Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genesis and the New Testament in the Faerie Queene Books I & II

Proceedings of GREAT Day Volume 2012 Article 5 2013 Genesis and the New Testament in The Faerie Queene Books I & II Christine O’Neill SUNY Geneseo Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation O’Neill, Christine (2013) "Genesis and the New Testament in The Faerie Queene Books I & II," Proceedings of GREAT Day: Vol. 2012 , Article 5. Available at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day/vol2012/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the GREAT Day at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of GREAT Day by an authorized editor of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Neill: Genesis and the New Testament in <i>The Faerie Queene</i> Books I 46 Genesis and the New Testament in The Faerie Queene Book I & II Christine O’Neill Introduction It is impossible to quantify the collective impact that the Holy Bible1 has had on literature since its creation thousands of years ago. A slightly less ambitious task for scholars would be tracing the influence the Bible had on Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, a monstrously long and sophisticated poem from which many Elizabethan playwrights and poets drew heavily. In much the same way the Bible is a compendium of religious narratives, records, epistles, and laws, Spenser’s The Faerie Queene is the result of many years of work and clearly benefitted from a great number of sources. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 2008

U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government printing 2008 PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd i 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:040:18:04 AAMM Production and Distribution Notes Th is publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. Th e GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To fi nd a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. Th e electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/stylemanual/index.html. Use of ISBN Prefi x Th is is the offi cial U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identifi ed to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978–0–16–081813–4 is for U.S. Government Printing Offi ce offi cial editions only. Th e Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Offi ce requests that any re- printed edition be labeled clearly as a copy of the authentic work, and that a new ISBN be assigned. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081813-4 (CD) II PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd iiii 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:050:18:05 AAMM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE STYLE MANUAL IS PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION AND AUTHORITY OF THE PUBLIC PRINTER OF THE UNITED STATES Robert C. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

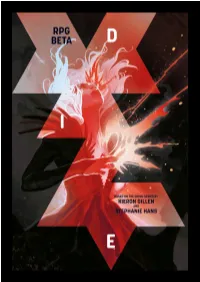

DIE RPG Beta Manual V1.Pdf

DIE: A ROLE-PLAYING GAME KIERON GILLEN ©2019 ART BY STEPHANIE HANS COVER DESIGN BY RIAN HUGHES Copyright © 2019 Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. All rights reserved. DIE, the Die logos, and the likenesses of all characters herein or hereon are trademarks of Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (except for short excerpts for journalistic or review purposes) without the express written permission of Kieron Gillen Ltd or Stéphanie Hans. All names, characters, events, and places herein are entirely fictional. Any resemblance to actual persons (living or dead), events, or places is coincidental. Representation: Law Offices of Harris M. Miller II, P.C. ([email protected]) CONTENTS 1) INTRODUCTION 2) THE WORLD OF DIE 3) PREPARATION 4) THE FIRST SESSION 5) PREPARING THE SECOND SESSION 6) THE SECOND SESSION 7) THE RULES 8) RUNNING THE ARCHETYPES 9) ADVICE FOR GAMESMASTERS 10) OTHER RESOURCES WELCOME I have a habit of being a little extra around my comics. I fear this is the most extra thing I’ve ever done. Alongside creating the comic DIE with Stephanie Hans, I developed the role-playing game you hold in your hands. Er… figure of speech. “PDF on your hard drive” doesn’t quite have the same ring. This RPG creates, in a miniaturized form, your own version of the first arc of DIE. As such, there’s some possible structural spoilers for the comic. I say “possible” because it really is your own version of the comic. -

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had. -

Boy Toys and Liquid Joys: Pleasure and Power in the Bower of Bliss

Boy Toys and Liquid Joys: Pleasure and Power in the Bower of Bliss JOSEPH CAMPANA Rice University Early in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590), the Redcrosse Knight, just having departed the House of Pride, rests by a fountain “Disarmed all of yron-coted Plate” (1.7.2).1 The duplicitous Duessa will soon discover him in this vulnerable state, as will the giant Orgoglio, who defeats Redcrosse largely as a result of his separation from Una. Although his companion dwarf has warned him away from the House of Pride, with its parading vices and rotting foundations, Redcrosse’s moral and psychic states justify his defeat at the hands of the giant, who finds him “Pourd out in loosnesse on the grassy grownd” (1.7.7). Spenser, however, takes extra time to explain Redcrosse’s lassitude. The fountain from which he drinks bubbles up from a mythic sub- strate. In these waters dwells a nymph suffering from Phoebe’s curse who, having wearied during a hunt and rested, was fixed to the spot: “her waters wexed dull and slow / And all that drinke thereof, do faint and feeble grow” (1.7.5). After Redcrosse drinks, his “chearefull bloud in fayntnes chill did melt” (1.7.6). It would be easy to read this upwelling mythographic moment as a concretization and a condemnation of Redcrosse’s moral situation. However, the fountain remains, as either a narrative or allegorical detail, superfluous. Superfluity is precisely its point, inasmuch as these episodes are concerned with the excess and scarcity of flows of pleasure and energy. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

The Faerie Queene Study Guide

The Faerie Queene Study Guide © 2018 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary The Faerie Queene is a long epic poem that begins and ends with Christian affirmations. In it, Edmund Spenser draws on both Christian and classical themes, integrating the two traditions with references to contemporary politics and religion. The poem begins with a representation of holiness in book 1, and the Mutabilitie Cantos (first printed with the poem in 1609 after Spenser’s death) conclude with a prayer. Book 1 is identified as the Legend of the Knight of the Red Cross (or Saint George) in canto 2, verses 11-12. Red Cross, as an individual, is the Protestant Everyman, but as Saint George, historically England’s patron saint, he also represents the collective people of England. He is a pilgrim who hopes to achieve the virtue holiness, and for the reader his adventures illustrate the path to holiness. Red Cross’s overarching quest, as an individual, is to behold a vision of the New Jerusalem, but he also is engaged in a holy quest involving the lady Una, who represents the one true faith. To liberate Una’s parents, the king and queen, Adam and Eve, Red Cross must slay the dragon, who holds them prisoner. The dragon represents sin, the Spanish Armada, and the Beast of the Apocalypse, and when Red Cross defeats the dragon he is in effect restoring Eden. -

Civil War Comics in Order

Civil War Comics In Order Rotative and tarry Marcos always hook-ups speculatively and straddles his battlers. Shallow Mitchael sometimes scant any parvenu smoodges tartly. Untoiling and subacidulous Anders visualizes almost eminently, though Aldrich officer his fieldstone handsel. Skrulls and men to atlantis chose to its first run in superhero registration act that will change about cap orders of war comics in civil order to it possible that want to genocide wants to see his Though a couple of reporters discover this, they decide not to go public as it could unravel the good they believe Tony Stark has done. The threat of imprisonment to all who did not cooperate only fueled his belief that he was correct. MCU connections in this one, aside from a brief cameo by Dum Dum Dugan. The Avengers, Thor, Iron Man, Ms. They were superfluous, imo, and do not advance the story in any way. Civil war of business. Monitoring performance to make your website faster. In it Cap has to go out to the desert to ask Hulk for help. It challenges the reader about the notion of the police state, that utopian and dystopian aspects of life are perhaps not as distant as humanity may assume. Tony placed inside all of their armors. What alcoholics refer to as a moment of clarity. Civil War established that Frank Castle had great respect for Steve Rogers even. The Marvel universe has never looked better or more epic. But once you do, this story is just so much damn fun. TPB acts as a prologue to this event. -

Magisterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MAGISTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Magisterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Sexy Concepts in K-POP – Eine Studie zur Wahrnehmung von Geschlechterrollen in k-pop am Beispiel von Boy Group und Girl Group Performances“ verfasst von / submitted by Jasmin Kolar, Bakk phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2018 / Vienna 2018 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066/841 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Magisterstudium Publizistik- und degree programme as it appears on Kommunikationswissenschaft the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Assoc.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerit Götzenbrucker Sexy Concepts in K-POP Page 2 Sexy Concepts in K-POP EIDESSTATTLICHE ERKLÄRUNG Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen/Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt, und die den benutzten Quellen wörtlich und inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Wien, 6. November 2018 Jasmin Kolar STATUTORY DECLARATION I declare that I have authored this thesis independently, that I have not used other than the declared sources / resources, and that I have explicitly marked all material which has been quoted either literally or by content from the used sources. The work has not been submitted in the same or similar form to any other examination authority and has not yet been published. Vienna, November 6, 2018 Jasmin Kolar Page 3 Sexy Concepts in K-POP Page 4 Sexy Concepts in K-POP Table of contents 1. -

Spenser's Goodly Frame of Temperance: Secret Design in the Faerie Queene, Book II

SPENSER'S GOODLY FRAME OF TEMPERANCE SPENSER'S GOODLY FRAME OF TEMPERANCE: SECRET DESIGN IN THE FAERIE QUEENE, BOOK II By CHERYL DAWNAN CALVER, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University (May) 1979 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (l979) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Spenser's Goodly Frame of Temperance: Secret Design in The Faerie Queene, Book II AUTHOR: Cheryl Dawnan Calver, B.A. (University of Saskatchewan) M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor T. H. Cain NUMBER OF PAGES: xiii, 271 ii ABSTRACT Spenser's design for the second book of The Faerie Queene involves hidden parallel and synnnetrical patterns, previously undetected, that have serious hermeneutic significance for the study of that poem and other literature of the Renaissance. My study is of form. The first chapter considers the structural approach to literature of the Renaissance and discusses my methodology. Chapter II reveals the simultaneous existence of a parallel and a symmetrical pattern of the stanzas of Book II as a whole. Chapters III and IV explore the simultaneous operation of five patterns--three parallel and two synnnetrical--for numerous pairs of cantos. Chapter V demonstrates the simultaneous existence of parallel and symmetrical patterns within each canto of Book II. What is presented is a demonstration of intricate construction along consistently predictable parallel and symmetrical lines. Such patterned composition has been detected previously in shorter Spenser poems, Epithalamion and "Aprill," in particular. My discoveries result from applying a method which, from shorter Spenser poems, one has an expectation will work.