbury – Filton Abbey Wood; D1 0912 SX, D1 1750 SX Bath Spa -Filton Abbey Wood D1 =